Unlocking A Family Secret

Jonathan Pollard and his fiancée, Rivka Abrahams Dunin, have more in common than meets the eye

Photos: Abrahams family archives

When a parent sits a child down and says, “I’ve got something important you need to know,” the child’s stomach begins to churn.

Rivka Abrahams Dunin was already a grown adult with children of her own when her father, Stephen Abrahams, dropped that line on her one day less than a decade ago, and Rivka still remembers the butterflies in her stomach.

Her father took her to Yad Vashem to view a folder of archived documents that her grandfather, Sergeant Karl Louis Abrahams, bequeathed to the world’s most famous Holocaust museum. Until his death in 1980, Sgt. Abrahams kept that folder in an olive-colored cabinet that he always kept locked. Rivka’s attention was often drawn to that cabinet, wondering what mysteries it might have held. At Yad Vashem, the contents of that cabinet, and her grandfather’s secrets, tumbled out before her very eyes.

The archives include photographs, documents, and a signed confession extracted from Rudolf Hoess, who masterminded the slaughter of more than 2.5 million people on his watch in Auschwitz.

Sgt. Abrahams was a key member of an elite British intelligence group — the 92 Field Security Section — that was in hot pursuit of Hoess in the winter of 1945-1946 after Hoess fled to evade capture. Sgt. Abrahams, an Orthodox Jew from Liverpool, was fluent in several languages, including German and French. His unit took on missions in Brussels, Paris, and Marseille before entering Germany near the end of World War II. Tracking down Hoess would be their toughest assignment.

“I was amazed to see that my grandfather provided Yad Vashem with all the information having to do with the capture,” Rivka said. “I was fortunate enough to have been given original handwritten letters that my grandfather had written to my grandmother after the arrest explaining how he felt. I was extremely proud of my grandfather, but at the same time, I knew I couldn’t keep quiet about what happened like he did. The Jewish People are family, and our whole family needs to know.”

Rivka, who became famous to the Jewish nation last week when she and Jonathan Pollard formally announced their engagement, was born in 1977 in Birmingham, England, into a Torah-observant family. She obtained a Jewish education in that area’s King David School. Since Birmingham had no Jewish high school, she attended a girls’ grammar school, which provided a higher level of secular education.

“That wasn’t for me, I didn’t like it at all,” she said.

So, at age 15, she enrolled in Carmel College in Oxford, which had a Lubavitch shaliach on campus. One Chanukah, the shaliach organized a trip to the US to the Chabad-Lubavitch World Headquarters at 770 Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights.

“From then onward, I felt like this was really for me,” Rivka said.

When she returned to England, she studied for one year at the Lubavitch House School in the Stamford Hill section of London and returned to Crown Heights for a year before moving to Israel to study at Machon Alte in Tzfas, but it was in Jerusalem where she would meet her bashert.

Shortly after the Six Day War, Chabad assigned Rabbi Moshe Weber z”l to be the shaliach at the Kosel to introduce the uninitiated into the mitzvah of donning tefillin. Rabbi Weber had a younger assistant, Yosef Eliyahu Dunin, for whom he made a shidduch with Rivka. Any man who went to the Kosel from 1998 to 2015 would have spotted Rabbi Dunin, his flowing red beard streaked with white, exhorting people to put on tefillin if they hadn’t done so that day.

One of Rabbi Dunin’s most famous “hauls” was an Italian priest who had come with a group, but broke away and confided in Rabbi Dunin that he had a Jewish mother. According to the obituary of Rabbi Dunin on COLlive, the “priest” returned a few months later, but this time in different garb. He was wearing a kippah, held his tallis and tefillin bag, and had come to live as a Jew in Eretz Yisrael.

“My husband was in touch with Jews all over the world,” Rivka recalls. “He was very much involved in being there for the soldiers that would come to the Kosel and had a great feeling of responsibility for them.”

