A Tag and a Price

New European Union labeling guidelines mean that Israel will be isolated and punished like no other nation on Earth. The Europeans call it a technicality. Others see a dangerous step toward adoption of the boycott movement’s goals

T

he new European Union labeling requirement that brands Israeli products originating in “occupied territories” with the Mark of Cain may only affect a tiny fraction of the Jewish state’s exports, but that is no consolation whatsoever to Chanan Pasternak.

For most of his 40 years as a farmer, Pasternak exported 80 percent of his peppers, dates, grapes, and eggplants to Europe from his farmland on Moshav Netiv Hagedud, about 12 miles north of Jericho. He is a pioneer in the Jordan River Valley, where farmers labored to convert the salty, chemical-rich earth of this region just north of the Dead Sea into a fertile crescent. Annual agricultural exports now total NIS 700 million, or about $180 million.

It’s been a challenging year for Pasternak, who is still reeling from two major blows. Terrorists killed his business partner, Avi Ben Zion, when they ambushed him at a junction in Samaria, stole his car, and ran him over with it. Then, flooding wiped out 50 percent of his main crop, green peppers. The latest blow is the ill wind emanating from the EU’s labeling requirement, which might force a portion of his crops to rot on the vine unless he can find new markets fast. His only remaining customer is Russia, where demand is currently weak.

Standing tall amid the rows of green peppers as big as a man’s two fists, his mood was clearly somber.

“I can’t change professions at my age,” Pasternak says. “If I have to shut my operation, I’ll survive financially.”

But he can’t say the same for the 100 Palestinian workers he employs, some of whom cried at the grave of his martyred partner after Ben Zion was buried.

“Most of them have no other employment option. They’re the ones who are going to starve.”

Israeli exporters based in Yesha (Yehudah and the Shomron) and Palestinian workers both stand to lose following European Commission adoption last Wednesday of new guidelines under which exports originating in Yesha, including east Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, can no longer be marked “Made in Israel.” Instead they must be labeled: “product from the Golan Heights (Israeli settlement)” or “product from West Bank (Israeli settlement).”

The European Commission termed this “an interpretative notice” whose aim is “to provide Member States, economic operators and consumers with the necessary information on the indication of origin of products when it comes to products originating in Israeli settlements beyond Israel’s 1967 borders.”

