50 and Counting

After five decades of innovation and inspiration, Mordechai Ben David is still at the mic

Photos: Kobi Katz, Tzvi Miller

He was the shy kid in the family, the one most unlikely to get up and sing in public. But five decades and dozens of albums after a young chassidish fellow named Mordechai Werdyger swallowed his fear in an opening act at Brooklyn College, the “King of Jewish Music” is still belting out winning compositions, relevant as ever, while staying true to his ideals — perhaps the real secret to his success. MBD might have celebrated a jubilee, but he’s not yet ready to hang up his mic

Mordechai, who initially knew nothing about this impromptu performance, says he was quivering that whole Shabbos, not stepping out of his bungalow, dreading the moment Shabbos would be over.

“But my friends insisted,” he remembers. “They came over and literally dragged me to the auditorium, depositing me on the stage. I was shaking, but then I started singing, and somehow my fears melted away.”

He sang a few of his father’s songs and some of the songs from his own upcoming first album. It wasn’t exactly a concert to remember, but for Mordechai Ben David, it ignited a trajectory he could never have fathomed in his wildest dreams.

“My first real performance was at Brooklyn College in 1972, where I sang as the opening act for the Ohr Chodosh group before an audience of about 2,500 people — and I got a whopping $50 for that night,” the “King of Jewish Music” says of his debut, as he celebrates 50 years in the industry. “Reb Moishe Kahan a”h, a record producer, apparently liked my singing and asked me to do the opening for an upcoming concert with Yigal Calek and the London School of Jewish Song, who were touring New York then. By then my fee had gone up to $250.”

Forty-six solo albums and over 40 collaborative albums later, Mordechai Ben David, celebrating his personal yovel in the business, considers the unlikely fact that he’s one of the greatest influences on the current chassidic music genre. Unlikely, because although he comes from a highly musical family — back in the ‘50s and ‘60s, his father, chazzan David Werdyger a”h, released dozens of recordings from various chassidic groups and was the first one to record the niggunim of Reb Yankel Talmud — of all the musical prodigies that the Werdyger family produced, he was considered the shyest and most introverted of them all.

“I was petrified to perform in public,” he relates. The odds that he, of all his siblings, would become a groundbreaking musical icon, were close to nil.

“I’m the only one of us four brothers who never wanted to sing,” he shares. “I was very shy. My brothers davened before the amud with no problem and sang wherever they were asked. To this day, I cringe when I have to go up to be chazzan.”

But the plans written Above were different. Over the years, his dozens of albums and hundreds of popular songs generated a revolution in the world of music, and you’d be hard-pressed to find a frum home anywhere in the world where his songs haven’t been played.

And although music seemed an unlikely future, it pursued him relentlessly.

“I have a brother-in-law named Ari Klein,” he says, going back to the starting point. “Fifty years ago, he was a chazzan, composer, and wedding singer. Once, at the wedding of a relative, he decided to drag me up to sing with him, and after that we started composing songs together. One day, I was sitting at the piano in my father’s house playing a new tune I had just composed. My father came in and asked, ‘What’s that song? I like it.’ I told him it was something I wrote. He asked me to play some of my other compositions and then practically begged me to go to the studio and record them. But I was totally not ready to sing in a studio.”

Still, he was ultimately convinced, and recorded his very first album, which he refers to as “the Minus-One album.” It was titled Mordechai Ben David Werdyger Sings Original Chassidic Niggunim, and most of those original niggunim never really took off (except for two songs — “Yosis,” which MBD revamped in a later album, and “Hashiveinu,” which, with a revised beginning, became a popular dance and camp song in the 1970s).

Why “Minus-One?”

“Listen to it, and you’ll understand,” he says. “Or maybe, don’t bother. Those first songs and their musical accompaniment weren’t fully crystallized. The following year, in 1974, the Hineni album was released, and I really consider that my ‘first’ album. The music was arranged by Yisroel Lamm and written for a full orchestra, including strings and brass. It was a fresh sound in Jewish music, a major upgrade.”

Hineni debuted some favorites of the ’70s, including “Ki Lo Yitosh,” “Shema Yisrael,” and the decade’s most popular version of “Od Yishama.” The title track might not have been as catchy as the others, but for MBD, it was one of his first forays into writing about what was really important to him — a trademark he’d continue to develop.

