Snatched from the Eagle’s Claws

| April 11, 2022How the Third Reich preserved a treasury of Jewish books

Photos: Elchanan Kotler

W

hen Rabbi Nachum Zitter, studying in the library science track of an Information Technology master’s degree program at Bar-Ilan University, told his family that he’d been assigned to keep a daily library blog, their reactions ranged from disbelief to shouts of laughter.

“What will you write about every day?” they asked him. “Monday, someone talked in the Reading Room, and I told him to be quiet. Tuesday someone talked in the Reading Room and I told him to be quiet. Wednesday…”

You get the idea. Keep a library blog? What can you say about libraries, stuffy places where there’s really nothing to get excited about except the occasional reader speaking in a loud voice who needs to be shushed?

Full disclosure here: Nachum is my son, my bechor. Fuller disclosure: I was one of those who laughed at the idea of a library blog.

One final disclosure, and a confession: Boy, was I ever wrong.

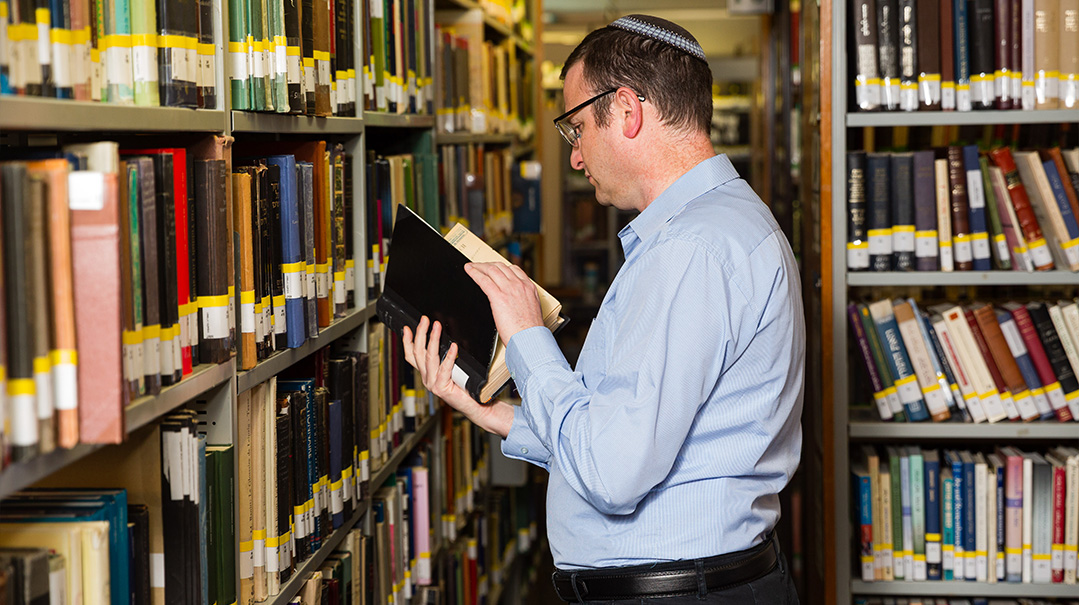

Turns out the National Library of Israel, where Nachum is now Head of Reference Services, is a fascinating place, teeming with complex characters and compelling stories both inside and outside of the covers of the books.

Here is the story of how one librarian, Daniel Lipson, found a piece of his family’s story in an old notebook, a find that led him to discover a treasure trove from our people’s tragic history.

Here is the story of books destroyed, books saved, books returned and reclaimed.

Here is the story of a collection known as Otzrot haGolah — the Treasures of the Diaspora.

And it all happened in the library…

Nothing by Chance

Librarians are trained to do intensive research into whatever topic they’re looking into — but they also know that sometimes you can bump into something interesting, seemingly by chance.

“Serendipity, finding something valuable that you haven’t been specifically looking for, is one of my favorite words,” says Daniel Lipson, reference librarian at the National Library.

