To Mourn or Not to Mourn

| May 23, 2023American Jews now found themselves caught between their desire to express solidarity with the nation and reverence for Lincoln, and the need to observe the traditions of their faith

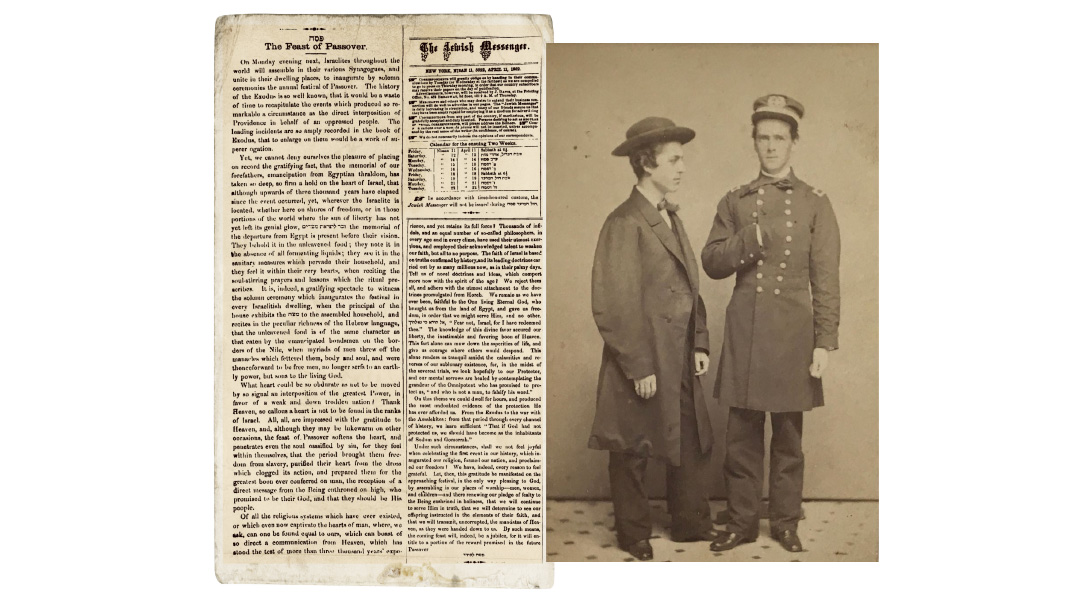

When President Lincoln was assassinated on Shabbos Chol Hamoed Pesach, rabbis across America were faced with the task of eulogizing the “Great Emancipator” with no advance notice. Those who held off until after Pesach were faced with a similar dilemma on Shavuos — the day of national mourning chosen by President Andrew Johnson

Title: To Mourn or Not to Mourn

Location: United States of America

Document: Sermon by Rabbi Sabato Morais

Time: Pesach 1965

Murmurs of ill tidings circulated as Jews congregated at synagogues across America on the morning of Shabbos Chol Hamoed Pesach in 1865. The previous night, President Abraham Lincoln had been shot by John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., and the disheartening news of his passing early that Saturday morning had just started to reverberate.

In response, newly sworn-in President Andrew Johnson called for a national day of mourning on May 25, which was to include gatherings in houses of worship to remember the late president. Christian clergy objected that it would coincide with their holiday of Ascension Day, so President Johnson agreed to postpone the commemoration to June 1.

A Proclamation

Whereas by my proclamation of the 25th day of next month was recommended as a day for special humiliation and prayer in consequence of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, late President of the United States; but Whereas my attention has since been called to the fact that the day aforesaid is sacred to large numbers of Christians as one of rejoicing:

Now, therefore, be it known that I, Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, do hereby suggest that the religious services recommended as aforesaid should be postponed until Thursday, the 1st day of June next.

In testimony whereof I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the city of Washington, this 29th day of April, 1865, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-ninth.

ANDREW JOHNSON

That date would fall out on 7 Sivan, the second day of Shavuos, presenting a dilemma for American Jewry. The reaction was swift, with spiritual and communal leaders turning to the press to publicize their view that the Shavuos Holiday — as with all Jewish festivals — was a religious time of rejoicing, with celebrants forbidden to express mourning or grief.

