The Principle of the Matter

| March 22, 2022The clock is ticking for Zeidy — should we bend our principles?

Pinchos: Doesn’t your grandfather come before your principles?

Shaya: We’re adults, and we’ve chosen a different path in life.

Pinchos

When a loved one is in the hospital, your routine is just different.

My father wasn’t young, and we’ve had minor scares and medical crises over the years. Now, though, his health was deteriorating rapidly. He was suffering from kidney failure and on dialysis while we frantically searched for a donor. And for the past few weeks, he’d been suffering from recurring fevers whose source the doctors couldn’t identify. He’d been in the hospital for several weeks already, and things were stable, but the situation wasn’t encouraging at all.

My sister and I both live nearby, and we each visited daily. I’d come straight from work, stay for a few hours, sometimes overnight if things weren’t looking good. Chassi came around midday and spent the afternoon there. My wife, Raizy, took shifts every so often, and the children and grandchildren visited when they could — which was revitalizing to my father. He lived for these visits, the company, the interaction, and especially, the eineklach.

It was heartbreaking to see him like this, so fragile, so dependent. On the one hand, the fact that he was still completely focused and aware — his mind clear, his speech fluent — was a tremendous brachah. On the other hand, he was frustrated, bored, and lonely. I felt helpless watching him clinging to the vestiges of his dignity while losing his physical abilities. What could I do, though? But I was determined to do whatever I could to keep up his morale, to keep visiting, to learn with him whenever he felt up to it, and to try to ensure a steady flow of other visitors.

As the weeks went on, it became harder. As much as he tried to shield me from it, Tatty was feeling low. The only time I saw him smile a real smile was when my grandchildren — his great-grandchildren — came to visit.

He was like a different person during these visits. He’d schmooze with them, quiz them on what they were learning, and crack jokes. The younger ones drew him pictures, the older ones prepared divrei Torah, and he would distribute candies from the dish beside his bed and beam with pleasure at their offerings.

We have three married children living nearby; Chassi has four. When we told them how much it meant to Zeidy to have his great-grandchildren come to visit, they really made an effort to come as often as possible. Of course only the local ones could come, but my daughter Sheva, who lived out of town, Skyped in once a week with her crew, and Chassi’s Moshe did the same before Shabbos, waving his pudgy toddler’s fist at the camera and coaxing him to smile at Zeidy.

Then Mindy came up with an idea.

Mindy’s my oldest, and a real powerhouse. Whenever she came to visit, her kids had an entire program planned: skits, songs, costumes, the works. My father loved it.

But Mindy wanted to do more. She’s the oldest grandchild, and had always been close to my parents.

