Fare Exchange

| April 11, 2022I don’t know what’s pulling me to this young mother — or maybe I do

E

veryone is looking for something. Thing is, they don’t always know what that something is.

I see them in the rearview mirror, the barely out-of-teens looking for jobs, independence.

I see them, the young marrieds with babies, in a desperate quest for decent living quarters, sleep, and reassurance that they’re not making a mess of the parenting thing.

I see them, the stressed businessmen and women, the fidgeting middle-aged, the harried and the hurried — all searching, searching.

Now I glance at the mirror, studying the rear seat’s occupant. He’s in a rush. Aren’t they all? An interview, probably. He’s gone through the papers in his briefcase five times, yanked the knot on his tie to choking point, and keeps slicking back invisible hair.

He riffles through his billfold and silently shoves the money over my seat. He, for example, is looking for respect. He won’t get it if he doesn’t show it to others.

The car shudders as he slams the door, and I carefully ease into the lane of flowing traffic.

I know people pay me, but the world would be a better place with more kind words.

I slow down near a school for my next fare. The woman shoves a few bags onto the seat before sliding herself in, phone jammed against her shoulder.

“Eleventh and Fifty-second,” she says, breathless, and continues a high-spirited phone conversation about bus schedules.

She’s just looking for time; I can feel quick-quick-so-much-to-do oozing off her. I wonder what would happen if she stopped to look at me — would she feel how much of my own time yawns at me, empty?

When we get to the corner, she directs me to a brownstone house and pays me quickly, thanking me as she snatches the bags and hurries out.

I’m about to drive off when I hear someone call taxi!

It’s a young woman with short hair and a hat, jittery with an overabundance of nerves.

“Oh, I’m so happy you’re here, finally! We’re a few houses down, the dispatcher said no taxis were available, but I guess he found someone! Can you come back a bit?”

It’s obviously a misunderstanding, but the woman is off and running so I reverse.

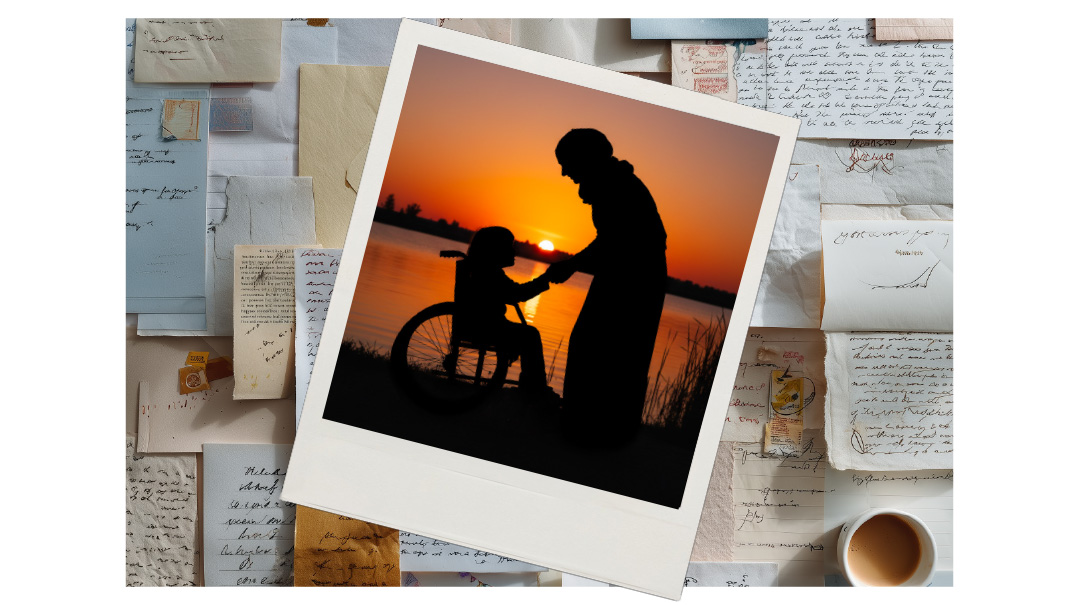

I don’t like dealing with equipment. But I have that conscience Mama gave me, so I get out and help the lady wrestle a wheelchair into the trunk. I draw a line there, though, so I sit silently while she gets her child settled, trying not to think of Rosie.

“We need to get all the way to Marine Park! I hope we’re not late for our appointment. There’s a lot of traffic now, right?”

I tell her not to worry, I’ll do my best. I don’t say that this must be a mix-up, no dispatcher besides Mama brought me here.