Making a living was tough for the Dunins. They weren’t registered as a formal Chabad House, so they weren’t eligible for funding. “But Yosef would bring people home with him wherever we lived, so our home was always like an active Chabad House. It wasn’t easy financially, but spiritually, it was a very privileged shlichus.”

For the first three years of their marriage, the couple lived in Tel Tzion, and Rivka worked as a kindergarten teacher. The Dunins eventually moved to Pisgat Ze’ev. Over the years, they were blessed with seven children, whom Rivka had to raise singlehandedly when Yosef passed away at age 55 in 2015. Two of Rivka and Yosef’s daughters are married, and Rivka is now a proud grandmother of three. Her grandfather’s story has captivated her since she discovered his secret eight years ago, and now she sees it as her mission to share it with Am Yisrael.

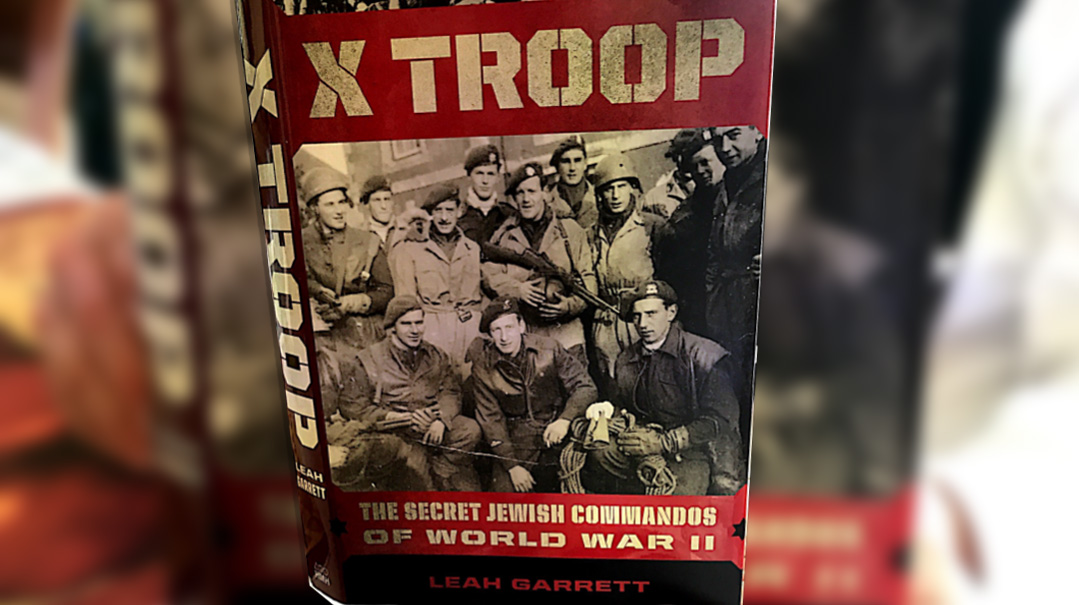

BEHIND ENEMY LINES A unit photo of the elite British intelligence group 92 Field Security Section. Sgt. Karl Louis Abrahams is in the front row, third from the right.

Sleepless Nights

The story of Rivka’s grandfather, nicknamed “Blitz” by his colleagues, has been written about only in passing on a few occasions.

An obituary on Sgt. Abrahams in the Jewish Chronicle of May 30, 1980, mentions nothing of his World War II service. The article quoted two fellow congregants at Liverpool’s Greenbank Drive Synagogue. One praised him for his service to the synagogue and for being “in the forefront of those who strove to uphold its traditions and the dignity and decorum of its services.” In the same vein, a second man eulogized Sgt. Abrahams, calling him “a man of quiet disposition, gentle and retiring in his manner, who shunned the limelight.”

Rivka recalls one family story from the 1960s to illustrate that point: “In 1968, someone from the British intelligence services came to my grandfather’s house and wanted to find out what he knew during World War II. From what I understand, my grandfather ‘played stupid,’ like he couldn’t recollect.”

