Improbable Mission

With his future at stake, actor Steven Hill clung to Shabbos

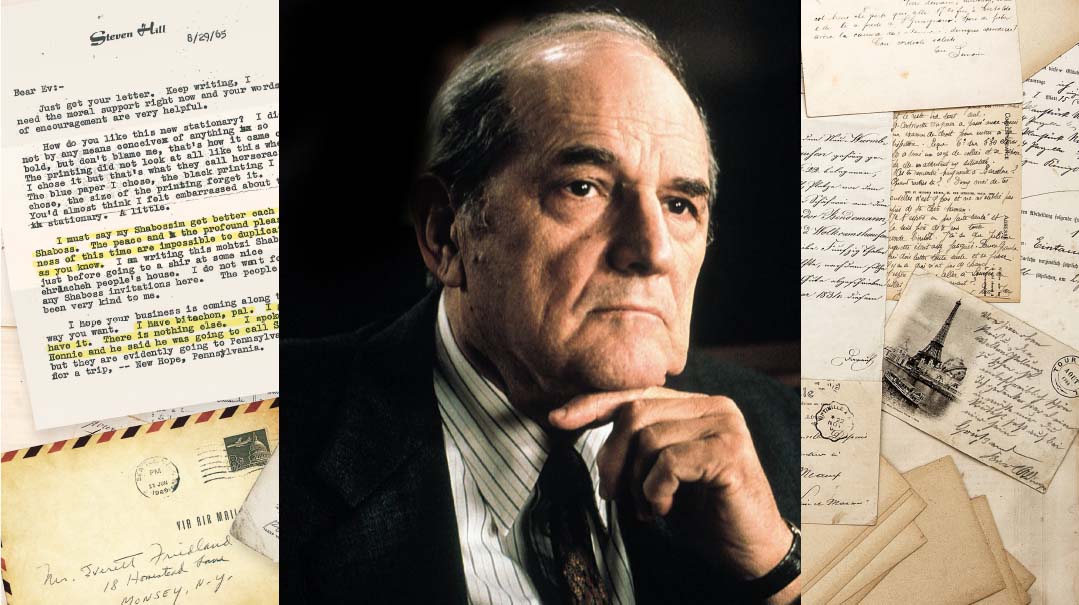

How much more can be written about Steven Hill, the famous Torah-observant TV and film actor who tenaciously clung to his principles after becoming frum in the early 1960s? The story is well-known: There were the early years of glitter and glitz and the later years of fame and kavod before his passing in 2016 at age 94. But a recently discovered cache of letters reveals something else: the darkness, brokenness, and loneliness of a man who’d been at the top of the world, who had sacrificed his career and his family for a Torah life — as he clutched onto Shabbos for sheer survival.

