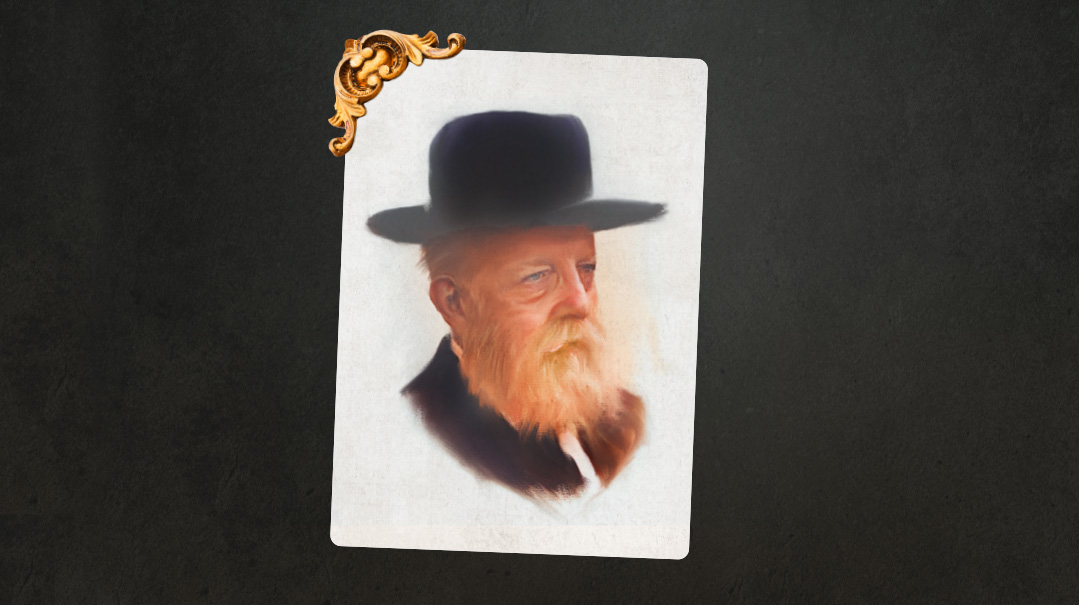

He Belonged to Everyone

The Skulener Rebbe, Rav Yeshaya Yaakov Portugal ztz”l

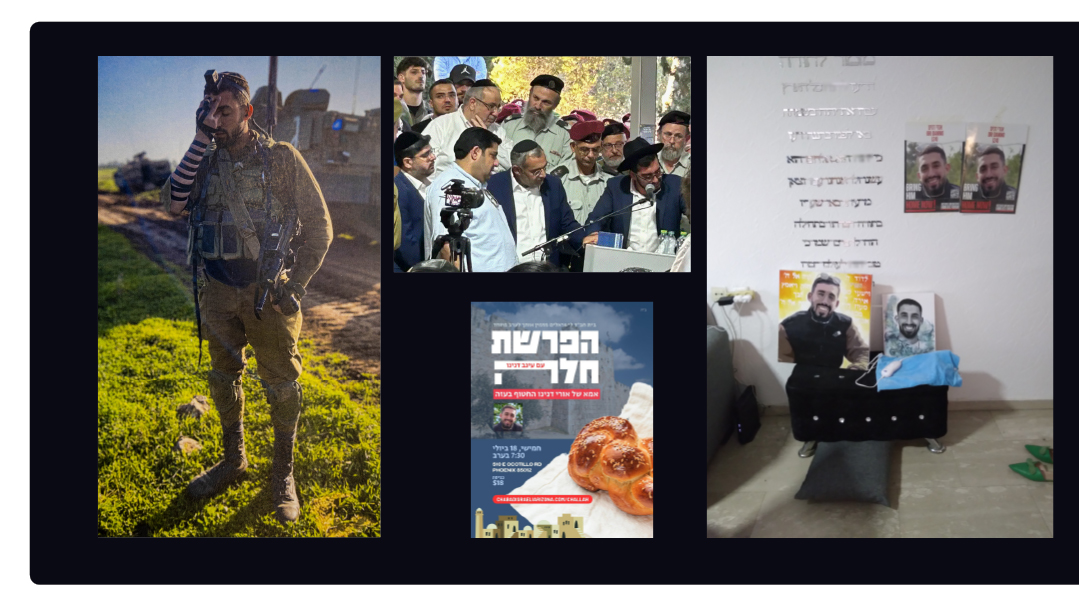

Photos: Meir Haltovsky

His father understood that this neshamah would best grow and develop in freedom. And then in 2019, the Skulener Rebbe, Rav Yeshaya Yaakov Portugal, ztz”l, was plucked away from his unassuming life in Montreal to assume the mantle of leadership

There was a man who lived in Montreal, a thin man with a black beard and glasses who learned in kollel all day.

