Finding His Spark

| January 18, 2022Gateshead’s Doddy Gurwicz fuses Torah royalty with cutting-edge science

Photos: Ruskin Photography

It was 1976, and although nearly three years had passed since the Yom Kippur War, the sense of national bruising and shame was still very real for Israelis, who had watched in horror as their tanks were pummelled and decimated by Egypt’s Russian-supplied anti-tank missiles. While the IDF rapidly turned the tide once reinforcements were on the way, disabling Egyptian air defenses and surrounding the Egyptian Third Army in the south, and repulsing Syrian advances in the Golan Heights in the north, Israel paid a heavy price.

Now, at a military base in Haifa in northern Israel, a ceremony of pride and healing was underway. It was the unveiling of a landmark piece of military hardware that was vaunted to become a cornerstone of Israel’s defence capability, representing a momentous step in Israel’s efforts to secure its borders: the launch of the all-new Merkava tank.

Milling around were the best and the brightest of the Israeli defense establishment, including tank warfare expert and Merkava project initiator General Yisrael Tal, mingling with politicians and a smattering of journalists. But what was Mr. Yitzchok Dovid (Doddy) Gurwicz — son of venerated Gateshead Rosh Yeshivah Rav Leib Gurwicz and grandson of famed mashgiach Rav Elya Lopian — doing there?

It turns out that this scion of Torah royalty and talmid chacham in his own right had spent the previous two decades straddling both the halls of Torah and of scientific research and development. He’d traveled to the Israeli event from his native Torah town of Gateshead, because he’d actually played a significant role in the development of this shiny new piece of military hardware that would be a game changer for the IDF.

Forty-five years later, Reb Doddy still lives in Gateshead, and though it’s remained England’s flagship Torah community, the world has changed, and Gateshead along with it. In a town known primarily for its yeshivos, kollelim, and seminaries, there’s also a new demographic. Whereas historically most residents were attracted here for learning or teaching, the last two decades has seen a steady increase in people putting down roots to pursue business and enterprise, settling in alongside the kollel yungeleit and klei kodesh.

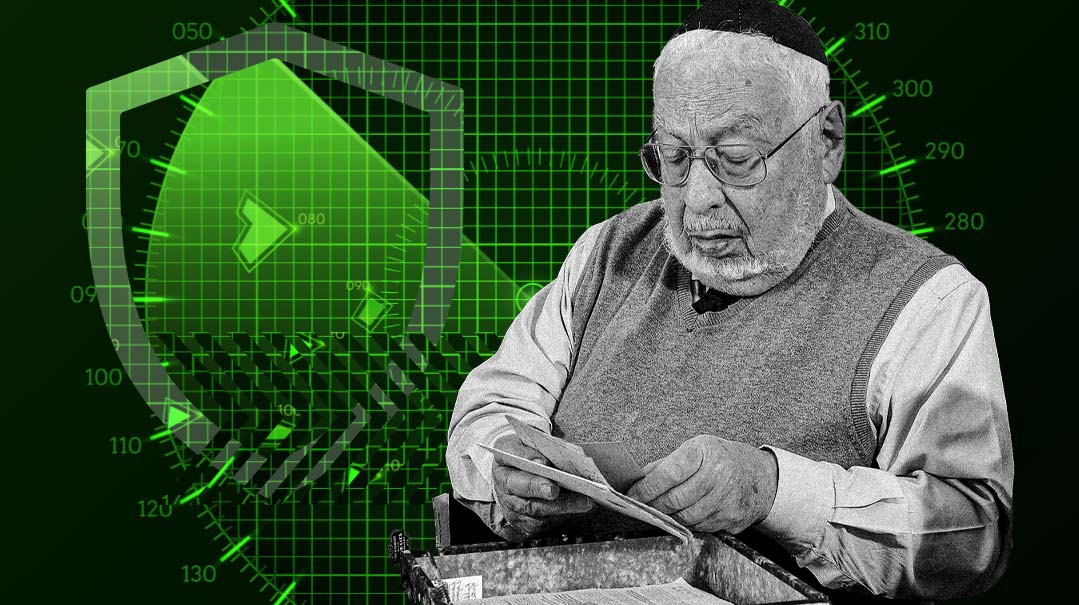

These days Doddy Gurwicz spends his mornings in a kollel, where he’s no longer the only town local to juggle intensive Torah study with a profession; and he devotes much of what’s left of his day to keeping his knowledge of the industry current while also contributing to developing cutting-edge solutions for making sophisticated digital appliances Shabbos-friendly.