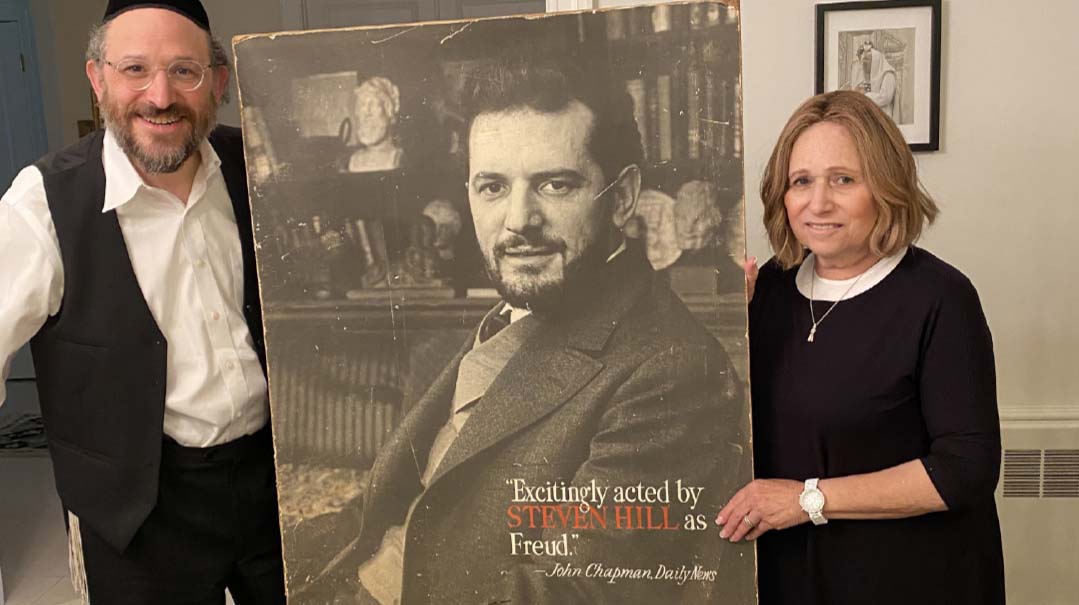

My friend Sam Friedland discovered the letters as he was going through the papers of his mother, Mrs. Rhoda Friedland, after her passing a little more than a year ago. There was an extensive correspondence, for instance, between his parents and the two most recent Lubavitcher Rebbes. But one particular cache of letters took Sam for a long trip down memory lane: It was a correspondence from 1965, between Steven Hill and his own father, Mr. Everett Friedland.

Suddenly, Sam was back in the spring of 1963, just short of his eighth birthday, playing in his front yard. Across the street, he noticed a stranger, which was a rarity for the small-town Monsey of Sam’s youth. Ever a friendly and inquisitive kid, Sam crossed the dirt path dividing his small house from that across the way and asked the stranger his name, to which he replied, “Steven.” His curiosity piqued, Sam continued with his questions:

“What do you do?”

“I’m an actor,” the stranger replied. Little Sam was sufficiently impressed with that response to grab the stranger by the hand, exclaiming, “You’ve got to come and meet my dad!” As it happened, Everett Friedland was sitting on his front porch as Sam ran up with Steven in tow and excitedly told his father that the man from across the street was an actor.

Though the actor whom Sammy excitedly escorted to meet his father was not quite a household name yet, he was one of America’s most respected character actors. And much rarer, especially for those days, he was a fairly recent baal teshuvah.

Dance of the Neshamah

Born Solomon Krakovsky to Russian immigrant parents in Seattle in 1922, Hill had been bitten by the acting bug from age six, when he played the Pied Piper of Hamelin in a school play. Intelligent, good-looking, and blessed with a sonorous voice, he had all the tools necessary for his chosen craft.

After finishing college and a four-year stint in the navy during World War II, Solomon, soon to be renamed Steven Hill, headed east, first to Chicago and then to New York City, to seek his fortune as an actor. His first role on Broadway was in a Ben Hecht play, A Flag is Born, advocating for a Jewish state in Palestine. (Hecht, a leading Hollywood screenwriter, had written the script as part of a series of pageants mounted by the Revisionist Zionist Bergson Group to call attention to the extermination of European Jewry. Unfortunately, the mainstream Zionist organizations caused the popular pageants to be shut down, rather than allow the Bergsonites to succeed in pushing the United States to make more strenuous efforts to save doomed Jews.)

Martin Landau, who would later star with Steven on Mission Impossible, remembers that in the late ‘40s there were two young actors who generated the greatest buzz, and when asked to choose who would be the biggest star, said Landau, “Steven would have been the one — he was legendary. Nuts, volatile, mad, and his work was exciting.” Strasberg later described him as one of “the finest actors America has ever produced.” During the “golden age” of television, when companies were eager to produce original dramas for TV, Steven Hill was in constant demand.

Yet, despite being well on the way to success in his chosen profession, Steven was still looking for something more in life. As with any baal teshuvah, the question of what drove him to ultimately upend his entire life must remain a mystery. And in the case of Steven Hill, it is an even greater mystery, because he had no models before him. The entire baal teshuvah movement was at least a decade in the future. There was no Rabbi Meir Schuster to approach him and inquire whether he would like to learn more about his Judaism. And had he answered affirmatively, there was as yet no Ohr Somayach or Aish HaTorah to introduce him to Jewish learning.

