Cracking the Code

| December 7, 2021A geneticist and rabbi find our Jewish mothers embedded in our DNA

I

n these days of sophisticated DNA research, is it possible to establish Jewish lineage with a simple cheek swab? Leading geneticists have discovered that the special genetic sequences transmitted exclusively from mother to child might be a key to tracing Jewish identity inherited through the maternal line. And Rabbi Zev Litke, a dayan specializing in family research, is already using the evidence to enhance claims of Jewishness in rabbinical courts

When a well-known Swiss entertainer decided to take one of the many newly-popular and affordable DNA tests, he was so enthusiastic about discovering his family history that he opted to announce the results live on his television show. While his parents emigrated from Turkey 50 years ago and he identifies with his Turkish-Muslim ancestry, he was in for a shock: When he opened the envelope in front of a live audience, the results showed that although he’s 15/16 Turkish-Muslim, he’s also 1/16 Jewish. And not just Jewish, but Ashkenazi Jewish. That means the Jewish strain in his family went back just four generations.

His identity might have been seriously upended, but today, the ability to authenticate Jewish ancestry has taken on a new urgency, especially among the Eastern-European immigrant community in the Holy Land. In Israel, the Law of Return grants near-automatic citizenship to immigrants with at least one Jewish grandparent, but the chief rabbinate only recognizes them as Jews if they have a Jewish mother. These two differing qualifications leave many immigrants in limbo: According to the State, they are considered Jewish and are listed as such on government forms. But according to the Rabbinate, they cannot marry in Israel or be buried in a Jewish cemetery unless their halachic Jewishness is confirmed.

For the many immigrants who did not arrive from established Jewish communities that could attest to their members’ Jewishness, obtaining authentication is often impossible. Additionally, often the documents presented are either smudged originals, blurry photocopies, or forgeries. The result is often frustration, pain, dashed hopes, and no little resentment.

But in these days of sophisticated DNA research, is there an easier way of corroborating family ties than sifting through dusty prewar archives? What if a Jewish connection, and more specifically, a maternal one, could be verified with a simple cheek swab?

Backward Link

Five years ago, a select group of scientists on the cutting edge of genetic population studies met with senior dayanim in Jerusalem to discuss this very question. The rabbanim were looking for a solution to help the thousands who couldn’t prove their Jewish origins but still claimed Jewish maternal ancestors. The dayanim included Rav Zalman Nechemia Goldberg ztz”l; Jerusalem posek, rosh yeshivah, and author of the Minchas Asher series Rav Asher Weiss; Rav Yehoram Ulman, head of the Sydney beis din; Rav Yisrael Barenbaum, head of the Moscow beis din; and Rav Zev Litke, a talmid of Rav Weiss who had been part of Rav Yosef Fleischman’s beis din in Jerusalem. The scientific team was led by Professor Karl Skorecki, a Canadian-born nephrologist and genetic researcher at Rambam Medical Center, who in 1997 identified the “Kohein” gene, the genetic markers shared by Kohanim who trace their ancestry to Aharon HaKohein.

The focus of Professor Skorecki’s newest study was mitochondrial DNA, which unlike nuclear DNA, is transmitted exclusively from mother to child — perfect for tracing Jewish identity as it is inherited through the maternal line. He discovered that within certain populations, there are typical genetic markers in the DNA of the mitochondria specifically — and particularly among Jewish communities — and these markers link back to a small subgroup of women who came to the European continent from the Middle East. Over the years, this population has accumulated genetic markers that distinguish it from other populations of the world.

Working with Eastern European population databases, the researchers found that certain mitochondrial DNA sequences could be found in a meaningful percentage of the Ashkenazi Jewry sample, while they are nearly absent among non-Jewish European populations. That means that in many cases, it’s possible to identify whether the mother or maternal grandmother of the person in question descends from a Jewish gene pool.

The following year, Rabbi Yisrael Barenbaum of the Moscow beis din together with Rabbi Zev Litke released the book Determining Jewishness in Light of Genetic Research (Hebrew), making the halachic argument that tests of mitochondrial DNA, or mtDNA, could sometimes be used as supplementary evidence to enhance a petitioner’s claim of Jewishness in a rabbinical court.