Yet even back then, this son and brother of Gateshead roshei yeshivah never saw his engineering profession as more than a job and a way to bring parnassah, always making sure to keep a complete separation between his work and personal life.

Even in Haifa of 1976, when he was feted by the IDF’s top brass and honored by government officials eager to shake his hand, Doddy Gurwicz gravitated instead toward a fellow he spotted who was wearing a yarmulke. “We got to talking,” says Reb Doddy, “and I was astounded to learn that he had been a talmid of my zeide, Rav Elya Lopian, in the yeshivah in Kfar Chasidim! I certainly wasn’t expecting to meet a talmid of my zeide there,” he says.

But that unlikely encounter gave context to the life of a man who achieved international renown in the world of electrical engineering designing sophisticated and complex control systems for big multi-national corporations, while simultaneously occupying pride of place as one of Gateshead’s foremost Torah balabatim.

Understanding how this elder statesman of the Gateshead kehillah — older brother of the current rosh yeshivah who lives just a few doors away, and proud father of children who are all marbitzei Torah — synthesized a trailblazing professional career while staying true to his values and prestigious forebears, is a lesson in perspectives and priorities.

Staying Safe

The East End of London of the 1920s and ‘30s was a pulsating center of Jewish life, yet although Yiddish was the predominant language, religious observance was in steep decline. Shabbos observance was poor, and Yiddish theater drew more people than Shabbos morning services.

One shining light in that cultural melting pot was the tzaddik Rav Eliyahu (Reb Elya) Lopian. A man whose Kelmer-style mussar shmuessen influenced many thousands of talmidim and whose classic Lev Eliyahu is a fixture in many a Torah library, he had relocated with his large family to London in 1928, assuming leadership of the Etz Chaim Yeshiva in the East End.

In 1931, when his eldest daughter, Liba, reached marriageable age, Reb Elya made the trip back to der heim to seek out the kind of quality shidduch found only in the finest of Lithuanian yeshivos. Head to Mir yeshivah, he was told, and look for one of the “lions,” a bochur by the name of Leibele Malater (from Malat, Lithuania). Although he had been born Aryeh Ze’ev Kushelevsky, as a bochur Reb Leib had reason to travel between Lithuania and Poland. However, obtaining a visa to travel from Lithuania to Poland was no simple task due to a political deadlock, and the only solution was to obtain a Polish passport. Reb Leib was directed to a bochur who was an expert forger (as payment for the forgery, Reb Leib offered to tutor the talented counterfeiter in some high level Ketzos, the currency he knew best), and along with the new passport came a new name as well — his mother’s maiden name, Gurwicz.

A graduate of Brisk and other top level pre-war yeshivos, young Leib (Aryeh Ze’ev) was known for his sterling middos and unwavering hasmadah, and the shidduch was finalized. Leib and Liba were married in London in 1932 and their bechor, Yitzchok Dovid, was born a year later.

Reb Leib took up a post as rav of the Great Garden Street Federation Synagogue in the East End and also gave a shiur at his father-in-law’s yeshivah.

During the war years, they were evacuated together to Letchworth, a village in the English countryside. “In Letchworth, we started out in a three-bedroom house,” Doddy remembers. “In one bedroom lived Rav Nosson Ordman, an outstanding Telzer talmid chacham, with his family. In another room lived my parents and my younger siblings, and the Zeide Reb Elya and I shared the third room. I was only six or seven years old at the time, but my zeide’s nightly Krias Shema left a lifelong impression on me. I also had the zechus to wrap his legs every night in bandages to help relieve the discomfort he suffered as a result of poor veins.”

Letchworth was host to a number of other Torah personalities during the war years, including Dayan Yechezkel Abramsky and Rav Yosef Yona Tzvi Halevi Horowitz, the Frankfurter Rav, who assumed rabbinic leadership of the small, temporary settlement.