I watch her carefully at every red light, this young woman fussing over her disabled child. It’s like someone banging a deep, harsh note out of my chest. Rosieee. I focus on my passenger — huge eyes, deep dimples. She doesn’t seem old enough to be a mother. She’s just a girl herself! She prattles lightheartedly in what I recognize to be Yiddish, a language familiar to me from childhood though I can’t follow the conversation.

The traffic clears once we hit Avenue N.

“Wow, I think we’re going to make it on time!” The girl leans forward, smiling. “And I didn’t even ask you your name, I’m sorry. I’m nervous, it’s our first appointment. I’m Rivky.”

She’s waiting. This is new. Who asks for my name?

I clear my throat.

“I’m Masha.”

“I’m so happy you came. Masha — do you take private rides too? I need to come here weekly for a new kind of therapy, it’s a long drive, but so many people say they’re happy… anyway, it’s just that I’m more comfortable with, um, a lady driver.”

I nod.

Wondering what to do with almost an hour to spare, the hollow in my stomach reminds me I’ve skipped lunch. I pick up a bagel on Nostrand and Quentin and find a shaded spot where I eat slowly until it’s time to pick them up.

After the 30-minute ride back home, I unload the wheelchair while Rivky struggles with the child.

Heading toward Brighton Beach, I wonder what on earth possessed me to give this girl my phone number and commit to doing this every Tuesday. I must be getting soft.

I actually do know what on earth it is but I don’t want to think about it.

Everyone is looking for something.

But right now all I’m looking for is somewhere to buy a hot soup.

I settle into some kind of routine on Tuesdays, trying to find rides near Boro Park so I don’t waste too much unpaid time getting there to pick up Rivky and her child. I don’t know why I’m doing this, I do know why I’m doing this, ay, I shouldn’t do this.

I help her with the wheelchair and any other bags she has. And she always thanks me so prettily, this Rivky.

When we drive home, Rivky is always quieter, tiredness sliding off her; the child lolling against her in semi slumber. I make sure the radio is off and try not to use the horn.

One afternoon we’re almost there when there’s a sharp exclamation from the back seat.

“Masha!”

I jerk and resist the urge to slam the brakes.

“What, what?”

I hear the retching and a sour odor fills the car. I try not to breathe in as I open all the windows and pull over.

“Do you need tissues?” I ask. I really don’t want to turn around to see what’s going on.

“No, we’re fine. I’m so sorry I yelled, I thought my daughter was choking. I have wipes.” A rustling and the sound of a bottle being opened. “Let me run out and find somewhere to put the bag.”

I nod and she scuttles out, leaving the two of us for a long few seconds before she jumps back in.

“I’m so sorry, Masha. My daughter doesn’t usually throw up, I didn’t think… anyhow, I cleaned it all up.”

I nod again, my stomach roiling as we merge back into traffic. It’s never pleasant when someone vomits in my car, but now it rankles. I try to think of other things, not Rosie — things I need to buy, my friend Nina’s move here next month — when I hear a little sniffle.

I glance up at the mirror and see Rivky holding a tissue to her eyes. Her shoulders are shaking and my heart, the one Mama always told me I hid behind too many layers, makes me do something I’ve never done in all my years of driving.

“Do you want me to stop the car?” What’s that going to help? It’s the wrong thing to say, but I need to say something.

“N-no, Masha. Thank you, I’ll be okay.” I hear the shuddering breath and know how not okay she is. I’ll respect that, though.

I can’t help thinking of Rosie then. Even after I drop Rivky off, the memories are sharp and unrelenting.

I drive straight home to the silence I know so well.

Nina’s plane landed on time, but it’s taking her hours to get through border control.

At the airport, I watch humanity’s ticking need to rush-rush-rush. People fidget as they await their loved ones, flowers and balloons clutched in sweaty fists. Taxi drivers with carefully lettered posters held at chest level crane and stretch their necks as tired passengers stumble through the electric doors. Will this be him? This?

Nina finally texts me that she’s out. We hug quickly, and I pile her luggage into the car, the suitcases that don’t fit in the trunk stacked neatly on the back seat. A shadow crosses her face. “Ay, a lifetime,” she says quietly. “And in the end, all of it in one car.”

“You must be exhausted, usually traffic’s not too bad at this hour.” I look over at Nina as she leans back. We slide easily into our native Russian, conversation light as we head toward my apartment.

“Tea and vatrushka and bed,” I tell Nina, as I snatch small glances at my best childhood friend. Widowhood seems to sit uneasily on her; the pain of Yasha’s loss is still fresh. She’s looking for companionship, for comfort. I’m an old hand at this. I’ve been alone for so long now; I’ve almost forgotten what it means to wait for someone who will never come home again.

“It’s good we planned for me to take off this week until your apartment is available. Ah, you’ll enjoy New York!” I say. But Nina is already dozing.

