With Toil and Truth

Rav Dovid Soloveitchik didn’t remain in the past, but neither did he veer from his message of emes and the uncompromising derech of Brisk. Yet his was also a journey of joy, warmth and love — the very life-force of Torah

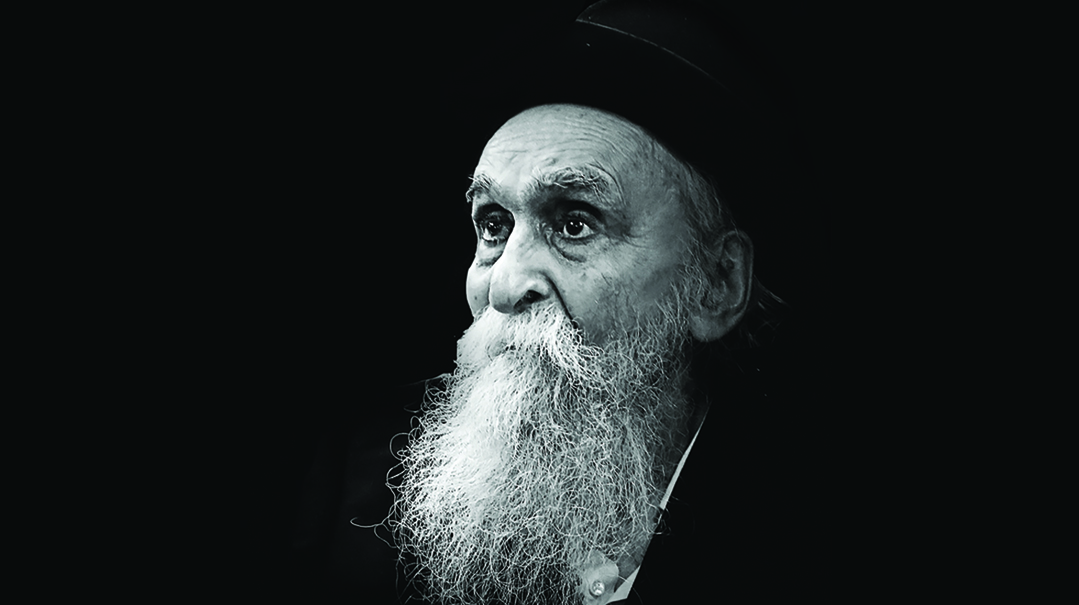

Photos: AEGedolimphotos.com, Shuki Lehrer, Mishpacha archives, Rabbi Shimon Yosef Meller, author of HaRav MiBrisk

There were many words I would have used to describe the apartment.

To me, it was, first and foremost, intimidating. I came with nothing except an assurance from my rosh yeshivah in America that I was on the reshimah for the new zeman, but there was no confirmation number or bar code to prove it.

On the morning of the first day of Rosh Chodesh Elul we gathered, a cluster of jetlagged new arrivals in shirts that were still crisp and white from the American dry-cleaners, standing nervously outside Amos 28, waiting for the door to open. We made small talk — where’s your dirah, how does the money-changing thing work, does Rav Dovid expect you to say a shtickel Torah? — when at precisely 11:00, the door was opened by the Rosh Yeshivah himself.

Rav Dovid Soloveitchik, in a large yarmulke and blue silk robe, with eyes as pure and clear as those of a child.

The line started to move, one bochur after another, and eventually my turn came. The room — where Rav Dovid learned, ate seudos with his family, said shiur — was austere. Steel-frame bookcases sagged under aged seforim; pictures of the Beis HaLevi, Rav Chaim, and the Brisker Rav seemed to be waiting for the handyman to come hang them in a more permanent location; and a few plain wooden chairs stood around the table.

He consulted a tiny paper — the actual reshimah — and, searching with a Parker Pen, confirmed that my name was there, and I was officially enrolled in yeshivah.

Gut. Good.