The Blitz raged in London and other cities of strategic importance across the United Kingdom, leaving a trail of death and destruction. Night after night, German bombers ventured across the English Channel on a mission to unleash deadly payloads, flattening buildings and snuffing out innocent civilian lives.

Letchworth, in the quiet countryside, was far removed from the chaos and destruction. Reb Doddy was just a child, but one of the most frightening moments in his life still remains fresh in his memory. As he and some other boys were walking home from the local school for lunch, a distant rumble in the air caught their attention, slowly morphing into a loud whine. The sound of an aircraft engine wasn’t unusual during wartime, and the boys turned to wave at the plane as it appeared over the trees. But as the plane drew closer, flying at an unusually low altitude, the boys suddenly spotted the unmistakable markings of the German Luftwaffe — the cross and dreaded swastika. This was no friendly aircraft. It was a German bomber in a speedy, determined descent toward its target — a group of indefensible Jewish school boys.

Seeing the pilot gesture to the gunner, the boys realized they were that day’s target practice for the German crew. As the killing machine’s guns activated, spewing lethal lead into the ground all around, the boys managed to dive into a nearby ditch, escaping with their lives.

“I could see the Luftwaffe pilot’s face,” relates Reb Doddy, “that’s how close he was. I saw the bullets rake the road surface just ahead of us.”

Staying safe from the dangers of war while maintaining his communal and rabbinic commitments was a challenge for Reb Leib, who didn’t desert his two London positions, even during the Blitz.

“Every morning at 7 a.m., my father and Reb Elya would travel on what was known as the ‘workmen’s train’ back to London. The Yidden had their own train compartment, and they would daven Shacharis on the train.”

German planes would sometimes take aim at the moving trains, and the commuters, seeking safety, would try get into the “rabbi’s carriage” for the journey, sensing that the spiritual environment would provide some kind of refuge. Reb Elya and Reb Leib’s train was never bombed.

Pointing North

“My father and Reb Elya bought a house together in Stamford Hill, an area of North London populated by frum Yidden and eventually, many war survivors,” says Reb Doddy. But while Reb Elya moved to that area, Reb Leib stayed behind to shepherd his East End congregation, even as the neighborhood was in great spiritual decline.

It was an encounter at a very young age that shaped Reb Doddy’s outlook and eventually helped him navigate the two opposite worlds of his future life.

One Shabbos morning on the East End found six-year-old Doddy passing an auto garage. Doddy, technically curious even at that young age, stopped to watch a mechanic as he leaned over the hood engrossed in his work.

“I was always interested in how things worked, taking things apart and testing them out,” says Reb Doddy. “But the mechanic was a Jew, and when my father found out, he was deeply disturbed that I should witness blatant chillul Shabbos.”

From then on, Doddy stayed in Stamford Hill with his uncles, aunts, and illustrious grandfather. Living in such close proximity to his zeide, a towering Torah and mussar personality, left an indelible mark on his young grandson.

Young Doddy learned his lesson; although he would later pursue a highly successful career in electrical engineering working with senior scientists across the globe, it was never at the expense of his values.

After the war, life returned to normal. The extended family returned to live in Stamford Hill, and Doddy enrolled in the Avigdor School set up by Rabbi Dr. Solomon Schonfeld, while his younger brother Avrohom — today the esteemed Gateshead rosh yeshivah — was sent to join the Gateshead Jewish Boarding School.

Reb Leib too was seeking a challenge, looking to spread his wings further. His shul in the East End was in decline, many of his congregants having moved away to areas of North West London such as Golders Green and Hendon. Reb Leib himself walked from Stamford Hill every Shabbos morning to be with what remained of the kehillah. And the relatively low-level shiur he delivered at Etz Chaim wasn’t providing the intellectual stimulation he was capable of. At the time, the opportunity of a career move to Sunderland presented itself, and as the current rabbi was retiring, Reb Leib put himself forward as a candidate. (Sunderland, 20 minutes south of Gateshead, was a bustling metropolis of Jewish life in those years.)