As I park, Nina shakes herself awake.

“Izvini, Masha. It was a long flight.”

“Nyet, nyet, don’t apologize! I’ll get your things upstairs, Mama’s samovar is ready for you.”

She smiles, and I’m grateful for her, someone who knew me and Mama and everything I used to be. Her daughter Viki is away for a conference this week, so for now, I’m all she has here.

“I’m sorry to leave you for an hour or two, there’s a job…” something kept me back from canceling Rivky, “…a weekly commitment, you know?”

Nina’s fine. I put her hand luggage next to the bed I prepared for her, show her around the kitchen, and leave.

Somehow, I’ll find a way to tell Nina about Rosie. The one thing I haven’t shared with her.

I get out of the car and stow away the wheelchair easily.

“Hi, Masha, how has your week been?”

“I’m okay, Rivky.”

I pull out and turn onto 52nd Street.

“I have something for you, Masha,” Rivky sticks her hand between the two front seats. It’s a foil-wrapped package.

“My baby turned two! It’s from his birthday cake.”

I choke back my astonishment. Cake? When has anyone ever given me cake?

And Rivky has another child?

“Thank you.” I fumble for words. “I… I’ll save it to have with my tea.”

Embarrassment makes me taciturn.

Rivky doesn’t mind. She’s the kind of person who fills up empty spaces with talk.

Nina and the explaining I’m going to have to do later are weighing heavier on me than I realize, and my next words blurt themselves out.

“Does your daughter have CP?”

Rivky’s eyes widen as she glances down at her child.

“Yes. She does. How do you know, Masha?”

That’s how a young almost-stranger from Boro Park is the first one to hear the story I’ve held in my heart for so long.

“Mama, Mamatchka, you must come quick!”

That’s how the whole thing started — me with passengers on the way to Coney Island and Rosie’s hysterical voice filling the car.

“Shush, Rosie. What happened? I have people in the car.” But she didn’t listen, just carried on — her hysteria infectious.

Her words were garbled, disjointed, or maybe that was me, unable to understand. The minute I heard her say hospital, I was incapable of coherent thought besides one — I needed to get to my daughter.

Thankfully, my brain carried me to our destination and I fumbled with the change before speeding off, reassuring Rosie that I was on my way and mumbling prayers to no one in particular that the most precious thing I loved would be okay.

But she wasn’t.

I got lost in the warren of hospital corridors, bumping into strangers and chasing after rushing people in surgical scrubs. When I finally managed to locate someone who knew what was going on, Rosie was already in surgery. Twenty-eight weeks, no. No.

“What happened, Adam, what happened?”

I didn’t get along very well with this man my daughter had chosen to marry. But I always made an effort to put on a civil front for the sake of my daughter.

Adam fiddled with his keys, avoiding my eyes. I’d only find out later why this was his fault.

“Pre-eclampsia?” he said, like it was a question I had the answer to.

There were no answers, though, not even time for asking more as the birth of my grandson was overshadowed by the worry that I’d lose them both. I didn’t know where to go, where to put myself as Adam hastily donned a mask and scrubs and ran after the doctors to the NICU, where I’d spend the next few nightmarish weeks.

“They both lived, my Rosie and her son,” I tell Rivky as we arrive at her appointment.

She nods, her mind already outside, so I get out and open the trunk, leaving the next words unspoken.

But they were both broken, and I couldn’t fix it.

An hour later, I pick them up. Rivky is tired, she doesn’t need to listen to a bitter, lonely woman unburden her secrets. But the memories suddenly sit too heavy on me, and I talk anyway.

The baby was six months old. Scrawny, but his cheeks had filled out. If you held him close, you wouldn’t notice the clenched hand, the limp legs. But we knew, Rosie and I. We saw it all.

A life sentence.

My poor Rosie — and Adam gone, looking. Looking for freedom, for a place where his guilt wouldn’t stare him in the face every day.

Day after day, I worked from morning to night to support the three of us, watching the color drain from my Rozatchka, my rose, her entire being consumed by the child she wanted to heal. I stood by, helpless. Her residency! All those years and years of university and medical school, for what? I looked ahead to see her future forever weighed down with this burden and it terrified me.

I couldn’t do it anymore. I couldn’t watch it happen.

I look up in the mirror to see if Rivky is still listening, then drop my eyes back down to the road.

“I told her she should put the child in an institution.”

Rivky is silent. I force the next few words out, the bitter taste in my mouth sharpening with each syllable.

“And she moved out and we never spoke again.”

I get out of the car, feeling old, old, old as I drag the wheelchair out and look at Rivky.

