Twists, Turns, and Truth

The Sklare Family saga inverted the Jewish American dream

Photos: Eli Greengart, family archives

The general trajectory of American Jewry is well-known: an immigrant first generation, which in many cases held on to the kashrus and Shabbos observance of their birthplaces; a second generation with warm memories of their parents’ religious rituals but a dominant focus on achieving financial and social success; and then a third generation with no strong memories of observant bubbes and zeides, and pitifully insufficient connection to the Jewish community or tradition to provide a buffer against the twin sirens of assimilation and intermarriage.

Ironically, the story of the Sklare family takes the opposite trajectory. It begins with Marshall Sklare, a leading scholar and famed chronicler of the Conservative movement in America, continues with his son — who as a young teen sought out great Jews like Rav Aryeh Levin and the Steipler Gaon to guide him into the world of Torah — and flourishes today with a third generation of maggidei shiur and marbitzei Torah.

Though Marshall Sklare and his wife initially resisted their son’s move to fervent Orthodox observance, in time he came to take pride in the path his son had chosen and rejoiced that his descendants would not be among those lost to the Jewish people, like the children of so many of the Jews he studied. And they, in turn, recognize that his abiding love of the Jewish people and courage in telling unpopular truths planted the seeds of the family’s return to tradition.

Marshall Sklare was one of the first to sound the alarm on the threat of intermarriage

The Courage of His Convictions

Marshall Sklare

M

arshall Sklare (b. 1921) came from a family of business people. From them he absorbed a strong work ethic and commitment to giving tzedakah. But from an early age, he also showed an intellectual bent, combined with a deep attraction to Jewish life. He affiliated Conservative, like his parents — but he was likely influenced by his father’s Orthodox parents. (His immigrant grandmother resisted all acculturation so fiercely that after 50 years in America, she spoke less than 100 words of English.)

Even as a high school student and throughout college at Northwestern University, Marshall Sklare took courses at Chicago’s College of Jewish Studies (today the Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies). One of his teachers there, Fritz Bamberger, an émigré historian from Germany, was so impressed by his student’s eagerness to learn Jewish history that he undertook to teach with him privately, without recompense.

For his doctoral thesis at Columbia University, Sklare chose to write about Conservative Judaism in the United States. He worried that he could not be sufficiently objective about a movement in which he was raised. But he need not have feared. A prominent Conservative rabbi is said to have told him after the publication of the thesis as Conservative Judaism: An American Religious Movement by the Free Press in 1955, “Young man, who told you to write the truth about the Conservative movement?” For he had exposed both the movement’s lack of a coherent theology, and the lack of interest in such on the part of the laity, who controlled the synagogues. (See this week’s “Outlook” column for a fuller treatment.)

At the time, a plurality of American Jews was affiliated with the Conservative movement, and it was the fastest growing segment of American Jewry, particularly in suburban areas. Unlike the Reform movement, the Conservative movement never formally declared its break with halachah, though among the laity, few could be described as observant.

Marshall Sklare’s Conservative Judaism was widely hailed, and has been republished many times, most recently in 2012, 20 years after his passing. It is a masterpiece of narrative sociology presented without academic jargon.

In Sklare’s telling, the American movement was formed almost entirely of second-generation American Jews of Eastern European backgrounds, who were put off by the Reform movement’s coldness and complete break with tradition. They did not want the strict mitzvah observance of their Orthodox ancestors — but they still hoped to retain a taste of their childhood traditions.

But that sentimental attachment to “tradition” sans firm fealty to halachah could not be passed on and has proven unsustainable. Since at least the early 1990s, the movement has suffered an implosion of membership. Sklare’s warnings proved prescient; he correctly identified the movement’s vulnerabilities and predicted its downward turn.

Warning Signs

In 1952, his doctorate successfully completed, Sklare went to work for the American Jewish Committee as director of research. His office was adjacent to that of renowned Holocaust historian Lucy Dawidowicz and Milton Himmelfarb, who, along with his brother-in-law Irving Kristol and Norman Podhoretz, the editor of Commentary Magazine, was one of the founding fathers of the neo-conservative movement. A joke at the time ran: Marshall Sklare knows everything about American Jewry; Lucy Dawidowicz knows everything about Eastern European Jewry; and Milton Himmelfarb knows everything else.