The barometer of success for any aspiring rabbi in an English synagogue was the ability to deliver a flawless sermon in polished English, a task that Reb Leib, an immigrant, would undoubtedly struggle with — but it was a non-negotiable part of the application process. He asked a relative to write out the derashah for him in English and made the trip to Sunderland.

The sermon was about Yetzias Mitzrayim, and the board and the congregation listened as the foreign rabbi with the heavily accented English repeatedly pronounced the word Egypt as “egg-wipt.” It wasn’t exactly the type of congregational rabbi they were looking for.

But Sunderland’s loss would be Gateshead’s eternal gain. Reb Leib’s brother-in-law, Rav Leib Lopian, was learning in the famed Gateshead Kollel and delivering a shiur in Gateshead Yeshivah. The yeshivah was experiencing a period of exponential growth fuelled by the post-war influx of orphaned refugees saved from the Nazi inferno, and they were in need of another maggid shiur. Rav Leib Lopian recommended his brother-in-law Rav Leib Gurwicz, and thus, in winter of 1947, the Gurwicz family settled in Gateshead.

Their arrival heralded a watershed moment for the small coal-mining town in the heavily industrial northeast of England. The name Gurwicz would cement Gateshead’s status as Europe’s foremost Torah town, as Reb Leib, who would soon become rosh yeshivah, fuelled the steady growth of the yeshivah to become the bastion of Torah excellence for which it is still renowned.

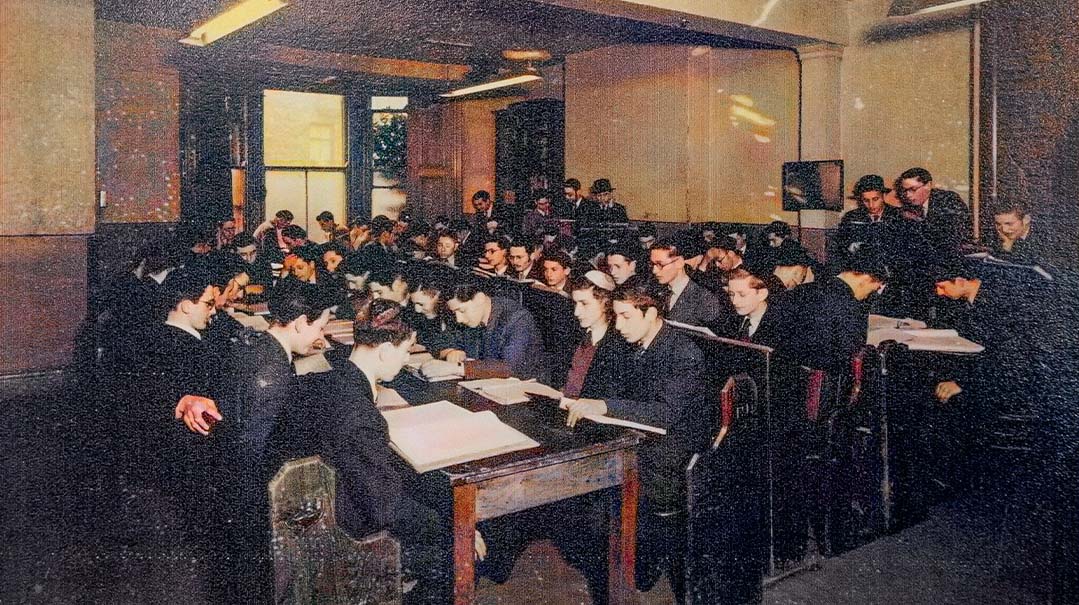

Doddy Gurwicz joined the 90-strong yeshivah a year later, after completing his high school matriculation. He recalls the many refugee bochurim, complete orphans, alone in the world, supported like their own children by the mashgiach Rav Moshe Schwab and the menahel Rav Eliezer Kahan. The rosh yeshivah at the time was Rav Moshe Landynski, who was sent by the Chofetz Chaim back in the 1920s to lead the nascent yeshivah.

Although at the time, in this small settlement of around 30 families, not all ladies covered their hair, and the sit-down kiddush after Shabbos morning davening didn’t have a mechitzah, the town’s founding principle of staunch adherence to Shabbos observance united the band of hardworking families, laying the groundwork for the flourishing Torah community it is today.