Rav Dovid’s yeshivah, back then, wasn’t much for formality.

First seder was in the Kerem shul, down a long road at the Western tip of Geula that seemed more like a driveway with a few hut-like homes lining it, some with real chickens walking around in the front yard. Rav Shach, it was reported, had spent all day learning in that shul, at a different time. Now it was used by Rav Dovid’s yeshivah and you had to climb up a steep staircase to the entrance, then climb over people to get to your seat, as if it were the middle row in an airplane.

Fresh-faced Americans said “anshuldigs” as they made their way over unflustered Israelis and squeezed through groups of hard-edged Yerushalmim, a delicate dance of mutual respect around the circular grate surrounding the raised bimah. On one part of the hexagon-shaped bench sat Rav Velvel, the Rosh Yeshivah’s son and newly appointed successor.

Second seder was at the Amerikaner shul in Zichron Moshe, an overstuffed room that was either freezing or over-heated, depending how closely you were seated to the heater. Shiur was in a third location, an apartment gifted to the yeshivah by a widow who asked that Torah be learned between its walls, in an oddly shaped room featuring seats in which you could see but not hear, or the opposite.

This was Yeshivas HaGrama’d, the yeshivah of Rav Meshulam Dovid Halevi Soloveitchik. And somehow, the various outposts and diverse talmidim were joined, if not by background, style, or even substance, by shared allegiance and devotion to the Rosh Yeshivah.

His home was open. We went there once a week for Chumash shiur, once a month for “chalukah” (the stipend given to talmidim in the yeshivah since the yeshivah’s founding in Europe), and talmidim were invited to join the Rosh Yeshivah for Krias HaTorah at his home-based minyan on Mondays and Thursdays.

The apartment itself took on all the dimensions of the yeshivah it served — the passion and fervor, the reverence and awe, the authenticity and truth — but years later, I found the single word to describe it.

It came from a letter written by Rav Moshe Shmuel Shapira, a talmid and relative of Rav Dovid’s father, the Brisker Rav, in which he described the atmosphere in his rebbi’s home.

“Each day,” wrote Rav Moshe Shmuel, “I learn at the joyous home of the Brisker Rav.”

It was a joyous home.

And the four amos of Rav Dovid Soloveitchik were a joyous place to be.

Because in the precision and punctiliousness of Brisk, the zeal for halachah and the near-tangible fear of Heaven, Rav Dovid revealed the neshamah, the warmth at the core, the life running through the dinim.

And so his talmidim, spread across shuls and later, continents, loved him so — a love that continued until his very last day.

And now they are bereft.

The winds of World War II separated the Brisker Rav, Rav Yitzchak Zev Soloveitchik, from his rebbetzin and younger children, who did not survive. Along with several of the older children, he made his way to safety in Eretz Yisrael in 1941. From his apartment on Rechov Press in Jerusalem, he took his place as one of the leaders of the reborn yeshivah world in Eretz Yisrael. But from the outset, there was something different about him and his family.

Rav Leizer Yudel Finkel, the Mirrer rosh yeshivah, once left some money on the table of the Brisker Rav, suggesting that the Rav’s sons — with their old-fashioned caps and suits — might benefit from new clothing in the style of the local bochurim, since they appeared very different.

“Yes, they do appear different,” their father replied, “because they are takeh different.”

But even in this group of soldiers, distinct in dress and comportment, 20-year-old Dovid stood out. Once, Rav Dovid confided to a talmid that he had expected to have arichus yamim because “I was meshamesh der Tatte with mesirus nefesh, making sure to be awake when he woke up and to stay up until he went to sleep.”

And being meshamesh der Tatte meant, first and foremost, being able to speak in learning with the Brisker Rav.

Rav Dovid once recalled how as a young child, one Leil Shabbos he had been sent by his father to get some seforim when people came to speak in learning. The room was dark, and it took some time to find the right sefer. “Der Tatte wasn’t satisfied, he told me that when he was a child, his father would send him for seforim and he found them immediately. Seforim, he said, should be recognizable right away, just by feeling them.”

