9/11 Twenty Years On

Twenty years after 9/11, is America any safer?

"The weather couldn’t have been more beautiful,” recalls former White House press secretary Ari Fleischer of the promising start to that fateful second Tuesday in September 2001.

“It was a gorgeous, low-temperature, low-humidity, early September day. And we’d boarded the motorcade for a routine education event, at a Florida school. And as we left the motorcade, I got a page from an aide in Washington telling me that an airplane had hit the World Trade Center. And I just thought, There’s some type of accident, maybe it’s a small plane, it’s likely a small aircraft.

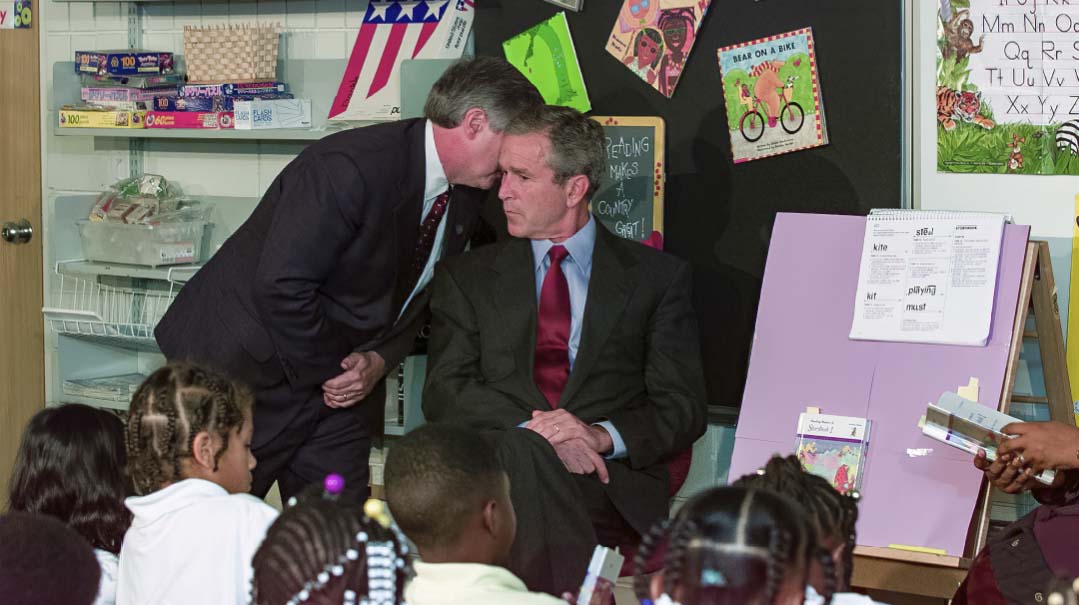

“And then, minutes later, I was at the school with the president as he was reading to the children. And I got a second page that the second aircraft had hit the second tower. And I knew immediately that it had to be terrorism. I knew immediately that something big was underway.”

The images have become emblematic: a shocked President George W. Bush being told that al-Qaeda terrorists have knifed two jetliners into an icon of American financial might. His frozen expression, eyes locked in laser focus as he processes the report being whispered in his ear, would symbolize the reaction every American had upon first seeing the incredible sight of Manhattan’s proud skyline being turned into a funeral pyre.

But for Ari Fleischer, part of the president’s inner circle as he reacted to the unfolding horror, a different scene stands out.

“The most chilling moment of the day for me was when, as I was standing next to the president, he said to the secretary of defense, ‘We are at war.’

“On a day when Americans are attacked and you hear the commander in chief say to the secretary of defense, ‘We’re at war,’ you recognize that the world is about to change. And whatever you thought was important before, now is not. That’s what I remember about September 11.”

Two decades on from those scenes of fire and fury, new media and new technologies are transmitting a new mise-en-scene: America’s shambolic retreat from Afghanistan, leaving that field to the very same turbaned extremists who provided a home base for the 9/11 attackers. The hasty US retreat has inevitably raised questions — both old and new — about that fateful Tuesday morning.

How did US intelligence not anticipate the attacks? What changes were made to the intelligence apparatus after 9/11, and did they work? Did all the new security measures — the Department of Homeland Security, the Patriot Act — make us safer? And who won the War on Terror?

You Just Do Your Job

Those with longer recall might retain an image of Ari Fleischer as the youthful 40-year-old press secretary to President George W. Bush on 9/11. The passage of time has wrought many changes but Fleischer’s memories of that day are still clear and sharp.