Closing the Circuit

Having learned in yeshivah for a good number of years, Doddy was at a crossroads. His penchant for science and engineering was pulling him, and an evening class in electrical engineering at Gateshead Technical College seemed like a good starting point for his inquiring mind. But as a yeshivah bochur hailing from a dynasty of Torah greatness, this was not going to be an easy choice.

Reb Leib, sensing his son’s appetite to expand his knowledge, made a condition that showcased the Rosh Yeshivah’s foresight and vision in guiding his son: study for semichah during first and second seder in yeshivah, and attend classes in the evening.

“My father wanted to make sure I would stay rooted in the safe confines of the yeshivah while trying my hand at formal study in an area that genuinely interested me,” Reb Doddy relates.

With this directive in hand, Doddy stuck to his part of the deal. In 1954, he received his semichah from Rav Rabinow of London; yet unbeknown to him at the time, his father’s insistence that he take semichah would push his trajectory toward a career in his chosen field.

A while later, he applied to Newcastle University, across the river from Gateshead, for their electrical engineering degree course. And ironically, it was his semichah that swung it for him. Usually students were only accepted straight from secondary school, and with Doddy arriving at a later age, they weren’t inclined to accept him. But the semichah gave him credentials as an advanced student and ensured him passage into the professional world.

Seeking means of support to fund his studies, he decided to interview for a position teaching in the Newcastle cheder. Rabbi Toperoff, the community rav, sat the young man down for a conversation over some good English tea. A young and eligible Miss Toperoff served her father and the guest — and thus Doddy met his wife.

With his funding secure and a supportive wife by his side, he emerged after four years in university with an honors degree in electrical engineering.

Current Events

Doddy entered the world of electrical engineering at a watershed moment in the industry.

The old thermionic devices that converted thermal energy to electricity had been around since 1904, a staple component of electrical devices. But now, tiny and reliable transistors were changing the face of electronics, replacing the old thermionic valves. The new transistors led eventually to the creation of integrated circuits that contained millions of small electrical components and was the foundation of modern electronics, paving the way for the dominance of digital computers and much of our modern communication.

Doddy was hired by a German Jew named Loebl who ran a business in the Team Valley Trading Estate in Gateshead. He was tasked with carrying out research and development work, becoming involved with equipping the materials handling systems of high amperage devices with electronic controls.

He quickly saw success in his work. The firm landed a contract to develop the electronic control systems for the forklift truck — a technology still in use today. So ground-breaking and pioneering was his work that it earned him the coveted title of Fellow of Institute of Technical Engineers (FIET), as well as the Queen’s Award to Industry in 1970, resulting in an invitation to Buckingham Palace for a meeting with Her Majesty the Queen in person.

Eventually Mr. Loebl’s company merged and formed Sevcon, which developed electronic systems for electronic vehicles. Reb Doddy became managing director, and over the next decade built the company into a lucrative concern. Yet despite his huge investment of time and talent, he refused to take a stake in the company, as it was owned by a Jew and operated on Shabbos.

“We ended up building the control systems for the first electric car that Ford conceptualized — which landed in the London Science Museum,” Reb Doddy relates. He also worked on the first electric bus and helped develop a scanning machine used to closely examine pictures of the moon surface in order to determine the optimum sites for moon landings.

At the same time, Doddy and his wife were raising their family in Gateshead, living next door the Gateshead Rav, Rav Betzalel Rakow, and a few doors down from his brother Rav Avrohom, who was then a maggid shiur at the yeshivah. Reb Leib Lopian and his brother Reb Chaim Shmuel also lived close by.

“Although my father wasn’t part of the yeshivah, the yeshivah was very much part of our family and influenced our childhood in a strong way,” his daughter Mrs. Gila Wolf remembers. “After Reb Leib Lopian’s wife passed away, he joined our family every day for meals, and with that came conversations around all the goings-on in yeshivah. Add to the mix our Lopian cousins and uncles, and we were surrounded by Torah — learning and teaching.”

