War Room

Inside Rabbi Moshe Fhima’s operation to save Ukraine’s Jews

“Hello, Rabbi Fhima?”

The woman’s hesitancy was evident even to me, listening in by phone from 4,500 miles away.

“Which language do you speak?” the woman begins.

“Any language,” responds Rabbi Moshe Fhima, who, from his vantage point in Pinsk, Belarus, has taken a lead role in evacuating Jews from war-torn Ukraine. “Russian, Hebrew, Yiddish, English, Ukrainian,” he rattles off. “But best in Hebrew.”

The US has FEMA to handle disasters. The Jews in today’s Ukraine have Rabbi Fhima. British-born, Israeli-educated, and living right next door to the world’s largest refugee crisis since World War II, he has for 20 years been leading Yad Yisrael, the Karlin-Stolin organization for reviving Jewish life in Belarus and Ukraine.

Since Vladimir Putin’s forces rolled into neighboring Ukraine, he’s turned his Pinsk operation into a war room, channeling vast sums across borders to spirit away individuals and fragments of communities in a vast operation across the war zone.

I am on the phone with Rabbi Fhima for about a half hour, but our total talking time last no more than five minutes. He carries on simultaneous conversations with other people, one in English and another in Russian, before switching to a third in Hebrew. He ends each one with “Tishlach li b’WhatsApp,” peppered with “sekunda, sekunda, sekunda” — wait a second. That’s a universal language, I presume.

“You’re in Dnipro?” he screams into one of his phones. “I have a car coming from Kharkov and you need to give him $45,000! You hear me?”

He quickly hangs up to take another call, about a scheduled ambulance in Kyiv to evacuate a pregnant woman.

“So far,” Rabbi Fhima says in his firm but raspy tone, “everyone who wanted to get out until now has gotten out — bli ayin hara.”

Jews fleeing Ukraine can bring one suitcase each, leaving behind a lifetime of memories

Destination Belarus

Ukraine is currently convulsed by the world’s largest refugee crisis in 80 years, with 1.5 million of its citizens having fled in the week and a half since Russian president Vladimir Putin sent in his troops. An additional three million are expected to escape by the time Russia completes its invasion.

The three countries involved in this conflict — Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus — are the only former Soviet republics to have remained close allies after the Kremlin lowered the hammer-and-sickle flag in 1991. But Ukraine has drawn steadily closer to the west, angering Putin and leading to the current conflagration. Belarus, even though it has served as a staging ground for Russian troops, has become a destination of choice for Jews fleeing Ukraine, since it has the strongest community resources in the region.

Stories and images of Jews fleeing Ukraine are heartbreaking. Allowed one suitcase each, they have to choose from among a lifetime of memories to save, bumping against the realities of basic necessities such as clothes and food.

One man from Kyiv arrived in Monsey on Thursday with barely the shirt off his back. Just two weeks before he had been a prosperous businessman with 80 workers in his employ, a backbone of the local community, providing funds when needed. Now, he was just another refugee among many expected to pour into the United States in the days ahead.

“That’s the person in the best situation,” Rabbi Fhima says vehemently, “because he got out very quickly and he’s already in America.”

He and his team of about 15 people, made up mostly of members of the Karlin-Stolin community who had fled Kyiv, have helped more than a thousand people escape in the past week. Each major Ukrainian city — Kyiv, Kharkiv, Lviv, or Odessa, among others — has its own representative, and when a call comes in from someone from that city, the case is assigned to their representative.

