30 Days Before

| March 7, 2018Forty years after the murder of Yosef Dov Weissman Hy”d, family and friends are still amazed that he wrote a will after envisioning his own death

"S

ometimes a person is privileged to get a distinct feeling that he is going to die, so that he can do teshuvah out of fear of Hashem.… I know that in the near future I will be standing before the Heavenly Court.” Forty years after the murder of Yosef Dov Weissman Hy”d by a terrorist on a bus with a suicide belt, family and friends are still amazed that he wrote a will after envisioning his own death

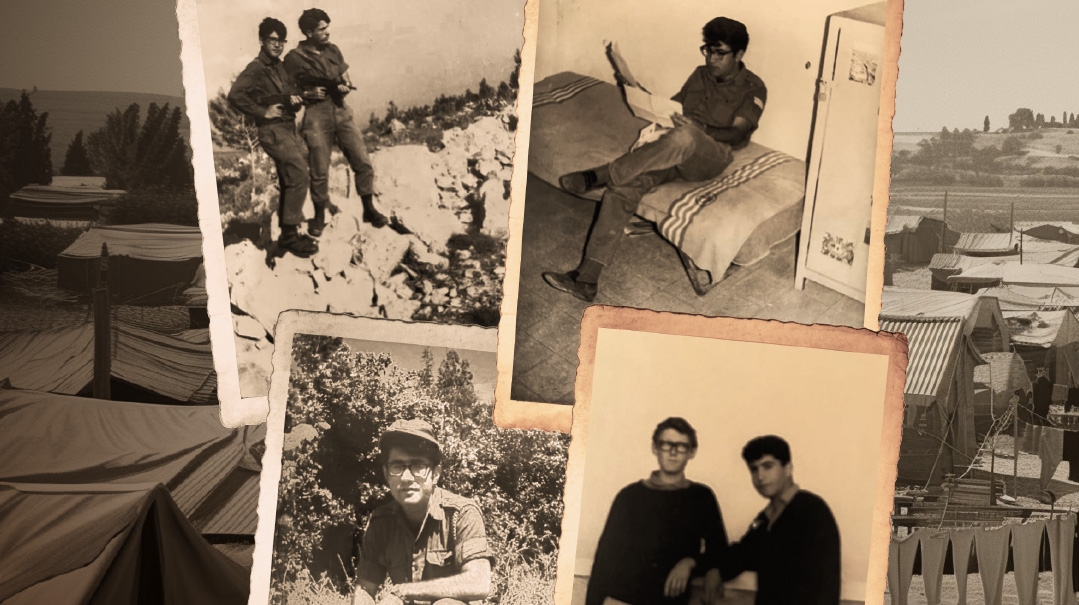

Back in February of 1978, Tzvi Laufer was a newly married man, fresh out of Yeshivas Chevron and living in his own homey, comfortable apartment in Jerusalem’s Sanhedria neighborhood. He was happy to host his longtime friend who was still in yeshivah, a 23-year-old bochur named Yosef Dov Weissman, considered the illui of the yeshivah as well as a nonstop chesed machine — the two had shared many milestones as they went through life together, and now Laufer wanted to include his old friend in his new good fortune.

A Kitzur Shulchan Aruch resting on the table caught Weissman’s attention, and he began to leaf through it as they spoke. As he flipped pages, a paper filled with small yet neat writing fell out. Weissman scanned the paper for a moment and then gasped. “What is this?” he cried to Laufer, who waved it off. “Oh, that. It’s the nusach of Vidui,” Laufer replied casually. “I need it because I’ve started visiting hospitals — I go to terminal patients who are on their deathbeds.”

Laufer didn’t attribute much importance to the paper and the Vidui and tried to change the subject. But Weissman had no intention of moving on. He took the paper again, and began reading the nusach with great interest. Silence hung in the air for several minutes, and then Weissman seemed agitated, in a sudden hurry to leave. He thanked his host, and was soon out the door. From there he went to the nearby bus stop and got on the number 35 bus, which began its route in Ramot and would take him in the direction of Givat Mordechai and his yeshivah.