Rabbi Litke is careful to stress, however, that test results — already recognized as legitimate evidence by many dayanim — are never a proof of Judaism, but only a method of corroboration in cases where other documentation, or some kind of reliable family narrative, exists — and only as a last resort if other information falls short. Moreover, he stresses, a “negative” test can never be used to call someone’s Jewishness into question, because more than 60 percent of Ashkenazi Jews don’t have the marker.

The mtDNA test results are examined on a case-by-case basis and can frequently prove inconclusive. What Rabbi Litke looks for is a statistical majority of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry in comparison with general population databases.

“I even tested myself early on to see what would come up, and actually I was a bit surprised — my DNA sequence didn’t match any of the Jewish markers known at the time,” Rabbi Litke reveals. “Since then, our data has expanded, and today I’ve identified my sequence as belonging to an Ashkenazi group. Actually, my sequence is found in five out of 600 Jews and isn’t found at all in a pool of hundreds of thousands of non-Jews. So while this alone isn’t a ‘proof’ of my Jewishness, it’s very strong evidence that could be used to uphold a decision in a beis din.”

Rabbi Litke, though, never had reason to question his Jewish connection. He spent his yeshivah years in Grodno in Ashdod and went on to learn in Rav Asher Weiss’s kollel. Over the years, Rabbi Litke became an expert on the halachos of pesulei chitun (those with halachic restrictions on marriage, due to such questions as, for example, whether the mother received a get from her first marriage) and lineage issues — starting out when a family member with a personal dilemma enlisted his help during the time he was a dayan on Rav Fleishman’s beis din.

Several years ago, Rabbi Litke met Rabbi Barenbaum, who had already begun applying test results in his own rabbinical court. He dealt with dozens of cases where genetic research helped resolve doubts about a petitioner’s Jewishness, either by using mitochondrial tests to link subjects to the “mothers” marker, or via tests pointing to a DNA link to known Jewish relatives on their mother’s side. His rulings, however, were only recognized in the local community in Russia.

He and Rabbi Litke then began lobbying rabbinical judges in Israel and Europe. The effort, Rabbi Litke concedes, has been expectedly slow-moving. Those dayanim who support the effort are primarily motivated by their compassion for the immigrants who are abruptly thrown off by the questioning of their Jewish status.

“A person goes to the Rabbanut before his wedding, but the dayan tells him, ‘Look, the evidence you have of being Jewish is really meager, and I can’t change that, so I won’t be able to allow you to marry a Jew.’ But the dayan is sensitive and wants to help,” says Rabbi Litke, “so today he can tell the petitioner, ‘Maybe try the DNA option and see what comes up?’”

Uncontested Evidence

It sounds so simple on paper. If we can analyze our genes to find out if we’re susceptible to obesity or anger issues, why can’t we use it to discover something about our Jewishness?

DNA is arranged in different sequences, which are codes for our genetic makeup. That’s not news to science, and even the existence of mitochondrial DNA has been known for decades. But it wasn’t especially useful to non-Jewish researchers. Who benefits from knowing about their mitochondrial genes? Well, Jews do.

“We’re talking about a relatively small group that has married primarily within its own community,” says Rabbi Litke. “You take DNA samples from a group of several hundred Jews whose Judaism is established beyond doubt. You then feed the sequences into the databases of DNA samples from non-Jewish populations from similar regions. These databases often contain hundreds of thousands or even millions of samples.

“We’re highly likely to discover certain DNA sequences among the Jews and not among the gentiles. Let’s say that out of 1,000 Jewish samples, we discover a given marker 20 times. We then go back to the much larger database of half a million non-Jews, where we’ll find only a handful of instances of it. In other words, it’s significantly more common among the Jews sampled, and since the Jewishness of the smaller Jewish group is beyond doubt, we can tentatively establish that anyone carrying that marker is likely to be Jewish.”

The corollary, notes Rabbi Litke, is that if non-Jews are carrying the sequence, it’s likely that there is Jewish blood in their populations as well, and those carriers might unknowingly be Jewish themselves.

It’s not only people who want to marry according to halachah for whom this verification is important. Many who consider themselves Jews but are unsure of their lineage can today contact Rabbi Liktke’s organization, Simanim, which assists people in their search to determine their maternal origin through genetic testing. At the present time the test is relevant to Jews of Eastern European Ashkenazi descent, and has an especially high rate of success among Caucasus and Georgian Jews because of comparable available data bases.