Nor was he like the next generation of searchers, many of whom took off a few years after college to find themselves while backpacking around the world. By the time Steven took his first halting steps toward religious observance, he was already 40 years old, married, and the father of four children.

At the very most, we have a few hints at what drove him in his spiritual search. Most of them he shared with Rabbi Mayer Schiller, a younger devotee of the Skverer Rebbe, whom Steven — or Reb Shlomo as he was always known in New Square — enlisted to help work on his autobiography.

Filming a pilot for a new TV detective series in the late ‘50s, the script called for Steven to drive down the steep incline from San Francisco’s Nob Hill at night. The only light for the scene came from a trailing car. Despite repeated attempts to get the lighting right, at the end of the evening, the director told Steven they would have to try again the next evening. Years later, he told Rabbi Schiller that the experience made him wonder whether his life amounted to anything more than driving endlessly down a hill.

Shortly thereafter, he went to visit his parents in his native Seattle. The places that he remembered from his childhood had changed, as if the anchor of his childhood had been wiped away. On Shabbos morning, however, his father asked him if he wanted to accompany him to the Orthodox shul, where he’d occasionally davened in his youth. There everything seemed exactly as it had been. The old intricately-designed aron kodesh was still there. The carpet was the same. Even the old men davening might well have been the same as the old men of Steven’s youth. This is eternity, he thought to himself.

The hint that Steven discussed most in later years came about through a slight change in a script. Hill was chosen to play Sigmund Freud in A Far Country, a production destined for Broadway. During out-of-town previews, the play’s author. Henry Denker, a one-time yeshivah student, made a slight change in the script. In the original version, a patient angrily tells Freud to stop with his probing questions. In the revised version, she tells him to stop and shouts at him accusatorily, “You are a Jew!” That line always drew a gasp from the audience, and after a pause, Freud would answer, “Yes.” Over time, Hill found that exchange echoing in his ears for hours after every performance. “Yes,” I would say to myself, “Yes.”

It was while performing in that play, that Steven and a friend first stumbled into New Square, an exclusively chassidic enclave, to which the first residents moved in 1956. Shortly after that first visit. Steven went back by himself for what turned out to be Simchas Torah and became entranced by the sight of the Skverer Rebbe, Rabbi Yaakov Yosef Twersky, dancing.

Asked afterwards to imitate the Rebbe’s dancing, he replied that he could not. Everyone, he explained, has a bit of falsehood or showmanship in how they move or present themselves. And that is what an actor picks up on when he imitates that person. But in the Rebbe, he had been unable to find anything false that could be imitated. All was holiness. “He danced with his neshamah, not his body,” Steven would say later.

In time, Steven met the Rebbe personally and found himself powerfully drawn to him and to Orthodox Judaism.

Letters of Faith

The circumstances that brought Steven Hill to Monsey that spring day Sammy met him weren’t happy ones. He’d rented a room across the street from the Friedlands because, not surprisingly, his seemingly out-of-the-blue decision to become an observant Jew had not been taken in stride by his family. He was facing the end of his marriage, as well as the potential loss of any ability to affect the future religious development of his children.

If there was one thing he needed at that point in his life, it was a friend with whom he could speak things out. And Everett Friedland would turn out to be the perfect friend.

“My father and Steven Hill established an immediate rapport,” Sam remembers. My father was well-educated, had a photographic memory, and shared Steven’s love of Shakespeare. He and Steven would often toss back and forth lines from various plays of Shakespeare, and at one point, they even set out to write a script together.”

It likely helped cement that relationship that Everett had suffered some recent business reversals and also needed someone with whom to share his concerns.

And before their first conversation was over, Everett told his new friend that there was no need for him to rent an apartment across the street: The Friedlands had a room in their basement, and Hill was welcome to stay there as long as he wanted without rent. And that is what he did over the next two years — with intermittent breaks when acting jobs drew him away from Monsey.

