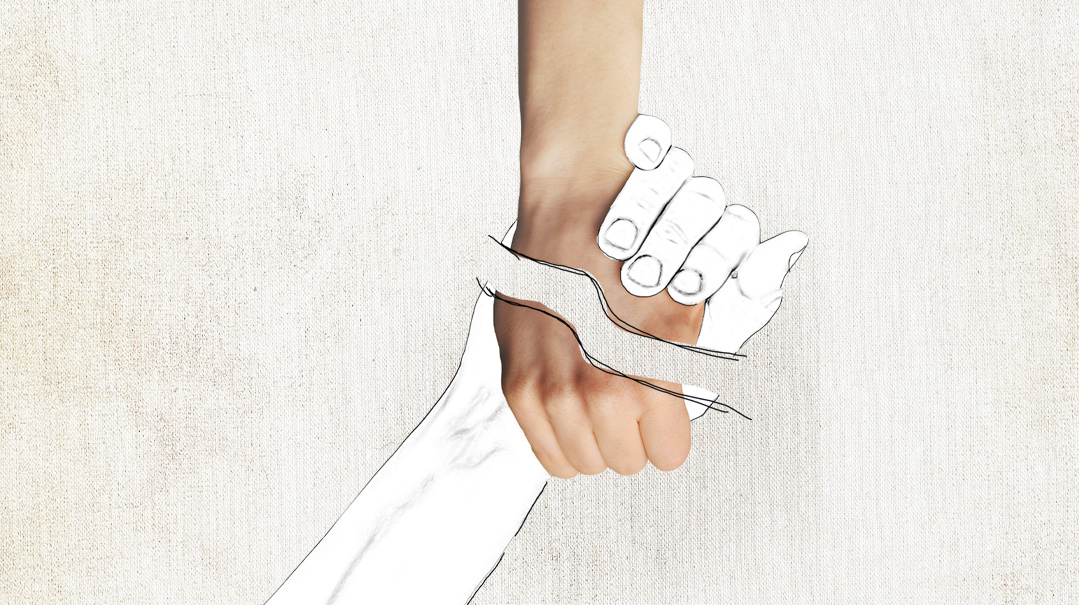

Split Loyalties

| July 26, 2022Was this my perky daughter and her exuberant chassan? What was happening between them? Was everything okay?

Devora: I’m willing to do everything possible to help my daughter. Why won’t you share what’s going on?

Ayala: My primary obligation is to your daughter — and right now that means respecting her privacy.

Devora

Miri wasn’t answering her phone. Again.

Calm down, I told myself. It’s probably nothing. She’d only been married a few weeks, after all, and I knew only too well what the all-encompassing intensity of shanah rishonah could be like.

But still, something felt a little… off. Miri was my oldest daughter and we were pretty close. I would’ve expected her to call me back within a day or two, or at least send a quick text. I’d invited the couple for Shabbos, but it was already Thursday and I hadn’t heard back from them. Miri was a bubbly social butterfly, and she loved schmoozing on the phone. What was going on?

Navigating a new marriage isn’t easy. Give her space, I told myself, but I couldn’t help but worry a little. Was Miri okay? Was anything wrong?

On Friday, Miri finally texted that they’d be coming for Shabbos, sorry she forgot to reply earlier. Oookay. I threw together a couple of extra side dishes — luckily I’d prepared a roast in addition to the chicken, on the chance that the couple would be joining us — and asked my younger daughter Estee to run and buy some more desserts. Preparing the guest room at the last minute was a little inconvenient, but honestly, I was just relieved she’d be coming, and I would get to see her for myself, check if everything looked okay.

M

iri and Shmuli arrived a half hour before Shabbos. Miri looked picture-perfect in her Shabbos sheva brachos dress and flawless makeup, kallah jewelery sparkling. But something looked… a little off. Had she lost weight?

“Come inside, come take something to eat,” I said, trying to mask my worry as I passed out plates of kugel and cake.

Miri thanked me quietly and Shmuli gave a half-hearted nod. They both perked up after eating something; I guess fresh kugel will do that to anyone. But… was this my perky daughter and her exuberant chassan? What was happening between them? Was everything okay?

Oops! We could not locate your form.