Rabbi Litke has been there for dozens of people who’ve finally been able to resolve their questionable yichus. One case he recalls is that of Svetlana, born in Ukraine in 1941, in the middle of World War II.

“She was raised by a Ukrainian family, and married, had a daughter, and then grandchildren in Ukraine,” Rabbi Litke relates. “But the couple who raised her weren’t her birth parents. As a baby she had been found near the railway tracks with a note stating the date of her birth. It’s highly likely that she had been left there by a Jewish family in an attempt to save her while they perished.”

Svetlana, who always suspected she was Jewish, approached Rabbi Barenbaum in Moscow. He referred her to a mitochondrial DNA test, which showed clear indications of Jewish mitochondrial heritage. Further genetic testing indicated that she had relatives in Israel, and through them, she learned that family who was likely hers was murdered in the Holocaust.

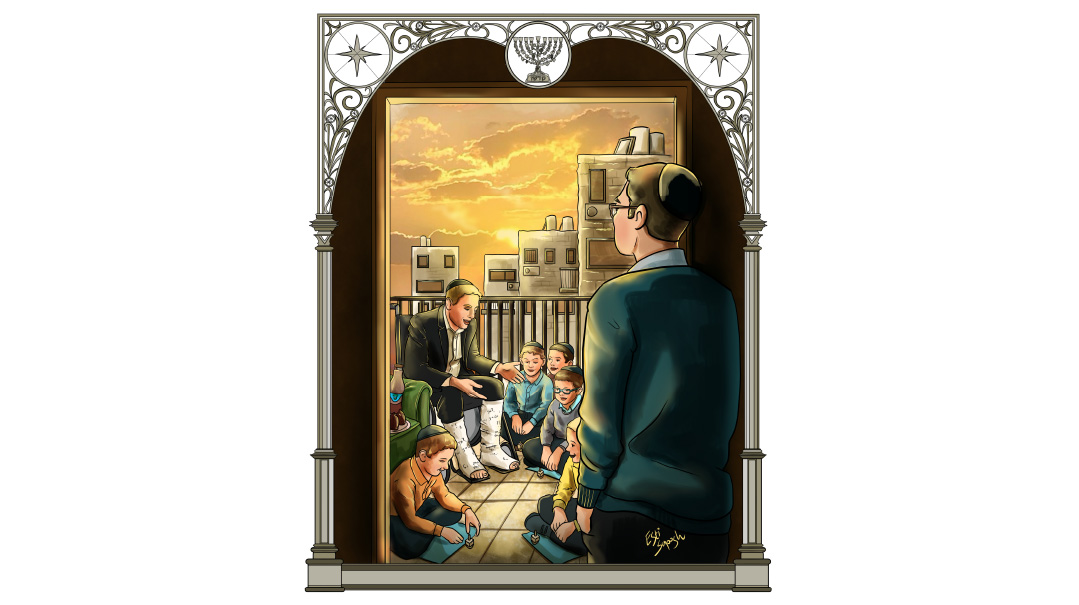

In another case, a large family arrived in Israel from Zhitomir in Ukraine — a grandmother, her five daughters, and her grandchildren. The men in the family were non-Jews, but due to the mothers’ Jewish identity, the children and grandchildren were Jews.

The entire clan made aliyah 20 years ago under the Law of Return and tried to secure the state’s certification of their Jewishness. The woman had no documents, but she had a story that was known in the family: Her mother had married a non-Jew who died years back, her daughters also married gentiles, but she herself was a Jew.

For years the family members couldn’t get their Jewishness recognized by the Rabbinate and its affiliates, and one of the grandsons was refused admittance to a religious school. But about three years ago, the woman was referred to Rabbi Litke and his partner in Simanim, Rabbi Pinchas Gotthold. “The results were unequivocal: The family has very distinct Jewish markers, so the positive result was very high,” says Rabbi Gotthold, “and ultimately every one of the 15 members of the family secured official recognition as Jews.”

Sometimes, discoveries by this groundbreaking technology can save families from falling apart. Like in the case of the Jewish man from New York who left religion and decided to marry a woman of Danish descent. “She told his family that she had heard she had Jewish roots,” says Rabbi Litke, “but there was no hard evidence. She claimed that her grandmother’s grandmother had emigrated from Odessa to Poland, where she had married a non-Jew.”