Can you describe what you felt when you heard the first report?

“Looking back, the most amazing thing to me about September 11 is how unemotional that was. Every day is serious at the White House. But on September 11, the only feeling was, it’s time to buckle down. Whatever happens, we have to face it, confront it, deal with it, be ready for anything. So you can’t get emotional.

President Bush was criticized at the time for sitting there in the classroom with the kids for a few moments before leaving. What do you think about that situation?

“He was criticized for it by a filmmaker who didn’t like George Bush to begin with, who unfairly dramatized the scene with a ticking countdown clock. But the simple truth is that it wouldn’t have changed the future. If George Bush had jumped out of his seat at that very moment, it wouldn’t have stopped the other two planes from hitting their targets. It was mindless criticism.”

What was the the rest of the day like?

“When we first boarded Air Force One, the information we were given was that there were six airplanes in the sky that still had not landed. While we were in the motorcade on the way to the airport, the plane hit the Pentagon. So there were three planes that hit their targets, and on Air Force One we were told that there were six more potential aircraft. So we thought there were nine missiles in the sky.

“The fourth plane [Flight 93] went down, and as they put it on Air Force One, in our first information about it, ‘It went down near Camp David.’ Now, where it went down, in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, was some 150 miles away from Camp David. But the first report was ‘near Camp David.’ And then we thought there were still five aircraft in the sky.

“So the whole day was a rush to collect information to understand exactly the nature of the attack. How much longer, how many more attacks could there be? How can we defend against them? President Bush authorized a shoot-down of a commercial airline, if necessary. He gave an order to go to DefCon Three, [a national security posture] which the United States hadn’t been on since 1973, during the Yom Kippur War.”

And because Air Force One flew at 45,000 feet, you couldn’t even see the news properly?

“The communications aboard Air Force One on September 11, 2001, were amazingly terrible. With limited TV service, we only got a signal when we flew over large, land-based antennae. The phones kept cutting out. It was just terrible communication that day.”

By the way, where did you end up landing?

“Well, we first went to Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana. Then we went to Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska, and we came home and landed at Andrews Air Force Base in the evening.

“Clearly, it meant that America was about to be at war, and like Israel, America now sadly knew what it was like to be attacked on our soil. Terrorists don’t play by the normal rules. They will do anything to kill on behalf of a radical ideology. And it meant that Americans would be at risk to protect us.

When was the first time you fully realized what happened?

“On Yom Kippur. It wasn’t the first time I understood what happened. I understood instantly. But I had a job to do. And in that situation, you just do your job. And it wasn’t until Yom Kippur... obviously, I didn’t work. I was talking to someone in New York City who describe to me what she saw that day from her window. And I’m a New Yorker. And that’s when I first cried. When I finally separated myself from my work. I suppose it’s part of Yom Kippur, the day of reflection. That was the moment for me personally.”

A Complete Failure

Dr. Howard Stoffer had a very different vantage on the events of that day. He didn’t have a seat on Air Force One, but his perspective sheds light on the causes for the catastrophe. Now an associate professor of national security at the University of New Haven, Stoffer served in the US Foreign Service from 1980 to 2005, and as deputy executive director at the Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate of the United Nations Security Council. On 9/11, he was at the US mission to the UN.

“I remember when the attacks occurred, we immediately vacated the US mission building across the street from the UN, because we didn’t know if the UN was going to be attacked,” Stoffer says. “The amazing thing was the next day, when the attacks were over. We went back to work, into the United Nations building, and found enemies of the United States —Cubans, Iranians, North Koreans. They were all coming up to us, saying, ‘We’re prepared to support any action, any resolution you want to take in the Security Council or in the General Assembly. We will support you. We’re sorry it happened.’ I was amazed to hear that.”

Stoffer points out that in the immediate aftermath, with this groundswell of support for the US, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1373 — “one of the most powerful resolutions ever adopted.” The measure bound UN member states in various counter-terrorism actions.

But while the Bush administration was gratified by this support, as the haze lifted from the tragedy, many began asking why the vaunted US intelligence apparatus had completely missed the signs of the impending attacks. Fleischer says that inside the White House, the president tried to maintain a united front. On the question of whether there was any fingerpointing among senior staff, Fleischer is adamant.

“No, we knew that day would come,” he says. “That was not the day for it. That was not George Bush’s approach. We always knew a full accounting would have to be made, but we were too busy to worry about it on that day.”

Stoffer, however, is frank about where the blame lay.