Ice touches my heart as she looks back at me, eyes dark, the bag with the exact change she gives me every week dangling off her fingers like it’s contaminated.

“I don’t think it’s a good idea if you come back next week, Masha.”

Every word a stone slamming my already bruised heart. Every word one I deserve.

And just like that, I’m a pariah once again.

I’m not sure if Nina being here now is a blessing or a curse.

I park the car and slowly make my way up the stairs, putting pieces together in my mind, but when I walk in, I’m relieved to discover Nina sleeping.

The next day goes as planned — I show Nina the Statue of Liberty, proudly taking her on the ferry. It’s on the way home that Nina finally asks.

“So, Masha, when will I get to see Roza?”

Here’s the thing with having your best friend live at the other side of the world. You can pick and choose whatever you want to share. You don’t lie, really; you just build a reality around the truth you want to omit.

“Roza can’t come this week, her son hasn’t been feeling well.” I tiptoe through the carefully constructed tale in my head. “You know, with his compromised immune system it’s dangerous for him to see anyone now.”

Nina looks at me. I can see her wondering how much she can say.

“Nu, so we can’t go to where she lives and stand near the door to blow kisses?”

A physical pain radiates across my chest.

“Nyet, Nina, she’s so worried, so busy. You know, since her husband left, she wants to do it all herself.”

Nina shakes her head. “Ay, this husband of hers should come back and take responsibility. It’s not right.”

In the haze of terror after the surgery, I’d poured it all out to Nina. How Adam, tired of his expectant wife’s “constant moaning,” refused to come home and drive her to the doctor again. How my daughter suffered in fear and pain all by herself while he was out drinking with his friends, too ashamed to call me. How he stumbled home hours later. Too late.

Suddenly, it’s Tuesday again and we’re schlepping Nina’s suitcases upstairs to her new apartment.

I help her unpack the breakables, turning away as she stands for a moment holding a photo frame, lost in a memory I’m not part of. I wonder if she’ll miss Odessa like I used to in those first difficult years.

Nina asks me to stay for a tea, but I leave.

It’s Tuesday afternoon. No one. No Rosie. No weekly ride to a clinic. I’m surrounded by nameless strangers asking to go here and there.

Then my phone rings.

“Masha?”

“Da?”

“It’s Rivky.”

My thoughts crash into each other and stall in a huge pileup.

“Ah, Rivky.”

“Masha, I’m so sorry, I really am. I should have at least called you back, but…” She trails off as I drive forward on autopilot. I wonder what I should answer.

“It’s okay,” I eventually say. “I think maybe it’s I who should not have told you certain things.”

There’s an awkward pause.

“Maybe we could talk about that, Masha. I know it’s late, and you probably have other plans. But maybe—”

Rivky pauses.

“You want I should come like every Tuesday?”

The immediate lilt in her voice lets me know I’ve made the right decision.

I make a U-turn at the next light and head toward Boro Park.

Ah, but it’s uncomfortable. Rivky settles into the back seat while I swing the wheelchair up as usual. A brief glance, then we both look away.

I’m quiet as we move out onto New Utrecht, Rivky murmuring to her child.

“I thought about you a lot this week, Masha,” she says suddenly. “And about Rosie, and about your grandson.”

I make a noncommittal sound.

“So, you told Rosie she should give her son away?”

The sequence of events should be sharper in my mind, but all I can remember is a haze of days that trickled into weeks. Days of me begging Rosie to see sense, to start living again. But she refused to see, refused to hear. Until she refused to share a single word with me, her mother who loved her more than life itself.

And then the ultimatum. That I remember.

“Mama. Benji is my son. My son! Why can’t you love him for who he is? He’s mine! If you love me, you love him!”

I couldn’t get her to see what I saw. Oh, how I loved my Rozatchka. And I knew she loved her son dearly, but at what price?

No matter what I said, it was the same thing all over again. Rosie hurling accusations at me, horrible, scathing words.

And then she told me she was moving out. It was either both of them or neither of them.

I try to gauge Rivky’s expression in the mirror. She’s listening, but I don’t know what she’s thinking.

“I don’t know what I could have done differently. But I do know that all I ever wanted was for Rosie to be happy.” My heart twinges then, as it does every time I say her name.

“I hear,” Rivky says quietly, clicking open her seat belt. We’re on Flatlands already. “We’ll talk more on the way home.”

I feel ill, my head and palms clammy. I’m so tired that I stay right there, outside the clinic, and try to doze.

We try to talk on the way home, but the conversation sputters and dies, and then Rivky is disturbed by a train of hysterically excited phone calls. After the third call, Rivky leans forward with an effervescent smile.

“Masha, my sister is getting engaged! Tonight! I’m so excited!”