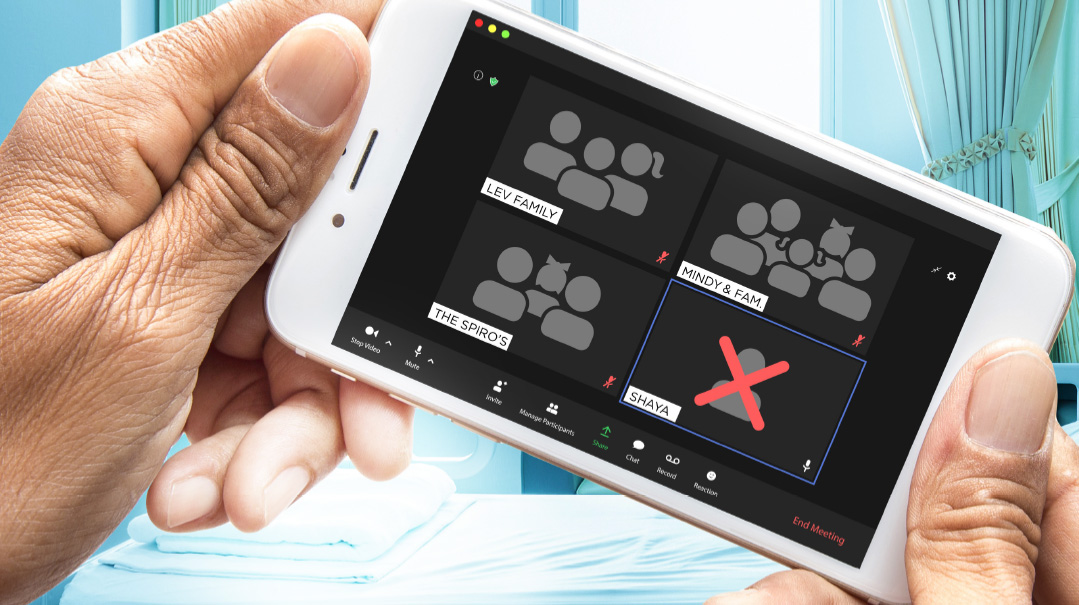

“Zeidy’s so good with kids,” she told me. “They love going to see him, but visiting hours are so short. Zeidy’s so lonely the rest of the time. How about we do a Zoom conference call every week, for all the grandchildren to join? Zeidy could tell them a story — they’d love it — and then everyone could have a turn to share some news or a message, something like that. And that way, all the kids could join, even the ones out of town.”

I thought it was a great idea. Besides Sheva, I had another three married children who didn’t live locally, and this way their kids could join, too. And having an organized Zoom call scheduled would give Tatty a sense of anticipation and purpose. He could prepare a story to tell, and knowing him, he’d want to get some props and prizes involved as well.

This could be a game-changer.

My father loved the idea, although it took me some time to convince him that the kids themselves wanted and requested it. He didn’t want to be a burden on anyone. But when he saw how excited the children were at the idea, he agreed immediately.

The first session was a huge success. Ten families signed onto the Zoom call, with a total of nearly 40 great-grandchildren. My father seemed to draw new energy just from looking at the screen. He’d prepared a short story and then a fun quiz, awarding points to the grandchildren who were able to answer correctly. By the end of the hour, my father was satisfied and exhausted. It was the first time in weeks that he’d looked so accomplished, so fulfilled.

I called Mindy on my way home.

“Great idea, really great,” I told her. “You should have seen how happy Zeidy was, it literally made his day. Thank you for organizing it.”

“It was nothing,” Mindy said. “I’m really happy it worked out, Ta. I just wish I could do more. We all care about Zeidy so much.”

The weeks went by with not much change. Tatty kept on having fevers, and the hospital didn’t want to release him like this. The extended hospital stay was taking its toll on all of us, but the Zoom session with the great-grandchildren remained the highlight of Tatty’s week. We’d decided to keep it to once a week, to keep the excitement all around. And more often would also be too much for the parents, who had to get the kids set up, supervise the sessions, and schedule the evening around it.

One day, at the end of a call, my father asked to see the younger kids. Generally, it was only the school-aged grandchildren who joined the story sessions, but my father missed seeing “his babies.”

“Sure, Zeidy,” Mindy said immediately, holding up a pudgy Chaim to wave at the camera. Devora, Sheva, and the others brought their littlest ones on screen too, taking turns to wave hello and coaxing out smiles.

My father was beaming, drinking in the nachas. He was getting progressively weaker, but this gave him strength.

When we were done, though, he looked a little perturbed.

“Is something the matter, Tatty?” I asked, closing the laptop and stowing it safely away until next time.

My father frowned. “I was just thinking… you know who I haven’t seen in a long time? Shaya’s little one, he must be getting big by now…”

My son Shaya lived in Eretz Yisrael. He and Chavi have one little boy, Yossi. But they would never do a Zoom call. I don’t think they even had email addresses.

“I have pictures of Yossi on my phone,” I said, showing him them the most recent ones I had — the ones Raizy took over Succos, when they’d last flown in for a visit. “He’s older by now, but these are still nice…”

Honestly, it didn’t bother me that I didn’t receive daily photo updates of our little grandchild. It bothered Raizy more. But Shaya and Chavi didn’t have smartphones, or WhatsApp, or anything like that; they took photos on an old-fashioned digital camera and printed them every six months. We’d see them eventually, and baruch Hashem, they were happy. Wasn’t that the main thing?

My father looked carefully at the pictures, but compared to in-person visits or even seeing the other kids over Zoom, it wasn’t the same. I wondered if I should call Shaya, ask him to take Yossi round to a friend’s house to say hello to Zeidy. But they were so adamant about not using the Internet, I wasn’t sure if it was worth the energy.

A few days later, Raizy handed me an envelope.

“Someone dropped this off — a friend of Shaya’s who came back for a wedding,” she explained. “They sent a card for Zeidy, and some updated photos.”