“Der zaide (Rav Chaim Brisker) would wake up der Tatte and ask him deep kushyos, training my father to lig in lernen,” Rav Dovid related to talmidim, “and my father did the same to me. He would ask me complex questions about the sugyos he was learning, even if I wasn’t learning them at the time, and he didn’t care for excuses. Once, he asked me a difficult kushya on the sugya of tumah retzutzah and I told him that I wasn’t at all holding in that sugya, and I would have to look it over. ‘In that case,’ he told me, ‘I have nothing to discuss with you.” For several days after that, I felt his displeasure.”

This was the way in the joyous house of the Brisker Rav — the joy of toil, the joy of accomplishment, and the joy of living the truth.

The home on Rechov Press was also a yeshivah, much like the Rav’s home in Brisk had been, and his sons were among the talmidim. In time, the light of that apartment would radiate throughout the Torah world, but during those first years, the home primarily drew accomplished talmidei chachamim.

But in time, younger bochurim from the nearby Chevron and Mir yeshivos would come with their questions and the Rav’s third son, Dovid, displayed the ability not just to answer, but also to encourage. He would speak in learning with these teenagers, one of them telling the tale for all of them. At Rav Dovid’s levayah this week, Rav Boruch Mordechai Ezrachi — who’d been a young boy with obvious abilities but no clear direction — recalled Rav Dovid’s warmth and interest during those years, and he cried out, “Rav Dovid saved my life. He saved me!”

Reb Asher Sternbuch of London had been a successful businessman and a respected talmid chacham before passing away at a young age, leaving his wife with nine orphans. Her husband’s tragic passing shook the foundations of her home and family, but Devorah Sternbuch didn’t waver.

She would visit her husband’s kever and cry out, “Ribbono shel Olam, there are three shutafim in every human being: You, the father, and the mother. You’ve taken away one of those partners, so now You have my husband’s share as well. The children are Yours. Help them!”

All nine Sternbuch children would rise to greatness. One of them, Rebbetzin Yehudis, took her place as a life partner to the son of the Brisker Rav, Rav Dovid.

She came from a wealthy home and was accustomed to attractive furnishings. In her father-in-law’s home, however, even convenience was viewed as luxury, and from the moment of her marriage until this very day, the Rebbetzin adapted to her husband’s way.

Life for the new couple revolved around the Brisker Rav, his Torah, his dikduk hamitzvos, his hashkafah. After the petirah of the Rav in 1959, Rav Dovid started to say chaburos to bochurim, but not within a formal yeshivah. Later in life, when Rav Dovid had thousands of talmidim and was delivering several weekly shiurim on various parts of Shas, he would speak of those years — the 1960s and 70s — with longing. Back then, he’d been free to sit and learn.

And to learn, in the world of Rav Dovid Soloveitchik, meant something different.

“This world is filled with nisyonos, and there is only one solution,” he would tell his talmidim, “only ameilus b’Torah. Only real yegiah can close off your mind to Olam Hazeh.”

Then Rav Dovid would share a story. “Once, a group of bochurim came during the zeman to speak in learning with my father. Der Tatte asked them what they’re learning and they answered, ‘Maseches Gittin.’ He asked them where they were holding and they said ‘daf chof.’ Der Tatte said, ‘In middle of the zeman and you only did 20 blatt? You’re not learning Gittin, you’re learning zich — you’re immersed not in the masechta but in yourselves, your own comforts.’

“Here, we are going to learn Torah.”

In the late 1970s, the group around Rav Dovid coalesced into a yeshivah. Even after they got married, his talmidim didn’t want to part from him: They wanted to hold on to the Torah of Brisk, the dikduk of Brisk, the chavivus hamitzvos of Brisk, but with so much hartz, such passion.