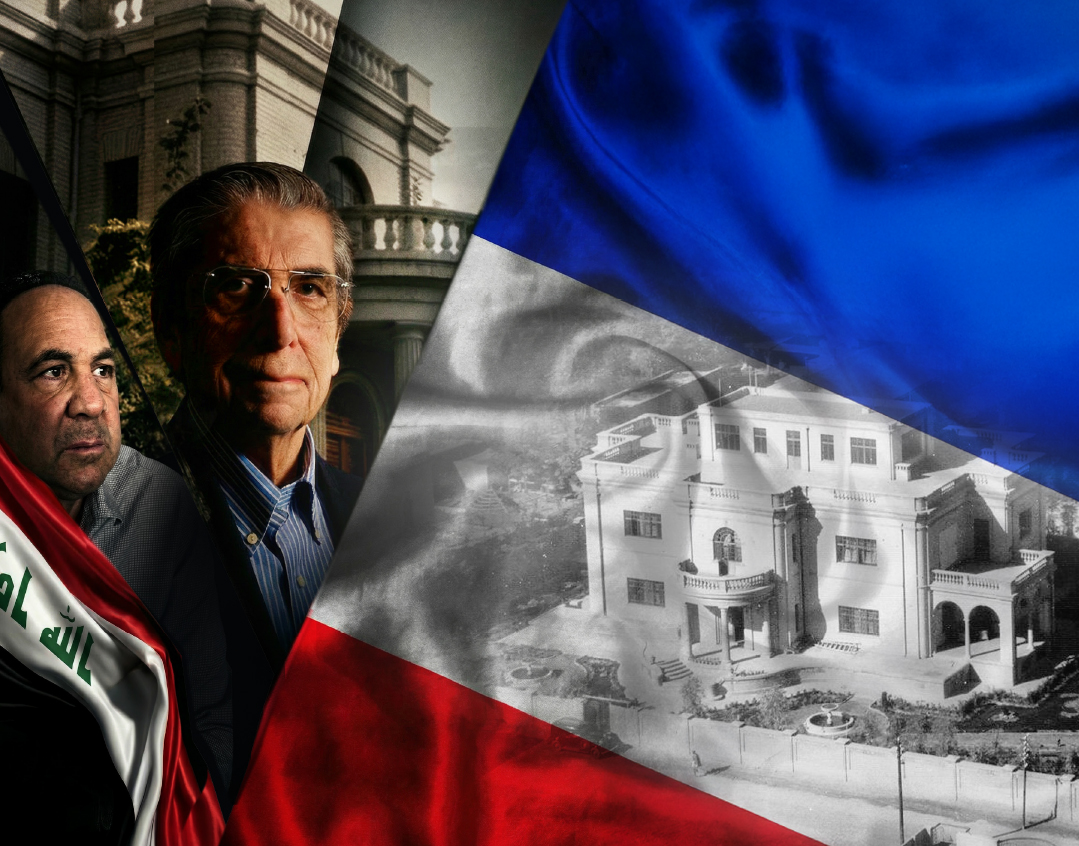

David Elhayani, mayor of Jordan Valley Regional Council, says that the new labeling requirements serve only one purpose: “To put their finger on the product and say there’s something wrong with it. Don’t buy it.”

“This is not a boycott,” said Lars Faaborg-Andersen, the European Union’s ambassador to Israel at a Jerusalem news conference. “These products are still very welcome in the European market. They just have to have the correct markings on them.”

Requirements for such markings, or “rules of origin” (ROO), have been written into European-Israeli trade agreements since 1995, and are a standard clause in European trade agreements with 35 other nations. These markings have economic benefit when used to inform consumers of a product’s origin, or even if it’s been genetically modified. Importing countries also use them to determine proper tariffs and to tabulate up-to-date trade figures.

But the new standard has a political connotation applied only to Israel and not to any other conflict zone or disputed territory in the world.

“There is no doubt that the main purpose of the measure is to exert political pressure upon Israel,” said Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu in a press statement. “It is simply a distortion of justice and of logic and does not advance peace. The root of the conflict is not the territories, and the root of the conflict is not the settlements.”

Dates and Figs

For once, Netanyahu enjoyed a rare show of across-the-board domestic political support. Zionist Union leader Isaac Herzog labeled the EU decision “a prize for terror” and Yesh Atid head Yair Lapid accused the EU of “capitulating to the worst elements of jihad” while “hiding behind legal jargon.”

Netanyahu can’t say the same for the Obama administration. Despite the positive tone of his meeting with the president earlier the same week, State Department spokesman Mark Toner issued a statement saying: “We do not consider settlements to be part of Israel. We do not view labeling the origin of products as being from the settlements as a boycott of Israel.”

A bipartisan group of 35 US senators, led by Ted Cruz (R–TX) and Kirsten Gillibrand (D–NY) sent a letter to EU High Representative Federica Mogherini opposing the EU measure.

Reached for comment in Washington, Sen. Cruz sent Mishpacha a statement through his press secretary Phil Novack expressing his disappointment at what he called “a de facto boycott of Israel.” Sen. Cruz described it as an “ill-informed move that will not only undermine any future prospects for a negotiated settlement between Israel and the Palestinians, but also reinforces the impression that anti-Semitism is on the rise in Europe. The timing of this move is particularly unfortunate given that Israel is currently enduring a new wave of Palestinian terrorism largely unrebuked by the EU.”

While the new labels may cause more European consumers to shy away from Israeli exports, Israeli officials insist the overall impact on the 30-billion-euro annual Israel-EU trade will be minimal. Products produced in the territories amount to just 0.1 percent of Israel’s exports.

Threats of a European boycott on Israel’s agricultural sector have been building since 2009, when the UK first introduced dual labels for food produced in Israeli settlements and the Palestinian West Bank. Denmark and Belgium followed with similar guidelines in 2013 and 2014.

Up until now, some Israeli companies operating in Yesha have bypassed EU scrutiny on product origin by using the services of overseas facilities and distributors, or exporting indirectly through a third country. Others use different labels for its exports that don’t identify their “offending” hometown.

But sometimes, Israeli chutzpah is insufficient. Many agricultural operations in the Jordan River Valley have nonetheless suffered from the moves of European countries until now and have had to scurry to find new customers.

