Mesorah of Miracles

“How could any yeshivah turn away a bochur with a smile like yours?”

He pressed his talmidim to work harder, learn longer, to push themselves and never give up. It’s been five years since the passing of Rosh Yeshivah Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel ztz”l, but could the 8,000-strong army he created still march forward? Yet that striving for growth and determination against the odds is his enduring legacy, his indomitable spirit alive in every corner

O

n Monday evening, 11 Cheshvan 2011, the Rosh Yeshivah was on a conference call, discussing plans for an upcoming fundraising trip to the United States.

After he hung up, he welcomed some talmidim into his dining room. This was also the living room and study and unofficial office, the place where he met new bochurim, delivered chaburos and shmuessen, led administrative meetings. Most of all, it was where he learned, and on that evening, bochurim came to speak in learning as well.

He wasn’t feeling great, but it had been many years since he’d felt well. He pushed off exhaustion and made another phone call, reaching then Shas leader Eli Yishai. The Rosh Yeshivah thanked him for accommodating the request of various roshei kollel to arrange a discount on the municipal property tax for avreichim. “It’s a tremendous load off my heart,” Rav Nosson Tzvi told him.

The Rosh Yeshivah went to sleep.

On his schedule for early the next morning was another conference call with the yeshivah’s American administrative staff. But it was delayed.

Word filtered down that something was amiss, that the Rosh Yeshivah wasn’t well.

Hatzolah members filled the house on Rechov Ha’Amelim. There was nothing they could do.

Across the American night, sleep was shattered as the news was appropriate for those darkest hours before dawn. Would the sun rise on a world without Rav Nosson Tzvi?

* * * * *

The Yeshiva had faced challenge before.

For two centuries of our People’s sojourn through galus, the sound of Torah in the Mirrer beis medrash has been heard, the soundtrack to so much of our history. Founded in Mir, Poland, in 1817, its talmidim learned through war and hunger; when the Nazi beast forced them to flee Poland, the gemaras went too. The Mir would rise, on eagles’ wings, its heart and soul transported to the ends of the world — they would find respite in distant Shanghai, where the yeshivah flourished during the early part of the 1940s.

Eventually, the Mir landed in Eretz Yisrael, where Rav Eliezer Yehuda Finkel, a son-in-law of the previous rosh yeshivah and rav of Mir — Rav Eliyahu Boruch Kammai, restored it to its former glory. His son, Rav Beinish, assumed the position of rosh yeshivah and with it, the daunting task of fundraising for the burgeoning institution.

Then he took ill, and all kinds of questions arose. Who were his secret sources for funding the yeshivah? And what would happen when he was gone?

Days before his passing, Reb Beinish looked at the concerned faces of family members gathered around his bed. “I know that you all expect to hear something from me,” he said, “but the truth is, ich veis alein nit, I also don’t know the answer.”

The succession was carried out in characteristically understated fashion. The yeshivah’s secretary made his way to the hospital and asked Rav Beinish whose name should go on the amutah, the official nonprofit entity, in place of Rav Beinish. “My son-in-law, Rav Nosson,” was the reply, the very informal coronation of a new king.

* * * * *

There were doubters, at first.

He was young, in his forties, with little leadership experience.