Sklare’s research while at the AJC resulted in a second book, Jewish Identity on the suburban frontier: A study of group survival in the open society, which Harvard sociologist Nathan Glazer predicted would be “the starting point for all serious study of American Judaism for a long time.” (The affluent Midwestern suburban community upon which the study was based was referenced as “Lakeville” in order to maintain the participants’ privacy. Based on Sklare’s description of one Conservative synagogue and four Reform temples, one of which was anti-Zionist, and a Chabad that successfully established a major presence in the downtown business district in the ’80s, “Lakeville” is almost certainly the Chicago suburb of Highland Park, which borders Lake Michigan and in which I grew up.)

Based on results of the Lakeville study, Marshall Sklare wrote a series of articles in Commentary questioning the easy assumption undergirding Conservative Jewry: that full participation in an open society poses no danger to Jewish identity.

Among the indicators of dramatic weakening of Jewish identity revealed by his study, was a questionnaire on what Lakeville’s Jews saw as central to being a “good Jew.” Kashrus and Shabbos observance ranked at the bottom, and “helping Negroes” at the top.

Sklare was one of the first to sound the alarm on the threat of intermarriage in an April, 1964 Commentary article, “Intermarriage and the Jewish Future.” Jewish survival, he argued, is no longer threatened “by Gentile hostility but by Jewish indifference.”

Six years later, he returned to the subject of intermarriage in a more ominously entitled Commentary piece, “Intermarriage and Jewish Survival.” Some of the basic beliefs of American Jews — romantic love trumps all and the equality of all people — left Jewish parents with little to offer their children against intermarriage.

All Marshall Sklare’s powers of incisive analysis and his deeply traditionalist and conservative personal leanings came to the fore in a lengthy critique of a wildly popular book called The Jewish Catalog: A Do-It Yourself Kit (1973). By the time his essay appeared, the book was already a publishing phenomenon, having sold 95,000 copies, second only to the Hebrew Bible in publications of the Jewish Publication Society. Despite its resolutely contemptuous attitude to the Jewish establishment, that same establishment rapturously greeted the work, as a long-awaited sign that there was yet life and Jewish interest among the youth.

Sklare was considerably less excited, as his essay “The Greening of Judaism” made clear. Though the authors of The Jewish Catalog demonstrated a genuine familiarity with Jewish sources and practice, that knowledge had been “put at the service of the latest cultural and aesthetic fads,” he wrote, “with results that are funny, vulgar, charming, and meretricious all at once.”

Among the meretricious elements was the authors’ cavalier attitude to halachah. “The halachah is there to inform and set guidelines, to raise questions, to offer solutions, to provide inspiration — but not to dictate behavior,” wrote the editors. They found in the ancient texts mysteries “which are timeless and powerfully evocative — elements which are missing from contemporary life,” but, Sklare pointed out, “exempt themselves from the central feature of Jewish religious law — its normativeness.”

As an example, The Jewish Catalog contained a long section on how to bake matzos at home, though the authors surely knew that no home oven reaches the requisite heat, and thus “the unleavened bread prepared in the home according to the Catalog’s instructions would in fact be leavened bread in the eyes of Jewish law.”

“G-d does not figure largely in these pages,” Sklare wrote. “There is a great deal of material on the accoutrements of prayer,” for example, an entire chapter on candle making — “but significantly less on prayer itself.”

What about Halachah?

Though his sons chose a different trajectory, they would say that Marshall laid the path for them. He kept a strictly kosher home, always walked to synagogue, and took the arba minim on Succos. In the words of his son Joshua, who followed his older brother into the Orthodox world, his father not only possessed “an overwhelming ahavas Yisrael, but a passionate love of being Jewish.”

As he once emphasized to a group of Jewish educators, if they wanted to instill Jewish identity in their students and a defense against intermarriage, they would have to answer the question: “What do you stand for when you remain separate?”

Most important, he never dreamed that what he termed in one essay “the ever-dying people” could survive without a commitment to halachah: “There cannot be an authentic Jewish people without the continuity of the Jewish tradition, even as there cannot be meaningful continuity of Jewish tradition without the maintenance of the Jewish group.”

At a conference on intermarriage organized by Brandeis’s Center for Modern Jewish Studies, which he founded as the first academic center to focus on Jewish life in America, a number of presenters argued that intermarriage offered the potential to expand the Jewish community. He dispensed that argument with three words written in bold on one such paper: What about halachah!