The family members of the man, who were ready to cut off ties with their son, turned to their rabbanim to ask them what to do. The case reached the desk of Rabbi Yehoram Ulman, who’s been head of the Sydney, Australia, beis din since 1994, and who has dealt extensively with Jewish lineage questions. He suggested that this woman do a mitochondrial DNA test, and while the results in themselves are not proof of Jewishness, it turned out that her mitochondrial sequence clearly indicated her connection to Eastern European Ashkenazi Jewry.

Rabbi Ulman, who is an active proponent of DNA test results as corroborative evidence in determining Jewish status, is clear about his mission statement: that whenever new avenues and new angles come up in science that can assist — not change — halachah, they shouldn’t be pushed away but explored to see how they can be used to help people. In fact, Rabbi Ulman continued researching this woman’s background on his own and turned up additional evidence of the extended family’s Jewish origin. Today some of those on the matrilineal line have even become mitzvah-observant.

You Can’t Fake DNA

Early on, Rabbi Litke and Rabbi Barenbaum presented their findings at the Conference of European Rabbis and to the dayanim at the Rabbanut in Eretz Yisrael.

“All rabbanim of European kehillos and every dayan dealing with proof of Judaism in Israel face endless requests for verification of Judaism and conversion,” Rabbi Litke says. “Suddenly, by taking a simple test and then comparing the data, we can establish a very high probability of Jewishness. And while the documents the courts rely on can be faked, DNA can’t be faked.”

Rabbi Likte tells of a bochur with Russian parents — a Jewish mother and a gentile father — who became frum and was learning in an Israeli yeshivah. But when he went to register for marriage, he was told that his parents’ documents were forgeries.

“Of course, the bochur himself knew nothing,” says Rabbi Litke. “The family finally admitted that the grandmother’s grandmother was a Jewess who married a non-Jew in 1914, and while the mother-daughter line remained Jewish, most of the subsequent generations married out as well. But how to prove the existence of a Jewish great-great-grandmother from a century ago?

“In his distress the bochur turned to us, and we were actually taken by surprise — their version of the story was indeed corroborated by the findings. His genetic sequences matched a well-known Ashkenazi haplogroup — a genetic population group of people who share a common ancestor — and there are no known non-Jews with that identical sequence.”

Currently Rabbanut-affiliated batei din in Israel recognize these tests as part of a bigger picture of piecing together proof of Jewishness. Most often they are used as a supplement to documentation deemed otherwise insufficient to establish Judaism, and sometimes they are supplemented by further tests. “So it’s not exactly accurate to say ‘the Rabbanut accepts genetic testing,’ ” Rabbi Gotthold qualifies. “No beis din uses these results alone without some other kind of evidence.” But they are certainly becoming a respected piece of the puzzle.

Rabbi Litke shares the case of a man who was born in a remote Ukrainian village. Upon hearing from the village elders that he was descended matrilineally from a Jewish mother, he went to a rabbi in Kiev and told him he was ready to reclaim his Jewish identity. The rabbi told him that it isn’t possible to find documents from the 19th century and recommended that he undergo a conversion l’chumra — just in case. The convert became attached to Chabad, married, and made aliyah.

“The man had four sisters who din’t have right of aliyah under the Law of Return, because they didn’t convert and couldn’t produce any documentation of Jewish lineage. He turned to the beis din, the beis din referred him to us, and the testing indicated that he was an Ashkenazi Jew beyond reasonable doubt,” says Rabbi Litke. “We sent them a report, and in the end, researchers located the document testifying to his great-grandmother’s conversion to Christianity. Her given name was Rochel Baila. Ultimately all the sisters were certified as Jews and made aliyah.”

Of course, it isn’t only Eastern Europeans who claim Jewish ancestry. While people are extremely curious about the descendants of the Anusim, for example, Rabbi Gotthold explains that at this point there is not enough conclusive data about their gene pool. “Spain isn’t part of our calculations,” he explains, “because we haven’t yet isolated Jewish markers that could help us identify the Jews among them. But we estimate that the percentages of invisible Jews there is even higher than the rest of Europe.

“Remember, the expulsion of the Jews from Spain created an entire generation of Anusim, which means that there is Jewish mitochondrial DNA passed down from mother to daughter for 500 years, encompassing hundreds of thousands of people. When we’ve collected enough information about modern DNA types among Sephardi Jews, we’ll be able to search for them in the databases of non-Jewish Spaniards, and who knows? Maybe we’ll detect a great many unknown Jews among them.”

