Ukraine War Exposes Biden Foreign Policy Flaws

Biden spurned Saudis, now it's payback time

Joe Biden’s idealistic foreign policy, which sought to make human rights the primary consideration in America’s international affairs, seems to have run aground, just as Russia’s Vladimir Putin is committing the most egregious violation of civic order in Europe since the end of the Cold War. Some staunch US allies are left feeling taken for granted, and that they can’t trust Washington not to zigzag at key moments.

“The Biden White House has picked sides when it comes to our allies and our adversaries, and… let’s put it this way, our allies are perplexed, and our adversaries are pleased,” says Michael Pregent, senior fellow at the Hudson Institute.

When Biden entered office last January, the mission he undertook in foreign policy was immediately decried by many analysts as impossible. Theorists have debated for centuries on whether considerations of morality should be the basis of a state’s foreign-policy decisions.

The reality, of course, is complex, and depends largely on circumstances. A small, poor country may not carry any weight in America’s foreign relations, but what about a strong, prosperous country? Historically, the conventional wisdom has held that interests outweigh values. That is, every democratic country ideally aspires to distance itself from autocratic regimes. But when the ideal comes into conflict with national interest — be it security, energy, or trade —interest usually wins out.

But Biden insisted during his campaign that all this would change under his administration, and primacy would be given to human rights in all foreign policy decisions. So, for example, the State Department decided in a rare move to withhold part of its aid to Egypt due to the country’s human rights violations. The fact that Egypt is a key American ally in the Middle East made no difference.

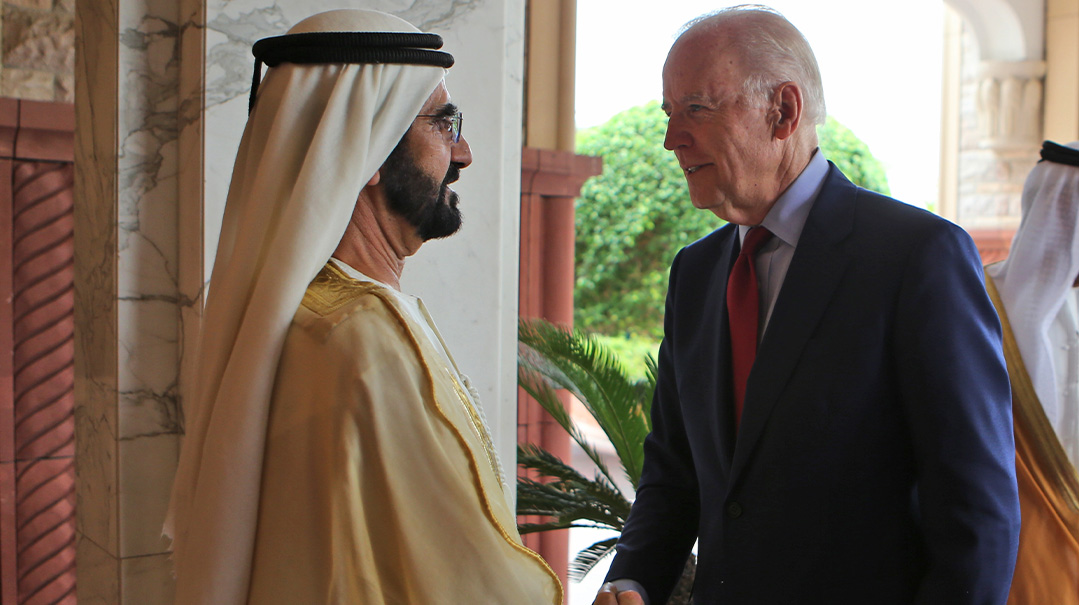

Another country whose relations with Washington have suffered under Biden is Saudi Arabia. Since entering office, Biden has kept his distance from Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), due to his implication in the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. When queried on this subject, the White House has evaded the issue with the protocol excuse, pointing out that King Salman, MBS’s father, is still alive. This is a pretty flimsy excuse, given how clear it is to everyone that bin Salman is the one really in charge.

Relations between the two countries have been tense for the past year, and the United States’ eagerness to sign a nuclear deal with Iran hasn’t helped matters one bit. Ten days ago, Mohammed bin Salman sat for an interview with the Atlantic in which he made abundantly clear what he thinks about Washington’s icy treatment.

“Simply, I do not care,” he replied, when asked whether Biden misunderstands something about him. Alienating the Saudi monarchy, he suggested, would harm Biden’s position. “It’s up to him to think about the interests of America.”

But last week something changed. The sharp spike in oil prices resulting from the war in Ukraine led Biden to make a perfect U-turn and phone bin Salman. According to a report in the Wall Street Journal — denied by the White House — bin Salman declined the call. In addition, Riyadh refused an American request to step up oil production, a move that would have angered Russia.

Saudi Arabia is a longstanding American ally, and it’s no secret that oil is key part to the relationship. But have the Saudis reached a point where they care more about what the Kremlin thinks than the White House? And if so, what does this say about the future of the Middle East?

“The Biden team has abandoned our allies and their positions when it comes to threats from Iran and its proxies,” says the Hudson Institute’s Michael Pregent.

The Biden administration should not be surprised that key allies, including Israel, abstained from condemning the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Pregent says, and that they are now “snubbing a president who has demonized Saudi Arabia, left allies to suffer Houthi rocket and missile attacks, and has dismissed their concerns about Iran’s nuclear aspirations.”

And Biden should only expect continued iciness, Pregent says. “Our allies know that for the next two and half years, the US will not stand with them against threats to their national security,” he tells Mishpacha. “Our allies are now hedging their positions and looking to Russia and China to provide weapon systems and do what the US won’t — be pragmatic and consistent.”

“This was very predictable,” says Jonathan Schanzer, senior vice president at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD) in Washington. “The White House spurned Saudi Arabia while it demonstrated less interest in the UAE during Biden’s first year in office. It is not surprising that these two governments would not jump at an opportunity to help the administration amidst an energy crisis.

“These calls were made out of desperation,” Schanzer says. “Right now, the White House policy is a reactionary one. It is swinging wildly from crisis to crisis.”

Asked if the refusal of MBS (and the UAE’s Mohammed bin Zayed) to take calls from Biden had to do with Iran deal talks, Schanzer says: “The Vienna negotiations are likely a significant element. But bilateral ties are under strain regardless. Particularly, Saudi Arabia has been spurned by this administration. The Gulf states are undeniably hedging right now. And not just with Russia. China, too. Much hinges right now on the American response to the Ukraine crisis. If the US allows Ukraine to fall, many weaker countries in the Middle East and beyond will openly question the value of their alliance with Washington.”

Dan Arbell, a scholar-in-residence at American University and 25-year diplomat who previously served as deputy chief of mission at Israel’s embassy in Washington, takes a softer view of Biden’s apparent change in course.

“The Ukraine crisis, the rise in oil prices, and Europe’s energy shortage all warranted a different approach by the administration, in an attempt to convince the Saudis to agree to increase their oil production to help stabilize the world energy market,” Arbell says. “The administration is not abandoning its human rights agenda, but it can be put on the back-burner until the Russia-Ukraine crisis is resolved.”

He adds that administration critics need to take their eyes off Iran and understand what is really driving the oil kingdoms’ frostiness.

“The Iran nuclear issue may partly explain the Saudi refusal, but it’s not the only reason,” he said. “As the US is seen as pivoting from the Middle East, Russia has made inroads into the Gulf. At present, all GCC states have good relations with Moscow. It doesn’t mean they’ll choose Russia over the US, but they are playing both sides.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 903)

Oops! We could not locate your form.