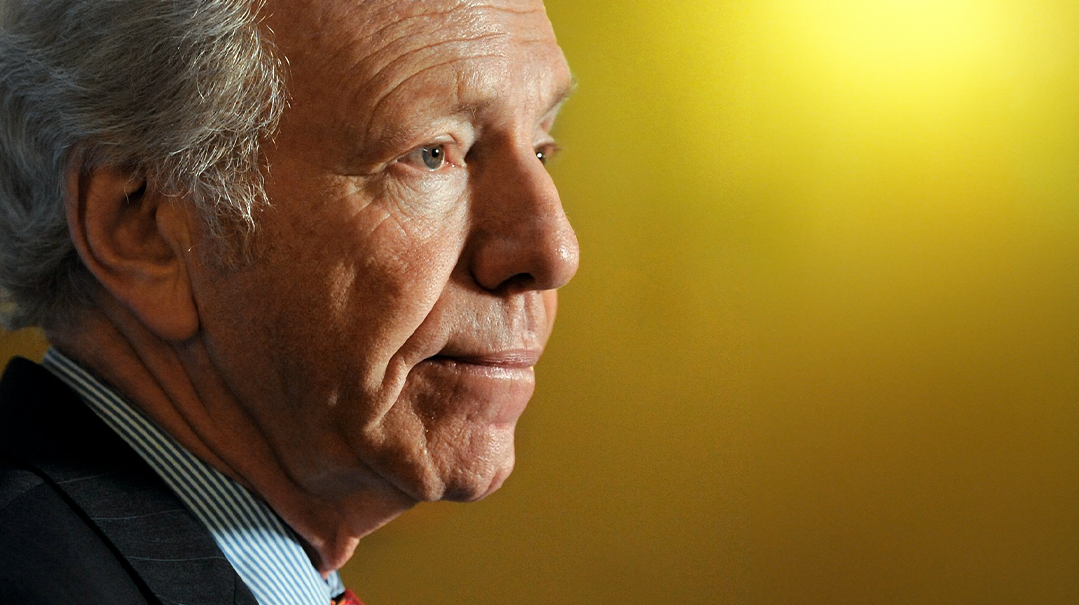

In a video update to supporters on Friday, Rabbi Fhima is the living portrait of an old-time askan — one hand holding a phone, the other holding a cigarette, from which he takes frequent puffs in the other, glasses perched on his yarmulke, and his tie hanging loosely around his neck over a white shirt.

Buying the Future

Rabbi Fhima estimates that he burns through $200,000 a day — “at a minimum.” He has been aided by a robust Jewish charity donation system, with millions of dollars raised to help save Ukraine’s estimated 45,000 Jews.

“The Jewish-Syrian community in America has taken responsibility for the rescue operation,” says Rabbi Fhima, who has made several Zoom pitches describing events from the ground, “and the Shema Yisrael organization has also helped with the expenses, and the United Jewish Appeal has promised us help. For now, kind people are lending us money. We promise to repay them, and we will, b’ezras Hashem.”

Cars to bus depots; the buses taking refugees to Lviv and the border; logistical expenses of food and board. With banks working sporadically, Rabbi Fhima works with cryptocurrencies, bitcoin in particular.

“The miracle is that while you can’t get dollars from the banks, there’s something called crypto, and that’s how we carry out these transactions,” Rabbi Fhima recounts. “So when we’re woken up at 4 a.m. by an urgent message that $100,000 is needed instantly, we’re able to transfer the entire sum without delay to Kyiv, and from there to the people working at the crossings. It’s the only financial system still functioning.”

Just that morning, he said, he had a group of refugees stranded near the border with no cash. “We met someone with cash, but he was a stranger — why should he trust us?” he said. “We transferred crypto directly to his wallet, and he gave us the money. And the group was able to continue.”

For the moment, he says, the money is going toward the rescue operation itself, but he emphasizes that for the refugees, the real difficulty begins after they’ve crossed the border.

“We’re talking about people who escaped over unpaved roads and weren’t allowed to bring anything with them,” Rabbi Fhima says. “They left all their belongings on the bus in Ukraine and came here with nothing but the clothes on their backs. We have to take care of their basic necessities.”

He received one call from a family stuck in Kharkiv, located in eastern Ukraine, the country’s second biggest city, which has seen entire neighborhoods leveled by Russian shelling. They pleaded with him to extricate them to safety.

“We hire car drivers to take them to a bus collection site in Kharkiv,” he says, describing the response. “This is the big expense — how much it costs depends on the mood of the driver, it could be $10,000, $15,000. We then take them by bus to Dnipro, then another bus takes them to Lviv, near Poland. People from other cities go directly to the border.”

Angels of Rescue

Yad Yisrael, founded by the Karlin-Stoliner Rebbe a couple of years before Communism collapsed and headed by Rabbi Shmuel Dishon and Rabbi Yaakov Shteierman, has emerged as a key angel of rescue during the current crisis, with three major centers are in Kyiv, Pinsk, and Lviv. Buses collect Jews across the breadth of the country, and transport them either to Lviv or across the Belarus border to Pinsk.

On the Rebbe’s recommendation, the group evacuated its main mosdos in Kyiv ten days before the war, transferring whatever they could to Mezhibuzh, which has an infrastructure for guests. Once the war started, the entire operation moved to Pinsk, whose Karlin neighborhood was the historical center of the kehillah until World War II. Karliner chassidim familiar with Pinsk have been assisting Rabbi Fhima in the operation.

“With their help,” he says, “we’ve been working nonstop since last Sunday to extract Jews from Ukraine. If someone calls today and asks to be evacuated, if the buses are ready in their city, and the bus isn’t full, then he gets into Belarus today. But normally he has to wait until the next morning.”

The wait averages between 15 and 29 hours. Moldova is a preferred crossing point is simply because border controls are easier to navigate there.

“The moment they reach the Moldovan side of the border, we take them temporarily to the capital Kishinev, where Rabbi Zalmanov of Chabad takes them in, and the next day we can start talking about the future,” Rabbi Fhima explains. “We send along with every bus a representative of ours, and then we take stock of their needs and where they want to continue. At this very moment, two more buses carrying 100 people set out, and four more are setting out from Kyiv, and there’s another bus leaving in an hour.”

Exactly as I surmised, Rabbi Fhima says he has three phones, and each member of his team is similarly equipped. But the skies over Belarus are overcast with rumors that the government in Minsk may join Russia’s battle, turning it into a war zone of its own.

“I don’t want to think about it,” says Rabbi Fhima just before hanging up. “We have somewhat of a plan if needed, but we’ll play it by ear.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 902)

Oops! We could not locate your form.