Lipson, a young father of seven living in Ramat Beit Shemesh, uses the word serendipity to describe his initial find, one that led him to years of research into Otzrot haGolah. Lipson was simply looking through an archive of pinkasei mohalim — registers of bris milahs kept by mohalim in pre-Holocaust Europe. The National Library owns hundreds of such notebooks. Suddenly, he was shocked to find a pinkas kept by his great-great-great-great-grandfather, Rabbi Yoseph Hackenbroch from Deutz, Germany, recording brissim from 1804 to 1831.

“I was especially moved to see that my great-great-great-great-grandfather included a record of the bris he gave his own son, Eliezer, since my son, Yonatan Eliezer, shares that family name,” Lipson told me.

Lipson’s find was serendipitous (or, we might say, it was simply bashert). But after that first lucky find, he was inspired to do more research, and that’s when his family’s history led him to the larger story of his people.

Provenance is another word librarians enjoy using. It means a record of where something came from — where it originated, and how and when it was finally acquired, be it a work of art, a piece of antique furniture, or, most often in libraries, a manuscript or a book.

Lipson wondered how, when, and from where the National Library had gotten hold of his family heirloom. He asked a colleague in the Manuscripts Department, who told him that its library provenance was Offenbach 1946.

Offenbach 1946. It was an answer that opened up many other questions. How had a pinkas mohalim written in Deutz ended up in a city just outside Frankfurt? How had the pinkas survived the Holocaust? And how had it made its way from a Europe devastated by a world war to Israel’s National Library?

Lipson turned to some of the older librarians with his questions. And that’s where he first heard the words Otzrot haGolah, literally, the Treasures of the Diaspora. Ironically, these books — sifrei kodesh, community records, children’s books, science texts, works written in Hebrew, Yiddish, Ladino, and European languages, had been saved from destruction during the Holocaust… by the Nazis themselves.

Dark Plans

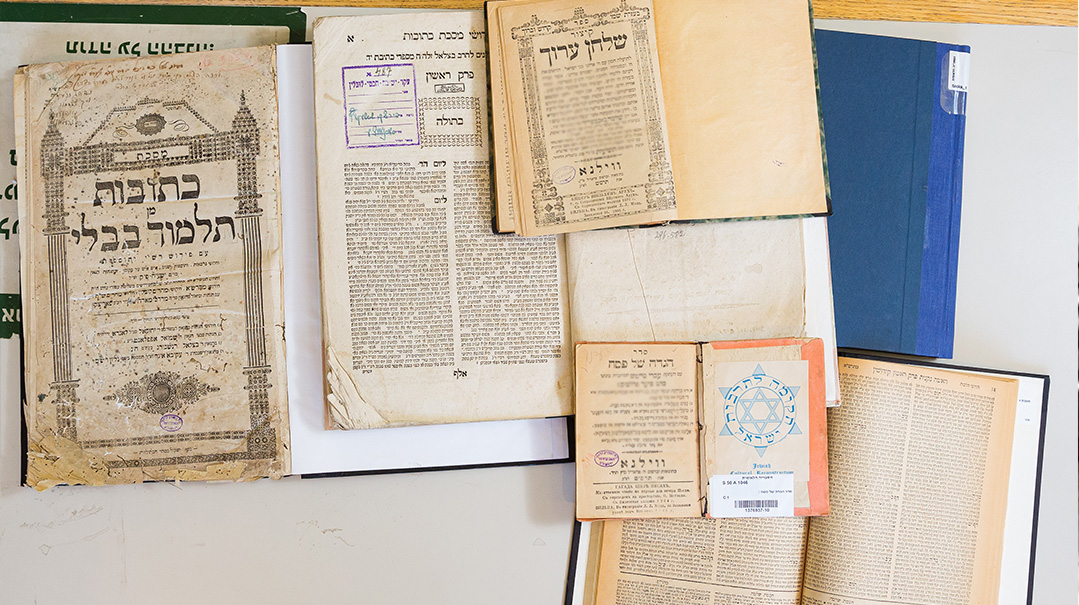

The books that became known as Otzrot haGolah originally came from all over Europe. They were brutally seized from bookshelves in private Jewish homes, looted from libraries, or stolen from yeshivos and batei medrash.

