Free Agent

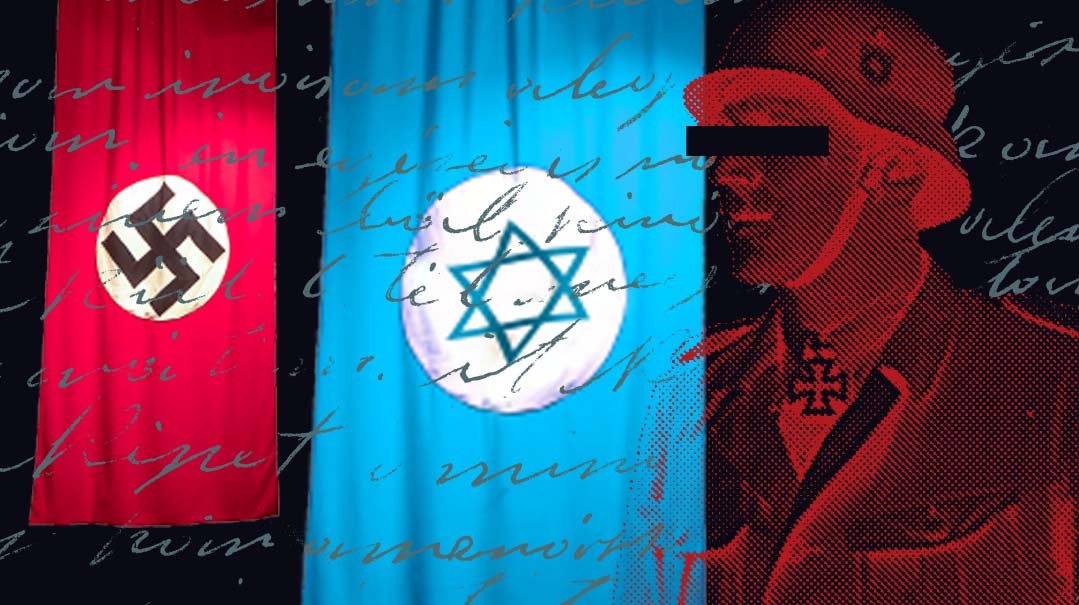

| September 14, 2021The merciless Mossad hit man with a tangled Nazi history

Photos: Mishpacha archives

How did a celebrated SS officer and unrepentant Nazi hero become a hit man for the Israeli Mossad? That is the mystery of Otto Skorzeny, a former lieutenant colonel in Nazi Germany’s Waffen-SS, leader of a unit of SS commandos, rescuer of Italy’s fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, and Hitler’s own favorite among the special operations officers. It’s also a lesson in the Mossad’s often shocking and unconventional methods for protecting Israel, especially in the early, vulnerable days of the fledgling state.

Based on interviews with former Mossad officers and with Israelis who have access to the Mossad’s archived secrets from decades ago, award-winning Israeli journalist Yossi Melman and Washington-based news correspondent Dan Raviv — coauthors of five books about Israel’s espionage activities and security agencies — uncovered information verifying that Skorzeny was not only recruited as a Mossad operative, but actually pulled the trigger on an enemy scientist as part of an Israeli espionage plot to thwart the development of Egyptian missiles targeting Israel in the early 1960s.

The Mossad mission, known as Operation Damocles, was aimed at targeting the German scientists — former employees of Nazi Germany’s weapons program — who were hired in the summer of 1962 to develop an arsenal of missiles for Egypt to use against Israel. Skorzeny, who worked with the scientists and the companies that were supplying them, was originally on the Mossad’s hit list too — until spymaster Isser Harel thought it would be better to enlist him than to kill him.

It’s not unusual for a spy ring of international reach to sometimes work with partners they’d ideologically prefer to stay away from. But while dancing with the devil was understandable from the Mossad’s vantage point, why would an avowed Nazi like Skorzeny deign to work with the Mossad?

Otto Skorzeny (pronounced Skor-tsay-nee) was born in Vienna in 1908. His father, Anton, owned a successful construction business, and both sides of the family were proud of their military affiliations: Anton would serve as a reserve artillery officer a few years later, in World War I, and his wife, Flora, belonged to an old-time military dynasty that had protected the Austrian empire’s borders for generations.

Defeat of World War I left Austria economically dysfunctional, inflation-ravaged, and deeply embittered. The new democracy was weak, supported by a poverty-stricken, largely jobless middle class. But the young, headstrong Otto Skorzeny was not deterred by adversity. Fortified with the traditional beliefs that he could restore honor to his country with cunning and courage, he relished the challenge of building his future out of the ruins.

As a teen, athletics beckoned — he had shot up to a startling 6’4”, was heavily built, and liberally endowed with muscle. An enthusiastic sportsman with good coordination, he was drawn to sports that involved weapons, and he joined the Schlagendeverbindung, the school’s dueling society. By the time of his graduation, Skorzeny had distinguished himself by winning 14 duels. During the tenth, he received the imposing “schmisse” he had secretly hoped for, a severe slash from ear to chin on his left cheek. True to the society’s traditions, it was stitched up on the spot without anesthetic. This scar became his trademark.

The upper Nazi hierarchy, with which he’d later be affiliated, sported many faces of dueling scars, considered a badge of honor. Himmler had one, and so did SS-Obergruppenfuhrer Ernst Kaltenbrunner, although he was accused of having come by his in a car accident. But Skorzeny’s was never subject to doubt — his reputation as a duelist followed him.

Skorzeny was 24 when he joined Austria’s branch of the Nazi Party in 1932. He served in its armed militia and considered Adolf Hitler his hero. He swiftly rose through the ranks of an elite branch of the SA (Sturmabteilung), known as the SS (Schutzstaffel).

In addition, Skorzeny began a career as a mechanic. Within a few years, he became the junior partner in a construction and scaffolding company after marrying the company owner’s daughter, Margareta Gretl Schreiber. Three years later, after buying a majority share in the business, he divorced her.

Hitler seized Austria in 1938, and with his invasion of Poland in 1939 and the outbreak of World War II, Skorzeny left the construction firm and volunteered for the Leibstandarte SS Panzer Division that served as Hitler’s personal bodyguard battalion.

In the ensuing months, he took part in battles in Russia and Poland, although in his memoirs, penned after the war, he denied taking part in the extermination of Jews. After spending the first part of the war occupying an eclectic selection of roles, including a transport manager, engineering officer and instructor, and SS-Obersturmfuhrer in a tank battalion, Skorzeny was pulled out of rank and deposited at the headquarters of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA — an extreme equivalent of the Ministry of Interior, with the stated goal to fight all “enemies of the Reich” inside and outside the borders of Nazi Germany).

Desperate for loyalty, Austrian-born Hitler had promoted Ernst Kaltenbrunner — a loyal Austrian landsman — to the position of head of the RSHA, and Kaltenbrunner, similarly anxious to surround himself with friends, swiftly roped in Skorzeny. There, among his responsibilities, he was instructed to train an SS commando unit.

“A big man, with big ideas and a big mouth, he was sorely lacking when it came to administrative detail and the subtle art of diplomacy,” says UK researcher and business journalist Stuart Smith, author of Otto Skorzeny: the Devil’s Disciple. Nevertheless, his big break was not long in coming.

Oops! We could not locate your form.