Zeidy’s Legacy — Tomchei Shabbos

| January 18, 2022My zeidy, Reb Yehoshua Tzvi Hershkowitz, founded the very first Tomchei Shabbos more than 40 years ago

As told to Sandy Eller

When you hear the words “Tomchei Shabbos,” you probably think of community-minded people getting together to pack groceries for those going through hard times. Or you might even envision drivers making their way through local streets, discreetly dropping off boxes of food to those who are having difficulty paying their food bills.

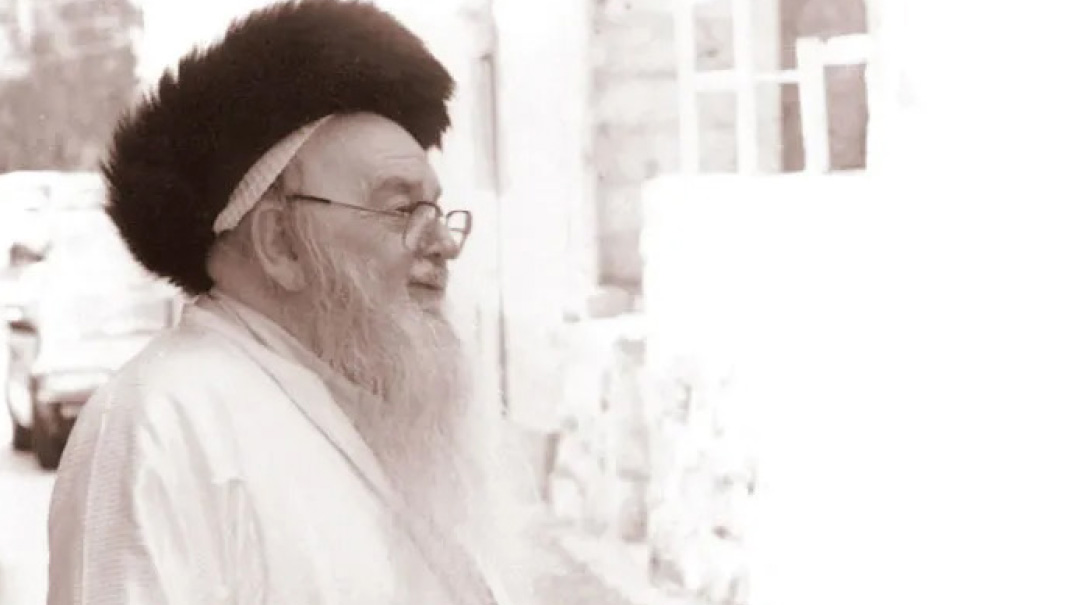

Me? When I think of Tomchei Shabbos, the image that pops into my head is that of my zeidy, Reb Yehoshua Tzvi Hershkowitz, who founded the very first Tomchei Shabbos more than 40 years ago.

Zeidy was quiet and unassuming and he truly lived to help others. Not only did he never seek the limelight, but Zeidy worked very hard to stay as far away from it as possible. He kept his Tomchei Shabbos efforts under the radar during his lifetime, but having recently marked his fourth yahrtzeit on the 7th of Teves, I think the time has come to share his story, and hopefully bring his neshamah an aliyah.

Zeidy was born in a Hungarian town so small only three families lived there — but that didn’t spare it from being hit hard by the war. It’s true that Hungarian Jews experienced the horrors of the Holocaust for a shorter period than many others, but Zeidy was forever scarred by the unimaginable suffering he saw during his time in Dachau. He promised himself that if by some miracle he managed to survive the atrocities of World War II, he would make sure no one ever felt the pain of hunger that he experienced during that dark time.

With the Eibeshter’s help, Zeidy managed to get through the war, but his return to his hometown was devastating. His parents, his two brothers, and his sister were all gone, the family dog the only living vestige of his previous life. Carrying the memories of his childhood in his heart, Zeidy set sail for America, hoping to start over and perpetuate his family’s mesorah in a better place.

It’s hard for us to imagine what it must have been like to cross an ocean and know that he was entirely alone in the world. One night Zeidy considered throwing in the towel on Yiddishkeit, but when he went to sleep, he heard a loud voice telling him “lo yamushu mipicha u’mipi zaracha u’mipi zera zaracha.” He woke up with a renewed sense of purpose, and Zeidy would often tell the women in our family that it was our duty to make sure the children continued following the derech hayashar.

While the area surrounding Maimonides Medical Center on Fort Hamilton Parkway may be a frum area today, things were very different when Zeidy settled there after arriving in the United States. Living so close to the hospital, Zeidy felt responsible to help Jewish patients however he could, and he would take my father with him on his Maimonides runs, setting up a percolator with hot water so people could have coffee on Shabbos and bring pans of homemade kosher food.

Throughout the late 1960s and early ’70s, Bubby and some of her neighbors would spend their already-hectic pre-Pesach days cooking Seder food for the Jewish patients, with my uncles making deliveries and saying the basics of the Haggadah with each one before heading home to their own Pesach Sedorim. You have to remember that while today hospitals in many large cities have Jewish liaisons and bikur cholim rooms, things were different back then, and my grandparents stepped in to fill that void, with Bubby helping people get medical appointments and Zeidy spending time cheering up the cholim.

It was on one of those visits that the seeds for Tomchei Shabbos as we know it today were sown. One patient to whom Zeidy spoke told him that he was doing well, but his family was suffering terribly financially because he wasn’t going into work. Having known real hunger during the war years, Zeidy took matters into his own hands, going home and packing up a small box of food that he brought to that patient’s family.