The Nazis burned millions of Jewish books, but this collection was meant to suffer a different fate. These stolen books formed the basis of a collection the Nazis planned to use as a future library of Jewish texts.

Nazis collecting and reading Jewish books? Not as strange as it sounds. Their dark plan was to establish a major university after the war, centering on Nazi ideology. The idea was to collect Jewish texts that would be studied by Nazi professors and scholars looking for proof to back up their anti-Jewish ideas. As Lipson put it, “their theory was, know your enemy. The enemy, of course, were the Jews, and the way to know them was through their books.”

The Institute for Research into the Jewish Question was established in 1941 and was meant to become a center for study for the planned university. The Institute was founded by Alfred Rosenberg, an important Nazi figure who was hanged for his crimes after the war. Rosenberg’s ideas and writings formed the ideological basis of Nazi anti-Semitism, and as the German Army overran and occupied Europe, Rosenberg ordered his task force to send the plundered books to the library at his Institute in Frankfurt.

By war’s end, the Nazis had collected millions of volumes. In addition to several other collection points, about two million books found their way to Rosenberg’s Institute. Ironically, many of the stolen books were housed in Frankfurt’s Rothschild Library, established as a free library in 1887 by Hannah Louisa von Rothschild, descendant of the most well-known and prominent Jewish family. Rothschild’s gift to the German people became a Nazi storehouse for plundered Jewish treasures.

As the war progressed, the Allies began bombing Frankfurt, and the Nazis moved the books to castles and warehouses and schools outside the city to protect them.

“The Nazis who put so much thought and planning into killing Jews, put so much thought and planning into saving their stolen Jewish books,” Lipson noted.

Off to Offenbach

And finally, the war was over. Those few Jews who had survived the horrors of concentration camps, the torture of death marches, the suffering in ghettos and labor camps, moved through Europe on foot or by train, sometimes hitching rides with American or Russian soldiers. Some found their way back to their homes — and all too often found those homes had been destroyed or stolen by their non-Jewish neighbors. Many made their way to Displaced Persons camps established by the Allies. A lucky few received permission to go to America; others found ways to get past the British blockades to the Promised Land.

And then… there were the books. The American Army was given the immense task of sorting the millions of volumes that Rosenberg and his Nazis had plundered. The Rothschild Library couldn’t hold the crates upon crates of books the Nazis had collected from all over Europe and that now needed to be dealt with. A large, central warehouse was needed — a kind of DP camp for Jewish books.

The American Army found that place in Offenbach, a town near Frankfurt. A large, five-story building with a warehouse became the Offenbach Archival Depot (OAD). In a chilling irony, the building was part of a manufacturing compound owned by Germany’s mega-chemical company, I.G. Farben, manufacturers of the Zyklon B gas used in Auschwitz. Two million Jewish books, seforim, even sifrei Torah, now were stored in a building owned by a company that used Jewish slave labor and whose subsidiary manufactured the gas that murdered many of these books’ original owners.

The US Army chose Colonel Sholom Jacob (Seymour) Pomrenze to begin the herculean task of sorting the books and tracing them to their original homes in order to return them, whenever possible. While Pomrenze, who had grown up in an observant home in Chicago, came with a background as an archivist, he described how overwhelmed he felt when he first arrived in Offenbach in a blinding winter snowstorm. He was greeted by the sight of thousands of crates of books from all over Europe. Many of the volumes were damaged, none were cataloged, and he had just a handful of workers to search each and every volume for a clue as to where it came from: which country, which library or yeshivah, perhaps even which Jewish home, now lying in ashes…

Years later, Pomrenze wrote that when he first arrived in Offenbach, he estimated that at the rate the work had begun, it would take 20 years to finish the job. He immediately hired a larger staff, and, working with another Jewish officer, Captain Isaac Bencowitz, began what just might have been the most massive library operation in history.