I wonder what the appropriate response would be, but her phone rings once again, so I drive on.

Rivky smiles as I unload the wheelchair, fumbling in haste as she pays me.

“I’m so sorry, Masha!” in a hurried, low whisper. “I owe you a chat, but this is unexpected….”

The car seems so empty and lonelier than ever, all the cheer gone with Rivky.

My phone rings, and I glance down to reject the call.

But it’s Nina again. And if there’s anything I can do to help her adjust, to keep her from floundering like I did, I’ll do it.

“Da, Nina?”

“Masha, come back! Vika’s here! With her kids!”

I promise her I’ll come, marveling at the exclamation marks punctuating Nina’s words. Usually she’s as levelheaded as I am, but I’ve seen the sternest people become clichés when confronted with grandchildren.

I hear them before I see them. Viki, who looks the same as she always did, short and solid and placid, while two towheaded boys whoop over a toy fire truck.

We sit on fat upholstered chairs, and chat easily about Viki’s business in architecture or something, her sons squabbling in the background.

And then they’re all over Viki, yelling.

“He broke the ladder!”

“It’s mine!”

The boys cry as Nina goes in search of something else to placate them. She comes back beaming, a cheap matryoshka doll set in her hands, and the cries turn to giggles as she shows the boys how to twist open each one, the babushka and the mamatchka and the malyshka. A baby and her baby and her baby.

Suddenly I can’t take this anymore. The loneliness gapes big and deep inside me as I look pointedly at my watch and apologize profusely, but I must go, as I have an early morning job.

Such a simple thing I’m looking for, but it’s as far away as the moon.

Something about Nina’s move and seeing all her boxes makes me do something I haven’t done in years. I go to find mine.

Not that they were ever lost, but I’d placed all the things I’d never need again in Sunrise Self Storage.

I slit open a box with the key.

My textbooks. Genetics. Microbiology. Cloning. Recombinant DNA. The years when genetic engineering was exploding, when I tasted the possibilities inherent in the tiniest codes we were starting to crack. I look at the diagrams, my neat handwriting in the margins. A past Masha, one I no longer know.

The next box is a Baby Rosie box, pink blankets and a teddy. I quickly close that one.

Mama’s things. A shawl I could never bring myself to wear. Candlesticks. A sepia photo of the grandparents I never knew. Mama loved telling the same stories again and again, her religious parents and their chickens and she the only surviving child after a pogrom.

“Ay, Mama.” I don’t even realize I’ve said it aloud until the words echo around me.

I pick up our wedding picture, and the smiles rip holes in me. The cellist and the geneticist, a marriage of art and medicine.

And then we came to New York and I was a nobody, a nothing, all my degrees worthless. Barely able to make myself understood in the grocery, no way to start over. Who had money for that? Not us, a struggling young couple. And then not me as Lev went away to play for larger and larger audiences. And then not us, a single mother and her precious toddler, looking for safety and belonging.

I pull fresh tape over the boxes, sealing them tight. All the way home, I hold on tight to the key, then place it gently in the jewelry box on my bedside table.

It’s Tuesday and I’m just about to get into my car when an unexpected thought strikes me and I remember a piece of foil-wrapped cake. I lock the car again and go around the corner to the fruit store.

Asian Pear always has the most beautiful produce. I choose some fat, almost waxy oranges and carefully place six in a bag.

Their scent heady in the car, I drive to pick up Rivky.

“Hi, Masha, how was your week?”

“Okay, Rivky. And congratulations for your sister.”

Rivky looks up, surprised. The excitement of her sister’s engagement must have died down, and it’s just regular Rivky. I’m suddenly embarrassed by the oranges I bought for her.

“Thank you! Masha, last week it was busy, but I really wanted to tell you…”

I see her settling back, her child leaning against her, and listen to the story of an evening five years ago.

She doesn’t cry or hesitate, Rivky, as she tells of the ultrasound technician’s sudden silence, the doctor ordering her into an ambulance, the speeding through the streets as she frantically called her husband and mother. It’s a story I know too well, and I find myself breathing too fast as she speaks, as if by filling my own lungs deeply I can breathe in all the air those babies couldn’t get in time. The heavy citrus aroma makes me want to choke.

“But you know all this, Masha. Right? You told me the same story with your Rosie.”

“I did.”

“So tell me if it’s none of my business, Masha, because this was the part that made me upset. Why did you tell Rosie to give up her son?”

It sounds so cold, so callous, the way Rivky says it. That’s the way I told her what happened, but she’s missing all the thousands of moments leading up to it.

“Tell me, Rivky.” A thought occurs to me, a way of putting my life in context for her. “Who looks after your baby when you come with me every week?”