“Cute,” I said, fingering the envelope. It felt more meaningful than a dashed-off text message with an attached file of pictures. Shaya had really taken the time to prepare something for Zeidy, and I was touched.

I brought the pictures to my father later that day.

“Look at this!” I told him. “Shaya and Chavi sent these pictures… and a card from Yossi, see, he colored it himself…”

My father smiled as he took the envelope, looked through the pictures, nodding. “Very nice, very nice,” he said.

“Should I put them by your bed? Hang them up?” I offered.

My father shrugged. “Fine, thank you.” Then he paused. “I just — it would be so nice to see them for real,” he said wistfully.

The next time I spoke to Shaya, I decided to sound him out.

“Zeidy really appreciated what you sent,” I said casually. “You know how much family means to him, how important it is to him to have a relationship with the grandchildren and the great-grandchildren…”

“Of course,” Shaya said. “If we didn’t live so far away, we’d be visiting every week. I wish we could.”

“I know,” I said. Then I cleared my throat. “You know what Mindy’s organized here, a Zoom session for the grandchildren each week? Zeidy loves it, telling them stories, making quizzes…”

Shaya’s voice is suddenly guarded. “Yes, she told me.”

This wasn’t going to be easy. “So… it’s really for the school-aged kids, but the younger ones, the babies, they usually come on at the end to say hello. Zeidy loves it, it means the world to him.” I paused, hoping he’d offer to join. Even just once. But he didn’t.

“I know the timing might not work out for you in Eretz Yisrael, but maybe, you know, we could arrange… Zeidy would love to see Yossi, even just one time.”

Shaya’s voice was strained. “Ta, we don’t even have a computer, we can’t do Zoom calls.”

“I know that,” I said. “But maybe you have a friend who has one… you could schedule a visit… I’ll make sure someone can set Zeidy’s laptop up at the right time, we’ll work around your schedule.”

Shaya was quiet for a minute. “Look, Ta,” he said finally. “It’s not that — it’s our lifestyle, our values… Chavi and I don’t want Yossi in front of a screen, period. No matter whose or where it is. My kollel doesn’t allow Internet usage, our community is very makpid… it’s not a boundary we’re willing to break. I’m sorry.”

“Mr. Isaacs? Can I speak with you, please?”

The doctor looked stern. I followed him out of the ward, into a private room.

“I wanted to discuss your father’s care. He hasn’t been doing so well.”

“The fevers?” Despite all the tests the doctors had run, they still couldn’t figure out the source of his recurring fevers.

“The fevers too,” the doctor said, “but also in general. His kidneys are continuing to deteriorate, and although we’re doing our best, the situation isn’t looking good.” His face was grave. “We can discuss options for his care, but I need to be honest with you — the choices are limited. I’m not sure that a transplant would even be viable now.”

I stood up, feeling shaky. “Can we discuss it when my sister’s here? We’ll make any decisions together.”

“Of course.” The doctor nodded briskly, we scheduled a time to meet, and I went back to my father, feeling suddenly old.

I knew Tatty wasn’t doing well, but it hurt to have it spelled out like this. Deep inside, I’d still harbored hope that he’d get better and come home. He was putting up a good fight, but as I watched his chest move up and down as he slept — he was sleeping more and more recently — I wondered dismally what would be.

Sheva came in to visit for a few days with her family. They stayed with us for Shabbos and visited Zeidy several times. The grandchildren who lived local came often as well.

“It’s not just for Zeidy, it’s for us, too,” Mindy told me. “We want — our kids want — to spend as much time as possible with Zeidy…”

She trailed off, but I knew what she wanted to say: Before it’s too late.

The ones who couldn’t travel scheduled Zoom sessions, to talk to Zeidy, make him smile, show him the kids’ projects, give him nachas. Seeing the great-grandchildren was my father’s life support; giving him the strength to smile even when he could no longer sit up comfortably.

Shaya didn’t forget about Zeidy. Ever dutiful, he phoned often, at least once a week, putting the phone on loudspeaker and coaxing Yossi to babble into it. He and Chavi chatted about life in Eretz Yisrael, about Yossi’s latest antics, about what Shaya was learning. They did their best. But I could tell my father wanted more.

“I just want to see him,” he sighed to me once, when we got off the phone. “Give him a brachah…”

Say goodbye.