“This song was written at the request of Rebbetzin Esther Jungreis a”h, as she embarked on her mission to spread the light of Hashem and ignite the spark of light in every Yiddishe neshamah with the founding of the ‘Hineni’ organization,” he shares. “She traveled the world with the passionate messages she so eloquently delivered, bringing so many lost souls back to their roots.”

Nevertheless, that first “Minus-One” album did bring MBD his early invitations to perform.

And how did he come up with the stage name? “One of my friends suggested that I hitch a ride with my father’s name,” MBD recalls. “My father was very well-known, and it would be easier for me to break into the music world as his son. I considered this friend a shrewd businessman, so I took his advice.”

While his fans and friends are counting off the jubilee, for 71-year-old MBD, it’s pretty much the same: the deep voice that’s only grown richer over the years, the ear for a really exceptional composition, and the ability to take a niggun, own it, and move it forward.

Yet each of the past five decades tells its own story.

“You can’t take anything from anyone if it’s not meant to be.” Mordechai ben David reflects on fifty years at the mic with Mishpacha’s Aryeh Ehrlich

The 1970s: Finding His Voice

A

fter MBD released his first “real” album, Hineni, Reb David Werdyger recorded an album with a young arranger by the name of Moshe Mordechai (Mona) Rosenblum. “He was a young bochur at the time,” MBD recalls. “The album was called Niggunei Werdyger. I liked the arrangements very much, and I myself now had enough material for a new album, so I flew to Israel to meet with Mona. After discussing the project, Mona went searching for musicians who were proficient in reading notes and had the talent to execute this project. After an intense search he finally found a suitable group, and we then spent ten days holed up in his parents’ home. The result was the Neshamah album.”

If Hineni had set a new standard in chassidic music, Neshamah was something else entirely. The new arrangements, the style of the compositions, and the sheer “Israeli-ness” of it — some songs sung in Israeli Hebrew with a distinct Middle-Eastern rhythm — gave Mordechai Ben David exposure to a wider array of Jewish music fans.

That might have been his career trajectory, had he not experienced a transformation in his personal life. Soon after Neshamah was released, he met and became very close to the Ribnitzer Rebbe zy”a, the tzaddik and baal mofeis from Moldova who left the Soviet Union in 1970 and journeyed to New York after a several-years’ stop in Jerusalem.

Mordechai says the Rebbe “effected a revolution in my life and gave a new direction to my music.” The result was the I’d Rather Pray and Sing album — the title track a stirring song of longing and teshuvah, the lyrics written by the much younger Ribnitzer Rebbetzin, Freida Milka Abramowitz a”h. The album is an MBD classic, including his vintage “Odcha Hashem,” “Harachaman Hu Yishlach Lanu,” “Eizehu Mekoman (Yiddish),” and the iconic MBD “Kah Ribbon,” a niggun that acquired an integral place at the Shabbos seudos in Jewish homes around the world. One of Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv’s grandchildren told MBD that even on the last Shabbos of his grandfather’s life, the gadol, known for his musical ear and proficiency in niggun, sang this “Kah Ribbon” at his seudah.

Mordechai topped off the decade with his Vechol Ma’aminim — Songs of the Yamim Noraim album, produced by then-young Suki and Ding.

David Nachman Golding (aka Ding) recalls, “It was 1978, and Suki and I were in Yeshivas Itri. We had an agreement that we wouldn’t talk business during the yeshivah zeman, although we had already put out one album, and my partner Suki was an accomplished musician who’d played for many performers, but it was the last Motzaei Shabbos before we’d be heading home for Pesach, the beis medrash was empty, and Suki turned to me and said, ‘Did you hear that niggun that they sang at Shalosh Seudos? What a great song!’ And then he started to sing what is now known as ‘V’chol Ma’aminim.’

“After seder was over, we heard that MBD was doing a Motzaei Shabbos concert in Binyanei Ha’umah, so we hopped into a cab and figured we’d try a shot at the backstage door. We expected a guard to answer and throw us out, but Mordechai Ben David himself opened the door, telling us that he was just waiting for his turn to go onstage. He was happy to see us — Suki had accompanied him before — and as we crowded in, Suki found a piano and asked Mordechai if he’d like to hear a special niggun. He began playing the tune he’d heard in yeshivah just a few hours earlier — and MBD was blown away by the melody. So I took a chance and said, ‘I’ve always dreamed of making an album that features the most popular Yamim Noraim niggunim. Would you be interested in making that type of album with us?’