“It was a complete intelligence failure,” Stoffer declares. “We didn’t have the domestic [intelligence] services talking to the overseas services. There were memos sent to the president about people learning how to fly commercial aircraft. And that’s very strange, because usually people learning how to fly commercial aircraft are sent by the airlines, and not to certain schools. So that should have been an immediate warning that something was wrong. We should have picked that up.

“There was half a million dollars sent to the 22 hijackers, they’d been surveilling the airports. A lot of things happened that just made it very clear we did not have all of our early warning systems up and running and modernized.

“We certainly should have done something after the 1993 attack on the World Trade Center. I remember being in Moscow watching and thinking, my G-d, you know, they blew up the interior pillar of the building.

“It was an all-around failure, it really was. The other problem was that even the CIA was able to put together information, they didn’t share it with the FBI or the White House or other agencies of the US government.”

Much of this is borne out by Kenneth Gray, who served as an FBI special agent for 24 years conducting investigations on national security matters, counterterrorism, and computer intrusions. He attests that there were very clear signs of an impending attack during the summer of 2001. But the CIA miscalculated where the terrorists would strike, and the FBI lacked the foreign perspective to give context to what they were seeing.

“Based upon previous attacks against the US — the near simultaneous truck bombings of the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, the waterborne attack against the USS Cole — the consensus was that any attack by al-Qaeda would be against US assets abroad,” Gray tells Mishpacha. “Failures to share intelligence between the CIA and the FBI led to missed opportunities in detecting the 9/11 plot.”

This lack of interagency communication was one of the first problems addressed in the 9/11 Commission report, Gray says. Some responsiblities were shifted from the CIA to ensure better coordination.

“The overall direction of the intelligence community was a duty of the director of the CIA,” Gray explains. “The new position of director of national intelligence (DNI) was created as a position separate from the director of the CIA. The DNI is today responsible for coordinating efforts of the intelligence community.”

The FBI and CIA also now share intelligence through a joint program called the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), which is run by the DNI. And those aren’t the only changes, Gray says.

“The FBI has changed its priorities,” he says. “Prior to 9/11, the FBI was a criminal investigation agency that also had responsibilities in foreign counterintelligence investigations. Following the failure to stop the 9/11 terror attacks, the FBI has become a domestic intelligence service that also does federal criminal investigation.”

Did the War on Terror Succeed?

There were other reforms as well, of course. The Department of Homeland Security was created, and a maze of cumbersome new security requirements were imposed at the nation’s airports.

But most significantly, the Bush administration sought to take the fight to the attackers, declaring an international “war on terror.” The US embarked on costly, endless expeditions into Afghanistan and Iraq, in pursuit of al-Qaeda, and other threats. During those offensives, there were no major terrorist attacks on US soil. But with the US surrender of Kabul to the Taliban two weeks ago, can the war on terror be called a victory?

Dr. Boaz Atzili, associate professor at the American University’s School of International Service, thinks not.

“The war on terror did not achieve its goal of defeating terrorism, because it could not,” says Atzili, who focuses on international security and the Middle East. “Terrorism is a tactic used by certain groups to achieve their political goals. You can maybe defeat a specific terrorist group, but you can’t defeat terrorism.”

Atzili notes that while the US did succeed in minimizing the number and lethality of foreign terrorist attacks on American soil, terrorism as a force is still thriving.

“Globally, terror attacks did not come down, and probably increased,” he tells Mishpacha. “Just think about ISIS and its various extensions, for example. And the price in American troops’ blood has been high. To my mind, a much more modest approach, based more on policing and intelligence and less on military interventions, could have worked better.”

As to whether a large, 9/11-style attack could happen again, Atzili points out that it already has.

“These kinds of attacks by al-Qaeda and by ISIS continued after 9/11,” he says. “Spain experienced a large-scale attack against multiple trains and rail platforms on March 11, 2004. Britain experienced a large-scale attack on July 7, 2005, with four coordinated bombings against three London Underground trains and a double-decker bus.

“France has experienced several attacks. There were the coordinated attacks in Paris on November 13, 2015, with a bombing of a soccer stadium and mass shootings at restaurants and the Bataclan concert hall. And there was a ramming attack with a truck at a seafront celebration in Nice on July 14, 2016.”

Given this litany of attacks, can we say that the two-decade-long war on terror achieved its goals?

“The US invaded Afghanistan with the original purpose of ending the threat of Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda. The US invaded Iraq based upon false intelligence that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction and was supporting terror groups.