If you spoke to him, he would stoop forward in humility, bending toward you to let you know he was all yours, in the manner of the Amshinover Rebbe or Rav Asher Arieli.

You could see him walking the streets. If you happened to be driving, and you pulled over to offer him a ride, he might take the glasses out of his pocket, squinting through the car window and see who it was.

His face would light up when he saw that it was you — whoever you were, because you were a Yid, and that was reason enough for joy. If he accepted the ride, he would climb into the car and shower you with brachos, telling you just what a favor you were doing, making you feel like your car coming down the street at this moment was an act of kindness unequaled since the moment of creation.

Morning often saw him circulating in local shuls — “gein noch gelt,” collecting for a Yid facing hardship: different days, different Yidden, different tzaros.

It might be a Yerushalmi meshulach who just didn’t have a knack for collecting, a local Yid who was overwhelmed by chasunah expenses, or someone he had met the night before. On Rosh Chodesh, he would go from shul to shul, collecting for Chessed L’Avraham, the organization founded by his grandfather to provide for the spiritual needs of immigrants to Eretz Yisrael.

Hand outstretched, he would approach, accept the five-dollar bill with his glowing smile, and leave the giver with a hail of brachos.

One morning, I saw him come into the Dzibo beis medrash in the Uptown neighborhood just as davening ended. Most of the regulars knew exactly who the slim man with the radiant face was, but one Yid, eager to get to the last of the cheese Danishes and rapidly dwindling Old Williamsburg bottle, said, “I just gave you last week!”

It was uncomfortable. This wasn’t a random collector looking for lunch money, but a genuine tzaddik, son of a tzaddik, grandson of a tzaddik, collecting for a different cause than the one the previous week. (And who knows how many other causes there had been between the two?)

“Ahhh,” said the tzaddik with the outstretched hand as he flashed a grateful smile, “takkeh, indeed. Tizkeh l’mitzvos, you should be gebentsht.”

Then he continued his dance through shul, through life.

What a beautiful person.

Then, Rav Yisroel Avrohom Portugal, the Rebbe of Skulen, was niftar, and this Yid from Montreal was plucked from this existence, crowned as Skulener Rebbe in his father’s place.

HE

was not just a successor; he was consolation.

The first Skulener Rebbe, Rav Eliezer Zusya Portugal, served as rav in Sculeni, Moldova (present-day Ukraine), leading the townspeople with love and warmth. He wrote booklets for them in Yiddish, was able to communicate with them on their level and open their hearts. At the direction of the Sadigura Rebbe, he moved to Chernowitz, where he continued to draw people close. When World War II ended, Rav Eliezer Zusya did not seek to leave Europe; rather, he opened an orphanage for the many, many children who had lost their parents.

He settled in Bucharest, Romania, with these children, and he and his son Rav Yisroel Avrohom tried to teach these orphans about where they came from, and what it means to be a Jew.

With the ascendance of the Communists, it became forbidden to teach religion in Romania, and the Rebbe and his son were arrested, imprisoned, and tortured for their crime.

The plight of these two tzaddikim inspired an international diplomatic effort to win their freedom, and in 1960, they were released and allowed to leave the country.

They arrived in America, but Rav Eliezer Zusya did not open a yeshivah, as was expected: America had enough yeshivos, he said. Instead, he established Chessed L’Avraham, an educational and social services network that would service the families of those immigrants from Ukraine and Romania who were arriving in Eretz Yisrael. This way, the Rebbe said, he could continue to take care of his people and draw them close.

When Rav Eliezer Zusya was niftar in 1982, Rav Yisroel Avraham became the new Skulener Rebbe. He too had been beaten for refusing to bend, and he too had managed to create song — such beautiful songs, pesukim of courage and resilience coming alive! — while the blows rained down.

This is my comfort in my affliction, for Your word preserved me. Willful sinners taunted me exceedingly, but I did not swerve from Your Torah.