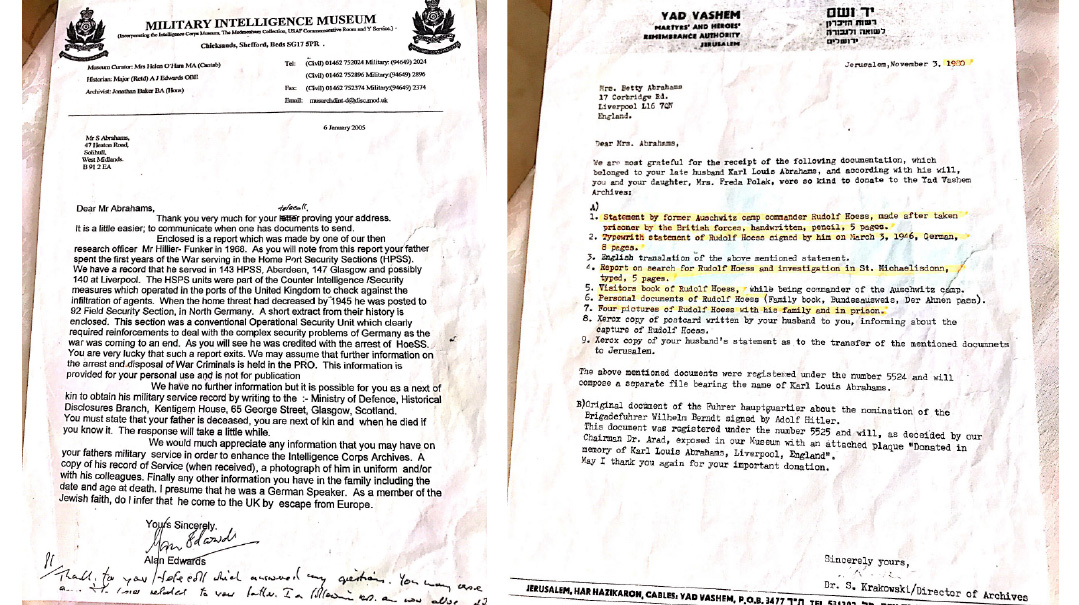

The British had organized dozens of field security units to operate behind enemy lines during the war. Sgt. Abrahams served in Unit 92. Among the documents Rivka showed me was a letter from British military intelligence to her father, Stephen Abrahams, dated January 6, 2005, crediting Sgt. Abrahams with the capture of Hoess. An accompanying document mentions the names of two other war criminals his unit captured, before adding: “However, their most important catch (by KL Abrahams), in a farmhouse near Flensburg was Rudolf Franz Hoess, the former second-in-command of Belsen and commandant of the so-called ‘quarantine camp’ of Oswiecim, better known as Auschwitz, in Poland.”

A second unit, the 270 Field Security Section, also claimed to have arrested Hoess. Another report, filed by Captain Victor Cross, who was head of Sgt. Abrahams’s unit, also references Field Security Section 318.

The accompanying document that British intelligence sent to the Abrahams family notes that more than one section was present in the area: “It seems likely this was a joint operation. At the time of writing the puzzle has not been resolved.”

The documentation Sgt. Abrahams willed to Yad Vashem includes a five-page handwritten statement in pencil from Rudolf Hoess following his capture; and an eight-page typewritten statement in German, signed by Hoess, along with an English translation.

Rivka says that documentation, plus her grandfather’s handwritten letters to her grandmother from that period, prove that her grandfather — and his unit — were the first to lay their hands on Hoess.

“What was so amazing, is that clearly from the personal letters, he was successful because he had the help of two wartime survivors who identified Hoess. One of them was someone he referred to as a ‘trustworthy soldier,’ who might have been Jewish,” Rivka said. “When it comes down to it, Hashem guided his footsteps, and was he fortunate enough to discover him.”

