Mitzvos Made Beautiful

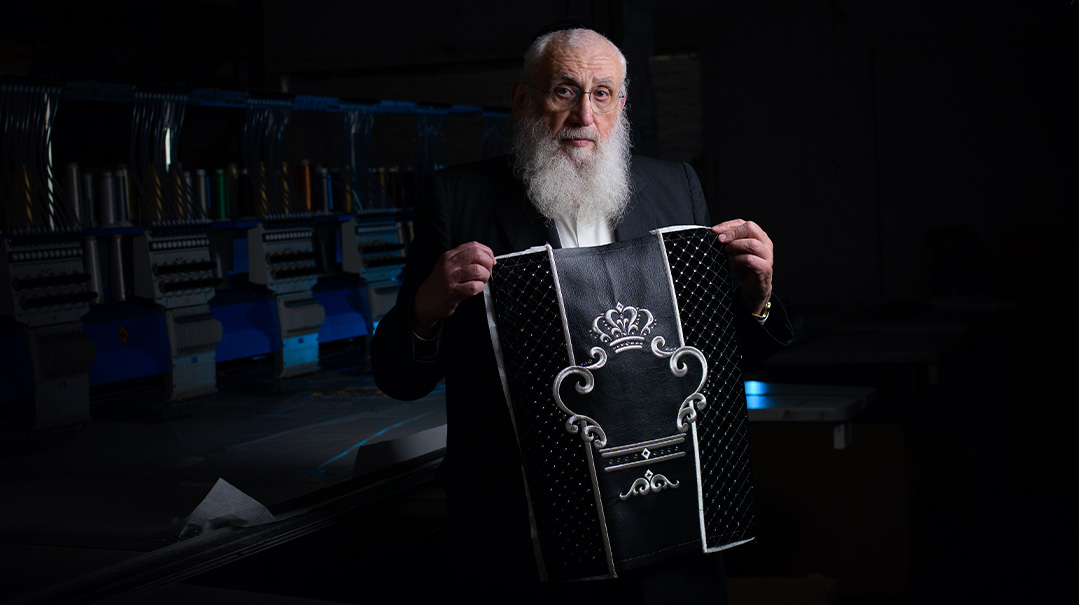

| May 31, 2022“I wanted to make these mitzvos as beautiful, as halachically acceptable, and as comfortable as possible”

Photos: Naftoli Goldgrab

IT

all started 25 years ago, when a friend convinced Rabbi Mottel Tenenbaum to go into business with him.

Rabbi Tenenbaum worked in the family nursing home business in an office building on 14th Avenue in Brooklyn, across the street from the Keter warehouse, where they manufactured sets of tzitzis, talleisim, tallis and tefillin bags, and other Judaic textile accessories. One Friday afternoon, he saw his close friend, who owned Keter, exit the warehouse looking worried. Business was grim, competition was strong, and his friend was facing severe financial issues.

“He wasn’t sure it was sustainable,” Rabbi Tenenbaum remembers. “I said to him, ‘Let’s talk after Shabbos.’ And somehow he convinced me to go into business with him.”

Eventually, Rabbi Tenenbaum bought his friend out, viewing it as a business opportunity for his chassidish sons who wouldn’t attend college. When he joined the industry, it was stagnant. Issues in halachah and comfort were rarely addressed, and tallis bags and coverings for sifrei Torah were, for the most part, standard stock items. Many men walked around with old, yellowed talleisim and the majority of them carried similar velvet bags.

Rabbi Tenenbaum, a self-described “simple guy, a businessman who tries to solve problems,” knew he wanted to change that.

“ ‘Zeh Keili v’anveihu,” he says. “I wanted to make these mitzvos as beautiful, as halachically acceptable, and as comfortable as possible.”

He started learning the relevant halachos, and as his awareness and enthusiasm for the mitzvah grew, it wasn’t long before Rabbi Tenenbaum became the go-to address for all questions about tzitzis and talleisim.

“I was in it, I learned about it, and people kept asking me questions,” he says. “It’s a daily mitzvah, but people didn’t have much knowledge.”

Over the years, Rabbi Tenenbaum has given lectures on the topic and written several seforim about the mitzvos of Tallis and Tzitzis. And as he delved into them more, he came up with ideas and enhancements — what he fondly calls “chiddushim” — for the mitzvos. But before implementing any of them, Rabbi Tenenbaum had to confirm his concepts were halachically sound, and he consulted with many gedolim.

For example, tzitzis knots inevitably become loose and unravel over time — and when the knots come out, the tzitzis are passul. You can tighten them without remaking the entire garment, but tying or tightening knots is forbidden on Shabbos. In fact, one should not even check his tallis strings on Shabbos for fear that he will automatically tighten the knots.

The easy solution, explains Rabbi Tenenbaum, is to place glue in the knots, holding them securely in place. However, there is a diversity of opinions when it comes to this solution.

“Rav Asher Weiss holds that the glue in the knots is a hiddur, not only for mitzvas Tzitzis, but for Shabbos as well, because he is very concerned about chillul Shabbos,” Rabbi Tenenbaum explains. “Other rabbanim told me not to do it, because the glue negates the kesher. Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv ztz”l told me it was okay to put very little glue into the knots, so if someone wants to open it he could still do so. Rav Shmuel Wosner ztz”l felt that the issue of chillul Shabbos was so significant, he wanted me to put a bit of glue into the knots but not to publicize it.”