“Usually my mother. Sometimes my sister. Or mother-in-law.”

Ay, how to explain to a girl surrounded by family what it means to be truly alone? It was me and Rosie and Rosie and me, years of scraping together the dollars for Rosie’s college, years of driving in the mornings and cleaning homes in the afternoons with an obedient Rosie in tow. How do you put in words the pride you have to swallow to call your child’s father to beg for money? But every bit of that swallowed pride worth the pride to come as she rises bright like a star.

And then the way it all tumbled down, a Jenga tower collapsing in on itself.

I try anyway, putting the words down carefully.

Rivky is silent as I finish, the clinic coming into sight up ahead. I feel the disapproval, know she still doesn’t understand. I so badly need her to see it. I make a last desperate attempt.

“Rivky. You care for your child with all your heart and soul, I know you do. You do all this for her sake because you love her, right?”

I twist my body to look back at Rivky. Her eyes flash as she pulls her daughter closer.

“Yes.”

I look straight back at her.

“So did I, Rivky. So did I.”

I find a parking spot and let the engine idle. None of us moves for an endless minute until Rivky sighs and leans over to maneuver her child out of the car.

“Thank you for sharing, Masha,” Rivky says quietly. “We’ll have to pick up here when we get back.”

I’m debating where to go for the next hour when my phone rings. I glance down.

Rosie.

I do the same thing that I’ve been doing for the last 18 months and tap my thumb gently on reject.

You would think it would get easier, week after week after week. But it doesn’t.

An hour later, we’re on the way home, inching slowly along a congested Avenue M.

I see Rivky looking out of the window as she talks, glad she’s not looking at me, can’t see what I’ve done.

“See, people make all these assumptions about you. If you’re smiling, you’re taking things so well. If you’re sad, maybe it’s too much for you. If you’re happy it’s because your family is taking such good care of you, and if you’re upset, someone must have said something hurtful.

“But Masha.” She turns back to face the mirror and I focus intently on the tailgate of the Honda in front of me.

“Having a special child means all of it. It means sometimes you’re fine and sometimes you want to give up. It means banging your head against the wall to blunt the pain of it, it means being so grateful for the smallest of blessings like the first time you hear mommy. It means facing a new day every day and believing you can make it. I believe in a G-d and His plan, you know.”

I think of saying something about Mama and her candlesticks then, but I don’t want this conversation to go off on a tangent, so I keep quiet.

“I can’t tell you I’m always so good.”

I cough. Talking seems painful, as if I’ve suddenly forgotten how.

“But look at you every week, Rivky. Here you go, all the way to Marine Park and back, again and again.”

She laughs dryly.

“Just because I’m here doesn’t mean I’m always happy about it. It means it’s something I need to do. Something I’ve chosen to do. Some weeks I’m sure I’m wasting my time, and some weeks I am happy, knowing I’m giving my daughter a better chance at walking.”

I almost interrupt, but the question sits deep where I’ve learned to store the things that must remain unspoken. What if your love comes at a price someone else has to pay?

“Life is about choices. We choose how to play the hand we’re dealt.”

Suddenly Rivky leans forward.

“I don’t know how to say this, Masha. But you needed to let Rosie figure all this out for herself instead of forcing her to agree with your choices. I understand why you thought that your way was the right way. But it doesn’t work like that.” She leans back again.

“Please don’t be angry with me,” she says in a small voice. “I’m only trying to explain to you why Rosie might not want to talk to you. Maybe she feels like you didn’t give her a chance to love her child, to give him the best life can offer him, just like you did for her.”

The shame makes my skin prickle.

“Ah no, I’m not angry, Rivky.”

“Some days I don’t want to get out of bed.” Her voice has turned low. “But then I think of the people I’m failing, most of all myself. And I know that part of acceptance is just taking that first step. Getting up and getting dressed and putting a brave face on.”

I swallow hard. I know about putting a brave face on. About getting out of bed even when you don’t want to. But that was when I had a good reason to, when the dream of Rosie’s future was in reach.

“You’re a brave woman, Rivky,” I say, turning off the engine and snatching up the oranges before I lose my nerve. “Please take these, they’re for you.”

She smiles at me as she takes them, eyes damp.

“Thank you, Masha. I hope I didn’t upset you.”

The guilt feels like a layer of dirt caking my soul, my chest so heavy I can barely breathe.

I didn’t know Rosie wouldn’t come back. Let her move out, I thought, and she’ll be back in a week, two weeks, telling me how right I was. Telling me she needed to concentrate on becoming a pediatrician. Telling me no disabled child, no matter how much she loved him, was going to hold her back.