A Premature Elegy for Orthodoxy

When Conservative Judaism was published in 1955, Sklare saw no future for a major revival of Orthodox Jewry in America: He described Orthodoxy as a “case study of institutional decay.” In that judgment he was joined by a number of graduates of Orthodox yeshivos who left for the Conservative rabbinate in the late 1940s and early ’50s.

By the time Conservative Judaism was republished in 1972, however, he had sharply revised that judgment, and described Orthodoxy as having “refused to accept the role of invalid.”

What would he write were he alive today to see the decline of the Conservative movement — and his own descendants living vibrant Orthodox lives?

The Teen Who Turned the Family Tide

Daniel Sklare

D

aniel Sklare, Marshall’s oldest son, is the middle generation of our three-generational Sklare family saga. Unlike his father, one of America’s leading public intellectuals, he is not a public figure. Nor has he attained fame as a teacher of Torah, like his son Rabbi Yonah Sklare.

After completing his doctorate in audiology, he worked as both a clinical and research audiologist, including with NASA on space missions. But most of his career, prior to his retirement in 2015, was spent in the National Institutes of Health, in the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, guiding new research scientists in the grant writing process.

Yet Daniel, now 71, is unmistakably the hero of the Sklare family history, the fulcrum upon which the family story turns. Yehoshua Sklare, his younger brother by eight years, describes him as someone for whom he feels “admiration bordering on awe.”

Daniel inherited his father’s seriousness and imbibed his “love of being Jewish.” But he was determined from an early age to express that love in his own way.

When Rav Aryeh Levin Sobbed

For the academic year 1965-66 — Daniel’s bar mitzvah year — Marshall Sklare was awarded a Fulbright professorship at the Hebrew University. The Sklare family rented an apartment in Jerusalem’s Nayot neighborhood, and Daniel, who had learned Ivrit back in America, was enrolled in the local public school. But after a few instances of what he considered the disparagement of Torah, he insisted that his parents move him to a religious school, albeit one that was coed.

“I was a rebellious, headstrong teenager, a man on a mission,” Reb Daniel says of that stage of his life. “I felt an incredible push to prepare for a life of Torah, and I began searching for those who could help me do so.”

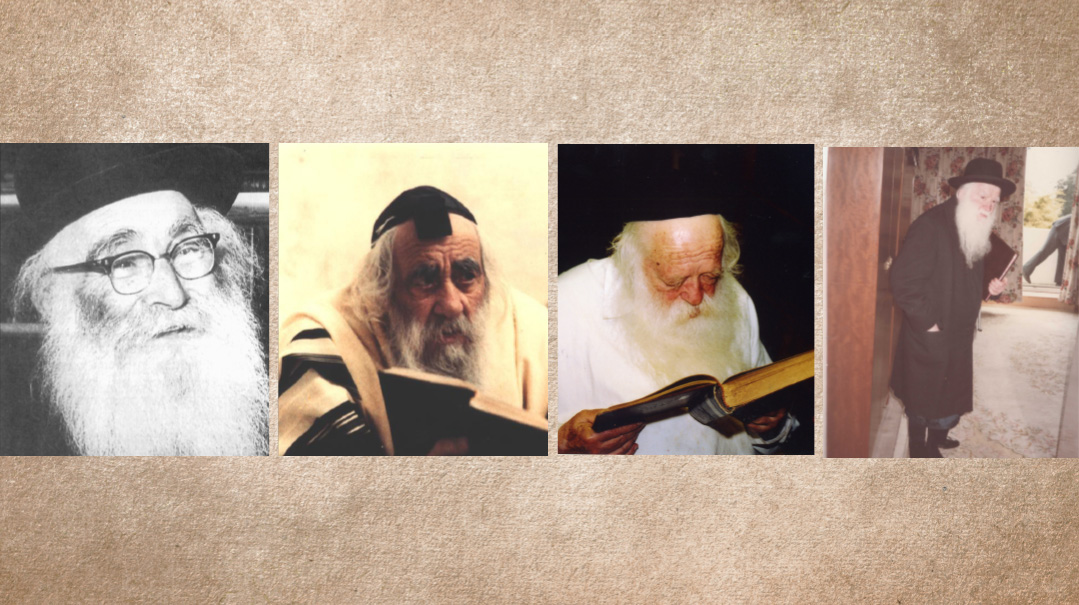

The first mentor he sought out was Rav Aryeh Levin, the famous “tzaddik in our time.” Daniel found him in the Zoharei Chama shul near the legendary Eitz Chaim cheder and yeshivah, where he served as a mashgiach to the younger boys.