The combination of living among Torah greats of world-class caliber, and a father who maintained an uncompromising connection to that world, left an indelible impression on the children.

“I remember going to pick up my grandfather from the station and arriving back at yeshivah where throngs of bochurim surrounded the car and sang the Rosh Yeshivah into his home. I felt so proud to carry the last name Gurwicz,” Mrs. Wolf says.

Although Reb Doddy had no clients in the northeast of England and was forced to travel away from home extensively for business, the Gurwiczes kept the family in Gateshead for their children’s chinuch. With that upbringing, it’s no wonder that all of the six Gurwicz children charted a path in the world of Torah and chinuch — all of Reb Doddy’s sons and sons-in-law are involved in Torah education in schools, yeshivos, and seminaries in Gateshead, Manchester, London, and the USA.

“Learning has always been paramount for my father,” says Mrs Wolf, “and he is immensely proud of his children and the contribution they’ve made and continue to make to the Torah world.”

Reb Doddy quickly gained renown in the town as the epitome of a “Torahdige balabos.” “He was a bit of an anomaly in Gateshead back then,” Mrs Wolf reflects. “Although there were a number of balabatim involved a range of different industries, my father pursuing a degree and then flying all over the world for his job was something quite of the box for little Gateshead.”

Reb Doddy, however, had his non-negotiable time set aside every night for learning. “I learned for 35 years with the parnes (president) Mr. Yosef Kaufman,” he recalls, “and after he passed away, Rav Rakow himself became my chavrusa.”

Doddy also learned every Shabbos with his father, Reb Leib; and to her eternal credit, Doddy’s wife a”h stood steadfast in ensuring that his learning time remained sacrosanct and undisturbed.

The company was sold in 1974, and two years later, Reb Doddy decided to strike out on his own, creating Nada Electronics.

The high point in his career came when his expertise caught the attention of the IDF, beginning with a call from Elbit Systems, a company subcontracted by the IDF that was tasked with building the control systems for the new Merkava tank. This advanced piece of military hardware was touted to become the backbone of the Israeli army’s armored corps, and the government was pouring huge resources into the project.

However, the development team had hit a wall — in an area that was precisely Doddy Gurwicz’s line of expertise. “Our company was specializing in developing control systems for high current pieces of equipment, such as MRI machines and high-powered magnets that work on a thousand amps or more — that’s around a hundred times more powerful than a common household appliance,” Reb Doddy explains. “Now, the turret of a tank is very heavy and requires extremely high power to oscillate and elevate. At that time, the standard American and British tanks used hydraulic systems to power the movement of the tank’s systems. But for the Israelis, operating in desert conditions, the sand would be damaging for the hydraulic systems and was far from ideal. They wanted an alternative method to power the Merkava’s turret, and the Israelis hit on a completely novel, untried idea: to power the turret using electronic systems, precisely my specialist area of expertise.”

An Israeli who had worked for Reb Doddy in the past in Gateshead and was now with Elbit made the introduction. Doddy landed the prestigious Israeli defense contract and got to work, traveling to Israel regularly to work on the mammoth project.

Follow the Light

Around 20 years ago, after many successful years in the industry and with dozens of long-range achievements to his credit, Doddy Gurwicz sold his company. Far from signaling a slowing down, though, it enabled him to devote more of his day to pursuing the love that has been central to his life — learning Torah.

For many years he was the natural choice as substitute to deliver the town’s longest-standing daily Gemara shiur in Gateshead Shul when the regular maggid shiur was not available.

In addition, the octogenarian now devotes his morning to learning with a chavrusa in the new kehillah kollel surrounded by people young enough to be his grandsons.

A recent addition to Gateshead’s impressive roster of thriving mosdos, the new kollel, launched by Zelig Kupetz and friends, was initiated in order to encourage more yungeleit to move to the town, as well as to provide an open beis medrash for anyone wishing to spend time learning. Doddy has made it his place.