“The invasion of Afghanistan effectively crippled the activities of al-Qaeda. Osama bin Laden was forced into hiding and was unable to continue his activities. He was eventually located and killed. The Taliban, who had allowed Osama bin Laden to operate from its area of control in Afghanistan, was temporarily reduced. As a result of the war in Iraq, Saddam was defeated, and was eventually tracked down, tried, and executed by the Iraqi people.

“But an unintended consequence of this whole venture was the emergence of ISIS.”

With the US departure from Afghanistan, and a clear sense of Middle East war fatigue among the American public, how do you see the future of the war on terror? Could a new threat emerge? And who will stop it?

“I don’t have a crystal ball and I am not in the terror forecasting business. I can make some observations. In my opinion, the emerging threat of international terrorism has shifted from Afghanistan and Iraq to central Africa. This has been a problem for the EU. As African economic refugees settle in the EU countries, they bring members of the Africa-based terror groups with them. My guess is that this threat will continue to grow.

“The US military has been providing assistance to African nations through the US Africa Command [US AFRICOM]. However, the US has learned the lessons of Afghanistan and Iraq. The US will not be engaging in ‘nation building’ in any future conflict.

“China is a major power that is fully engaged in Africa, too. How that will effect the emerging threat and the efforts to combat these threats is unknown.”

A Grim Future

Dr. Howard Stoffer is also not sanguine about future US homeland security. He says the lack of political will for pursuing terrorists down Middle East rabbitholes will greatly complicate counter-terrorism efforts.

“It’s going to be much harder,” Stoffer admits. “We’re going to have to use what the community calls over-the-horizon capabilities, meaning that you’re going to have to use SIGINT, signals intelligence. You have to use communications intelligence and human intelligence and other methods to try to figure out what these different groups are up to, even though the territory they’re operating in is no longer friendly.”

And with none of its own troops’ boots on the ground, the US will have to find partners in the effort.

“We’re going to have to work with other countries that have the ability to penetrate some of these areas and be able to figure out what’s happening,” Stoffer says. “It will include other allies of the United States, including Israel, the Europeans, and the agencies that we work with to be able to monitor what’s going on.

“It’s going to be a threat to everybody, not just to the United States. I think we’ll still be able to defend ourselves. I think other countries will work closely with the United States.”

Asked to sum up the war on terror, Stoffer is somewhat philosophical.

“Once it was clear that al-Qaeda was destroyed in Afghanistan, there was absolutely no reason to stay very long,” he says. “On the upside, there have been no major attacks in the United States since 9/11, aside from a few domestic terror attacks.”

As to whether 9/11 could happen again, Stoffer is uncertain. “I don’t know. I’d like to believe that we have a much more sophisticated operational capability, from technological improvements and from other things that we’ve learned over the last 20 years.”

Ari Fleischer, the White House press secretary who is now a media and political consultant, gives his perspective 20 years later on what went right and what went wrong in the war on terror. There are some positives to point to.

“What went right is that we have a bipartisan template of how to fight terror,” he says. “Started by George Bush, continued by Barack Obama and Donald Trump and Joe Biden. And it involves information sharing between the FBI and CIA, the use of drones to gather intelligence and launch offensive strikes when necessary, and a much more beefed up intelligence capability globally.

“And we are just generally tougher on those who try to harm us. We stopped trying to fight this through the courts. And we realize we have to fight it with more aggressive elements that we have at our disposal. And that’s been bipartisan, and that’s very helpful.”

Fleischer views the retreat from Afghanistan as a setback to all those efforts, however. “I do fear that what will happen now, with Afghanistan again becoming the breeding ground for terrorists. I would hope we learned some lessons from Iraq, in that regard.”

He contends that future counter-terrorism efforts should take into account the sacrifices made by the American public and the armed services over the last 20 years. The political will for new military adventures is nonexistent. Even the minimal commitment the US was making in Afghanistan is too much.

“What I’ve come to realize is that American presidents have gotten tired of making the case,” Fleischer says. “It’s so much easier to say withdraw, come home, which is very much a part of American history, than it is to move the country with the argument that 2,500 troops will allow us to stop the terrorists from regrouping while supporting the Afghans so they can do their job. And that this is not war. America is not in a forever war. We are in the forever mission to stop terrorism. And that’s not a full-blown war. People exaggerate it to make it look like it is a full war.”

Unfortunately, Fleischer says, the US will never be able to let down its guard. “I’m fearful for the future, of course, because terrorists know how to regroup.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 877)

Oops! We could not locate your form.