“MBD was in, and that’s how we created the vintage album we all know today as V’chol Ma’aminim. And then, right after the album came out, we learned that that amazing niggun we’d put to ‘V’chol Ma’aminim’ had actually been written by Shlomo Carlebach as ‘Tov L’hodos L’Hashem.’ ”

Traditional Shabbos zemiros, rousing wedding songs, soulful Yiddish ballads, even political statements wrapped in melody – over the decades, MBD has sung them all

The 1980s: Take a Stand

T

his was a pivotal decade for Jewish music, pushing the industry into a more prolific and sophisticated place.

Chassidic music developed, and MBD was joined by another significant artist named Avraham Fried. During these years, they had their own trajectories but also appeared together on stages around the world and became — each in his own right — probably the two most important names in contemporary chassidic music. And even with the passing decades, both have remained front and center stage.

“There’s no jealousy or competition between us,” Mordechai says of their longtime relationship. “In fact, I was involved in helping him with his first album. Each one of us has his own unique style. You can’t take anything from anyone if it’s not meant to be — everything in life is destined from Above, and just like every bullet has an address, so does every song. No one can touch what’s destined for someone else.”

During those years, MBD released a staggering 12 albums, several of them making unabashed statements about the challenges facing Eretz Yisrael and the Jewish world. There was Just One Shabbos (1982) — a tribute to the indefatigable Meir Schuster a”h, who spent his days tapping young people on the shoulder at the Kosel to offer them a Shabbos experience; Hold On (1984) and Let My People Go (1985) — a message of hope for Natan Sharansky, incarcerated in the Soviet gulag, and other Prisoners of Zion; and Jerusalem — Not for Sale (1986) — Mordechai’s personal protest against the grand Mormon center that was to be built on the foot of Har Hazeisim opposite the Temple Mount, and then-Mayor Teddy Kollek, who gave them a large chunk of prime property.

References to previous enemies who had over the centuries failed in their bids to wage war on the holy city, and raw outrage at the perceived Mormon intentions of proselytizing, made this a passionate song of protest. (In the end, the campus was built and remains a prominent fixture on Jerusalem’s eastern skyline, after the Mormon Church pledged that there would be no proselytizing or missionary work coming out of the campus.)

“I firmly believed that it was the right thing to record that song, and that’s what I did,” MBD says, with close to three decades of hindsight. “The Gerrer Rebbe, the Lev Simchah, was deeply pained at the idea that the Mormons were building their center on this holy soil, and he fought bitterly to prevent it. On Chol Hamoed Pesach of 1986, the Rebbe planned to organize a huge demonstration across from the Temple Mount, and he asked me to perform during that demonstration. I composed the song ‘Jerusalem Is Not for Sale,’ and that demonstration is forever etched in my memory as one of the most moving moments in my life. I was standing across from the Har Habayis, and I have no words to describe what it felt like — totally connected to the battle over the sanctity of Yerushalayim.”

The 1990s: Days of Mashiach

S

ometimes it seemed as if Mordechai was competing with himself. Time and again, he set himself a very high bar, a fact he doesn’t deny.

“I know that nothing of this is me,” he says. “It’s all siyata d’Shmaya. HaKadosh Baruch Hu put me in this place. I merited many gifts from HaKadosh Baruch Hu. One of those big gifts was getting to know my rebbe, the Ribnitzer zy”a. People from across the Jewish spectrum, and even beyond, flocked to get his brachos, and they saw open miracles as a result. He passed away on 25 Tishrei, 1995, and on his yahrtzeit, more than 50,000 Yidden came to pour their hearts out and ask for yeshuos in the merit of the tzaddik.

“I merited to be meshamesh him for five years. For one year, I was literally a ben bayis, and during the other four years, I was a meshamesh bakodesh, to the extent that I slept in a bed next to his. There was a time when my wife came to the Rebbe and began to cry that she couldn’t do it — she had little children at home and I was always with the Rebbe. He said to her, ‘Please leave him here, and I promise that you will never lack anything in your life.’ The Rebbe’s promise has been and continues to be fulfilled — it accompanies me everywhere in life. A person does nothing on his own.”