But Yosef Dov couldn’t take the noise generated by a group of raucous street kids, and so he moved through the packed bus all the way to the back — never fathoming how he’d just sealed his fate. As the bus turned onto Tzefaniah Street, there was a deafening explosion: An Arab terrorist sitting in the back row with an explosives belt strapped to his waist blew himself up — injuring 45 and killing two. One was a 42-year-old father of seven named Kasriel Blumenfeld; the other was Yosef Dov Weissman. They would be among the first korbanos of a 40-year- long string of suicide bombers that would take the lives of thousands of Jews in Eretz Yisrael.

“It was 40 years ago, on 8 Adar 5738,” Laufer relates to Mishpacha. “One of the first suicide bombings. I was the last one to see Yosef Dov, but at the beginning I was so shocked that I didn’t realize the significance of the scene that had unfolded in my house just half an hour before. Only two days later, as I was on my way to Tel Aviv to pay a shivah call to his broken parents, I suddenly realized what happened: He said Vidui in my house! Imagine, his mazel sensed what was happening half an hour before he was killed, and Hashem granted him the privilege to recite Vidui.”

The wonder and shock still lace Laufer’s tone. Even today, 40 years later, he becomes agitated when reliving those memories. “It constantly inspires me to do teshuvah,” he explains, “but that’s only part of the story.…”

The rest would be filled in by Rabbi Yehudah Breitkopf, rav of the Chasdei Naftali shul in Har Nof, whose room was across from Yosef Dov’s in the Chevron dorm.

“He was a bit of an older bochur, but he was also close to the younger bochurim. Although he wasn’t talkative, there was something captivating about him. He had a heart of gold and sterling middos — he would reach out to every single person in the yeshivah. But then something strange happened. About a month before he was killed, he started saying all kinds of strange and ominous things that were difficult for us to hear. He told me a few times, ‘I feel like I’m going to be leaving the world,’ or ‘I need to write a will.’ He even brought to his room all the seforim from the library that discussed wills, and studied them at length. I saw that he was really overcome with thoughts about passing on, but I didn’t imagine, didn’t dare fathom, that it was something genuinely serious, some sort of premonition. I just thought that, as a pretty quiet older bochur, he felt bad that other bochurim around him were getting married and moving on, and so I tried to encourage him, to speak to him, but I didn’t dream for a moment that the worst of all was about to happen.”

Rabbi Breitkopf says that after the shock of the tragedy, it took a few days for him to remember : Yosef Dov Hy”d was obsessed with a will. Maybe he actually wrote one, and they should be looking for it?

“We searched and searched, but didn’t find anything. And then, three months later, we found it — buried between the folds of the pillow he used.”