“Ten years ago, I shipped all of my exports to Europe, but now, only 60 percent goes there,” says Avigdor Arbel, proprietor of Meshek Arbel in Masuah, just west of the Jordanian border. Meshek Arbel is a leading packager of fresh Medjool dates since 1974. Israel supplies some 50 percent of the world’s Medjool dates, a delicacy that Muslims often use to break their fasts during Ramadan. Arbel says he has been fortunate to find new markets, and sometimes, the old customers come back.

Two years ago, Tesco, a major retailer with more than 3,500 retail outlets in the UK alone, told Arbel not to ship his figs because buyers were boycotting them. Arbel found another buyer. “Two weeks later Tesco called me back and said, ‘We need figs now, please ship them.’ I said, ‘Too bad, I already sold them.’ ”

As Arbel surveys his plant this day, the conveyor belts are whirring. Dates roll up and down the metal slides, falling into five-kilo boxes for shipment as if nothing’s happened. Arbel is defiant in the face of the new labeling requirement. “They can’t pressure me through boycotts. My dates can survive for a year in storage.”

About a dozen Arab workers man the conveyor belt, including a 19-year-old from the nearby Arab village of al-Jiftlik, who asks reporters to call him “C.”

“C” can’t afford to be seen, or named. In the past, Arab workers photographed or otherwise identified in the media as working for Israeli employers have been threatened, or worse.

“C” attended a UN school in the area, so he did not grow up with exposure to the incitement that drips off the ink of Palestinian Authority schoolbooks. He began working for Arbel 18 months ago. Speaking through an interpreter, “C” says every able-bodied worker in his village works for Israelis.

“If I had a choice to work for an Arab or an Israeli employer, the only thing that would make a difference to me would be the conditions,” C said. “I work for Avigdor [Arbel] because he’s a good man and he takes care of me.”

Silent Boycott

While “C” is one of 6,000 full-time Palestinian agricultural workers in the Jordan River Valley, that number doubles during the harvest season. Overall, some 30,000 Palestinians work in the approximately 136 Jewish-owned businesses in Yesha and the Golan, according to Who Profits, an Israeli NGO that monitors industry in the territories. The majority of these companies (94) have headquarters inside Israel’s pre-1967 borders. Only 29 are exclusively headquartered in the territories, while six are, ironically, production plants of European concerns from Belgium, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and the UK.

These business are about equally divided between agriculture, construction, and low-tech manufacturers, along with some banks and transportation companies.

But agriculture is the mainstay for the area’s Jewish population.

Some 7,000 Jews — 1,500 families — live in the 21 communities that make up the Jordan Valley Regional Council. Of the 1,500 families, 900 are farmers.

Yinon Rosenblum, 56, of Moshav Na’ama, grows spices. He must pick, pack, and ship his fresh basil, tarragon, oregano, mint, and rosemary on the same day to avoid spoilage.

Moshav Na’ama is the closest Israeli town to the Jordanian border. Its secondary service road is lined with barbed wire and signs warning of land mines. Sensors and security cameras are outfitted along the fence to warn of potential infiltrators, although today the only break in the routine was a flock of goats that blocked the road for a few short minutes.

Perhaps they’re attracted to the aroma of the basil, like me. As I bend over the rows of basil in Yinon’s greenhouse to make the brachah of Borei isvei besamim, Yinon crouches to pick up a clod of rich brown earth from underneath the nylon that carpets his hothouse.

The dirt barely resembles the scorched earth he found upon his arrival in 1982, after impulsively leaving his hometown of Haifa after his IDF service, and exchanging big-city comforts for a caravan without air conditioning in a region where summer daytime temperatures rarely dip below 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

“I was young and stupid,” Yinon says, but the sense of adventure overwhelmed him. Back then, he says, it was truly the New Middle East. The closest bank was located in Jericho, so while taking care of business, he would often sit with the local Arabs, sip coffee, and smoke nargila.

“They all told me the same thing,” Yinon says. “After a year, you’ll be out of here because no one can grow anything here.”

He could see their point. The water supply was insufficient to support agriculture and the soil was barren. But he set out to prove them wrong.