Mordechai says he also merited to have a connection to the Lubavitcher Rebbe zy”a. “He always encouraged me and gave me chizuk,” MBD relates. “He would tell me, ‘Kabeid es Hashem migroncha — Honor Hashem with your voice.’ Once, I was there on Motzaei Yom Tov when the Rebbe distributed kos shel brachah. He gave me a bottle of vodka and said, ‘The Gemara says that a Yid who gladdens other Yidden has a share in Olam Haba.’ Once on Erev Yom Kippur I came for the distribution of lekach, but I was late, so I came back on Hoshana Rabbah. In the succah, the Rebbe blessed me that I should merit to gladden Yidden until the arrival of Mashiach, and then we will truly rejoice. Those brachos from tzaddikim were a long time ago, but they’re still keeping me going.”

He admits that after the album Just One Shabbos in the early ‘80s, he asked himself, “Where do I go from here?” He also felt that he had reached a certain ceiling that was hard to break through time and again. “But HaKadosh Baruch Hu gives more and more and doesn’t stop, and didn’t let me stop either.”

Were there times when he said, “That’s it, I’m hanging up the microphone”?

“I tried a few times,” Mordechai admits, “but Hashem didn’t let me. People drive me crazy all the time asking when the next album is coming out. The truth is that today, I don’t think that financially it’s worthwhile to produce an album. There is a tremendous financial investment and endless hours of work, but the feedback from people who get chizuk from it motivates us to go on. Yeshivah bochurim who have experienced crises, people experiencing all kinds of struggles, are always expressing their thanks for the chizuk they get from the music — and not only mine. So I guess this is still my tafkid, as long as I can still do it and still have the kochos.”

The opening volley for the ‘90s was the Double Album (1990), produced by Shea Mendlowitz, the initiator and producer of the famed HASC concerts, featuring over a dozen new songs with exciting new arrangements by Yisroel Lamm. After that came Solid MBD (1990), Live in Yerushalayim (1991), Moshiach Moshiach Moshiach (1992), and Tomid B’Simcha (1994).

He calls that time the “Days of Mashiach” — because that was the theme running through the compositions of those years.

“Many years passed until we reached ‘Yemos haMashiach’ — the days when we recorded ‘Moshiach,’ ” he shares. “We already had an entire album ready with most of the songs composed by Yossi Green. But I felt I was missing one song to really shoot it up a notch. I called Mona, and I said, ‘Listen, I want to sit with you, but on condition that you unplug all the phones and close the door of the studio.’ He agreed, and then Hashem gave us the gift of the song ‘Moshiach,’ which we composed together, to be followed by ‘Shema Beni’ and ‘Samcheinu Hashem Elokeinu,’ but ‘Moshiach’ was the icing on the cake that put the album over the top.” The title track also caught on with secular Israeli music lovers, helping make Moshiach his top-selling album of all time.

While waiting for the true and eternal “Days of Mashiach,” both MBD and Mona Rosenblum meanwhile augmented the spiritual dimension of their lives. “During the time we were working on the Moshiach album, we began to learn some Torah together each day before work,” MBD relates. “Baruch Hashem not only was the album successful, but all that Torah learning changed Mona’s life. Although he grew up in a Gerrer shtibel in Ramat Gan, it was considered a ‘shtibel of clean-shaven chassidim’ — mostly Holocaust survivors. His father a”h, who had lost a wife and children during the war, and his mother a”h, who had lost a husband and children, got married after the war. His mother was an exceptional tzadeikes, busy with chesed her entire life. I can honestly say that I admire, respect, and even envy him that he sits and learns almost all day. He lives Torah, gives shiurim, and in a way, he’s my teacher, too, by example.”