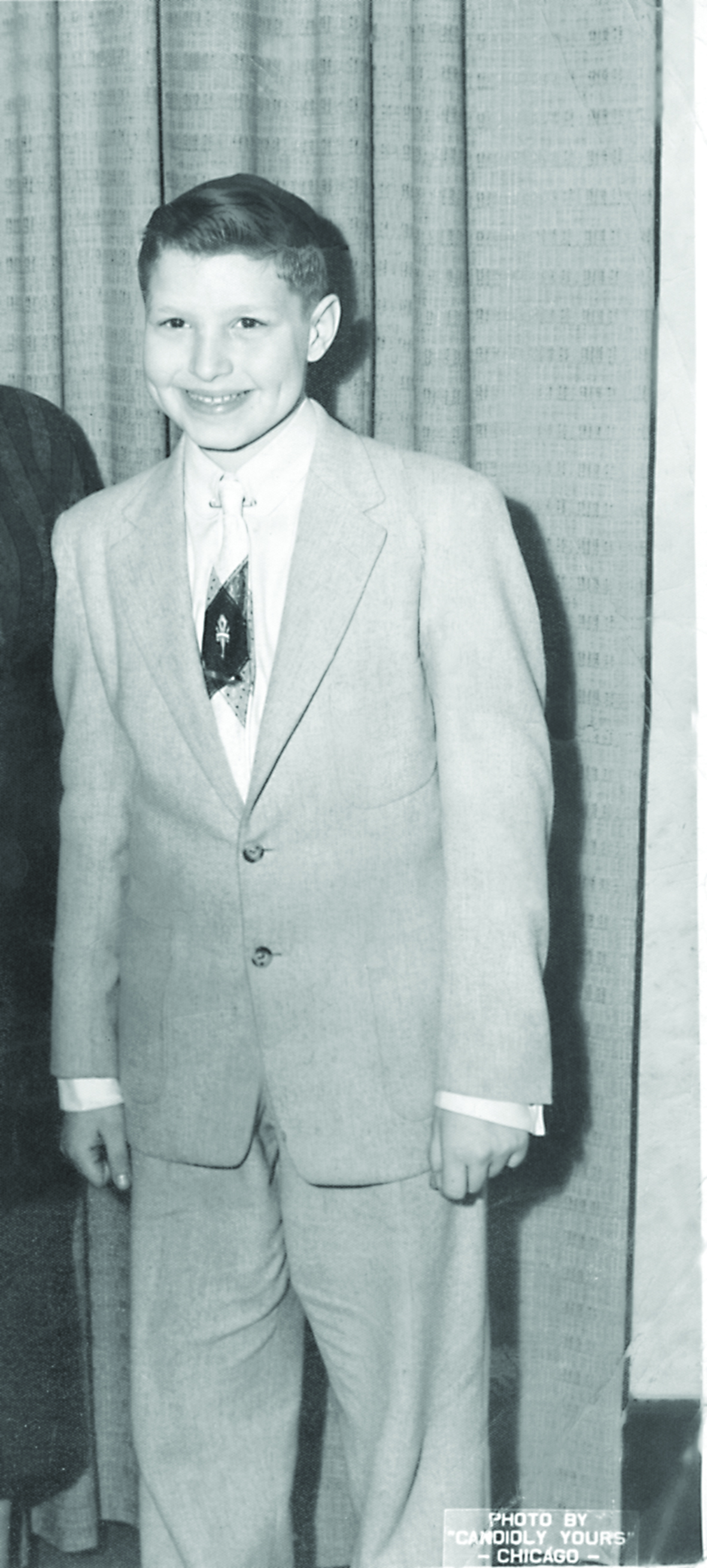

He was American, a product of Chicago, raised with baseball and hot dogs, a world away from the narrow alleyways of Beis Yisrael.

He was already ill, having been diagnosed with the Parkinson’s that would make every moment a battle.

But he had the spirit.

A few months later, Rav Refoel Shmuelevitz ( son of Rav Chaim, who’d been a son-in-law of Rav Leizer Yudel) was dancing at a yeshivah event along with the other roshei yeshivah. He contemplated the new rosh yeshivah, the young man radiating vitality and warmth, and commented in wonder, “Do you see? He’s younger than all of us, but look at him...”

Over time, Rav Nosson Tzvi’s illness would get worse; but his determination, it seemed, progressed at the same pace.

He presided over exponential growth, hundreds of talmidim becoming a thousand, then several thousand.

An American businessman visited the Mir during those years and saw the single building jammed to capacity, talmidim learning under the stairwell and in the hallway and on the platform in front of the aron kodesh.

Rav Nosson Tzvi confided to the visitor that, much as he enjoyed the unique atmosphere, the cloud of Torah that seemed to hover over the building, he wished he had more space so that he could accept additional talmidim.

The businessman asked for a piece of paper and drew 20 boxes, writing his own name in the very first box. “Rosh Yeshivah, here’s what you should do. Each of these boxes will cost $100,000. One is already taken. Now, you’ll go fill the other 19 and you’ll buy another building.”

Over the years, the rosh yeshivah would often thank his American friend — not just for the money, but for the concept. “You taught me that the best way to make things happen is to have bitachon and jump in.”

The man who would emerge as the biggest builder of Torah in modern history learned quickly. The great philanthropists were drawn in by his warmth, his sincerity, his exceptional chein: his tangible love of Torah affected them too. One building, then another, then a third.

But the Rosh Yeshivah reserved his greatest innovation and creativity for the beis medrash: he was CEO of the yeshivah’s neshamah as much as its guf.

He developed a program for talmidim to write chiddushei Torah, and motivated them to finish the yeshivah’s masechta. He challenged the notion that Erev Shabbos was a day off. He pushed talmidim to deliver their own chaburos and would personally listen as they were delivered. He demanded and prodded and always won: after all, who could say no to a man who happily defied the rules of his own body?