Reading the Fine Print

So how does one go about identifying and sorting millions of stolen books? This wasn’t a matter of a trained staff of librarians sedately organizing volumes by the Dewey Decimal or Library of Congress cataloging systems. Bencowitz, who succeeded Pomrenze as director of the operation, used his background in industrial management to create a step-by-step, conveyor belt system to organize the search.

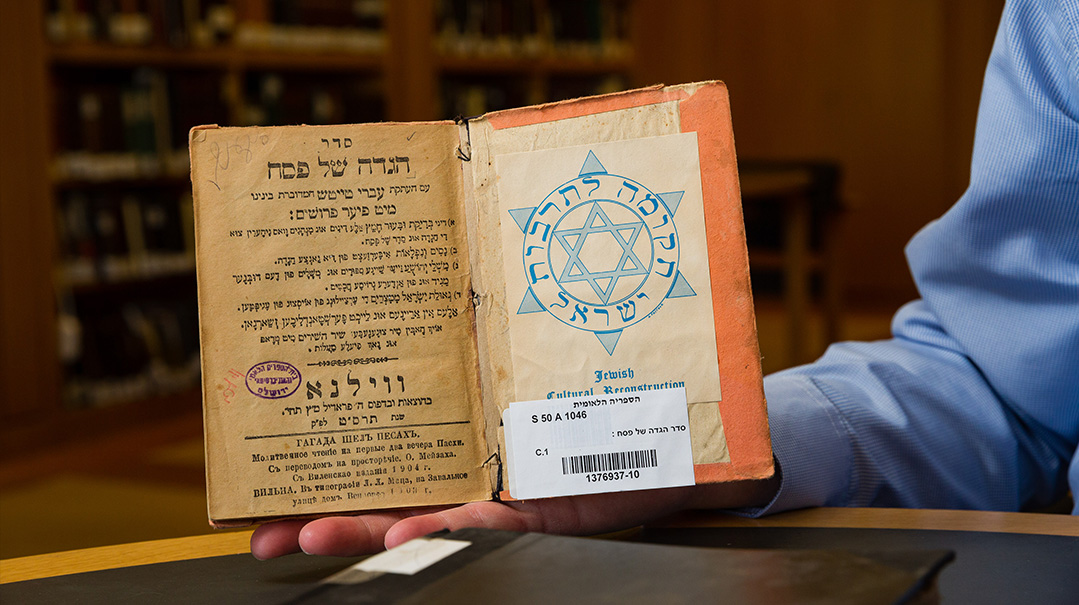

“Ex Libris,” another phrase librarians use regularly, literally means “from the library of,” and book owners, schools, and libraries used to print or write it on a “bookplate,” that is, a label, printed or hand-decorated. These bookplates were pasted into the inside front cover or first page of a book, with the name of the book’s owner or library. Other books, especially from smaller libraries and yeshivos, had an identifying stamp inside their covers. For Bencowitz, Ex Libris bookplates or stamps provided the first clue in solving the mystery of each volume’s original source.

Bencowitz began by identifying and photographing Ex Libris bookplates and different book stamps from different countries, noting differing styles, colors, and shapes. He collected the photographs in two massive volumes, one covering Western and one Eastern Europe.

Once the albums were completed and the staff had become familiar with the different bookplates and stamps, the work of sorting the books could begin. The books went down a conveyor belt, and staff members, most of whom were Germans who didn’t know the languages of the books, opened each one and quickly sorted the volume by country of origin, based on the Ex Libris or stamp style. Using this innovative system, Bencowitz and his team were able to identify hundreds of thousands of books from libraries, yeshivos, community organizations, and even individuals.

Sorting the books wasn’t the only challenge. Many of the books had suffered damage by fire, water, or mold, with pages and book covers bent or ripped. Bencowitz had earned a master’s degree and a PhD in chemistry from Columbia University, and he used his scientific knowledge to create ways to treat damaged books. He had some help here from an unexpected source: a former monk who had worked on restoring documents in his religious order. Among his other tricks, he used clothespins to hang books up near a heat source to dry them out.