In two of the personal handwritten letters that Sgt. Abrahams wrote to his wife Betty, he describes the capture in couched language.

“The past few days have been crammed full of excitement and high-pressure work,” he writes. “After months of patient toil, we’ve made a big scoop about which you may read something in the newspapers fairly soon.”

Hoess was captured in March 1946, found hiding in a farmhouse in Flensburg, in north Germany, where he was living under the alias of Franz Lang, pretending to be a simple farmer.

After the capture, Abrahams writes his wife Betty again: “Hoess was the greatest swine that ever was, the most diabolical criminal in all human history. Henry [Roberts, a fellow soldier] and I worked on this case for five months, and it’s a great satisfaction to have got him at last. His interrogation was an experience I shall never forget.

“We were at it for almost three days and two nights on the trot. No sleep — the atmosphere was unreal as we heard him confessing that he personally supervised the gassing and burning of over two and a half million people, mostly our fellow Jews.”

TRUSTWORTHY SOLDIERS In identifying Rudolf Franz Hoess, the commandant of Auschwitz, Sgt. Abrahams (pictured here in the top row, third from the left), had the help of wartime survivors who may have been Jewish

Pollard Parses the Puzzle

The capture, interrogation, and confession of Hoess all took place between March 3 and March 15, 1946. There are some discrepancies in the dates between different documents, with Sgt. Abrahams referencing earlier dates for the arrest and some documents saying it happened a week or so later.

There is also some historical debate over whether Hoess’s wife gave the British the information that led to his capture, or whether Abrahams and his crew had already captured Hoess without help from his wife. One of the documents written by Captain Victor Cross, Abrahams’s supervising officer, mentions that the last time they had interrogated Hoess’s wife was the previous November, four months before they captured Hoess.

As I pored over the documents myself, Jonathan Pollard interjected and offered his analysis, suggesting it was quite likely the arrest took place earlier than reported and that Sgt. Abrahams kept Hoess “on ice” for a number of days before turning him over for processing by higher echelons.

“I can tell you from an operational intelligence standpoint,” Pollard tells Rivka, “that he wanted Hoess to sweat. I’m sure Hoess knew your grandfather was Jewish. That’s the worst nightmare a guy like Hoess could ever imagine. He’s being interrogated — not only by a British officer but by a Jew. He kept him on ice for any number of good reasons, to put pressure on him and keep him isolated.”

Pollard also contends that the skeptics who doubt that Hoess would have confessed so quickly don’t understand how the game is played.

“I’m speaking now from personal experience.” Pollard continued. “The person being interrogated is scared and disoriented and hasn’t got his story down. He is looking for any angle he can to befriend the interrogator, because he harbors the hope of being released or getting a break, so the first one who interrogates him gets the truth. A day, or two or three days later, the prisoner has time to come up with a story and gather his thoughts and organize his defense. Rivka’s grandfather was a consummate professional and knew exactly what was needed to get the truth out of Hoess.”

The British themselves had good reason to keep details about the capture of Hoess hidden, even though it was a big prize for them at the time.

Pollard noted that when Hoess was captured in 1946, the British Mandate still controlled Palestine. The pressure was building to carve a Jewish state out of the mandate after details of the Holocaust were coming out.

“The British would have been very reluctant to generate any sympathy for the survivors, out of concern there would be international pressure for them to be allowed to make aliyah,” Pollard said.

Although World War II had ended, the Cold War between the West and the Soviet Union was in its infancy. British, French, and American intelligence services were keen on recruiting high-ranking Nazi officers who could be useful to them in the conflict with the Soviets.

“I’m sure Rivka’s grandfather knew this,” Pollard said. “Trust me. As an intelligence officer, he was well aware of that track. So I think the reason Rivka’s grandfather kept the interrogation of Hoess a secret was that he considered it ‘insurance’ — in the event the British failed to prosecute him, a full confession of the monster would be available, and the British would then have no choice but to prosecute him. It was a smart, brave move by Rivka’s grandfather to ensure that justice for our people would ultimately be done.”