The shiurim were clear and perfect. The yiras Shamayim they experienced just by observing him was vibrant and alive. Rav Dovid would become a rebbi in tefillah too — not just in formal tefillah, but in dveikus, cleaving to the Divine. When his talmidim sang, his face would be suffused with longing and hope.

He belonged to his talmidim, and his door was open to them. Most came to speak in learning, while some came for financial help, and it seemed he was always raising money for one yungerman or another. And others still came to unburden themselves, to share personal problems.

I recall the Rosh Yeshivah entering the Kerem shul one morning during first seder, umbrella in hand, and seeking out a certain bochur. Together, they left.

It turned out that a married talmid had confided in the Rosh Yeshivah that his wife was ill. So Rav Dovid asked a bochur who had a car to drive him directly to Meron, where he spent hours saying Tehillim.

And how he davened! A close talmid, who often accompanied him on these secret tefillah trips to Kever Rochel or Meron, remembers the process. Reb Dovid had lists of names of talmidim and their needs, and after he finished saying Tehillim for them, he would simply cry. He explained to his talmid that Chazal tell us that the gates of tears are never closed.

He compared this to a locked door, protected by guards who will only allow in those they recognize. Familiar people will knock and say their own names to get entry. “The gates of Shamayim open for those they recognize, so you need a name. But the gates also open for tears, which always unlock the doors, even with no names — so I need those tears for those whose names I do not know.”

He would daven for Klal Yisrael, spilling tears for people he never met, crying most of all for the glory of the Shechinah. On Rosh Hashanah, he received maftir, and when he reached the words “Al kiso lo yeshev zar, velo yinchalu acheirim es kvodo — On His throne let no stranger sit and let no other inherit His glory,” he would break down, barely able to continue.

When the talmidim sang on Yom Tov, his eyes would often fill with tears. At the age of 98, his face was still colored with yearning when he sang “Vetaheir libenu le’avdecha be’emes” during hakafos — the man of truth desperate for a bit more truth.

Emes was his essence. During a difficult period, a wealthy American visitor came with a donation. It was an ordinary foundation check, rather than a personal check. Rav Dovid eyed it suspiciously, then told the donor he was grateful, but he didn’t understand how it worked and couldn’t accept it.

That emes that emanated from him explains how he was outspoken and unequivocal in his rejection of the modern state, opposed to the idea of frum members of Knesset, even as many of his closest talmidim are children of those same politicians. They all appreciate his honesty, knowing that he speaks with no agenda, determined to share the truths he’d received from his own father.

He took public positions against the gedolei Yisroel associated with the Degel HaTorah party, and I remember being confused, as a bochur, by this: I had a friend on the bench across from me, his last name was Steinman — first names weren’t a big thing in yeshivah — and he was getting married. From his wedding invitation, I learned that he was the grandson of Rav Aharon Leib — the gadol whose approach differed radically from Rav Dovid’s in so many ways. At the chuppah, Rav Dovid — his rebbi, and the rebbi of his father — argued with Rav Aharon Leib, the zeide, each one insisting the other serve as mesader kiddushin.

By Rav Dovid, love and truth merged.

His mechutan, the father-in-law of Rav Velvel, is Rav Berel Povarsky, who also serves on the Moetzes Gedolei Torah of Degel HaTorah. Whenever Rav Berel came to visit, it was Yom Tov, Rav Dovid reveling in his mechutan’s Torah and casual conversation.

A bochur asked Rav Dovid what his father had held of a particular rav, calling the controversial talmid chacham by his last name. Rav Dovid ignored the question. The bochur tried again, and Rav Dovid didn’t react. The third time, the bochur added the title “Rav” before saying the last name. This time, Rav Dovid turned to him. “By my father, we didn’t talk about people, only about ideas.”

Not only did the emes not offend, it uplifted.