Shaya and his family would be coming for Pesach — it was only a couple of months away — but who knew what would be by then?

I bit my lip.

I wanted to be proud of Shaya, the way he had such strong Torah values… but it hurt to know that my father was in pain because of him.

Raizy didn’t even think there was anything to be proud of.

“Torah values?” she asked, a thread of mockery in her tone. “Where in the Aseres Hadibros does it say You shall not use Zoom? But, oh, kibbud av v’eim — which by the way, it does say in the Aseres Hadibros — he doesn’t care about?”

“Of course he cares,” I said. “He does his best. He phones, he sends pictures… but this is a decision he’s made for his family. And it is an important value to have. Maybe Zoom isn’t so bad, but free Internet usage certainly can be very destructive. You don’t hear where he’s coming from?”

“I do, but he’s in the wrong,” Raizy said firmly. “We’re not asking him to use the Internet freely, or even to use the Internet at all. Just to go to someone’s house and speak to his grandfather, who is deathly ill, for ten minutes. Ten minutes! Mindy found him somewhere, a friend of hers, she’ll set everything up. He won’t have to touch the computer, won’t have to do a single thing except show up on the screen.” She was talking fast, furious. “And he just won’t do it. Not for us, not for Zeidy. How is that right?”

I’ve always prided myself on being fair and reasonable, not one of those people who bash others’ standards just because they’re higher than my own. But here, I knew deep down, Raizy was right.

“We’ve raised him to uphold his principles, let’s just be proud of it, let’s not fight,” I said weakly. “He’s got good values, baruch Hashem for that…”

But when I thought of my father, slipping away in the hospital with his wish to see all his eineklach unfulfilled, I wondered: At what price?

If I could tell Shaya one thing, it would be: How can you allow your stringencies to come at the expense of your grandfather’s dying request?

Shaya

I knew it wouldn’t be easy to take on standards that are different from the rest of my family’s.

It’s not that I have it so terribly hard, either. Chas v’shalom! My parents raised me in a frum, Torahdig home. I had a great yeshivah education. And they’re contributing toward our support in kollel now, as well.

I don’t have to fight for Shabbos, for kashrus, nothing like that.

It’s just the technology.

A great, big, “just.”

I grew up in a typical American community, and my sisters all have smartphones and computers with Internet. I always knew I didn’t want a lifestyle like that; I don’t believe in using screens as babysitters, and always cringed at the sight of my nieces and nephews plastered to some phone or computer, watching whatever movie or clip. It wasn’t the content, necessarily, it was more the hashkafah; using a screen as entertainment.

My wife, Chavi, agreed with me 100 percent. “Screen time turns kids’ brains to mush,” she declared. “They don’t learn to think, to play, to use their imagination. It’s just not healthy for their development.”

And that, of course, was besides the host of spiritual dangers inherent in Internet usage. There were so many horror stories, so many things that could go wrong even with the best of intentions and the safest of filters. We were determined to set up a home that would be sheltered from all of that, and we’ve never regretted that decision.

Chavi works as a gannenet and I’m in kollel. The community we belong to is very stringent about technology usage; in fact, to join the kollel, I had to sign that neither my wife nor I would be using Internet. Our friends and neighbors were like-minded, and we felt privileged not to have connection with the shmutz of the outside world.

When Yossi was born, we were determined to keep to a no-screen policy.

“Why should a baby know what a screen looks like?” Chavi asked, and I agreed.

Besides, the cheder we were planning to send him to wouldn’t allow him to have access to smartphones or computers.

The challenges started when we went back to America for Yom Tov.

Chavi’s family is less technology-minded than mine. They have a computer in the study, but my parents-in-law both have dumb phones, and Chavi’s siblings are all younger. Staying there wasn’t an issue. When it came to my family, though, we had a problem. My family all use smartphones. I was uncomfortable with the idea of Yossi, at close to a year old, being exposed to that, but I figured that my parents weren’t the type to shove it in his face, and besides, so much of the time was Shabbos and Yom Tov, in any case.

I didn’t bank on my sisters getting so worked up about the issue.

“What’s this about not looking at anything on a screen?” my sister Mindy demanded. “I’m trying to show Chavi these adorable rompers on Ali Express, and she’s all like no, no, I’m holding the baby, we don’t let him look at screens. Come on, seriously?”