MiToras’cha lo natisi….

Rav Yisroel Avrohom would become a “Rebbe’s Rebbe.” There were very few natural Skulener chassidim, for this was not a dynasty with a rich history, but masses of Yidden found their way to Skulen, seeking brachah, seeking elevation, yearning to be in the presence of the pure tzaddik.

Many stayed, and the beis medrash on 54th Street in Boro Park filled up. It was a Klal Yisrael chassidus, and Rav Yisroel Avrohom became a Klal Yisrael Rebbe, his last great campaign resulting in the Kinus Klal Yisrael, a gathering to give people the strength and spirit to face the looming nisayon presented by technology.

He was the Zekan Ha’admorim, the last remnant of a generation of Rebbes who carried the scars, sacrifice for other Yidden evident on their bodies. He hovered in a dimension of his own, above time, above space, but very present, his whispered brachos giving life and hope where there was none.

And then, in the spring 2019, he was taken, and the consolation came in the form of his beloved eldest son.

Reb Shaya Yankel, as he was known.

The Yid hurrying through the streets of Montreal.

HE

had been born in Bucharest in 1956, raised in Crown Heights. He attended the Satmar cheder. His classmates knew not to come late, because the melamed was strict about punctuality, but Shaya Yankele was an exception. If he came late, the rebbi said nothing.

The boys asked why he was different, and the rebbi explained. “If you were to see him daven, you would understand.”

From there, he went to learn in the Ruzhiner Yeshivah in Eretz Yisrael. There, he would slip away to light Chanukah lecht in seclusion, hoping to remain unseen. Bochurim, however, being bochurim, followed, and until today, they recall the intensity and power of the maamad, the hadlakas neiros of one bochur, alone, before an audience of One.

Whatever the setting, this diamond shone: Pure, joyous, humble and kind, he was both beloved and respected.

He was a masmid, accomplished in learning, but somehow had time to see and hear others, a friend to those desperate for a smile and a listening ear. It was clear that a rebbishe kind was developing, and his grandfather, the Noam Eliezer, articulated it.

When his time came to stand before the Heavenly Court, said the Noam Eliezer, he would have no zechuyos, no obvious sources of merit — but one. “I will tell them that I am the zeide, the grandfather, of Shaye Yankele and they will welcome me!”

The bochur came home and became a chassan. Rebbetzin Silka is the daughter of Rav Mayer Grunwald, a grandson of the Arugas Habosem.

He had served as rav in Teitch (Tyachivo), Hungary, before World War II, during which he had lost his wife and the majority of his kehillah. In 1949, he opened a shul in Toronto, and built a new family, along with his second rebbetzin.

The Teitcher Rav was niftar at the age of 56, and his rebbetzin married again, to Rav Yitzchak Eizik Moskowitz, rav and rosh yeshivah of Meor Hagolah in Rome, and later in Montreal.

Like Reb Shaya Yankel, the kallah had been raised by people who sacrificed for other Yidden, and it was a suitable shidduch.

Reb Mordechai Friedman, pillar of the Skulener chassidus for decades, recalls joining the Noam Eliezer for matzah-baking that year. The Rebbe would never mention a personal need, but the gabbai informed Reb Mordechai that there was no money for the upcoming chasunah.

Reb Mordechai pledged to take care of it, and later on, the Rebbe remarked on his generosity. “I heard what you did,” the Rebbe said. “Today, not too many people know about my Shaya Yankele, but one day, the world will know who he is.”

T

he years passed.

The beloved scion of Skulen raised his family in Montreal, a member of the Belzer kollel. He became especially close with the rav of Montreal’s Belzer kehillah, Rav Yaakov Yitzchak Neumann, from whom he earned semichah.

After the passing of Rav Eizik Moskowitz, Rav Shaya Yankel assumed leadership of the small Meor Hagolah shul. At some point, he joined the Skverer kollel, joining in the other yungeleit in taking bechinos, mastering large sections of Shulchan Aruch.

His zeide was niftar and his father became Rebbe, but still, he did not move to New York.

Clearly, he was bound heart and soul to his father, traveling regularly to spend Shabbos with the Rebbe, but he stayed in Montreal.

In the presence of his father, he sat bent over, subservient, and when he walked away, he did so while facing his father — yet he lived in Montreal.