I never meant to throw her out. Never, in a thousand million years. Never. But the days turned into weeks and she didn’t come back, didn’t come to her senses. And by then the guilt and shame and anger had piled on so deep that I couldn’t dig myself out from under the mess I’d made. Couldn’t find a way to explain to my Rozatchka that her mama loved her more than life itself, wanted to protect her from a life of pain, and would do anything to have her back.

And still she called, and still I couldn’t find the words.

Three blocks away from home the engine starts making a horrible grinding noise. I nose my way gently to the side of the road, thankful for the slow movement of the cars around me as my car sputters once, twice, and dies.

I’m rootless, unmoored. No car.

For two days I walk around aimlessly. Bruno at the garage said I can’t afford to fix my car, that I shouldn’t spend so much on a repair that won’t last.

But I can’t afford not to fix it either. What am I going to do?

I spend one morning with Nina, bringing her rassolnik and borscht, although she’s more efficient than I am in the kitchen. She’s so settled, taking her grandsons to the park, nodding to people she can’t have known for more than a week or two. She doesn’t need me.

When I sleep, I dream restlessly of nothing — empty spaces, endless corridors, labyrinthine mazes where I wander blindly.

I need a car.

I look at secondhand cars, none of them mine — an old taxi with thousands of miles on its odometer, the mileage of my life in its scarred leathered seats.

On Sunday it suddenly dawns on me that I have to let Rivky know that I won’t be able to take her on Tuesday.

I gave her my number all those weeks ago, but I don’t have hers.

Ay, no.

I scroll down, down — maybe it’s somewhere in my call log. She called me once, but there’s no way I can find it.

I don’t know anything about Rivky, really. I know where she lives. I know that she’s a dedicated mother to two children. I know where she takes her child every Tuesday.

Not enough.

I wrestle with this problem until Monday afternoon. And then I make my way onto a bus.

I can’t let myself think, as I ring the bell at a door I’ve never even looked at. The nameplate says Family Bran-something — I don’t catch it all before it disappears inward to reveal a young turbaned woman with a toddler on her hip. I think I may have made a mistake.

“Masha?!”

It is Rivky. Her voice, definitely.

“What — what are you doing here? Is everything okay?”

You miss so much when you’re looking backward. Her eyes are the only things I would recognize.

I shake myself out of my stare.

“Ah, Rivky. I’m so sorry. I came to tell you that my car broke down. I can’t take you on Tuesday, I don’t know when I can fix it.”

She looks at me, startled. Then she cranes her neck to look behind me, as if suddenly computing what I’ve just said.

“Wait. Your car broke down? So how did you get here? Oh, Masha, come in.”

That’s how I find myself in a neat little kitchen holding a tea, wondering how I got here, wondering how I can get out again.

“I think it’s a sign, your car breaking down, Masha.” Rivky is her chatty self, bustling about, slicing cake. Her toddler sits placidly near her, gnawing on a cookie.

“I mean, not for you! It must be horrible! For me, I’ve been thinking about stopping our weekly visits to the clinic. I can’t see any progress, I think it’s a waste of time and money.”

I don’t know why this upsets me so much.

“Please don’t say that, Rivky!”

Her eyes widen. “Say what?”

“Don’t stop your sessions. Please, you don’t know if this week or next week your child will suddenly turn a corner. Don’t give up because of my car!”

The silence is excruciating, heat spreading up from my chest to my face as I search for a good way — any way — to end this.

“Masha?” Rivky finally says. “I know you mean well, the very best. Who else would come all the way to Boro Park to cancel a commitment?”

And then she puts a finger on my arm with the lightest of butterfly touches.

“You can’t fix my life, Masha. I know you want to.” She takes her hand back; somehow I can still feel it. “But like I said, it’s my life, my choices, my mistakes.”

Then gently, “Find Rosie, Masha. You have a lot to tell her.”

I look at Rivky, this girl who came charging up a street and into my life one Tuesday afternoon, and find nothing to say.

“Maybe call me,” I mumble at the door, and she smiles and waves and promises she will.

I look at the box I brought home with me from the storage facility. Almost since the beginning of time, we’ve known that humans are made up of matter. But we’ve only known the secrets about what makes them matter for barely 150 years. Sitting here, pulling out old useless textbooks, I wonder how different everything would have been had I stayed in that world. Would I have discovered the secret of who I am, who I could be, by digging through strings of code? Look at me now. Far from anything I ever dreamed of being, and yet my genes haven’t changed since I moved, became a mother, a taxi driver, a nobody.

Rosie’s son. No mutation in his DNA and yet a victim of circumstances beyond anyone’s control. I think of Rivky. Of Adam. Of choices and mistakes and responsibility.