The room was crowded during the Neilas Hachag one Yom Tov when a prominent supporter of the yeshivah walked in. Rav Dovid stood up, looked around the room for an empty seat, and then apologized to the donor, saying there was no seat. The visitor nodded, and stood along with everyone else, listening to the rosh yeshivah’s Torah. Several minutes later, a talmid of the yeshivah, a great talmid chacham in his own right, entered the room — and Rav Dovid excused himself and went to the kitchen. He came back a moment later carrying a stool for the new arrival, a show of kavod haTorah.

Over the last 40 years, Rav Dovid showed a different side — the fierce love for his talmidim.

A big part of the chinuch in Brisk was in commitment to mitzvos. You can feel when it’s mayim shelanu day, and kisui hadam is an opportunity to seize. Choosing daled minim and baking matzos are major annual rituals, and early on, the invitation was issued to the American bochurim staying in Eretz Yisrael for Pesach: They were welcome to join the Rosh Yeshivah at matzah baking.

On Rosh Chodesh Nissan, Rav Dovid, along with his brothers and nephews, took his place near the oven, anticipating the end of a process that had started months earlier. (Later in the day, the precious, fresh-baked matzos would be driven home from the Meah Shearim bakery in a car, one passenger charged with holding them, and Rav Velvel walking along behind the car just to make sure everything was in order.)

The various bochurim who came were given jobs and, with the seriousness of a surgeon at the operating table, Rav Dovid presided over the chaburah, watching every move as heat from the oven and tension from the people fused in the room. At one point, one of the talmidim brushed a matzah with the sleeve of his sweater, and one of the family members ran to tell Rav Dovid.

“Nu, nu,” said the Rosh Yeshivah, and wrapped that matzah in a paper and wrote, “nagah b’beged” on it before placing it in the box with the other kosher matzos. A few minutes later, the bochur, feeling uncomfortable about his mistake, said that he was leaving and handed his job over to someone else.

Rav Dovid saw that the bochur was going and left his own position, walking the young man to the door to see him off and telling him, “You did good today.” Finally, he gave the talmid a warm brachah and they parted.

The bochur walked back to his dirah beaming, and when his friends asked him why he looked so happy, he told them what had happened.

One of the older talmidim shook his head. “There is no way the Rosh Yeshivah is using that matzah, it makes no sense.”

The next day, this talmid investigated and came back with his report. The matzah had quickly been tossed once the bochur had left the bakery, but Rav Dovid — completely focused on his wheat and the precious matzos it would become — had somehow noticed that the American bochur had felt silly about his mistake, and made sure to send him off feeling good.

This ability to match his devotion to the mitzvah and his devotion to sensitivities of others was evident one year during bedikas chometz. He performed an exhaustive bedikah along with a few dedicated talmidim, spending hours searching through his small apartment.

One of the talmidim saw something under the seforim shelf and reached in to pull out a small piece of Lego. Rav Dovid’s face blanched.

“Rosh Yeshivah, it’s just a toy,” one of the talmidim said.

“Yes, but if a small toy could be under there, than a small piece of chometz can be under there as well,” he answered. “It means it wasn’t cleaned.

“Yehudis,” the Rosh Yeshivah called out, “please come quick.”

The Rebbetzin came in, and Rav Dovid showed her the Lego.

She smiled. “Rav Dovid, it was cleaned, don’t worry, we moved the seforim shelf, there’s nothing there. But remember our little einekel came to visit earlier today and he was playing here? He was using this toy, and it fell under the shelf after it was already cleaned. You have nothing to worry about.”

He nodded, at peace, and the Rebbetzin left.

Then Rav Dovid closed the door and turned back to his talmidim. “Okay, but lemaiseh we have to clean again now, so let’s move the shelf,” he said quietly.

Talmidim who had moved to chutz l’Aretz would often come visit when they were in Eretz Yisrael. It was a high point, the Rosh Yeshivah and Rebbetzin gracious hosts as they looked at pictures of children and offered brachos.