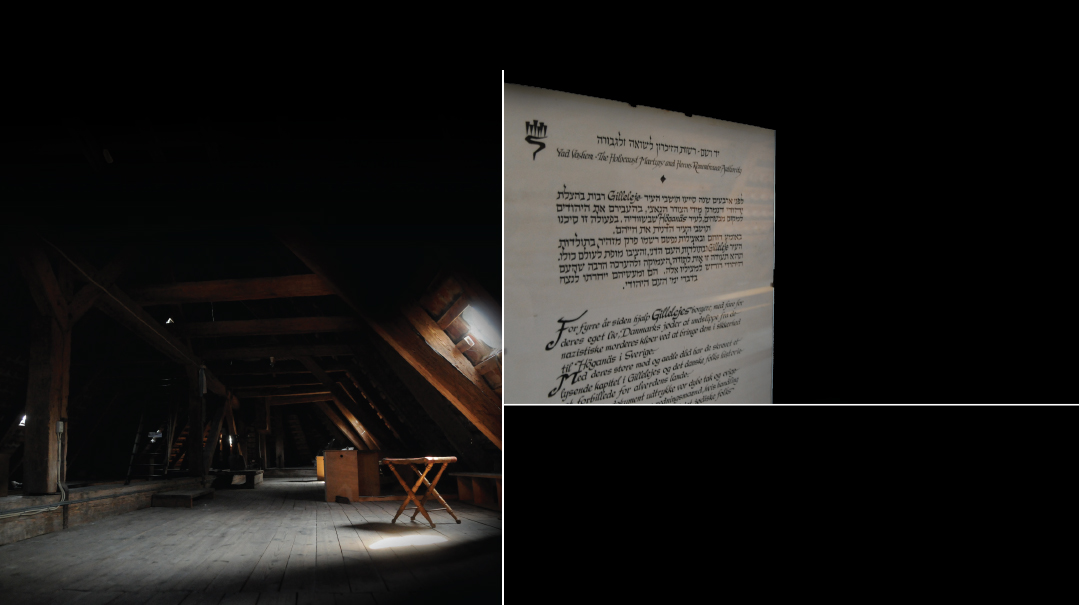

The will was found when the bed was given to a different student, who felt a rustle of papers in the pillow when he put his head down to sleep. The bochur opened the zipper and found two envelopes, on which were written Chadra”g — an acronym for “Cherem D’rabbeinu Gershom” who imposed excommunication on anyone who opened and read a letter addressed to someone else without that person’s permission. One envelope had the words “To my family” written on it, and the other had the names of two of the roshei yeshivah. Both documents were written and signed by Yosef Dov — on Motzaei Shabbos Bo, which was exactly 30 days before he died.

The Third Will

“Even today, 40 years later, no one can understand why Yossi merited to have such a revelation from Above that he was going to leave This World, and that he should understand that he had to write a will. But the wording with which he began the will says more about my brother than anything else,” says Attorney Esther Stern, Yosef Dov’s sister.

The will begins, “Sometimes a person merits to have a feeling as though he is going to die so that he should do teshuvah miyirah, perhaps Hashem gave me a bit of merit and I write this of my own free will… knowing that it is possible that I will soon be standing before the Heavenly Court.”

There were actually three wills — one for the roshei yeshivah, and two for the family. Yosef Dov had written two copies for his family (in case one copy got lost or was never found), stuffing one in his pillow and another in a book that happened to be in Mrs. Stern’s house.

“I was sitting at home in Jerusalem three months after the attack,” Mrs. Stern relates, “when a bochur named Yitzchak Levy knocked at the door. He was a good friend of Yossi’s, and I knew him from the years before I married, when he would come with Yossi to my parents’ house in Tel Aviv. He didn’t say much — he just wanted to know one thing: Did I have a copy of the book Chasufim Batzariach (Exposed in the Tower) that was released after the Six Day War? I thought it was a bit of a strange question, but I said yes, it was on one of the upper shelves of the bookcase.

“Levy didn’t waste time. He climbed up to the top shelf, took down the book, and leafed through it rapidly. Then he pulled out a bundle of pages and placed them on the table. ‘Here is the will,’ he said to me. I didn’t understand what the boy was talking about. ‘This is Yossi’s will,’ he tried to explain. I was in absolute shock. I didn’t understand what he was talking about. I took the pages and scanned the lines. Yes, it was Yossi’s handwriting, and he had written this will. A real, long, detailed will for the family, written in a tasteful way and very organized, as if he was an old man who was preparing for his last days on this earth.”

After the shock of finding the wills, Mrs. Stern realized something else that made her heart squeeze. “Throughout that month, Yossi bore his emotions in silence. What tremendous fortitude it must have taken not to let even a word slip to his parents and close family. Only his friend, Breitkopf, heard some remarks from him about his imminent passing, but even he didn’t understand what Yossi was talking about.