“Gemara is his natural home,” says Dovid Katz, one of his daily chavrusas and Gateshead’s Hatzolah coordinator. After Rav Rakow passed away, Doddy, seeking a new chavrusa, asked Dovid if they could learn together, even though the latter is many decades his junior. “It’s a privilege and an honor to learn with him. I call our daily time together my ‘golden hour.’ ”

Simply being with Reb Doddy is a lesson in middos, humility, and magnanimity. “Some very smart people find it challenging to learn with people not on their level,” Dovid continues, “but Doddy has the patience and humility to explain things on a normal level. He makes space for me in the chavrusashaft, he takes my questions seriously. And this is someone who remembers everything he ever learned, so it’s a bit like learning with an ArtScroll Gemara.”

In a town that is seeing change, he is also treasured for his connection to the Gateshead of yesteryear and its timeless values. “For me, he is a precious link to the values of Rav Rakow and his predecessor Rav Shakovitzky,” says Dovid. “And he’s a sterling example of kevod rabbanim and kevod haTorah, always prioritizing those values when considering an issue. He’s also a living lesson in consistency, learning with the vigor of a yeshivah bochur — and usually with people half his age.”

For Doddy, it’s a home away from home, and his example shows a way forward in an increasingly confusing world, as he wears with ease a status that is becoming more prevalent in Europe’s premier Torah town. In an era where maintaining a work-life balance is an increasing challenge, Doddy continues to deliver on the promise he made to his father: learning Torah always comes first.

Since retirement, Doddy has found a new application and avenue of expression for his substantial technical knowhow. As household appliances become increasingly automated and sophisticated, numerous halachic challenges relating to Shabbos observance are thrown up. For example, a government initiative to install “smart meters” measuring domestic electricity, gas, and water consumption in real-time could result in chillul Shabbos every time a tap is switched on. Reb Doddy has become the go-to address for rabbanim and dayanim looking to understand the issues involved, applying his lifelong experience and knowledge to real-life halachic issues affecting Torah households. And, he refuses to charge for his services.

This coming together of halachah and science is yet another manifestation of a lifetime spent straddling two very different worlds with aplomb, unflinchingly staying true to his values and prestigious lineage throughout. Divinely engineered, you could say. —

THE BEST-LAID PLANS

The original plan for Liba Lopian and Leib Gurwicz was that the young couple would leave London for Lithuania after their wedding, where Leib would continue learning. But one day during their engagement, a letter arrived for the chassan that would change everything. Liba wrote from London to share the tragic news of the untimely passing of her mother, leaving her — the eldest of 13 — with the responsibility of caring for her siblings in London. With this change in her circumstances, she could not possibly commit to living in Lita after their wedding, and she would understand if Leib would wish to break the engagement.

Saddened for his kallah’s plight yet unsure of how to proceed, young Leib resolved to travel to Radin, to seek counsel from the Chofetz Chaim. Making the trip from Mir to Radin, he entered the Chofetz Chaim’s room and beheld the tzaddik wrapped in tallis and tefillin. He explained his dilemma: either travel to England for good, or break the shidduch.

The Chofetz Chaim opened his holy mouth to speak, uttering just a few words from the tefillah Baruch She’amar: “Baruch podeh umatzil, baruch Shemo.” Thinking that the Chofetz Chaim had misunderstood, the young questioner repeated his query. But the Chofetz Chaim responded with the same words: Hashem is the ultimate redeemer and savior. And with that, the audience was over.

Initially puzzled by the gadol’s terse and cryptic response, after some reflection, the message became clear: Follow through with the shidduch, and all will be good. Hashem is on your side.

Before long, as Nazism gained traction, and the winds of war began blowing across the continent, people started to seek avenues of escape. Now the prophetic words of the Chofetz Chaim proved prescient: Because he was safely in England, Reb Leib was in an advantageous position, able to arrange safe passage for his wife’s siblings, the Lopians, then learning in the yeshivos of Mir and Telshe. Reb Leib now understood: Baruch podeh umatzil.

Sadly, Reb Leib’s own father, Rav Moshe Aharon Kushelevsky, a dayan in Malat whose singular trip to the UK was for the occasion of his son’s wedding, perished with his family in the Nazi inferno. He had been offered the rabbanus of Gateshead while in England for the wedding, yet declined, preferring to return to the more spiritually secure environment of his hometown.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 895)

Oops! We could not locate your form.