Those talmidim who’d succeeded in business would try to give the Rosh Yeshivah money. Inevitably, he would say he was collecting for one of the yungeleit or take the money for the yeshivah: For himself, he was hesitant to accept anything.

Then, he would thank the talmid but point out that pursuit of business and more money is futile, and he hoped his visitor was learning seriously, because that was the only important thing in life.

Once a talmid who had become a popular singer came to visit.

“Vulliger, ich hub ta’anos oif eich — I’m upset at you,” Rav Dovid told the surprised visitor.

“Why is the Rosh Yeshivah upset with me?”

“Because I saw a poster on Malchei Yisrael for a concert and your name was there, which means you came and didn’t visit,” the Rosh Yeshivah responded.

The singer explained that the concert had indeed been advertised, but then it had been canceled and he hadn’t come after all: Of course he wouldn’t miss a chance to visit the Rosh Yeshivah if he were in Eretz Yisrael.

Rav Dovid was satisfied.

One of the talmidim went hiking during bein hazmanim and broke his leg. He was laid up in Shaare Zedek and had a visitor: the Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Dovid, who came bearing a container. He knew American bochurim like ice cream, so the Rebbetzin had prepared homemade ice cream for this talmid. Love for a talmid and the love of chesed that defines Brisk lit up the Rosh Yeshivah’s features as he shared the gift.

A young Moroccan talmid chacham had learned in Gateshead and succeeded. His rebbeim thought he was ready for Brisk and sent him to Jerusalem. Being unfamiliar with the city and its inhabitants, he asked for directions to Rechov Amos and wandered around, asking if anyone knew Rav Dovid.

One man invited him home and insisted he enjoy a hot tea, and then they could worry about Rav Dovid. Only after the new arrival felt like a person again did his host introduce himself as Rav Dovid Soloveitchik.

The respect for his talmidim extended to his expectations from them: They were no different from children.

A young man had taken a short-term position as a mashpia in America, and he came to receive a parting brachah from the Rosh Yeshivah. Rav Dovid wasn’t happy he was leaving yeshivah, even if it was only for a few weeks.

The talmid asked for a brachah again and Rav Dovid said, “If it was my Velvel doing this, volt ich gehat groiss agmas nefesh — I would be very distressed.”

“I stood there overwhelmed,” recalls the talmid. “Was he comparing me to his son, a major talmid chacham, twice my age? That was his expectation from me? And I realized that yes! I was his talmid and that meant I was his son, with all the inherent expectations.”

Once a yungerman told Rav Dovid disapprovingly that some of the American bochurim were playing ball on Friday afternoons. Rav Dovid called in one of the American boys and asked if the bochurim dressed like bnei Torah and conducted themselves as bnei Torah when they went to play. After the talmid reassured the Rosh Yeshivah that this was the case, Rav Dovid told him it was fine.

A few months later, a visiting spiritual leader conducted a Shabbos in a small town outside of Jerusalem, and this talmid, eager for the experience, went to join. Rav Dovid heard about it and called him in. “You shouldn’t have left yeshivah for Shabbos,” he said first, and then he added, “uhn dos iz oich ah sport — this kind of experience is also a sport.”

A young American bochur arrived in yeshivah, having heard, like so many others, that by Rav Dovid Soloveitchik one can “see” yiras Shamayim.

While it was clear that the Rosh Yeshivah lived with an awareness of Heaven at every moment, the new talmid wasn’t sure what the expression “see yiras Shamayim” meant, until one particular day. It was shortly after the Rosh Yeshivah had made it clear that he expected every talmid to be perfectly on time for first seder, in their seats at nine o’clock sharp.

One of the bochurim arrived late, and to his misfortune, as he turned the corner to enter yeshivah, the Rosh Yeshivah was right in front of the building. Thinking quickly, he kept walking, as if he was not a talmid there. But Rav Dovid had seen him and recognized him, and he came into the yeshivah agitated by what had happened.