The Israeli government launched a pipeline project to carry sewage water from Jerusalem into local reservoirs. Pumping and filtration stations were built to separate the water from the waste. The sediment that settled at the bottom of the reservoir was used for compost, and the clean water for irrigation.

“For my first five summers, we had to wash out the soil, which was full of salt and chemicals, 50 to 70 centimeters down [about 20 to 30 inches] to where the roots reached. We repeated the process until we washed all the salt out. Now, the constant drip irrigation keeps the surface dirt saturated so whatever salt is at the bottom doesn’t seep to the top.”

Rosenblum can’t return to Jericho to say “I told you so.” Jericho is now part of Area A, under full Palestinian control since the Oslo accords, and off-limits to Jews. But Yinon’s son Gil, 31, has continued his father’s tradition, sipping morning coffee on the farm with one of his Arab workers.

“We don’t discuss politics,” Gil says. “We talk as friends. We’re about the same age and going through similar life experiences. He’s worried about his job. He doesn’t want to find himself without one.”

Does Yinon worry his exports will plummet with the implementation of the new EU guidelines?

“I don’t know,” he says. “I hope it will have no effect. For me, this isn’t occupied territory, it’s Israel. This is my homeland. This isn’t like a shop that I can just close and move elsewhere. The Palestinians want to force a solution on us without talking and the Europeans want a silent boycott. They don’t want us to be here so they’re putting pressure on us. What I want them to do is buy the best produce, and choose what’s best for them, just as if they were comparing tomatoes from Spain or Morocco, without injecting politics into it.”

Worse than Hypocrisy

Taking the politics out of the economic equation in the Middle East will be more challenging than it was for Yinon to wash the salt out of his soil.

As early as 2001, British newspapers such as the Telegraph and the Guardian began quoting unnamed EU diplomats who said that new labeling requirements were one tool at their disposal to coerce Israel to change its policies in the territories, or even to strip Israel of privileged trade access as a punishment for its alleged ill treatment of the Palestinians.

Citing these quotes in the 2015 winter edition of the Middle East Journal, Professors Neve Gordon and Sharon Pardo of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev wrote: “Hence, it appears that the motivation for implementing the ROO was not merely due to ‘technical reasons,’ but also as an instrument for advancing European foreign policy; in this case, as a form of EU political conditionality in order to pressure Israel to stop fortifying its settlement project in the territories.”

Questioned on this topic, Ambassador Lars Faaborg-Andersen told reporters: “This policy has its own timeline with no connection to the situation here. This notice does not express new policy or new initiatives. It’s a compilation of already existing legislation in the EU [regarding] origin of product, the intention of which is to ensure that consumers know the origins of the products they are buying in retail stores.”

This reporter pointed out that Israeli farmers had already reduced their exports to Europe because of such policies and that those moves had limited consumer choice by reducing the availability of quality products. Couldn’t that combination ultimately lead to less competition and higher prices for European consumers?

“It’s not like a warning sign that’s on a cigarette package, saying this product is hazardous to your health,” the ambassador said. “They [the settlement products] will still be available on the supermarket shelves. The only difference is they will be marked correctly, with an indication of origin.”

Under further questioning, the ambassador admitted that this is the first time the EU has applied a labeling requirement to a territorial dispute. “And the reason why it’s the first time, is because in our view, there is no comparable situation that would have warranted a similar exercise on our part.”

But many experts in international law and media critics disagree.

Take the Western Sahara. Formerly a Spanish colony, Western Sahara is now a disputed territory claimed by both Morocco and the Polisario Front, a proxy for Algeria.

Neither the UN nor the EU recognize Morocco’s claims to the Western Sahara. The Guardian reported that sweet mixed baby tomatoes sold by supermarket giants Tesco and Morrisons have been labeled as produce of Morocco when in fact they were from giant agribusinesses in Western Sahara, some owned by Morocco’s wealthy King Mohammed VI, others by powerful Moroccan conglomerates or French multinational firms.

“Western Sahara is a different case because according to UN terminology it is a non-self-governing territory currently administered by Morocco,” Ambassador Faaborg-Andersen contends. “It’s Morocco that has to take it to self-determination, which means organizing a referendum to decide if wants to be independent, part of Morocco or Algeria. This is not a situation that’s comparable to the West Bank or the Golan Heights.”