The next week, there were more boxes packed up, and the week after that, there were even more. As word of Zeidy’s efforts got out, his list of recipients grew, as did his crew of volunteers, and Tomchei Shabbos was unofficially launched in Boro Park in 1975. Dozens of boxes were packed up weekly in a small back room in Bubby and Zeidy’s house, and then dropped off under the cover of darkness by volunteers who rang the bell and ran away. Not only did recipients maintain their dignity, since their identities were kept hidden, but the Thursday night drop-offs gave them plenty of time to cook up Shabbos food for their families.

Zeidy came up with the name Tomchei Shabbos came from a pasuk we say every Shabbos morning in Pesukei D’zimra — “nosein lechem l’chol basar.” If you look in certain siddurim, each line of that particular kapitel of Tehillim is accompanied by the name of a malach, and the angel listed by that pasuk is named Tomchiel. It was a concept that resonated with Zeidy — although I doubt when he dreamed up the name Tomchei Shabbos that he ever imagined it would one day become a fixture in Jewish communities around the world.

They say that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and it didn’t take long before other communities approached Zeidy about copying the model in their own daled amos. Of course, Zeidy was thrilled to see more people being helped, and he readily shared both the Tomchei Shabbos logo and any information he could to prevent other Yidden from going hungry.

Tomchei Shabbos outgrew Zeidy’s house as it expanded to cover both Boro Park and Flatbush, and operations eventually moved into a warehouse on 52nd Street and New Utrecht. Our whole family knew that Thursday night was boxes night, which meant that Hershkowitz simchahs had to be scheduled for other times during the week. We all pitched in one way or another — my father would help with the mailings, and one of my cousins and my aunt would do the bookkeeping — and suffice it to say that Bubby was an equal partner in all that Zeidy did.

My grandfather once purchased a new shirt — something he rarely did —after being asked to speak at an event. The shirt was washed, starched, and hung in the closet, but as the day of the event dawned, it was nowhere to be found. Asking Bubby what had happened to the shirt, Zeidy learned that a mother and son had come that day for help, and the mother mentioned that her son was going out on a date that night. Bubby understood that a family that needed help putting food on the table probably didn’t have a proper shirt for the boy to wear on a date, so she gave him Zeidy’s new one.

“You already charmed me,” Bubby told Zeidy. “Let him have the chance to charm someone else.”

That pattern repeated itself so many times in Bubby and Zeidy’s lives. There were more than a few years when they had to borrow grape juice from a neighbor for the Sedorim because they had given all of theirs away on Erev Pesach. People would come to Zeidy on Pesach night asking for brachos, after he told a cousin of mine who needed a shidduch that she would find her bashert that year, and she got engaged on Erev Rosh Hashanah. Zeidy’s smiling assurances to my married brothers that they would come to next year’s Seder with newborns also proved true. Pesach was Zeidy’s night — he would sit in his chair like a king, glowing because he knew he had done whatever he could to make sure people weren’t going hungry.

In addition to being meticulously honest and selfless, Zeidy was also a hard worker. I don’t think he ever took a day off in the 25 years he worked at the Grand Central Station post office. The soul of discretion, Zeidy was once asked by a big Tomchei Shabbos supporter to name just one beneficiary of his legendary Shabbos boxes, just to see where his money was going. Of course, Zeidy refused, but the man kept on pushing, offering to give incredible sums of money to Tomchei Shabbos in exchange for a single name. Still, Zeidy was adamant, telling him the conversation was over, because he would never share that information with anyone.

The supporter looked Zeidy in the eye and said, “I’m so glad to hear that, because my business took a big hit, and I need your help to feed my family. Now I know my secret will be safe with you.”

After Zeidy was niftar at the age of 92 in 2017, there were so many stories that came out. One person recounted that his son used to call Tomchei Shabbos “Tomchei Malach,” because the driver would always ring the bell and leave as soon as the box was put down. This kept up week after week, and the son was sure a malach delivered the food, until the time he opened the door just a little too quickly and saw the driver running away.

Another person told my mother of a family who had just had a baby in the DP camp after the war, and they needed a bed for the newborn. Of course, none could be found, but Zeidy gave up his own bed when he learned of the situation.

“I was that baby,” the woman told my mother. “And I grew up hearing the story of the man who gave up his bed for me.”

Another example of Zeidy’s efforts involved a brother and sister from a respected European family who came to America on a boat full of children destined to be sent to non-Jewish boarding schools. Someone asked Zeidy to speak to the siblings and convince them to stay with families who were shomrei Torah u’mitzvos.

Making that happen was no small feat. Zeidy spent hours begging them, bribing them, whatever it took to gain their trust, and baruch Hashem, he was successful. The boy was sent to Yeshivas Chaim Berlin, while the girl was sent to live with a frum family. None of us knew anything about this at all, until one day my uncle overheard a conversation between Zeidy and the girl, who was by then marrying off her own children into frum families, and had called to thank Zeidy for his efforts.

That was Zeidy. He did what needed to be done, no matter how much work it took, and he did it quietly. He lived to help others and would often tell us that in addition to delivering food to people, Tomchei Shabbos also delivered shalom bayis and menuchas hanefesh. Seeing how Tomchei Shabbos has grown over the years, not only in the packages being delivered weekly to 700 families in Boro Park and Flatbush, but in other communities worldwide, gave him such chiyus in his lifetime, and I have no doubt that he is being richly rewarded for his efforts in the Olam Ha’emes.

Have a Tomchei Shabbos story to share? Please contact Rivka Bar Horin at rivka@thecopysage.com.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 895)

Oops! We could not locate your form.