A bochur had come late, certainly a cause for distress, but the Rosh Yeshivah’s anguish seemed unnatural. “I don’t understand,” Rav Dovid exclaimed to another talmid, “if he comes later and I see him, he will be embarrassed for a moment and that’s it — but why isn’t he worried about the Ribono shel Olam? Why isn’t he worried about that embarrassment?”

“Then,” reflected the new talmid, “I realized what it means to ‘see’ yiras Shamayim.”

A close confidant of the Rosh Yeshivah took him to the ocean early one morning, and Rav Dovid went in to swim wearing a swimming yarmulke. “Is that a din?” the talmid asked. “Nein,” Rav Dovid conceded, “Ubber vi ken men gein uhn dem — how can one go without it?”

A talmid decided to join the yeshivah after hearing Rav Shlomo Wolbe say that he knew three genuine yirei Shamayim, and Rav Dovid was one of them. This talmid grew close to Rav Dovid, and eventually drove him to the levayah of Rav Refoel Soloveitchik.

Rav Dovid sat at his brother’s levayah, but he didn’t cry very much. Only once they were back in the car did Rav Dovid burst into bitter tears. The talmid understood. It was only here, where he was free of admiring glances, that Rav Dovid allowed himself to cry genuine tears.

Before Hashem, not before man.

Rav Dovid was a man of tradition; the ideas and values he spoke about remained as pure and pristine as when the yeshivah had started. Over the last few decades, the yeshivah grew again and again, eventually settling into a spacious building of its own, and the man of tradition brought children of a different world into his, never changing. He innovated only in the Torah he shared, the stream of chidushim growing wider and deeper. He allowed his Torah to be written and published by talmidim, and delivered different styles of shiur for different chaburos — at least one shiur daily, with special shiurim for veteran talmidim, and the weekly Chumash shiur as well.

But in a locked closet in his room sat the papers he had been working on for years, the chiddushim that he himself had written, the sefer that would only come out when he was no longer here — similar in format and style to Chiddushei Rabbeinu Chaim HaLevi and Chiddushei Rabbeinu Yitzchok Zev Halevi.

One imagines the sefer in print, the black cover and familiar font, and how in a few years from now, people will view Rav Dovid, the last surviving son of the Brisker Rav, as a name from the past, a different world.

But somehow, for all his old-world authenticity, he didn’t remain in the past. He was here with us until now, holding that torch without faltering or slipping, facing a world that changed and changed again and yet echoing the same message.

Truth endures. If you are true and you stand true, you don’t ever have to adapt.

He was a gift and his message was a gift.

At times, Rav Dovid — to whom storytelling wasn’t entertainment, but Torah itself — would recount the miracles of his family’s escape from Europe.

When the Second World War broke out in the summer of 1939, the Brisker Rav had been in the resort town of Krenitz for health reasons. The German invasion made it impossible for him to return home and for months, his worried family had no idea where he was.

After Succos, a letter from him finally reached Brisk. In it, the Rav instructed the Rebbetzin to send the older children to Vilna, where he had found refuge, while she should remain with the younger children at home.

At this point in the story Rav Dovid would speak slowly, describing the trip to Vilna, the panic and confusion they experienced along the way. But then they reached the city and a few bochurim directed them to the apartment where the Brisker Rav was staying.

“We were reunited with der Tatte,” he would recall and pause for a moment, allowing the emotion of that moment to wash over him. There would be much hardship ahead and much loss to face, but they were together.

They would be joined from that moment on, sharing a journey and a mission, bearing the sacred Torah of Brisk — the emes, the yiras Shamayim, and yes, the joy — and planting it on new soil.

Rav Meshulam Dovid HaLevi, with toil and truth, with perseverance and with much prayer, completed the journey. Now, as then, he has gone to join his father.

To be together again.

Together with der Tatte.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 847)

Oops! We could not locate your form.