To accommodate all opinions, Rabbi Tenenbaum went in another direction, concocting a spray that stiffens the knots and secures them in place. The project was put on hold due to Covid travel restrictions, but he plans to resume it once he can travel back and forth easily to discuss it with the gedolim.

Another tzitzis-related issue is that the fringes are supposed to hang over the sides, but that defies gravity. Keter inserts a soft material into the corners of the garment to prevent the strings from falling downward. They also place glue at the bottom of each string so they won’t unravel, because that can make the tzitzis passul.

Aside from questions about strings, Rabbi Tenenbaum is often asked if cotton tzitzis, as opposed to wool, are permitted. “Cotton is, because it’s woven,” he explains. “Undershirt tzitzis are more of a question.”

With enough wear and tear, tzitzis can become torn at the front of the neck, and a significant tear can render them passul. Simply sewing it is not a solution, because the strings would have to be removed before sewing the tear and reattached once the garment is fixed for the reconstructed pair to be considered kosher. To solve this issue, Keter sews a lightweight band into the collar. This barely visible band is extremely strong — to demonstrate exactly how strong, Rabbi Tenenbaum and his son-in-law each hold one side of the garment and pull hard from both ends.

Coming up with solutions to enhance how we keep these mitzvos gives Rabbi Tenenbaum great satisfaction. “If people can do the mitzvah better because of me, then it goes onto my score card,” he says with a smile.

Pack Your Bag

Custom tallis bags have become popular over the past decade, and customers can request a tallis bag made out of almost any material today, from alligator to giraffe skin. Most are sourced from cow and calf hides from tanneries around the world; the only materials Keter won’t use are those that are illegal in the United States, like sea lions. But it’s not just a matter of color or font; some clients go extremely personal with their tallis bag design because everyone has their own interpretation of “zeh Keili v’anveihu.”

A man named Arye Leib requested an intricate embroidery of a lion on his tallis bag. Ber requested a bear.

A Hatzalah member asked for a stitched zigzag line to reflect an EKG heart monitor.

A devoted Shomrim member ordered yellow suede with royal blue stitching to match the organization’s logo.

A Ferragamo dealer requested the designer logo on his bag.

A client from Toms River wanted to stand out with a statement bag, so he ordered an orange-quilted bag trimmed with white fur, and a matching orange atarah for his tallis.

A Lakewood askan recently purchased a tallis and tefillin bag for a Jewish state trooper who was putting on tefillin for the first time. He ordered it in yellow and blue to match the state trooper logo.

Due to recent events, a customer in Lakewood ordered a special pocket in his tallis bag with a double safety zipper to hold his gun.

A Gift for Her

A Satmar chassid who wanted to buy a unique gift for his wife settled on a sefer Tehillim covered in zebra skin, which cost more than $600. The head of production stood over the machine, guiding it, to ensure that the wife’s name fit perfectly with the curve. Another client bought a tallis bag and tweaked it a bit as a custom leather pocketbook for his wife.

Heads Up

Keter is getting a lot of yarmulke orders for the current look of embroidered symmetrical lines. Purim time, embroidered words are especially popular, with slogans like “Make America Great Again,” or Shishah Sidrei Mishnah on each section of the yarmulke for a proud talmid learning Mishnayos. While the bestselling yarmulke is still black velvet, these products are available in hundreds of styles, sizes, and materials. It varies by age — kids and cool teens wear the super-funky yarmulkes (think: orange and neon-colored) — and location: Keter’s Lakewood store sells a lot more fashion yarmulkes than the Williamsburg store, which sells virtually zero. Regardless of color or design, all Keter yarmulkes have a hechsher — they’re made of linen, wool, cotton, or other reprocessed materials, which can present big shatnez questions, so a shatnez lab checks each shipment.

Curtain Call

Chassidish shuls tend to order more classic styled florals and curves for their design, but the more modern look, requested by some of the younger shuls, includes a combination of leather and velvet and has fewer curls, swirls, and flowers, and more simple geometric and artsy themes.

Most expensive: An $18,000-paroches encrusted with hundreds of Swarovski crystals, from the top, where the crystals surrounded a pasuk, all the way to a heavy assortment at the bottom.

Largest: A 12-foot high paroches for a shul with cathedral ceilings. The background material was a linen look that had to be maneuvered by several workers at the embroidery machine.

Smallest: For a chassidish family with a precious yerushah — a mini-sefer Torah that had been smuggled by its owner during the Holocaust. Measuring the Torah wasn’t simple, because the family brought it into the warehouse but would not let it out of their hands. It was only seven inches long, and the mantle a mere five inches. The mantle was made of cow fur, with a small crown embroidered on it with the words “Kesser Torah” (there was no room for anything else).

Torah to Go

There has been an increase in orders for cases and mantles for traveling sifrei Torah. One option is a leather bag with wood and leather at the bottom to hold the Torah in place. A customer once brought a large suitcase for his traveling Torah and asked that it be turned into a traveling aron kodesh. Keter crafted a foam insert to hold the Torah and designed a leather mantle for the Torah, with a coordinating cover for the suitcase.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 913)

Oops! We could not locate your form.