After giving away his kosher rations to survivors, Rabbi Rackovsky had another mission: to sort through thousands upon thousands of books and documents looted and preserved by the Nazi

A Dose of Yiddishkeit

Using Bencowitz’s system, the books were sorted by country. But a crew of German workers (including the former monk) could only go so far in identifying the works; they couldn’t distinguish between secular texts and sifrei kodesh, much less understand the value of those seforim.

Enter a number of volunteers, knowledgeable Jews who knew the difference between a sefer and a secular book, who could recognize a Gemara or a Shulchan Aruch, and who would be able to figure out if a text was likely stolen from a shul or a school, a yeshivah or a library, a beis medrash or a university.

One of those volunteers was US Army chaplain Rabbi Isaiah Rackovsky. Rabbis weren’t generally drafted, but Rabbi Rackovsky, rav of a kehillah in Omaha, Nebraska, had volunteered to join the US Army. “The sons of his parishioners in his shul were drafted and fighting in Europe, and he felt he couldn’t look them in the eye if he didn’t join up,” his son, Dr. Shalom Rackovsky, recalled.

When Rabbi Rackovsky came to Offenbach, the tall young officer weighed only 120 pounds; there was so little kosher food available for him to eat in his earlier postings. His wife would send him care packages — which he promptly distributed to the Jews in the DP camps where he visited.

One of Rabbi Rackovsky’s jobs was to examine and identify thousands of looted documents. Official estimates suggest that he looked through and classified 5 cubic meters (that’s about 32 square feet) of books and documents.

“My father brought his Hebrew, his Yiddish, and a large dose of Yiddishkeit to this military operation,” Dr. Rackovsky said.

Undercover Escape

With a workable system in place to sort the books, now came the point of it all: to return them wherever possible. The legal, political, and practical implications of this part of the operation were complex, but the Offenbach Archival Depot (OAD) succeeded in its mission: Between 1946 and 1949, millions of books were returned.

One of the earliest shipments was arranged by Professor Koppel Pinson, a historian who joined the American Army at the end of the war to help Jewish refugees. He worked at Offenbach, and arranged for thousands of books to be sent to DP camps for use by the Jewish refugees.

Daniel Lipson’s family pinkas mohalim also left the OAD in an early shipment — but not exactly legally. Immediately after the war, only recognized states were allowed to receive the books. Boatloads and trainloads of books headed back to Holland, France, Russia, Italy, and Germany. But there was one problem: the State of Israel, homeland of the Jewish People, didn’t yet officially exist. Hebrew University and the National Library sent a well-known scholar, Professor Gershon Scholem, to the OAD to assess the situation. He reported that Jewish seforim and community records sent back to Eastern Europe, where Jewish life had been decimated, would be lost to the Jewish People.

Scholem decided that the Jews of Europe had lost enough, and he managed to smuggle five cases of rare books, seforim, manuscripts, and community documents out of the OAD and into Palestine. He had them sent to Antwerp, and the cases, which included Lipson’s family pinkus, arrived in Israel by boat. They docked in Haifa in 1947, coming to Palestine as part of a shipment of personal items belonging to Chaim Weizmann, soon to be the first president of Israel. When the Americans found out about the illegal shipment, they agreed to allow it to stay in Jerusalem — at the National Library.

Despite their success in returning millions of books, by 1949, hundreds of thousands still remained at the OAD, their provenance impossible to determine. And now a new concept emerged, one that justified Scholem’s “illegal” action. These books would be returned, not necessarily to their countries of origin, but to the people who had written, read, and revered them — to the Jews. An organization called the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction (JCR) was created and recognized by the US Army as the trustee of Jewish materials that couldn’t be returned to their place of origin.

From 1949 to 1952, the JCR distributed about 500,000 books to libraries and yeshivos worldwide. Thousands of those books were sent to Israel’s National Library — where some 70 years later, Daniel Lipson found the pinkas mohalim that began his search for Otzrot haGolah.

A Living Collection

Having discovered the fascinating history of his family treasure, Lipson decided to examine the whole collection of JCR books owned by the National Library. But he faced one major hurdle: The collection of books wasn’t really a collection at all. This treasure was buried — in the stacks and stacks of the library’s vast holdings.