“But what can I do?” I direct at no one, Mama’s picture on the mantlepiece making me cringe. “Da, I could have said it differently. I should have done things differently. But it’s too late, I don’t know… ay.”

Too much time alone and I suddenly have a memory of Mama telling me what her papa used to say. You do yours and He — a finger pointed upward — will do the rest.

I drag the box to the garbage and walk down the street, wondering how long it will take me. I must have driven this route hundreds of times, never noticing things like the salons and laundromats that even now I barely register.

My thoughts are in the past, remembering how we chose rugs and curtains, excitedly set up the rocking chair and the crib. Rosie and I wandering up and down aisles and buying more and more baby paraphernalia, Adam fondly exasperated as he came home to more shopping bags and a happily exhausted wife. We’d often eat supper together, all Rosie’s favorite foods that I’d cooked to keep her strength up.

My chest tightens as I turn into the familiar block, as familiar as my own. I still don’t know what I’m going to say. With all the words available to the human race, we can’t always find the right ones. Sorry is meaningless.

I walk past the building, a coward.

Maybe, Mama, some things are just not meant to be.

ItÕs like a crack has opened up for me, a crack where I can glimpse some kind of reconciliation, a meeting of our hearts if not our minds. But every time I tap contacts and pull up Rosie, my finger hovers over the options until the screen goes dark. I can’t seem to gather the courage to call her. Even sending a text seems beyond me.

All night I struggle, sleep eluding me.

Morning comes and I get dressed, the grit of sleeplessness making my eyes burn. One step, Masha. One step. Rivky’s voice, Mama’s voice, my own voice. Call Rosie.

I want to. And still, I can’t.

I leave in the direction of the public library, hoping to find something there to distract myself. Nothing piques my interest. Instead, I watch a Mother and Baby Reading Hour circle, mothers and toddlers on huge poufs and little purple chairs, remembering how I struggled with English rhymes for Rosie. I pick up two novels — not my usual fare, but nothing about these last weeks has been usual — and check them out.

I have three missed calls from Nina when I come out.

“Masha?”

“Da, Nina, izvini, my phone was on silent.”

“Ah! Are you near home? I decided to come to see how you’re doing.”

I tell her I’ll be there in 15 minutes and hurry home, puzzled. We don’t yet just drop in to visit each other at whim. I hope Nina hasn’t picked up on how unsettled I’ve been recently. I don’t need anyone’s pity — tomorrow I will get a secondhand car, no matter what.

I climb slowly up to my apartment, phoning Nina to see where she is but I hear Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance floating down to me. She’s already at my front door.

My keys are in my hand when I get to the last step.

“Nina?”

She’s standing there with a stroller. And someone with a thick blonde braid and the most beautiful face in the world.

The books and the keys and my handbag crash to the floor and then it’s just me, hands pressed to my chest, Rosie disappearing behind a veil of tears.

Sometimes people don’t know what they’re looking for.

And sometimes, people don’t even know that they’re looking for something.

Nina wasn’t looking for Rosie, but she met her in a supermarket, just like that. Ah, she’s nobody’s fool, my friend Nina; she was wise enough to bide her time.

I look at the golden child in Rosie’s arms and wonder if things can ever be repaired.

I think of Rivky and her child. Rosie’s boy peeks cautiously at me before beaming guilelessly, a little person already — toy in his hand, braces on his feet.

She smiles at me, luminous, and I think about the journey we still have to take as Nina leaves quietly.

I dig deep to find words.

“I’m so sorry, Rosie. Rozatchka. I—”Ay, I can’t do it. All I can do is sit next to her on the same couch she lay on as I nursed her through stomach bugs and strep throats, the same couch we sat on as I read her stories and looked over her assignments, my hand on her back now while she talks quietly, telling me her story — the one I’m finally ready to hear.

The shame rises again as Rosie opens the door to let Adam in — her husband who came back to face the things he ran away from, who takes care of them both with the devotion I thought he was incapable of. The one who takes their son to a special day-care program, to therapy. The one who encouraged Rosie to go back to her residency, who took responsibility.

I say nothing as I see the small knitted circle on his head, thinking Mama would have smiled. And Rivky.

Life is about making choices.

And by making them, we make mistakes. We’re human — sentient beings so much more than molecules and polynucleotide chains. And so, we need to live with our mistakes.

I hope we can find forgiveness. And acceptance.

Finally able to trust my legs to hold me up, I go to the kitchen to bring out some drinks. I put some pitchenya in the oven for ten minutes, grateful for my full freezer.

Everyone is looking for something, I think, sitting down again next to Rosie.

Most people spend their lives looking for an elusive happiness.

But as I take Benji into my arms, I know that mine is right here.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 789)

Oops! We could not locate your form.