Sometimes the test is a trigger for something bigger. “One day,” Rabbi Gotthold recounts, “I was approached by a well-known Swiss lawyer who held a position at the EU HQ in Brussels, and he claimed that he was of Jewish descent. His DNA test was relatively promising, but I didn’t feel able to verify his claims based on that alone. Still, the results were enough for him to dig deeper and unearth a document proving that his maternal grandmother had converted to Christianity in 1817.”

“It Should Be Outlawed”

Perhaps the greatest irony of the mtDNA testing is that its fiercest opposition is coming from the very quarters it can most help — immigrants to Israel who need to prove that they are indeed Jewish. Yet the testing has been condemned by immigration activists and left-wing politicians as a pseudoscientific development, a slippery slope that risks turning Jewishness into a genetic and racial, rather than a religious or national, identity. That’s because many “progressive” activists don’t believe Judaism should be defined by matrilineal descent, but instead where one’s heart or allegiance is.

Opponents have warned that the tests are discriminatory in that they are largely demanded by the Rabbinate for immigrants from the former Soviet Union, and that they constitute an overreach of the rabbinical courts’ powers amid what they claim to be increasingly tough standards to prove Jewishness in recent years.

Even though proponents argue that the test can only have a positive outcome, corroborating a maternal Jewish line but having absolutely no effect on disproving or disqualifying a person’s Judaism, Avigdor Lieberman’s immigrant Yisrael Beiteinu party actually took his opposition to the High Court of Justice, demanding a ban on the rabbinical courts from using genetic testing in its examinations of Jewishness. Yisrael Beiteinu has also vowed to try and pass Knesset legislation outlawing it. The Court dismissed the initial petition.

Another detractor, Dr. Shuki Friedman of the Israel Democracy Institute think tank, wrote in Times of Israel that the policy must stop, as it undermines a newer and broader definition of who can be considered Jewish. “The willingness by an official body to adopt genetic testing as proof of Jewishness marks the first step in the creation of a genetically-based Judaism and the widespread use of genetic databases,” he wrote. “Beyond the fact that the use of genetics to prove Jewishness is distasteful, it constitutes a dramatic deterioration in the way we define the Jewish people.”

Yet the protests haven’t dampened the enthusiasm of its proponents, who consider the testing an incredible opportunity to link Torah and cutting-edge science in order to help people clarify their identity.

“This can never be used to cast doubt on someone’s Jewishness,” Rabbi Litke stressed. “It can only help make the case.”

DEATHBED CONFESSION

One elderly gentleman who is ever-indebted to Rabbi Litke and Rabbi Gotthold is Yaakov Weksler, a former Catholic priest whose adoptive mother revealed his Jewish identity to him before her death. Yaakov was born in Lithuania’s Shavli ghetto, just days before the purge of the local Jewish population.

Days before the purge, his mother handed him to a Polish neighbor, and soon afterward his entire family was murdered. He was raised as a Christian and went by the name of Romuald Waszkinel. While he was bullied by his classmates for his Jewish appearance, in the ensuing years he became a priest and a respected lecturer at the Catholic university in Lublin.

Despite his success in the diocese, Weksler said that he always had a vague feeling that he didn’t belong. And then, 40 years ago, his adoptive mother told him the truth.

“His mother didn’t even remember his parents’ names, only that his father had been a tailor,” says Rabbi Litke. “Of course, that didn’t feel like much help, but a few years later Yaakov decided to look into his history and somehow discovered that, indeed, his father was Yankel Weksler the tailor. He found family members in Israel, traveled to meet them, but then went on with his life.”

At first Weksler couldn’t see himself living as a Jew, “but it was pleasant to expand his family and he visited Israel occasionally,” Rabbi Litke relates. “He even arranged that his adoptive family be recognized as Righteous Gentiles by Yad Vashem.”

But in later years, he wanted to reconnect with his source, only to find the gates of Israeli citizenship closed. He found out about Simanim, took a DNA test, and the result revealed a very high chance of Jewishness. “It revealed that he had a certain common Jewish marker that we didn’t find among non-Jews at all,” Rabbi Litke relates. “We applied to various batei din and eventually his Judaism was certified. Today he lives as a religious Jew in Jerusalem and hopes, after 120, to die as a Jew as well.”

Rachel Ginsberg contributed to this report

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 889)

Oops! We could not locate your form.