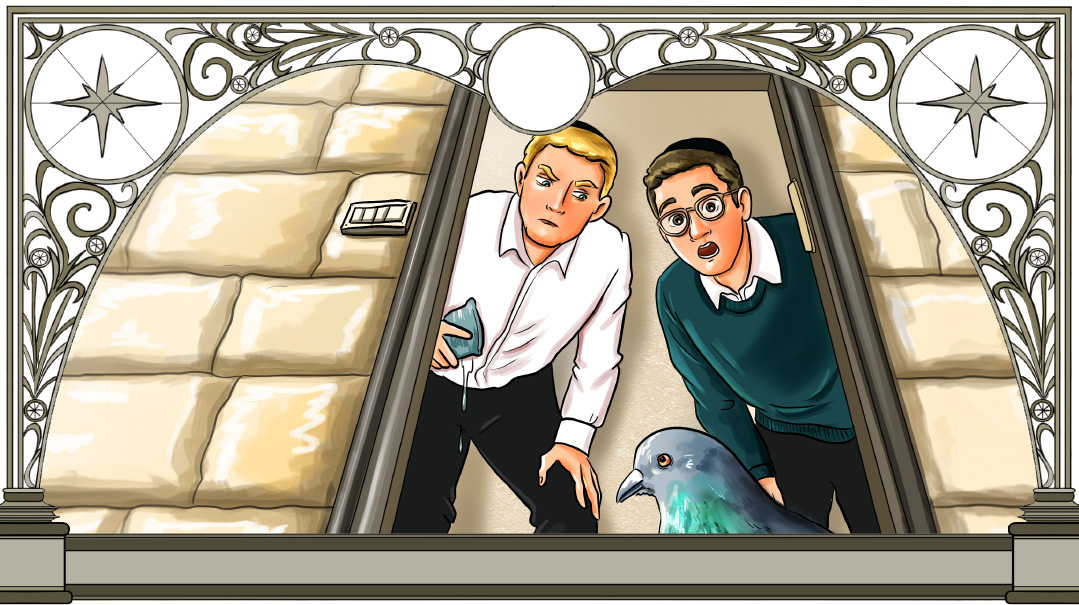

Of all of Chazzan David Werdyger’s sons, Mordechai (right) was the least likely to perform in public. But he pushed past the stage-fright and connected with audiences around the world

2000-2010: Where’s the Heart?

T

his decade began with Ma’aminim Bnei Ma’aminim, launching more albums in MBD’s familiar style. With energetic hits like “Ma’aminim,” together with deeply emotional and poignant songs such as “Torah Hakedoshah,” the public kept asking for more — and he kept delivering, with such titles as Kumzits (2003), Nachamu Ami (2004), Efshar Letaken (2006), Yiddish Collection (2007), Kulam Ahuvim (2009), Platinum Collection (2009), and a few popular singles (think “Anovim Anovim”) in the mix as well.

These years gave rise to a new generation of musicians and artists, who began to flood the Jewish playlist, saturating the market. On the one hand, so many new titles — some great, others barely average — diminished the status of the old classics, yet here was a young generation that had new, fresh talent. If you ask MBD, he’ll tell you that he doesn’t listen much to today’s music and knows even less about the young generation.

“People ask me what I say about today’s music, and I say that I don’t know today’s music. I don’t listen to any music at all, so I can’t really give an honest opinion. What I can say is that success doesn’t come from preening and looking cool. That’s all an illusion. Real success isn’t about making yourself into something you think your audience expects. You have to just become closer to HaKadosh Baruch Hu. Music, just like everything else in life, is strictly a gift from above.

“I did collaborate with Motty Steinmetz though, and I’m proud of that. He’s a Yid with deep emotion and lots of neshamah, and that is the main thing in music. And on Kulam Ahuvim I recorded a song with Aharon Razel— an exceptional person with so much heart and emotion and a true ben Torah.

“There are people who have fantastic voices, but if it doesn’t come from the heart, it can’t reach the hearts of the listeners. Rachmana liba ba’i — Hashem wants our hearts, and if there is no heart, then what’s the tachlis?”

That attitude has become part of MBD’s “real” life as well, not just behind the mic. And, he says, it starts in shul.

“We have a minyan that was started in my house in Seagate when my father a”h was too weak to go to shul. After Hurricane Sandy in 2012, which caused tremendous damage to our home, we renovated and built a shul in the basement. We established the MBD minyan — which is actually an acronym for ‘Minyan Bli Dibbur’ — anyone is welcome to come and daven, but no talking allowed.”

If you come to shul to talk, he says, where do you go to daven? “The shul is Hashem’s ‘house’ — where we have an opportunity to speak to Him directly, to thank Him for all the good in life, and to pray for ourselves and our loved ones. If you’d have an audience with a mighty king who had the ability to fulfill all your wishes, would anyone in their right mind pull out their cell phone?”

2010-The Present: Looking Ahead

W

hile Mordechai has 50 years of great music under his belt, and most people his age are happy to retire, he still feels he has much left to accomplish.

He’s even still collaborating with Mona. “A year ago, we sat down and recorded a lot of material, and I hope the next album will be based on that material,” he says. “I have enough recorded material for three albums. In the coming year, b’ezras Hashem, there will be a new album. There’s lots of good material, both from Eli Klein and Yitzy Berry, who produced and wrote most of the songs on the more recent Tzeakah album.