Everett also introduced Steven to chess master Samuel Reshevsky, another nearby Monsey resident. Already at the age of four, Reshevsky was recognized as a chess prodigy in his native Poland. He was an eight-time US chess champion, and over a 30-year span from the mid-‘30s to the mid-‘60s, a leading contender for the title of world champion. The three men gathered at least once a week to play ping-pong and talk.

At the shivah house for Everett Friedland, nearly 50 years after they first met, an already aged Shlomo Hill entered. “He started to speak about my father, but he just couldn’t,” says Sam. “He just put his head down and cried for half an hour, before arising to offer tanchumim.”

Hill did not abandon his family, who lived in Skyview Acres, just a ten-minute drive from Monsey. Over the two years that Steven lived with the Friedlands, his wife came to speak frequently to Mrs. Friedland. But in the end, the changes she felt would be required were beyond her. “I didn’t choose this life,” she told Mrs. Friedland. The marriage was unsustainable.

For a period of time, the Hill children were enrolled in the Yeshivah of Spring Valley. The oldest boy, Johnny, was approximately the same age as Sam, and one of Hill’s first comments to Sam was to express the hope that he and Johnny would become friends. Indeed, that did happen. Over the next two years, Sam played frequently with the Hill children, both in his own home and at theirs. He remembers being at Johnny’s bar mitzvah at Monsey’s Bais Israel shul. Those in attendance were shocked that the son of a famous actor leined the haftarah so well.

In the summer of 1965, Steven decided that he would have to relocate, at least temporarily, to Los Angeles to seek movie roles in order to support his family. It was during that time that he wrote the letters to Everett Friedland that Sam found among his mother’s papers. Those letters provide fascinating insight into the thoughts of a man having made a life-altering decision as he struggled with the consequences of sticking to his convictions. In a letter dated September 9, 1965, he wrote Everett that

“the offers, baruch Hashem, are coming, but Shabbos [sic] cancels them out. It is as if it were some kind of a contest as to how long I can hold out or how many more will come. The latest “almost” offer was the most I have ever been offered in my career and is in the regions of the big-name stars — but Shabbos so far has prevented this concrete offer. Two days ago they said absolutely not, they were sorry but I was being strongly considered but it was impossible. Yesterday they came back to my agent and they asked if I was really serious about this thing, and couldn’t I get some sort of dispensation from a rabbi. Well, I laughed over the phone, but when I hung up I did not laugh. I said a kapittel Tehillim.”

The movie went on to both box office and critical acclaim.

The time in Los Angeles was not a total disaster though. A month before, he’d reported to his friend that he landed at least one movie role, and that that the film was supposed to be good, but that he had not yet seen it “so I can’t say.” He did not “want for Shabbos invitations,” and added that “my Shabbosim get better with each Shabbos. The peace and the profound pleasantness are impossible to duplicate.”

Still, in a letter dated August 19, he wrote how he

“lost two big jobs… so far because of Shabbos. One job was a film in Utah, on location, where they work Saturday. The other was a guest shot on a TV show, where they scheduled work Friday night. It would be stupid of me if I didn’t admit that hurt, but the compensation of Shabbos, who can measure it. No job is in sight right now, but I thank G-d for what I have.”

In another letter, after inquiring about the state of Everett’s business, Steven wrote,

“I have bitachon, pal. I got to have it. There is nothing else.”

Besides his job prospects, the other major topic of Hill’s letters was his children. It was clear that he was in frequent touch with them and very involved in their lives. He was particularly eager that his son Jonny’s friendship with Sammy Friedland’s continue to blossom. In June of 1965 he wrote,

“Jonny writes me that he’s been talking to Sammy and trying to make arrangements to meet, which of course pleased me very much, I hope they can become friends, which would please me more — and that we could move to Monsey — all of us, which would be the most wonderful of all — even with all the imperfections.”