A friend of mine, a Tosher chassid from the Five Towns, was traveling to Tosh for Chanukah lecht one night. In the airport, he saw Reb Shaya Yankel, also heading to Montreal.

After greeting him, my friend received a call on what was then a novelty — a cell phone. Reb Shaya Yankel noticed and asked if he too might make a call on the flip phone.

He took a small cup out of his bag, headed to a water fountain and washed his hands. Then he tightened his gartel — that was itself a scene, to watch him trying to tighten a gartel around a body so thin it could barely sustain its own weight, nothing to hold that gartel in place — and adjusted his hat.

Then he dialed, standing reverentially with his eyes closed.

“Shaya Yankele, is everything okay?” his mother’s voice came through the phone.

“Yuh, yuh, Mamme, I just wanted to ask the Tatte, the Rebbe, for a brachah.”

A moment later, the raspy voice of the Skulener Rebbe came through the phone.

“Tatte, forgive me, I just want to ask for a brachah to come home safely on time to light the lechtelech, and a brachah to be an erliche Yid.”

A father and his son, a language of their own.

Why, then, did the Skulener Rebbe marry his son off to a girl from Montreal, agreeing that his son would start married life there?

Because his father knew what he had!

He understood what Reb Shaya Yankel was, and that this neshamah would best grow and develop in freedom: a pillar of tefillah free to stand in any shul, at any time of day, and cry; a talmid chacham free to toil in Torah on plain wooden benches, taking tests alongside other yungeleit; and a master of chesed free to grab chasadim and help Yidden not by receiving them in his study, but by searching them out.

There, out of the limelight, a tzaddik was growing ever so tall.

A

local medical askan told me how a certain patient needed emergency surgery at three o’clock in the morning. The patient would not agree to the procedure unless Reb Shaye Yankel agreed to it.

“The doctors want an answer now,” the askan told him, “and they won’t wait until morning.”

The patient looked up from the bed and pleaded with the askan, “Trust me, he’s up. You can go ask him. He’s either learning in Meor Hagolah or he’s learning at home, but he’s up.”

Montreal has all sorts of chassidim, Satmar and Belz, Skver, Vizhnitz, and Munkacs. There is a yeshivah community, a Lubavitch community, and a Sephardic community.

He belonged to everyone.

People started to come over on Leil Shabbos after the seudah for a botte, an informal gathering. It started with just a handful of people, just over a minyan, several of them walking from the Uptown neighborhood.

During the week, people came through his house for brachos, but like the botte, there was nothing formal about it — no waiting rooms, no gabbaim, and no Rebbe.

You might catch him in the house, but it was just as likely that you would catch him in one shul or another, that he would be standing on a random street corner engaged in a mitzvah known only to him, and you would be the lucky one to drive him to his next stop.

A family was visiting Montreal for a Shabbos sheva brachos, and they were being hosted by one of the neighbors of the mechutanim — the Portugal family. After the Friday night sheva brachos, the family returned to their lodgings.

They had eaten, sang, and danced. There had been drashos and the actual sheva brachos. Hours had passed, but Reb Shaya Yankel had not yet made Kiddush. It took him a long time to be ready to lift the becher and say “Yom Hashishi.”

But in the middle of those holy hachanos, his guests came home and he stopped what he was doing. He hurried to greet them, welcoming them to his home, and then, he danced with them, sharing in their simchah.

The lofty preparations waited while he rejoiced with them. Or maybe, after all, that joy was part of how he prepared for Kiddush?

His father was the Rebbe. He was just a Yid with eyes that laughed when you were happy and drooped when you were not, who loved you because you were a Yid, and in his sweet whisper, he reassured you that everything would be okay — despite what doctors said, what lawyers said.

Sure, there were mofsim. I have close friends, people with real names and phone numbers who were told “darfst nisht zorgen, you have no reason to worry,” and saw results that mystified doctors, but that’s not the story here.

The brachah was in looking at him. In being around him. That itself was the gain.

He was not a well man, and about 12 years ago, he was in critical condition, in need of a kidney transplant.

Miraculously, it happened, and Reb Shaya Yankel started to get his strength back.

After several months, the doors were opened for the weekly botte.

The people came and they were concerned, the tzaddik looking pale and weak. Then he started to sing zemiros, and with each phrase, each expression of praise for Shabbos Kodesh, he seemed to grow stronger.