“Rav Aryeh was the embodiment of the Torah’s description of Yehoshua, ish asher ruach bo, someone who could deal with each person at his level,” Daniel remembers. “Even though I was barely bar mitzvah age, he gave me all the kavod in the world, even addressing me, initially, in the third person.”

Rav Aryeh had just lost his wife, and was then living with his son Refoel in the Mishkenot neighborhood, just outside the walls of the Old City. He learned with Daniel once a week — either halachah, or parshah, or an idea in machshavah that he wanted to share — and they would also go for a walk when his frail health permitted.

“I’ll never forget the time we came across a discarded refrigerator in a poor neighborhood,” Daniel says. “Rav Aryeh started sobbing uncontrollably. I just stood their holding his arm, completely at a loss.

“Eventually, he calmed down a bit, and explained that for one of the poor families in that neighborhood to throw out a refrigerator, it would have had to be completely irreparable — a severe financial blow to a very poor family. He cited a Gemara in Chullin (77b), which describes the efforts of the chachamim to heal a diseased fruit tree, upon which a poor family’s sustenance depended.”

Another time, Rav Aryeh sent Daniel as his personal emissary to the bar mitzvah of boy from a Moroccan family who lived in a very run-down neighborhood. “He instructed me to wear my best suit and to be sure to take my American passport,” Daniel says. “He knew that a guest from the United States would convey great honor to the bar mitzvah boy.”

“I was a rebellious, headstrong teenager, a man on a mission” – Daniel Sklare

At Rav Chaim Kanievsky’s Table

Rav Aryeh also recommended that the young seeker make the acquaintance of some of Yerushalayim’s hidden tzaddikim, who would gather to recite Tikkun Chatzos, and then go for a walk together before resuming their learning. Rav Aryeh instructed Daniel to go to the mikveh before meeting such great men and to remain silent in their presence. “You are there to absorb,” he said.

“Because the group often included one or two Sephardic chachamim — the Beis Yisrael of Gur was another sometime participant, along with Rav Eliyahu Roth and Rav Moshe Weber — the conversation was in Lashon Hakodesh,” Daniel says, “though for the most part their walks were conducted in silence. Even at my young age, the spiritual elevation of this group was palpable.”

His next stop, arranged by Rav Aryeh, whose granddaughter Batsheva Elyashiv had married Rav Chaim Kanievsky, was the home of the Steipler Gaon in Bnei Brak.

“He saw that I was drawing closer and closer to Torah, and that the year in Israel would be my best chance,” is Reb Daniel’s explanation of the time the Steipler gave him, during his seven or so visits to the latter’s home. Though the Steipler’s severe hearing loss made communication difficult, the Steipler showed him great warmth and gave him a blessing that he would produce sons who would light up the world with their Torah.

The Steipler also arranged for Daniel to meet with his son Rav Chaim Kanievsky a number of times. Daniel would go to Reb Chaim’s home before he returned from Kollel Chazon Ish at midday and helped Rebbetzin Kanievsky set the table and serve Reb Chaim when he returned.

What struck the young guest most about Reb Chaim was his menuchas hanefesh. “He did not let the world outside penetrate his consciousness enough to disturb him in any way,” Daniel remembers. “For instance, it was clear that he had no idea what he was eating.”

Instead, he focused on the conversation. “I would read a few s’ifim of Kitzur Shulchan Aruch, and Reb Chaim would trace the development of the halachah under discussion from the Mishnah to the Gemara, to the Rishonim, and on to the Rambam and Shulchan Aruch — all in their precise language.

“I, of course, could follow only a little of this, but I think the Steipler felt that the exercise would be relaxing for Reb Chaim, and for me, it would provide a concrete example of what a person can achieve in Torah learning.”

Daniel Sklare was just bar mitzvah age when he was advised to seek out many teachers. Rav Aryeh Levin sent him to meet the Steipler, who introduced him to a young Rav Chaim Kanievsky. Later, he formed a close relationship with Rav Yehuda Zev Segal as well

“Draw from Many Teachers”

During the time they spent together, the Steipler gave Daniel specific guidance about what and how to learn. “I think that the Steipler foresaw that I would not have an easy entrance into the world of Torah and guided me accordingly,” Daniel muses. “Since I would be, at least in part, self-educated, he told me to learn the seforim of the Piaseczna Rebbe, Rav Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, particularly his Chovos Hatalmidim.