Two weeks later, he reported how delighted he was to have heard

“about Jonny and Matt [his second son] coming over and playing with your boys, and Jonny sleeping over. I hope he didn’t give you too much trouble…”

And he reported to his friend that “Jonny says Sammy knows a lot of Torah.”

While he still expressed a desire to return to New York, especially if “I might land a steady project in NY, like a series, but I think it’s mostly a hope at this point,” in the meantime, he had to face the reality that most of his jobs over the preceding three years had come from Hollywood.

What’s a Million Dollars?

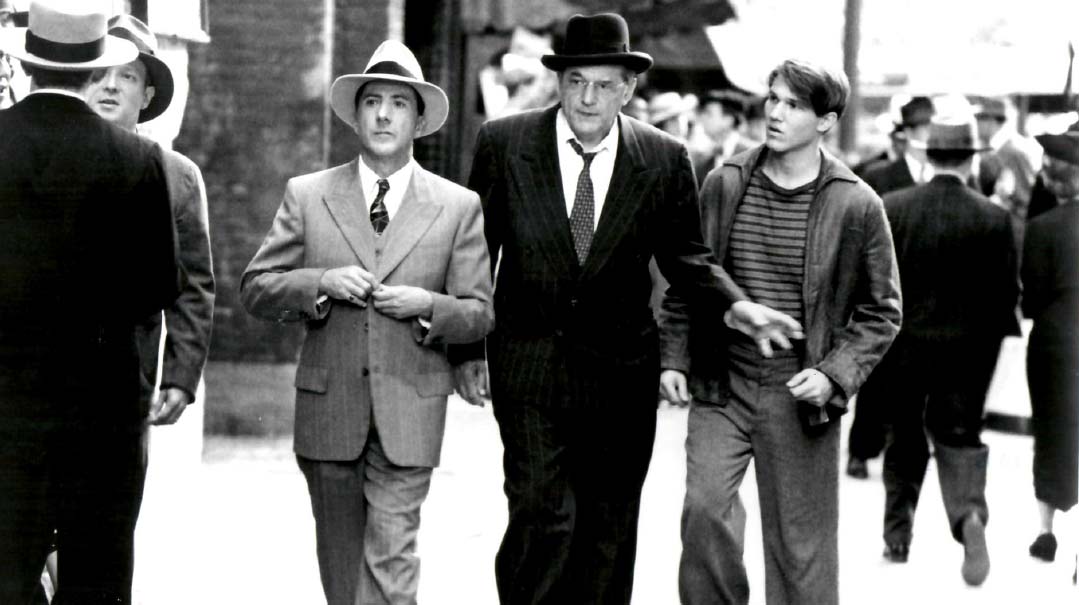

The hopes of obtaining a role in an ongoing series were soon realized, however, when Steven was selected to play the team leader in a new TV drama, Mission Impossible. The action show was an immediate hit and would last for nine seasons. When the first episode aired, the Friedlands located a color TV in Monsey to watch, together with Steven, who had returned from the West Coast.

“Steven told me that I could sit on his lap but that I couldn’t ask any questions until the show was over,” Sammy remembers.

Steven’s refusal to work on Shabbos was explicitly included in his contract (as was a provision against his being asked to wear any garment containing shatnez). Yet as the implications of Steven’s Shabbos observance became clearer to the producers of Mission Impossible, his role was whittled down, and his contract was not renewed for a second season, despite the stamp he had put on his character.

During his dispute with the show’s producers, Steven did have at least one supporter: the famous TV comedienne Lucille Ball. At the time, she owned the production company that produced the show. Ball, a religious Christian, invited Steven to her home and told him. “You should stand up. I’m fighting with them. I’m fighting with them.” Apparently, her efforts were not enough. In any event, Steven was starting on a new chapter in his life, which would be incompatible with continuing with Mission Impossible.