You Can Do It

I’ll never forget Bava Basra zeman: It was late in the winter of 1997, just about the time when the initial enthusiasm fades away, but when Pesach bein hazemanim is still a distant blip on the horizon. The Rosh Yeshivah announced an initiative — he wanted the bochurim to commit to learning 12 hours each day.

He had a special way of demanding something difficult, yet making the proposal sound pleasant nonetheless. He didn’t stop smiling as he explained that he really wasn’t asking for that much — just that the talmidim use every second of regular sedorim. He made it clear that he expected the good bochurim to sign up for this kabbalah, adding their names to a long list that had been hung up specifically for this purpose, and which he himself would be monitoring.

It was the first Friday after the Rosh Yeshivah’s announcement: The energy and spirit were felt in every corner of the yeshivah, with bochurim sitting in their places and learning — no chatting, no airing out — from nine in the morning until midnight, with only the necessary breaks.

The usual crowd filled the Rosh Yeshivah’s dining room for the weekly Erev Shabbos shmuess, and after Rav Nosson Tzvi was done, the bochurim filed by to wish him a gut Shabbos. This was a special moment, week after week, for the attendees — a cherished personal moment for each talmid.

The Rosh Yeshivah stopped a particular talmid, a bochur I personally knew well. “I didn’t see your name on that list.”

The bochur was stunned. He wasn’t the type — 12 hours wasn’t in his stretch zone: full sedorim were enough of a challenge.

He laughed, hoping that the Rosh Yeshivah would let him move on.

“I want you to join,” said the Rosh Yeshivah, his face suddenly very serious.

“I can’t. Don’t worry, there are enough other bochurim doing it.”

The Rosh Yeshivah didn’t let go. “Do you have a pen? Let’s do it.”

And so he signed.

The talmid, with no recourse, pushed himself through one seder, then another. At the end of the first day, he tasted exhaustion unlike anything he’d ever experienced. The next day was a test of endurance, as he fought on, determined to honor his pledge.

A few days in, he came to his dirah at the end of a long day, feeling the thrill and fatigue overtake him at once, and he fell into a deep sleep.

His dreams carried with them hints and echoes of the words he’d spoken throughout the preceding day: Chardal, Rashi’s shittah, Reb Nochum’s diyuk…He awoke in the morning suffused with an extraordinary joy, and could barely contain himself through Shacharis.

As soon as davening was over, he hurried across the street to the Rosh Yeshivah’s home.

“Rebbi, I dreamed in learning!”

Rav Nosson Tzvi smiled a knowing smile and rose to his feet. He reached for the hands of his talmid and together, they started to dance.

It was that kind of yeshivah too.

A Smile Like Yours

I remember him in the best years, the late ’90s. He was a recognized gadol, yet approachable and friendly as a high school rebbi in a small yeshivah. In a moment, he seemed able to size up a bochur’s needs and insecurities, to deliver the balm of a well-chosen compliment, or even just a gentle smile.

There was a bochur who came to Eretz Yisrael with plans to learn in another yeshivah, certain that he’d been accepted. When he showed up, it turned out that it had been a misunderstanding: He had no yeshivah.

He was humiliated and hurt. With no choice, he headed to Mir for the Elul zeman, hoping to clear things up with his first choice before the winter started.

He didn’t bother registering in the Mir office, and simply took a seat in the crowded beis medrash and started learning — after all, who would notice one more face in a sea of thousands?

As he sat there, he felt eyes on him. The Rosh Yeshivah himself was looking at him. The bochur hurried over to introduce himself, offering an embarrassed explanation for his presence.

Rav Nosson Tzvi listened and then spoke, his voice filled with wonder. “How could any yeshivah turn away a bochur with a smile like yours?”

The Best Deal

Rav Nosson Tzvi led the yeshivah into a new millennium. His name and reputation — an authentic American gadol who’d never forgotten his background — spread well beyond the yeshivah and its orbit. The weekly English shmuess drew talmidim from many other yeshivos, plus tourists and visitors vying for a whispered brachah.

Yet with the yeshivah’s steady growth came a massive budget — and by this time the Rosh Yeshivah was weaker than ever. Still, he responded to these challenges with an ambitious new project: a branch in Kiryat Sefer, Mir-Brachfeld, which would quickly become a leading yeshivah in its own right.

It became more difficult for him to travel, yet the yeshivah’s numbers kept swelling. More subsidized bus routes for avreichim, another shift enjoying a nourishing hot lunch, more stipends and programs.

He was indomitable.

Then came 2008.