“It’s the exact same situation,” argues Eugene Kontorovich, a professor at Northwestern University School of Law, and a senior fellow at the Kohelet Policy Forum in Jerusalem. “UN resolutions say Western Sahara is occupied and the Europeans say it is. No European country or international law recognizes Western Sahara as part of Morocco.”

While the EU is requiring products coming from an Israeli settlement to be labeled as a settlement product, the new guidelines will allow Palestinian exports from the West Bank to be labeled as either “product from Palestine” or “product from West Bank (Palestinian product).”

“You can label an item ‘product from Palestine’ even though the EU doesn’t recognize a nation of Palestine,” Kontorovich notes.

Is this hypocritical?

“It’s worse than hypocrisy — it’s actually a legal violation, because the law requires consistency,” Kontorovich says.

For now, the EU ambassador says there will be a “grace period” of “a matter of months” until the new labeling requirement come into force to allow time for customs authorities, importers, and retailers to learn the new regulations. The ambassador also noted the regulation doesn’t become official until it’s published on the EU’s official website.

In a conference call with reporters, David Simha, president of the Israeli-Palestinian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, called the new requirements a mistake. “It’s a game of playing into the hands of the BDS movement, which is probably very happy because they feel they have achieved the first stage of their boycott plans.”

Nevertheless, he hopes the lag time the EU ambassador described above will also give Israel time to reorganize a new diplomatic effort to turn the guidelines back. “I am hoping this is something that will keep everyone busy in the next few days and slowly will disappear in one way or another.”

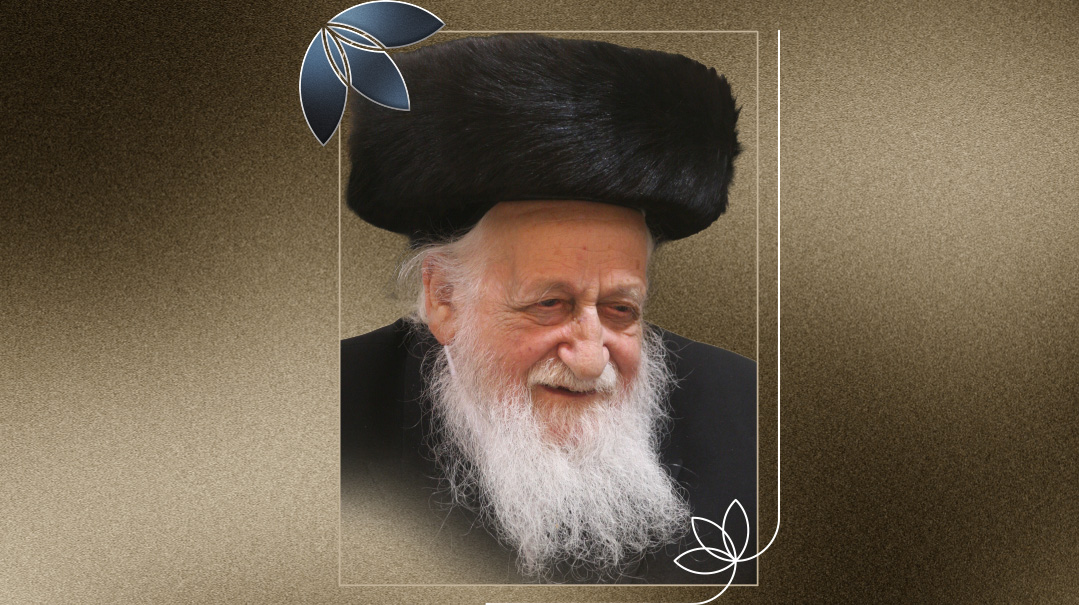

Following a meeting in Athens last week, where discussion of the labeling requirement and its relation to anti-Semitism in Europe was high on the agenda, Rabbi Pinchas Goldschmidt, president of the Conference of European Rabbis, sounded less optimistic. He said that while criticism of any government or government policy is legitimate, this measure singles out Israel among all the nations of the world.

“You don’t see a label on every gas station in Europe that this gasoline came from a country that beheads people or implements sharia law, or this item came from ISIS-controlled territory,” Rabbi Goldschmidt said. “So once Israel is singled out, we say that you now have a double standard that reeks of anti-Semitism.”

Oops! We could not locate your form.