Once the National Library accepted books from the JCR, they were then simply placed on the shelves categorized by their content, ready to be used by readers and researchers, most of whom would have no idea of the dramatic story behind the volume they were reading.

The only hint that these “rescued books” differed from other texts on the shelves was a JCR sticker placed inside each front cover — and the letters alef-gimmel, standing for Otzrot haGolah, written by hand in the library’s “accession books,” mammoth binders in which librarians recorded each new acquisition as it came in.

Still determined to find out more about these treasures, Lipson pulled out accession books from the years 1949 to 1959, doggedly reading the cramped print of thousands upon thousands of entries, noting those that bore the significant alef-gimmel in the column marking the provenance. The work was difficult, but Lipson had a dedicated team helping him: his own children, who combed the accession books looking for the precious alef-gimmel. When a rescued book was identified, Lipson faced another colossal task: tracking down the books, which hadn’t been recorded in the library’s computerized records.

It took a year and a half, working on his own time, but Lipson waded through ten years of records. He identified some 10,000 works, mostly written in Hebrew and Yiddish.

Though scattering these books throughout the library’s collections made Lipson’s job more difficult, he doesn’t feel it was a mistake. Kept as a special collection, people might have looked at the books through glass, like in a museum; this way, this treasure trove of books actually gets used in a living, dynamic library.

And what treasures these books are. On Tishah B’Av, Lipson reads Kinnos from a JCR volume. “I wondered if the last person who used it, maybe 80 years ago, realized that Churban Europa was imminent,” he told me. On a more cheerful note, he has used an Otzar haGolah volume of Megillas Esther on Purim and a Haggadah on Pesach.

Lipson recalled an incident in which a woman asked a librarian for a siddur to daven Minchah. The woman got the shock of her life when she opened the siddur and saw a picture of the Nazi eagle, symbol of evil. The librarian had to explain to her the whole story of the looted books — and their return through the JCR.

Letters of Light

May 1933. Forty thousand Germans pack the Babelplatz, a central plaza in Berlin, cheering 5,000 Nazi students and professors as they burn 20,000 Jewish books. Five years before Kristallnacht, six years before Germany will invade Poland, a fiery glimpse into the horrors of the Holocaust to come.

A century earlier, Heinrich Heine, a German-Jewish poet whose works were burned that day, foresaw the grim future. In 1820, he wrote: “Where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people as well.”

Today, those frightening words stand on a plaque marking the place of the book-burning, part of a memorial created by Israeli artist Micha Ullman. The memorial, an underground room full of empty bookshelves, is known as “The Empty Library.”

In a few weeks, the National Library of Israel will begin the move into its new, permanent home. Set in extensive campus gardens (planted months ago, before the building was finished, in accordance with shemittah) stands another work by Ullman, a companion piece to his grim Berlin memorial: Letters of Light, an art-installation of stone-hewn letters of the alef-beis that reflect the changing shadows in the golden Jerusalem sunshine.

The Nazis burned our books, murdered six million of our people. But they couldn’t destroy our wisdom, our spirit, or our faith.

One Last Move

In just a few weeks, the National Library will begin the monumental task of moving from its current home on Hebrew University’s campus to a brand-new building across from the Knesset. The project has been decades in the planning, and moving the millions of books, manuscripts, microfilms, and maps will take many months.

And the hundreds of truckloads of books making the move will include the rescued books of Europe, coming to their final destination in their new permanent home, in the middle of Jerusalem. Their physical existence is miraculous; but even more miraculous is the fact that while the ideologies of our enemies are long gone, our seforim continue to live on.

“When I hold a JCR Gemara,” Lipson says, “I imagine a yeshivah bochur in prewar Europe, enjoying its wisdom so many years ago. Then I see a Nazi professor, poring over it, looking to fuel the murderous Jew-hatred of his people. And finally, now I can actually see a yeshivah bochur in Jerusalem studying that same Gemara, reveling in the ancient words, reconnecting the sefer to its people.”

And it all happened in the library….

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 907)

Oops! We could not locate your form.