“The truth is,” he reveals, “that I began to work on this upcoming project before the recent Hashpuos album with Chezky Weiss’s compositions, but Chezky came in the middle of my recordings and my son Yeedle pushed me to postpone the project and work with Chezky first. Baruch Hashem it came out very special. Chezky Weiss is a top composer, and he has siyata d’Shmaya — the album came out amazing. My son Reb Yeedle was the real producer there. He invested a lot of work and effort into it — all of Yeedle’s albums are special.”

Like everything else in the world about which it is said that the end has already been predestined from the beginning, Reb Mordechai never forgets his challenges of his youth.

“I have a brother, Reb Yisrael Aryeh, who is three years older than me,” he says. “There was no Gerrer yeshivah gedolah in America at the time, so everyone went to Eretz Yisrael. The younger ones went to Chiddushei Harim, and the older boys went to Sfas Emes. When I was 12 years old, I came with my parents to visit Yisrael Aryeh, and he said to me, ‘Go into the Rebbe [the Beis Yisrael] and tell him that you’re worried about going back to America because of the ruchniyus situation there.’

“The Beis Yisrael said to my father: ‘Leave him here.’ Now, Chiddushei Harim was for bochurim who were older than me, but there was a yeshivah in Bnei Brak called Yeshivah D’Chassidei Gur, which later became Imrei Emes. There was a mechinah for yeshivah ketanah there. Remember, I was just 12, and the only American boy there. I didn’t speak a word of Hebrew, and there were just a few Yerushalmi boys who spoke Yiddish. It was very hard for me, and so was the poverty. There was no food. We’re talking about 1963, when there were cars, but there were also still horses and buggies in the streets of this poor, new country. On Rabi Akiva Street, there were porters with horses and carriages selling blocks of ice, because many people didn’t have refrigerators. After two years, I went to Jerusalem, where my brother was learning. I didn’t get a bed for a year. In the winter I slept on the floor on a blanket. But I survived, baruch Hashem. It wasn’t an easy time for me, but the Beis Yisrael drew me close.”

When he was 17, he left the yeshivah. “Half a year later, I got engaged. My son Yeedle was born when I was 19. He’s almost my age, you could say… he even has grandchildren. It’s all gifts from Above. We have to thank Hashem for every minute.”

Even at the height of his career, it hasn’t always been smooth sailing. Like when his home studio was destroyed by Hurricane Sandy. People then were speculating that that would push him to his long-awaited aliyah. And he even owns an apartment in one of the new developments around Rechov Shamgar in Jerusalem. Is it actually going to happen any time soon?

“In Breslov they call it meniot, all kinds of things that try to prevent you from getting where you want to go. Baruch Hashem we have a home in Jerusalem. But it’s easier for my wife to live here for now. The grandchildren and great-grandchildren live here. But I constantly daven that we will merit to live in Yerushalayim permanently. People ask me where business is better, but frankly, it makes no difference. HaKadosh Baruch Hu gives you wherever you are. He gave Rabi Shimon bar Yochai carobs even in the cave…”

HIS FATHER’S SON

I first heard about MBD when his father, Reb Dovid Werdyger, sang at a concert in Haifa. He was a very special person. We were good friends. He was a precious Yid with an amazing voice, and I still have dozens of his recordings. At the concert, there was a bochur on stage whom he introduced as his son. They sang together — Mordechai was very young then, and that’s when I first saw him. After that, we met many times and had many working meetings as well. He took “Unesaneh Tokef,” “Mizmor Shir Leyom HaShabbos,” and the popular niggun he sings to Keil Adon (on Just One Shabbos) from me.

Mordechai is a tremendous artist, but I’ll admit that I personally love his older chassidic niggunim. Still, he’s a giant in whatever he does.

—Veteran composer Reb Chaim Banet

ALL HIS HEART

I’ve known Mordechai since he was a teenager when we had the Rabbi’s Sons group. But I would say the greatest moment we had together was at one of the HASC concerts — I was there with my guitar and a harmonica in my mouth, and MBD was at my side, belting out a fast dance song. On the other hand, I was once with him on Pesach, and people remained for hours — they couldn’t bring themselves to leave. He sang with such dveikus, with all his heart.

If I had to choose a favorite song, I’d say “Racheim Bechasdecha,” a song I composed together with Abie Rotenberg that first appeared on our Kol Salonika album in 1977. Mordechai gave it his own style on MBD and Friends and it became a Shabbos standard.