So many of the philanthropists on whom the yeshivah relied were impacted by the global financial crisis, and Rav Nosson Tzvi faced his biggest challenge yet.

He pushed himself to travel even more than usual: he was often pale and sometimes inaudible.

Two things didn’t change, though. The glowing smile, and the ability to remain immersed in learning, to go directly from the airport to deliver a shiur as if he’d been preparing in his own beis medrash. His shiurim — a unique style built on showing the consistency in various shittos in Rishonim, each one a sweeping overview of the entire masechta — were profound as ever.

On a fundraising visit to Baltimore, the Rosh Yeshivah was asked to speak at Ner Israel. It was near the end of the zeman, so Rav Nosson Tzvi issued a challenge to the talmidim similar to ones he offered in his own yeshivah: he would give a generous stipend to each yungerman who committed to learning a certain number of hours without interruption.

A young balabos who was close to the Rosh Yeshivah heard the story, but he didn’t believe it: There was no way that Rav Nosson Tzvi would offer money to talmidim of another yeshivah when his own yeshivah was so strapped for money.

He asked the Rosh Yeshivah about the story. “Yes, we’re short on money,” Rav Nosson Tzvi smiled broadly, “but it was a very good deal. I couldn’t pass it up.”

In those final years, he took the uncharacteristic step of referring to his own condition. He visited a donor at home and requested an unusually large donation. “I can’t,” said the host.

“I also can’t,” Rav Nosson Tzvi stated flatly, “but I do it anyway.”

During that time, the yeshivah was late with the kollel stipend checks. Its struggles, he believed, were due to his own failings. “I am embarrassed to look the yungeleit in the face,” he commented, “because I know that if I had true emunah, we would have money to pay everyone. If I was on my rebbetzin’s level, we wouldn’t be in this situation.”

Stay Connected

During the summer of 2011, the Rosh Yeshivah traveled to America, armed with a message, a thought he repeated at the various fundraisers he attended. Chazal list 48 ways to acquire the Torah, means of becoming a kinder, humbler, more generous person, prerequisites to true kabbalas haTorah. Why are they necessary? Because Torah belongs to all of Klal Yisrael, the Rosh Yeshivah explained, and the more one becomes part of the klal, the more he’s connected with the Torah.

It would be his farewell from the thousands of talmidim and supporters he met over the course of that trip, which created a sensation of achdus, middos, and Torah.

It was a tense Elul. A sense of despair spread across the yeshivah world as government cutbacks grew more severe. It wasn’t just the money — it was the negative portrayal of bnei yeshivah, the sense that avreichim were “takers.” It was a hard time to be a proud avreich and Rav Nosson Tzvi, whose favorite song was “Ashrei Mi She’amalo baTorah,” found the new reserves of energy needed to remind them how fortunate they were, what each word of Torah can accomplish.

On Rosh Hashanah, he stood up before tekios. His eyes swept the room, an ocean of talmidim from wall to holy wall, and he spoke.

“People wonder about the proper kavanos to have during these exalted moments. Do you want to know what to think about during tekios?” He paused. “Think about each other.”

Message of Fire

Succos was always special in the Mir. The Rosh Yeshivah welcomed the usual flow of visitors from abroad with customary warmth. Over that Succos, the Rosh Yeshivah instructed his eldest son, Rav Eliezer Yehuda — who’d been delivering a popular daily shiur and had stood in for his father in distributing the kollel checks — to start wearing a frock during the upcoming zeman.

On Hoshana Rabba, he maintained a sacred minhag: sitting down in the succah and learning late into the night with his first cousin Rav Aryeh Finkel ztz”l, the Rosh Yeshivah of Mir-Brachfeld and, yblcht”a, Rav Aryeh’s son Rav Binyomin. Together, they would joyously begin the new masechta in advance of the winter zeman.

On Rosh Chodesh Cheshvan, an incoming talmid noticed a printout on the Rosh Yeshivah’s table listing all the talmidim in Mir and its institutions: close to 8,000 names, ten times more than he’d started out with.

The Rosh Yeshivah ushered in the zeman with a shmuess, exhorting talmidim to use the long winter to master the mesechta and to chazer it.

For ten days, his heart beat along with theirs. Ten precious days of a winter zeman.

And then his heart stopped.

A sign went up that Tuesday morning, the first official announcement by the yeshivah.

“Sedorim will be held as usual until the time for the levayah,” it read.

An ordinary white sheet of paper, carrying a message of fire.

At the levayah, the entire Beis Yisrael neighborhood was transformed into a house of mourning. Rav Aharon Leib Steinman announced a successor: Rav Leizer Yudel, the Rosh Yeshivah’s eldest son.