In 1967, Steven Hill married Ruchi, a younger woman he met at a Monsey Shabbos table. When she told her father, Rabbi Yehoshua Leib Shenker of Baltimore, that there would be an actor at their cousin’s Shabbos table, she also had to provide some explanation of what an actor was to her father. But after meeting “the actor,” Reb Yehoshua Leib, the grandson of Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, blurted out to his daughter in Yiddish, “But he looks like a yeshivaman.” Still, Ruchi’s father was concerned. Yet when he consulted with the Skverer Rebbe about the shidduch, the Rebbe told him, “He has passed through so many nisyonos, you have nothing to worry about.”

For the first ten years of marriage, Hill did no acting, except for a voice-over narration of a documentary about Israel’s birth. Now, for the first time, he was able to catch up on all the Torah learning he had missed out on in his youth and to savor being a father to young children again — five in all. During that time, he tried his hand at various ventures, including diamonds and real-estate, none of which were especially successful.

In 1977, the need to support his family sent him back to acting — he felt that his creative juices had been rejuvenated by the time away. It wasn’t simple to break into that competitive world again after a decade’s absence, though, especially with his religious strictures, and so he started out taking commercials and bit parts. But his star rose again, and between 1977 and 1993, he appeared in 17 films.

At one point, he was offered one million dollars to work on a film, but they weren’t giving an exemption for Shabbos. His son Reb Yonason, a musician with a large family in Jerusalem, asked him at the time why the producers had done such a thing, given that everyone in the industry knew he had not worked on Shabbos in 25 years. “It wasn’t them. It was Hashem giving me a booster shot,” Steven replied.

Then in 1990, he came into the role for which he’s best remembered — he was cast as a crusty Manhattan DA on the TV show Law and Order. Law and Order would become one of the longest-running shows in the history of television, besides generating numerous spin-offs. His character was loosely based on Robert Morgenthau, the long-time Manhattan DA and the son of FDR’s Treasury Secretary, Henry Morgenthau, the only Jew in Roosevelt’s administration to continually push for the rescue of Europe’s Jews.

Dick Wolf, the show’s creator, described Hill as “the Talmudic influence on the entire spirit of the series… Not only was he one of the very great actors of his generation, he was one of the most intelligent people I have ever met.” Most important, Wolf added, “He has more moral authority than anyone else in television.”

The Gift Lives On

Steven Hill knew that he had been blessed with a gift. One time, he asked Sam Friedland to drive him to a recording studio in New Jersey to do a voice-over for a video for the Bikur Cholim of Rockland County.

“When we arrived,” Sam relates, “I wanted to get a cup of coffee, and asked the technicians how long they estimated it would be. They assured me that at least three takes would be needed, and it would take at least an hour. But when I came back 15 minutes later, Reb Shlomo was already finishing, much to the amazement of the recording technicians. The very first take had gone perfectly.”

The only person who was not surprised was Hill himself. As he explained to Sam, he had been blessed by Hashem with a certain gift.

In general, Reb Shlomo preferred to keep things compartmentalized between his acting and the rest of his life. For instance, he never brought his children to visit him on the set of a movie or of Law and Order. According to his son Reb Yonason, “He’d have Shabbos guests who would try to draw him into a discussion about what would happen in the next episode, or young people who sought his advice about breaking into the field. He’d tell them, ‘It’s a dirty business, better to stay in the beis medrash.’ And he was always learning — in the trailer, during breaks in the shooting. He finished Shas three times.”

He even came to believe that his acting improved as it became less and less important to him. As he came to view acting as just a means of earning a living doing something he enjoyed, he felt released from the pressure of deriving his sense of self-worth from his acting talents. That would come from his relationship with the Eibeshter.

But the crew and his fellow actors never forgot that they were in the presence of a deeply committed Torah Jew. Their language and comportment were completely different when he was present. He was never abashed about being an Orthodox Jew, even at the beginning of his journey. Indeed, one day during the first year of filming Mission Impossible, William Shatner, the star of Star Trek, burst into the office of the studio executive, Herb Solow, and announced that Steven had called from the set of Mission Impossible saying that he needed another four Jews from Star Trek for a minyan, including Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, associate producer Robert Justman, and Solow. That same year, Steven invested effort in trying to convince two of his costars, the married couple Martin Landau and Barbara Bain, to kasher their home.