—Rabbi Baruch Chait

THEY’RE ALL THE BEST

He’d composed the song “Samcheim” and played it for me, and I added another part. Then we sort of forgot about it. Before his son’s wedding, he wanted to release a cassette, so I composed a song for him, but we had to put something else on the other side of the cassette. Suddenly we remembered about “Samcheim,” so we put that on. When I wrote the arrangements for it, I included an introduction that today everyone remembers — and it was all really an afterthought.

We’ve worked together for so many years that it’s hard to pinpoint one special song or album, but the truth is that I did two full albums for him, Hold On and Jerusalem — Not for Sale. Baruch Hashem, I’ve been privileged to do a lot of beautiful things — both composing and arranging — together with him over the years. Ultimately, each album has hits, all of which are good — and therefore, there isn’t a best, because they are all the best.

—Composer/arranger Moshe Laufer

GONE WITHOUT A TRACE

I was about 12 years old in 1967 when Mordechai came to the Arugas Habosem camp in order to assess my singing. His father was in the middle of producing the Skulener Niggunim album, and they needed a child’s voice. I remember that Mordechai came with his good friend, Chazzan Ari Klein, who later became his brother-in-law. He gave me an audition and wanted me to join in the recording, but in the end, my father didn’t let me. Mordechai did sing on that tape, and I remember that when I listened to the Skulener song “Shiru Lo Zamru Lo,” I couldn’t believe that amazing voice.

Today we’re neighbors and have collaborated on dozens, maybe hundreds of songs, but there was one special encounter we had together that I’ll never forget. It was 28 years ago, at the time of the First Intifada, and we were together in Chevron, at the Mearas Hamachpeilah. We had arranged an armored vehicle. The guards stayed outside, and we went in to daven. The hall of the kever of Yitzchak Avinu is quite large, and we were surprised that there wasn’t a single person there. Suddenly, we saw a man with an open sefer, and he smiled at us invitingly.

Mordechai and I looked at each other — where did this man suddenly come from, and why was he smiling at us? There was something both frightening and calming about his appearance. Suddenly, he motioned with is finger that I should come closer, and with another finger, he pointed to the text in the sefer. I saw that he was holding a Maseches Berachos. It was opened to daf 7a, and his finger pointed to the story of Tanya Amar Rabi Yishmael ben Elisha — the words I’d set to a niggun a few years before. I motioned to Mordechai to come close, quickly, and then the old man began to speak. “Tell me, this Gemara is very important to you, right?” I could barely nod. “You agree that it’s time that we should have a Beis Hamikdash and a Kohein Gadol? Hashem should help us all that the geulah sheleimah should begin, because we are waiting.”

Mordechai had a camera and I signaled to him with my eyes that he should take a picture. When we emerged, we called the security guards to come to the place where we’d been, but when we entered again, we found the closed Gemara on the bimah, but not a trace of anyone. Later, Mordechai and I went to develop the photos — and there was no one there! The man had simply disappeared.

Since then, whenever I ask Mordechai if he remembers the story or if it was my imagination, he always says, “Yossi, there’s no doubt that it happened. It’s amazing, and there are no explanations for it.”

—Composer Yossi Green

TAKE NO CHANCES

The first time we met was before he released the album We Are One in 1999. I was still a bochur, before my musical career, and I’d written a song for Michoel Schnitzler. He lived in Seagate then, and told Mordechai that he had a new song in Yiddish that some young guy wrote for him. Mordechai got excited, and said he was actually looking for someone to write lyrics in Yiddish for a tune. Michoel gave me the information, and I called Mordche at home. He told me he’d send me a playback of the niggun and that I should write the words.

I didn’t want to give up on the opportunity and figured that if I’d do only a demo like he asked for, it wouldn’t sound good enough. I didn’t want to take the risk. Today, I have more self-confidence, but then, that’s what I thought. I told him I wanted to come to his house in Seagate, and I’d write the words on the spot.

He told me there is no such thing, and no one writes lyrics like that. I told him I’d explain it to him, and I’d sing it to him there. He saw that I was very interested, and said, “Nu nu.” I took a bus to Boro Park and a taxi to Seagate. I wrote the words for him on the spot, and he said, “Amazing!” That became the song “Baruch Hashem.” We became friends after that, and since then, he’s taken a song from me on every one of his albums.

—Lipa Schmeltzer

Rachel Ginsberg contributed to this report.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 937)

Oops! We could not locate your form.