“The Piaseczna emphasizes the necessity of the talmid being an active participant in his own self-development, and of necessity that was true for me. I think he also felt that the fire of Polish chassidus found in the Piaseczna’s works, with a strong emphasis on the joy of a relationship to Hashem, was well-suited to my intense nature.”

The Steipler also told Daniel not to become a baal shittah, tied to one specific approach, but rather to draw widely from many teachers. Interestingly, many years later he had an almost hour-long yechidus with the Lubavitcher Rebbe, who gave Daniel similar advice. “At the end of our meeting, he handed me a list of outstanding Torah personalities across a wide Torah spectrum, and told me to seek each of them out and extract what I could from their approach.”

The Steipler was known for his psychological acuity. (A new work, Guiding with Wisdom, has just been published based on the Steipler’s letters to the late Torah psychologist Rabbi Yaakov Greenwald.) He gave Daniel much guidance before his return to the United States.

“He told me that I should avoid confrontation with my parents over such issues as to whether to attend a Mizrachi-affiliated high school. But when it came to mitzvah observance, I was not obligated by my parents’ standards of observance.”

Was the guidance effective?

“In terms of avoiding confrontation, I was only partially successful,” Daniel concedes. “There were some fierce battles. But his advice about choosing a school proved prescient: I was not accepted into the two black-hat yeshivos in Brooklyn to which I applied. Given my family background, perhaps they suspected that I might be some kind of spy.”

At that point Daniel and his parents compromised on the Yeshiva of Flatbush, an Orthodox albeit coed high school.

His ninth-grade Gemara rebbe (the Gemara shiur was all male), Rabbi Yechezkel Lichtman, was an early talmid of Rav Aharon Kotler in Lakewood, and would go on to serve as a rosh yeshivah in Hebrew Theological College (Skokie Yeshiva). He introduced Daniel to yeshivah lomdus through the classical work Shev Shmayasa, and broadened his horizons in Jewish thought through the Beis Elokim of the Mabit.

Subsequently, in the yeshivah program at Yeshiva University, his primary Gemara rebbe was Rav Shimon Romm, a talmid of Novardok Yeshiva and of Rav Aharon Kotler in Kletzk, before joining the Mirrer Yeshiva, where he received semichah from Rav Avraham Tzvi Hirsch Kamai Hy”d, the last rav of Mir, as well as the rosh yeshivah.

While in graduate school at NYU, Reb Daniel became attached to the Breuer’s community of Washington Heights. In the mid-70s, he was employed by the community to teach the influx of Russian Jewish youngsters whom the community sought to integrate, and became close to both Rav Yosef Breuer and the head of the Kehillas Adas Yeshurun beis din, Rav Shimon Schwab.

“One of my strongest memories of Washington Heights community is of Leil Shabbos meals with Rav Breuer,” he remembers. “The Rav would deliver a lengthy and complicated derashah at the table in German, and had his son translate so I could follow.”

While in shidduchim, he asked Rav Schwab whether there might be a problem meeting a young woman with a name similar but not identical to his mother’s. Rav Schwab told him there would not, and pulled out a sefer and opened to the exact page that addressed the issue. “When you become a posek, you receive an extra measure of siyata d’Shmaya,” Rav Schwab commented.

To Listen and Absorb

Over the years, Daniel has always heeded the advice of the Steipler Gaon to draw upon a wide range of Torah personalities. One of those was the Manchester Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Yehudah Zev Segal. He relates an interesting bit of tochachah he once received from Rav Segal.

“In 1990, I received a visit from a State Department official, who told me that Kuwait wanted to build an audiology clinic in Kuwait City. Would I be interested in overseeing the development of the clinic? The Kuwaitis had already investigated me, and took pains to assure me that my kashrus needs would be fully taken care of.

“But our kids were still young, and I felt that I had too little time with them as it was, between my daily commute back and forth from Baltimore to Washington D.C. and not infrequent travels around the country in connection with my job. So I turned down the offer.