Ultimately, Hoess was tried and sentenced to death at the Nuremberg trials. He was hung on the gallows on April 16, 1947, in front of Auschwitz Gas Chamber #1.

IMPORTANT CATCH Two letters documenting Sgt. Abrahams’s role in the capture of Hoess: from the UK’s Military Intelligence Museum and from Yad Vashem. “You are very lucky that such a report exists”

Sweet Dreams

When Rivka reflects on her grandfather’s role, she finds it a bit of an anomaly, considering everything she ever heard about him.

“To think that he was able to capture one of the evilest of men — even the word devil is too nice of a word for Hoess — it didn’t fit his personality,” Rivka said. “I was only three years old when my grandfather passed away, but I do remember him.

“A child remembers who’s sweet and who’s scary. My grandfather was very sweet, with a warm smile. Even though I was so little at the time, I realized there was something very special about him. If I could, I would compare him to Yaakov Avinu, who wrestled with Eisav’s angel, and won.”

While Rivka’s memories of her grandfather are fleeting, she did tell me that he has appeared to her in some dreams.

“One was very super clear,” Rivka said. “It was Shabbos Parshas Zachor, seven years ago, when we read about the wiping out of Amalek. And after that dream, that’s when I started working on getting my grandfather’s story out.

“I could see him so clearly,” she continued. “He walked into our apartment. He sat down on the couch and he looked across at me and said, ‘You look like me.’

“I didn’t see any resemblance, but then he said he wanted to stay. It was a very clear dream. When I woke up, I looked at the couch I had seen him sitting on. I couldn’t bring myself to sit on that couch for a long time because it was so real to me. I never told this dream to my husband, Yosef, at the time, but about a month afterward I decided to tell him.

“Yosef asked me, ‘When did you have this dream?’ I told him it was on Friday night of parshas Zachor. He then told me that there had been many occasions when he’d woken up in the middle of the night after hearing footsteps and thought that somebody was in the apartment. That night of parshas Zachor was one of them, and he got out of bed to check the door. I got spiritual chills, because Yosef was so down-to-earth, for him to have said something like that was totally out of character.”

One month later, on the 4th of Iyar, Yosef passed away.

“I had to concentrate on raising the children and I couldn’t work on getting the story out,” Rivka said.

A New Beginning

Rivka’s younger children will soon have a stepfather in Jonathan Pollard. How he and Rivka met is a story of its own.

“I met Esther and Jonathan in the center of Jerusalem,” Rivka said.

Figuring she was with two people with riveting storylines of their own, she shared her grandfather’s story with them.

“Esther took this very seriously,” Rivka recalls. “We had just met on the street, but Esther had this genuine concern from the first time I met her, and she said yes, this is a story that has to get out, and she offered to connect me with contacts that she had.”

Rivka was impressed with Esther’s support and offer of help, despite her failing health. “I knew I had met someone super special. Jonathan is a gibor and she was a gibores.”

Rivka and Esther did meet on some other occasions. “The last time I saw her, I was the one who was very concerned, because she wasn’t looking well. I said, ‘Esther, please, be strong, we need you.’ ”

Esther passed away at the end of January, shortly after that final encounter, but according to Jonathan, Esther bequeathed Rivka to him.

“What I can say on the record is that Esther, of blessed memory, told me that she wanted me to be happy and that Rivka was a pure soul who would take care of me. She kept telling me this, up until the end of her life. When Rivka and I decided to marry, we went to Esther’s kever and thanked her for the shidduch she performed. It was an incredibly emotional moment for both of us.”

It couldn’t have come at a better time, for both Jonathan and Rivka. We have now entered a new year, with new beginnings for all of us, may they be sweet.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 929)

Oops! We could not locate your form.