I bit my lip. Mindy’s the oldest sister, and pretty tough. Chavi’s gentle and sweet and easily intimidated by forceful personalities — not that she would bend her principles, but she was probably upset. Yikes, I’d have to do damage control.

I shrugged and reiterated to Mindy that we weren’t comfortable with screens or Internet, not matter what the content — and went to find my wife.

But it wasn’t just the outright questions or barbs, it was also the culture — the all-pervasive Internet and technology culture so prevalent in my parents’ home.

Motzaei Yom Tov, I came home from Maariv to find all the kids crowded around my sister Esti, watching something on her phone. Yossi was there too, tugging at her knees. It was some stupid clip with animated cartoons, but I was still angry. Now he was just a baby, but what about in one year, two years’ time? How would we shelter him from this culture, from the bad language and unsavory images that constantly jumped out from even the “innocent” clips, if his aunts and cousins were always shoving it in his face?

I tried speaking to Esti and the others, but they wouldn’t hear me out.

“It’s nothing against you, it’s just that we’re so, so careful with what he’s exposed to,” I said earnestly, hoping Esti would understand. She was quieter than Mindy, a listener.

But Esti didn’t get it. “He’s a baby,” she said. “Are you serious that you think seeing our kids watch something on a phone will damage him for life?”

“That’s the whole problem, that’s where it all starts,” I said. “You think it’s just a baby, just one clip, and before you know it, it’s a toddler watching movies for entertainment, unable to stimulate himself. Better not to start with screens at all.”

Esti looked insulted, and too late, I remembered that her two-year-old sat watching Uncle Moishy for close to three hours on Erev Yom Tov afternoon. She’d been delighted — it kept him quiet and entertained.

“Not everything needs to be so black-and-white, you know,” she said stiffly. “You don’t need to say a blanket no to everything in order to protect your kids. Maybe now it’s easy, you have one baby, but just wait till you have a family, and their friends watch stuff, and you’ll see, it’s not so simple as all that. Much better to say yes to some things and save the no for the really problematic stuff.”

“That’s not really the point,” I said. I hadn’t started this conversation to get into a chinuch debate with my sister. “All I want to say is, please don’t show videos and things when my child is around.”

“Look, you can’t expect us to start checking where Yossi is before we use our phones,” Esti said, annoyed. “Maybe if you don’t like what we do here, you shouldn’t come visit. But if you’re here, can’t you go along with the majority?”

“Not l’ra,” I muttered. “Listen, Esti, this is something we really care about, and we would appreciate if you wouldn’t put it down, and just tried to accommodate. We respect what you do, we don’t interfere, so we’re just asking for you to do the same for us.”

I was happy with how that sounded. I’d have to try the same speech with Mindy and the others.

Esti didn’t seem to take it too well though. “Respect? You call it respect to start nitpicking on what we do or don’t do with our phones? I’m sorry, but I don’t think so.”

She stalked out of the room.

I bit my lip. This wasn’t going to be easy.

But then I remembered why Chavi and I were doing this, and strengthened my resolve. It was worth it.

And then Zeidy was hospitalized.

I made sure to call my parents for updates — often. I wasn’t on the family WhatsApp chat, so I couldn’t get the news that way. And of course, I davened for him every day. I even asked the entire kollel to dedicate a seder in his zechus. My father was touched to hear that.

I tried to call Zeidy, too, but it wasn’t so easy. The timing was difficult: We were seven hours ahead in Eretz Yisrael, and bein hasdarim was too early to call. I tried to phone in the evening, but sometimes Zeidy was sleeping, or too exhausted to speak, or had other visitors. Still, he knew I was trying, that was the main thing.

At one point, I thought of starting a chavrusa with Zeidy. He loved to learn, and I figured it would brighten his day to have a regular chavrusashaft. My father loved the idea, and we figured out a time that would work, two or three times a week.

I could tell Zeidy was enjoying the learning sessions. We’d get on the phone, schmooze a few minutes, Chavi would say hello and Yossi would babble into the phone to give Zeidy some nachas. And then we’d dive into the learning for as long as Zeidy was able, or until I had to leave for Maariv and evening seder.

One day, when I called, Zeidy sounded extra enthusiastic.

“Wow, Zeidy, you’re excited to learn today,” I joked.

Zeidy chuckled. “Always. But actually, there’s something else I’m excited for. Your sister, Mindel, she’s a real tzadeikes. Thinking of her elderly grandfather…”

“We all think of you all the time, Zeidy,” I said automatically.