“When I subsequently told the Manchester Rosh Yeshivah about the offer, his response was uncharacteristically sharp. ‘Why didn’t you at least ask a sh’eilah?’ he challenged me. ‘The king of Kuwait still holds the power of life and death over his subjects, and you could have recited the blessing, she’chalak m’kvodo l’basar ve’dam. Chazal teach us the malchusa d’ara — the earthly kingdom, resembles the Heavenly kingdom. Just think of the yiras Shamayim you could have experienced!’ ”

Daniel Sklare listened and absorbed, just has he has learned from the entire range of Torah figures he has sought out over the nearly six decades since his single transformative year in Jerusalem.

“If I have learned anything from observing my brother all these years,” writes his younger brother Yehoshua, “it is that if one possesses sufficient will and puts forth maximum effort, one can carve a moral and ethical oasis for oneself, both in the workplace and in the home, that can counteract some of the negative elements of contemporary society.”

Pulling All the Threads Together

Rabbi Yonah Sklare

T

here are no stories of teenage rebellion, at least not of the type worthy of preservation for posterity, between the second and third generations of the Sklare family. The six children — four daughters and two sons — of Daniel and Yehudis Sklare are all products of the normative chareidi world. The four girls all married bnei Torah, three of whom are professionals, and one of whom, Rabbi Yossi Rosenfeld, is the mazkir of the Baltimore beis din and a respected posek in his own right.

The two sons, Zev and Yonah, were both destined for success in the yeshivah world. As Rav Ezra Neuberger, Rosh Kollel of Ner Israel, puts it, “Brilliance is not in short supply in the Sklare family.” Rabbi Zev Sklare, the older brother, is a maggid shiur in the beis medrash program of the Yeshiva of Minneapolis, and Rabbi Yonah Sklare, upon whom we shall be focusing, is a prolific marbitz Torah in Baltimore.

There are, of course, differences between the generations. Daniel Sklare is soft-spoken; his son Yonah exuberant. In a Zoom conversation between us, Reb Yonah teases his father for being risk adverse; he is, by contrast, a promoter of “out-of-the-box” thinking and panoramic visions.

Reb Daniel’s pride in his son is evident: “We used to learn together once a week, but when I realized the kind of schedule he keeps, I could not take up any of his scarce time.”

Because the Sklare children were raised in a secure Torah home, they had no need to distance themselves from their Sklare grandparents. “My father had to fight the battles he did: I did not have to fight any such battles, which has allowed me to embrace my ancestors,” says Reb Yonah. Reb Daniel tells me that he never read his father’s major works; Reb Yonah has. When I effusively praise Marshall Sklare’s incisive intellect to Reb Yonah, after reading his Commentary article “The Greening of American Jewry,” he is delighted.

Marshall Sklare is to him “Grandpa,” or “k’vod zikni,” not just “my grandfather.” He relates a story from Marshall Sklare’s first years at Brandeis with deep admiration. “During the student riots of the late ’60s, a group of black students entered the kosher dining room with the intention of rendering the kitchen treif. He planted himself in the doorway to the kitchen and told the intruders they would have to throw him aside to get into the kitchen. They left and never returned.”

Reb Yonah doesn’t judge his grandparents at all. “They were born into a very different America than I was, and without any of the opportunities for Torah learning with which I grew up.”

Far from being embarrassed about ancestors who were not fully shomer Torah u’mitzvos, Reb Yonah feels a deep neshamah-connection to his grandparents, and appreciates the many ways he was privileged to be descended from them. He attributes his simchas hachayim largely to his maternal grandmother, Rose Sklare, whom he knew well into adulthood. And his passion for teaching could well have been inherited from his grandfather.

Moreover, he feels that his background has also been an advantage in many respects. “Children of baalei teshuvah,” he comments, “would have been a fitting subject for my grandfather’s next sociological study.

“My wide-ranging interests — history, psychology, and sociology — make it possible for me to draw close a more diverse spectrum of Jews than some more conventional talmidei chachamim might be able to reach,” Reb Yonah observes. And indeed his daily schedule is remarkable not only for breadth of the Torah he teaches but for the number of different types of groups to whom he is teaching.