During the filming of Billy Bathgate, Steven and star Dustin Hoffman became quite friendly. A short time later, Hoffman was doing a one-man show on Broadway and sent Steven and Ruchi tickets. After the show, they went to visit Hoffman in his dressing room. Turning to Mrs. Hill, Dustin Hoffman told her, “Steven knows what to do with his life. The rest of us don’t know.”

In time, Reb Shlomo had the satisfaction of seeing his children and grandchildren, who had inherited various aspects of his gifts, finding multiple ways to put them to the service of the Eibeshter as well. There is a strong musical gene in the Hill family. Reb Shlomo himself played both the piano and French horn, and a number of his children and grandchildren have made their careers as professional musicians. His son Yonason’s son Ari Hill has already achieved renown in the world of Jewish music, and Ari’s younger brother Yanky is also gaining a growing following.

The family recently collaborated on a special album called V’Nafshi, based on 10 niggunim composed by Dovid Hill a”h, the ninth of Reb Yonason and Leah Hill’s 13 children, prior to his passing just short of his 14th birthday. On five of those tracks, Dovid is the primary voice (while young Dovid was alive, Reb Yonason decided to take him to the studio and record his golden voice), even though he had to teach himself to sing again after a tracheotomy by pressing his finger to close off his windpipe. The niggunim all accompany familiar pesukim that resonated particularly with Dovid during the final seven years of his life, as he endured chemotherapy and bone marrow transplants in the hope of curing his leukemia. The young boy with the ethereal voice — described by the late Tosher Rebbe as straight from the heichal haneginah — shares his own fears, hope for a cure, and trust in Hashem in niggunim he himself wrote, that will bring solace to many others who find themselves in similar situations. His legacy is secure and is part of his grandfather’s as well.

Reb Shlomo did not live to hear V’Nafshi, but he was able to savor the emergence of his son Reb Yehoshua Leib — Rebbee Hill — as one of the most prominent storytellers of the generation, employing the same dramatic skills and voice as his father. Rabbi Tzvi Zev Schwartz, a well-known Lakewood educator, describes Rebbee Hill as “one of the few who can control a thousand kids with a story.”

Of Rebbee Hill’s many styles of tapes, the ones that his father enjoyed most were the simple, straightforward storytelling, modeled on the style of Reb Leibel Weinstock a”h, a master storyteller and one of the mispallelim in the Monsey shul in which Reb Yehoshua Leib grew up. After listening to his son’s Eliyahu B’Har HaCarmel, Reb Shlomo pounded the table in excitement, “This, my boy, is the real thing. This is real entertainment.”

No words could have been sweeter to Reb Yehoshua Leib, who first started thinking about children’s tapes after hearing Rabbi Akiva Tatz on a tape intoning, “What is broken? What talents do you have to fix it?” He decided that what was broken was the lack of material for frum children that both entertained and instilled positive messages. And the very talents that he had inherited from his father were what he could use to fix the problem.

Rabbi Mayer Schiller, who was close to Reb Shlomo for close to 50 years, says that the most astounding thing about him was that over more than half a century — from his first entry into New Square — his enthusiasm and excitement about every aspect of Torah life — tefillah, learning, Shabbos — never waned in the slightest: It only grew. And now he is shepping nachas in Shamayim, not only from his own considerable kiddush Hashem but from the manner in which so many of his offspring are using the gifts he nurtured in them.

In the early days of his journey, during those heartfelt letters and deep conversations with his new friend from Monsey, he grappled with the ramifications of his commitment, clinging to Shabbos against all odds. He couldn’t have known then how life would turn out for him and the Jewish talent empire he was to build, but one thing he knew: “I have bitachon, pal. I got to have it. There is nothing else.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 878)

Oops! We could not locate your form.