“Of course you do, of course. I was just saying that Mindel’s had an idea… she’s getting all the grandchildren to come together on one of these Zoom shmoom meetings, ich veis, and we’re going to learn the parshah together. Won’t that be nice, all the eineklach coming on together?”

All the eineklach. Zeidy’s dream. And of course, there was no way for everyone to visit at once right now.

“I’m — so happy for you, Zeidy,” I managed. “It sounds like it will be amazing.”

But there was a pit in stomach even as I spoke. Mindy and Zoom. We were going to run into trouble.

I wasn’t wrong. It wasn’t long before Mindy started calling, harassing us about joining the Zoom calls to give Zeidy nachas.

First, we figured the time difference was a good enough excuse — the calls were scheduled for early evening, US time, well past Yossi’s bedtime. But then Mindy changed tracks.

“Look, I get it, you can’t join the calls because of the time difference,” she said, with an air of someone who’s about to solve all your problems. “But I figured, better for Zeidy to at least have a chance to see you guys, even if it’s not at the same time as everyone else. He really, really wants to — it would mean the world to him.”

I rolled my eyes. Yeah, right. Zeidy had always been happy with the phone, with pictures, with the good old-fashioned ways of staying in touch and showing you cared. He wanted to use Zoom like I wanted to fly a helicopter. This was a total set-up planned by my sisters, who seemed to be on a campaign to force me to give up on my standards.

“I know you don’t have Internet, or even a computer,” Mindy continued. “And you probably wouldn’t know how to find Zoom even if you had one. So I’ve figured it all out. I have a friend who lives in your neighborhood, she has a computer — with a filter, of course — and she’ll be happy to host you any evening you like to go on Zoom and give your grandfather some nachas.”

I tensed. Mindy’s whole manner was so domineering. She spoke with such finality, like she was presenting us with the instructions and that was that.

I looked at Chavi — we had the phone on loudspeaker — and she shook her head firmly. No way.

“Mindy, you know we can’t do that,” I said, trying to sound both patient and assertive at the same time. “We have a no-screen policy, and we’ve signed an agreement with the kollel. We don’t use Internet. Not in other people’s houses, not ever. But we call Zeidy all the time, we sent him a card and pictures…”

“He doesn’t want cards, he wants to see you,” Mindy cut in.

I sighed. “Listen, let’s just pretend Zoom doesn’t exist, okay?” I said. “If there were no such thing as video calls, then Zeidy would be totally fine with phone and letters.”

“But it does exist, and Zeidy’s getting hurt,” Mindy said pointedly.

“Why, because you’re all reminding him about the fact that we’re not coming on?” I was getting sick of this. “For us, the option doesn’t exist, that’s all.”

I hung up, finally, and looked at Chavi. She looked as disturbed as I felt. She thought the whole thing was just a ploy — my sisters were insecure about our standards and trying to get us to break them.

“We’re not comfortable using Zoom and they keep pressuring us, it’s not fair,” she said, agitated. “We do so much for Zeidy, much more than they do with their screens and their WhatsApp — it takes time to handwrite cards and go to print photos from an SD card. If they’re so desperate for Zeidy to see us, they can pay for us to fly back and we’ll go see him in person. But we’re not using Internet devices or exposing Yossi to screens and technology just to make Mindy happy.”

I was in full agreement. Besides, I could see where this was going. We’d give in now, and then we’d be pushed to give in again and again. For my parents’ upcoming anniversary, for someone’s bar mitzvah, for whatever occasion… there would always be a reason we’d “need” to break our commitment and go use Zoom in someone’s house. If we gave in once, our firm standards would be a thing of the past.

The only one I really felt sorry for was Ta. He didn’t exert any pressure, but he really sounded sad when he asked if we’d rethink our decision.

“It’s the one thing Zeidy keeps asking for, to see his great-grandchildren,” my father said. “The picture you sent was nice, but it’s not the same. Can’t you work it out just this time?”

I swallowed. “I’m sorry, Ta,” I said. “But we’ve discussed this, Chavi and I. We really can’t.”

If I could tell Tatty one thing, it would be: We care about Zeidy very much, but it isn’t my sister’s job to tell us what to do.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 904)

Oops! We could not locate your form.