Quiet, humble, yet so dignified, another chain in a link of royalty.

On the Thursday morning following the shivah, Reb Yechiel Silberberg, the yeshivah’s veteran baal korei, asked the regular gabbai if he might replace him in calling up the people to the Torah.

Before shlishi, he squared in shoulders and, in a resonant voice, he called out “Yaamod moreinu Rav Eliezer Yehuda ben moreinu Rav Nosson Tzvi.”

Fifty years earlier, he explained, he’d been the regular gabbai when the yeshivah opened in Beis Yisrael and he had called up the first Rav Leizer Yudel by the very same name: He wished to announce it just once more. Nostalgia, perhaps, but also a resounding statement about the future.

Safeguarded Legacy

What happened next, says a hanhalah member, was pure Mir.

It was as if all of Rav Nosson Tzvi’s life’s work, the messages he’d repeated again and again — achdus, neisah be’ol, concern for another, and of course, Torah itself — came together to safeguard his legacy.

The hanhalah members gathered around the new Rosh Yeshivah just as they’d once done for his father. Rav Aryeh Finkel on his right, Rav Refoel Shmuelevitz on his left, his uncles and cousins and brothers surrounding him as he came in to deliver the first shiur klali.

A yeshivah sustained by miracles saw one more.

Rav Nosson Tzvi had left his son a glorious yeshivah, a mandate of extraordinary harbatzas Torah — and a debilitating debt.

Some three months after the petirah, a group of close friends came together to pay it off in full, donating massive amounts of money, a final gift to the Rosh Yeshivah they loved. In Shevat of that year, the avreichim of the kollel were called to the office, each one receiving a check for the full amount they were owed.

Okay, said the cynics, the Rosh Yeshivah was just niftar. Everyone wants to be a savior. But what will be next year? The year after that?

It’s five years later.

Rav Leizer Yudel has led the yeshivah into a glorious new era.

The yeshivah has more than 60 daily shiurim operating out of 25 batei medrash. Twelve thousand meals are served each day, buses converging on the yeshivah each morning from 150 directions. The siyata d’Shmaya and miracles continue, bayamim haheim, bizman hazeh.

A month ago, relates a senior hanhalah member, a yungerman approached to invite him to a siyum.

This maggid shiur was perplexed, for just a few years back, this same avreich had celebrated his own festive siyum haShas. What was this event for?

It turned out that while the first siyum was on Bavli, this was a siyum on Yerushalmi, Sifra, Sifri, Mechilta, and Midrash.

“That’s the Mir of today. We have people being mesayeim Shas who really know what they’re talking about. We have new seforim coming out of our beis medrash every few weeks. And it’s all tribute to Rav Nosson Tzvi, who inspired that kind of strength in everyone. There’s no ‘I can’t’ in his yeshivah.”

Around the world, there are memorials for the Rosh Yeshivah. Buildings and sifrei Torah and new kollelim bear his name. The yeshivah he carried on his heart is led with distinction by his son, the friends he drew close standing loyally at its side. His talmidim don’t forget, his gentle voice guiding them still, his call for greatness motivating them to learn more, to chazer one more time.

But his legacy?

He’d arrived in Mir as a teenager with a day-school education. His great-uncle, Rav Leizer Yudel, embraced him and urged him to stay. Rav Nosson Tzvi’s American parents, who hoped he’d become a doctor, acquiesced. The young boy learned with private chavrusas at the start, but with diligence and determination, he graduated, joining regular shiurim. He became a fixture on one of the back benches and he never really left: After his marriage to the Rosh Yeshivah’s daughter, he learned with the same intensity, chavrusas changing every few hours as he sat in place. The yeshivah, its schedule, its masechta, its mesorah — that became his identity.

And his story is their story. It’s about legions of young men who arrive in Mir as teenagers and never really leave, learning after marriage, growing and growing and growing on its worn benches, becoming part of what makes the Mir so extraordinary. Each of them carries a spark of Rav Nosson Tzvi, whose toil and heart would come to define the yeshivah.

“I was at a siyum haShas,” recalls a family member, “and the host was speaking. He thanked his parents and in-laws, his chavrusas. Then he thanked his wife, but he couldn’t get the words out. He started to cry — for five minutes he was crying. That’s a Mirrer yungerman. All of Shas in his heart... and there’s also room for another person. That — the gratitude, the humility, the emotion, and the entirety of Shas — that’s a talmid of the Rosh Yeshivah, of Rav Nosson Tzvi.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 634)

Oops! We could not locate your form.