“You know, I often think how it was that Yossi merited to say Vidui and write a will with a clear head. It was a special revelation, but Yossi really was a special bochur. He came from a home that today they call ‘modern.’ Our father came from Romania, from Pashkaner chassidim. But he was also educated and worked as a publicist in Kol Yisrael and Shearim, and later as a lawyer. He did have a fiery Jewish soul though, and when Yossi chose a different path, my father didn’t hold him back. In fact, he even encouraged him. Yossi became very close to the Yeshuos Moshe of Vizhnitz, and like many yeshivah bochurim at the time, he would often go to the beis medrash of the Beis Yisrael of Gur. He had a chassidic soul and he was interested in spiritual matters — he was always busy with these things. He was quiet, but that didn’t stop him. He was involved in kiruv campaigns to register children for Torah institutions, and he was involved with chesed projects for unfortunate people from all over the country, without anyone knowing about it. He was a walking chesed institution.”

Learn for Me

Yosef Dov’s father, a respected writer, printed an essay on the back page of a special edition of Sefer Chofetz Chaim that he had prepared to mark the first yahrtzeit of his son. He wrote that he chose this particular sefer because one of the items in the will was that the family strengthen themselves in shemiras halashon. The essay, replete with searing grief and pain, conveys a message of acceptance of the decree with remarkable faith, and the father finds an explanation for his son’s revelation:

“Things make perfect sense with the words of the Ohr Hachaim on the pasuk ‘Vayikrevu yemei Yisrael lamus — and the days for Yisrael to pass away drew closer,’ in parshas Vayechi. The holy Zohar says that a person can sense his impending death 30 days prior. The Ohr Hachaim adds: ‘Although this knowledge is withheld from people, the tzaddikim sense and know.…’ ”

At the end, his father notes that before Yosef Dov left his home for yeshivah the last time, he left his parents a siddur. His father assumed he’d simply forgotten it, and therefore only opened it after he returned from the levayah. It was then that he saw the inscription, “To my father shlita, from his son, Yosef Dov, Shevat 5738.” It was his goodbye present.

“Yosef Dov was a very, very spiritual bochur,” Rabbi Breitkopf says by way of trying to explain how such a young bochur merited such a stark revelation from Above. “He was quiet and introverted, but he was a fire regarding any matter relating to kedushah. He would visit traditional shuls and ask the mispallelim to register their children to Torah institutions, something that in those days was no simple matter. He had gaavah dikedushah, pride in everything holy.”

Rabbi Breitkopf emphasizes that Yosef Dov didn’t come from a home of bnei yeshivah, but they were happy to send him to yeshivah ketanah instead of yeshivah high school. “In Ohr Yisrael where he learned, he became extremely close to Rav Yaakov Neiman, the legendary rosh yeshivah there. He had a special charm and impeccable middos, and that’s why everyone loved him, but he was also profoundly spiritual. He never touched his beard, which was very unusual in the yeshivah. He also immersed in the mikveh daily — which means he was tahor on the day he died.”

Rabbi Breitkopf shares one more remark that Yosef Dov made. “In the last month when he would speak openly about what he knew was his impending passing, he would tell me almost every day, ‘Go and learn for me, I can’t learn, I have too many thoughts on my mind.’ He also always offered to buy me whatever I needed in the grocery and the like, as long as I sat and learned for him.”

Well-known Yerushalmi journalist Reb Yisrael Gellis was at that levayah 40 years ago, and even made a recording of the father’s heartrending hesped. “I used to go everywhere with a small tape recorder,” Gellis says. “So I have the recording. Only 25 years later did I find out that the family was looking for the recording, and I was happy that I was able to give them this important memory.

“I knew Yosef Dov well,” Gellis continues. “We learned together in yeshivah, studying Maseches Sanhedrin. I was one of his partners in going out to persuade people to register their children for Torah schools. He was a special bochur and there were few like him. Several articles were written about him after his tragic death. But even 40 years later, his memory still lives on in the hearts of all those who knew him. Yehi zichro baruch.” —

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 701)

Oops! We could not locate your form.