As Many Shiurim as He Can Give

Reb Yonah’s rosh kollel responsibilities begin at 5:50 a.m. with a chaburah of bnei Torah, many of them serious talmidei chachamim, for whom Reb Yonah prepares ma’arei mekomos and gives a weekly shiur — currently in Yoma. That is followed by a another chaburah for self-employed balabatim in the shul of Rabbi Yissachar Dov Eichentstein, a scion of the Ziditchover chassidic dynasty. The chaburah explores topics in halachah — at present kibbud av v’eim — from the Gemara to contemporary poskim. Rabbi Sklare prepares pamphlets of the material and gives a weekly shiur. And at night, he heads a two-hour night seder in Beis Medrash Minchas Yitzchak for ambitious avreichim eager to learn a second seder b’iyun — currently tractate Mikvaos.

Besides daily chaburos focused on Shas and poskim, Reb Yonah gives a weekly advanced class in Tanach at Maalot Seminary; a weekly Chumash shiur by Zoom, and another one on Thursday night, after the kollel. Once or twice a month, he delivers machshavah derashos in the Ner Israel Kollel. The NIRC Rosh Kollel, Rav Ezra Neuberger, describes those derashos as “electrifying.”

Reb Yonah also serves as the Maggid Shiur in Residence at Shomrei Emunim, a large and very diverse shul, where he delivers Yom Tov derashos and on other occasions throughout the year. “As many shiurim as he can give, we can pack the shul,” Rabbi Binyamin Marwick, the shul’s rav, told me. “He appeals to Briskers and college graduates alike; his command of the sources is absolute, and the shiurim are delivered with infectious enthusiasm.”

Rabbi Marwick points to another trait that draws large audiences: “For such a baal kishron, he is genuinely interested in what others think. When people gather around after a shiur, he listens attentively and with no signs of impatience to both their questions and their insights.”

Reb Yonah describes his father as risk-averse, in contrast to his own out-of-the-box style. But they share a delight in Torah learning and life

A Tapestry of Many Threads

That same palpable joy in learning is evident in Rabbi Sklare’s first English-language work, The Breathtaking Panorama: A Sweeping Thematic Approach to Yetzias Mitzrayim. (He has previously published eight kuntreisim on the tractates primarily learned in yeshivos.) One of his goals in writing the sefer, he tells me, was to demonstrate how “Torascha sha’ashuay — Your Torah is a delight,” means that Torah learning can be at once creative, even playful, and rigorous.

He compares his methodology — a methodology into which he was first inducted by Rav Nachum Lansky in Ner Israel — to that of a detective. A detective begins by assembling all the clues, the various anomalies that don’t fit. So, too, the student of Torah is alert to “textual anomalies — unusual phrases, unanticipated expressions, words that are loaded with evocative undertones,” as well as “echoes of other passage that show themselves to be ‘sister passages.’”

Gradually, a tapestry emerges that fills the student of Torah with a sense of discovery of something substantive requiring further exploration and development. The detective seeks to answer whodunit; the student of Torah asks, “What is the Divine Author seeking to teach me about my life and my relationship to him through Torah?”

The more details and anomalies that fit together, the more one feels that Torah is temimah, all-encompassing. This non-linear, midrashic development is at once expansive and liberating.

Of the themes developed by Rabbi Sklare in The Breathtaking Panorama, Rav Aaron Lopiansky, rosh yeshivah of the Yeshiva of Greater Washington, writes to him, “I… was astounded by the magnificent tapestry you weave, from so many different sources with brilliance and depth! The value of these essays lies not only in the rich content, but perhaps more important in the kavod HaTorah generated by them, when people realize the astounding depths and endless complexity of Hashem’s Torah. In a generation raised on soundbites, it is amazing to see the patience and effort that went into developing these broad and sweeping essays.”

On that last point, Reb Daniel Sklare shared with me in a Zoom conversation, “My son has been developing the core themes of his sefer since he was 16 years old.” (He is now 39.)

There is no point in trying to summarize the three major themes of The Breathtaking Panorama — Family, Faith, and Freedom — without the myriad of details from which the tapestry emerges.

What can, however, be said with confidence is that with its publication, the blessing given to the young Daniel Sklare by the Steipler Gaon nearly 60 years ago — “Your sons will light up the world with the light of their Torah” — has been fulfilled.

As for what Marshall Sklare would have thought of his grandson’s accomplishments, Reb Yonah has no doubts. “It never occurred to me that my grandfather would not have been proud of me. I champion the same values that he did — the pride and excitement in being Jewish — but I’m able to do so through Torah.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 955)

Oops! We could not locate your form.