He sang of the Creator, and he himself was newly created, color returning to his face as he sang the song of Shabbos.

“That night,” recalls a friend, “we saw a Yid nourished by his dveikus in the Borei Olam.”

A

precious personal memory. When my grandfather passed away, my parents moved from Montreal to New York.

Reb Shaya Yankel came to bid my father farewell, and he recalled how once, while driving him, my father had shared a vort from Rav Yosef Yitzchak of Lubavitch.

There is a tradition that every Yid carries the letters of the Sefer Torah imprinted upon him; but these letters are not merely written, ink on parchment. Rather, the letters are engraved on the Yid: not kesivah, but chakikah, the holy letters of Torah seared onto the Yid.

The difference, said Rav Yosef Yitzchak, is that ink can fade from parchment, but engraved letters can never get erased. They might get filled with dust, but dirt can be easily wiped away.

Reb Shaya Yankel repeated the vort with enthusiasm, saying that he would always be makir tov for having heard it.

It was one more insight into the greatness of a Yid, a gift to one who cherished Yidden.

T

he world lost the old Skulener Rebbe and Montreal lost Reb Shaya Yankel.

In anticipation of the first tish of this new Skulener Rebbe, the block of Boro Park’s 54th Street, outside the Skulener shul, was closed off and a tent erected to hold the crowd. By the time the Rebbe came out for Kiddush, it was clear that the tent would not be able to hold the people, nor could it contain their emotion.

The slim, slight Rebbe stood erect, as if aware that so many hopes were pinned on him, this pure tzaddik who had made it about helping Yidden, uplifting Yidden, and elevating Yidden.

The years that followed were not simple ones.

Covid created panic and devastation, and it was followed by a string of national tragedies, heartache, and pain.

He was there to provide reassurance and comfort, just as before.

Now, he was no longer able to roam freely between shuls, but the spirit was free as ever.

At the tish, he could still quote Torah he had seen from the Rachmistrivka Rebbe or Reb Meilech Biderman, as if he was in his dining room addressing a handful of people.

A friend of mine from Montreal was marrying off a daughter. The new Skulener Rebbe welcomed the baalei simchah, then danced a private mitzvah tantz before the chassan and kallah.

“And that dance, in his room, was exactly the same as the mitzvah tantz at my older daughter’s wedding,” recalls the baal simchah. “Then, it was in a hall, before a large crowd, with music, while here, it was just a few of us, in his private room — his intensity, his elegance, and the kedushah he radiated was the very same. We still had him.”

When chassidim from Montreal, those who had once braved sub-zero weather to walk to the botte in his dining room, would come to Skulen in Boro Park, the new Rebbe would urge them to go say hello to the Rebbetzin. There might have been gabbaim, a long line, and a waiting room, but nothing had changed.

He faced one health challenge after another, hovering between two worlds, but we had him.

And now, he has slipped away.

This blow is devastating, coming when it does, at a time at which we are so vulnerable.

The Verdaner Rebbe, Rav Yosef Leifer, was an aged tzaddik, a scion of Nadvorna. He was niftar during the first dark days of Covid, and at his levayah, a kvittel was slipped into the aron.

We, the impoverished ones signed below, ask the tzaddik to intercede for us before the Kisei Hakavod, asking that this mageifah be stopped before Yom Tov, that we should be able to receive the Yom Tov with happiness, as is fitting, that the tinokos shel beis rabban should be able to go back to learning Torah and we should be allowed to daven with minyan.

See our affliction and pain. Our eyes are raised, waiting for the yeshuas Hashem and His abundant mercy.

It signed by Rav Yechezkel Roth, Rav Yeshaya Yaakov Portugal of Skulen, and Rav Shraga Feivish Hager of Kosov.

The Skulener was the last of the three tzaddikim who was still here; now, they are all gone.

Let this be a kvittel. Let them stand and plead for all of us, a nation that lives in fear, a lone, quivering sheep surrounded by wolves.

And if we have sinned?

Remember this, Skulener Rebbe: The letters that make a Yid holy are not written, but engraved, hewn into our essence.

We just have to wipe away the dust and it is clear. We are Yidden, and you taught us that this itself makes us worthy.

As you once asked, so do we.

Yom Tov is coming again. Let us receive it in joy.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1028)

Oops! We could not locate your form.