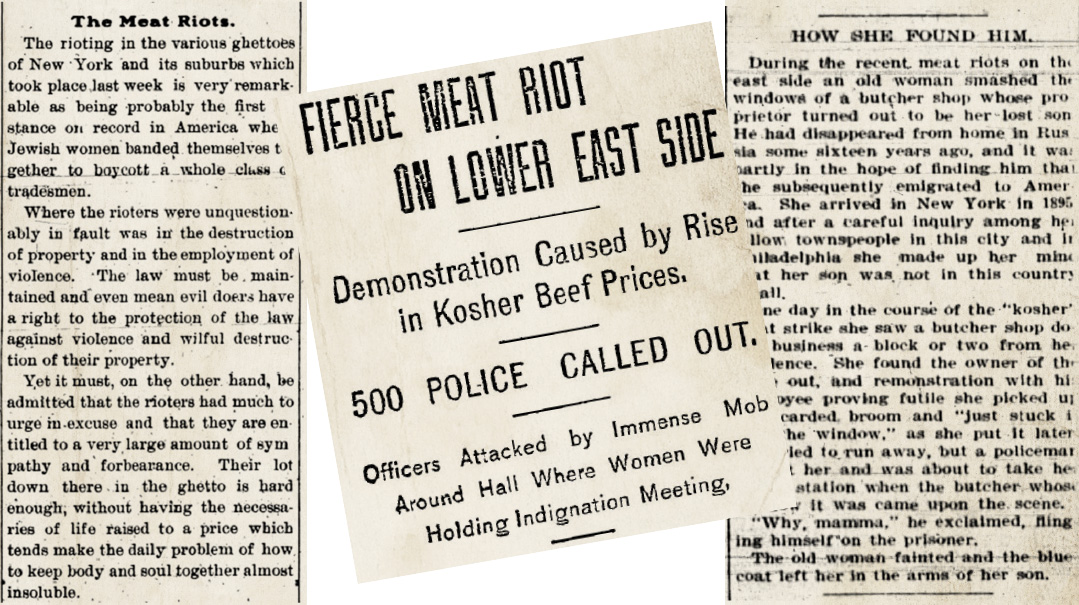

American Jewry had seen significant demographic growth in the first half of the 19th century. From modest beginnings in the Colonial era of some 2,000 Jews primarily of Sephardic origin, a large influx of German Jewish immigration from the 1820s onward brought the figure to more than 150,000 by the outbreak of the Civil War. Many were assimilating into American life, while others built Reform Judaism, and a small minority held on tenaciously to traditional Jewish observance.

American Jews now found themselves caught between their desire to express solidarity with the nation and reverence for Lincoln, and the need to observe the traditions of their faith. How could they participate in a national day of mourning while simultaneously honoring the joyous celebration of Shavuos, which explicitly called for “gladness and rejoicing”? This challenging conundrum was compounded by the fact that Jews had immigrated to the United States in order to evade religious persecution and enjoy the freedoms guaranteed under the Constitution.

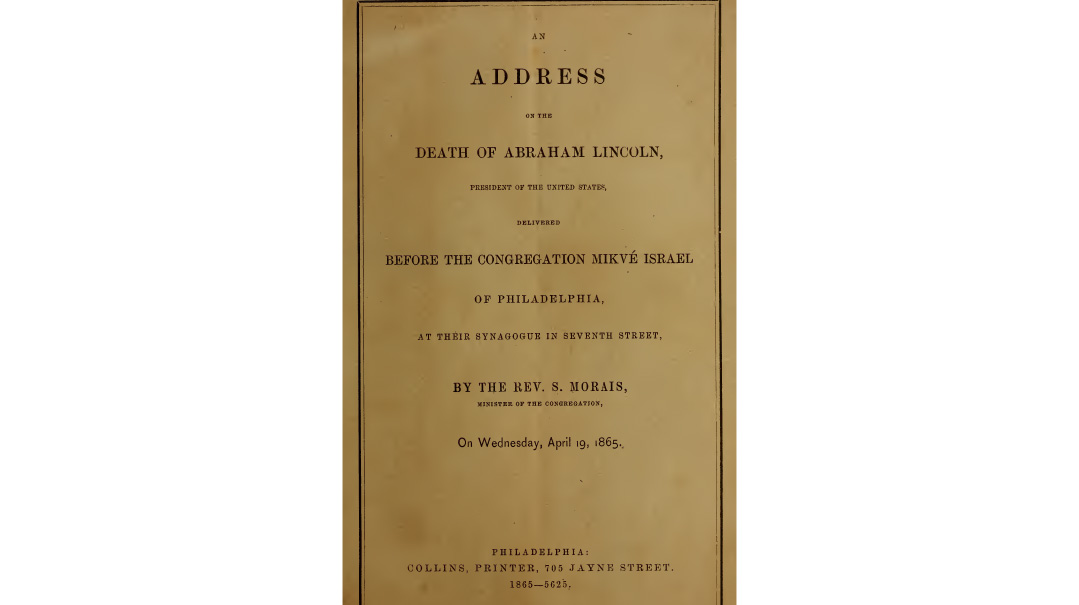

Rabbi Sabato Morais headed Philadelphia’s Mikveh Israel from 1851 until his passing in 1897 and was the country’s acknowledged leader of traditional Judaism. A Yiddish journalist referred to him as “der grester fun alle Orthodoksige rabbonim in America... ein sufik.” Morais was Italian-born and belonged to a strongly Republican family. He urged his congregants to observe the national day of mourning and humiliation without reservation. In his view, religious communities could best engage with the public square by complying with the broader American civic spirit.

A different, perhaps more creative view was expressed by Jacques Judah Lyons, a Suriname born-and-bred rabbi of New York’s legendary Congregation Shearith Israel. Among his achievements were the founding of “Jew’s Hospital” in New York (eventually Mt. Sinai), and an initiative to publish the first 50-year Jewish calendar in the country. His niece was the famous poetess Emma Lazarus, who authored the sonnet “The New Colossus” inscribed on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty. Lyons, a respected spiritual leader, was eulogized after his passing by a congregant, “I think he approached and seemed to be nearer a man of G-d than any clergyman I ever saw or knew.” Like Morais, Lyons was an ardent patriot who profoundly admired Lincoln.

Unlike his colleague in Philadelphia, Lyons insisted that his congregation not observe the day of mourning out of deference to the Shavuos Holiday. In remarks offered on that very day, Lyons argued, “The rules of our ritual prohibit every demonstration of sorrow and all supplicatory invocation on this day of joy. But for this restriction, we, too, in common with our fellow-citizens of all denominations, would have observed this day of humiliation.”

Lyons was determined, however, to commemorate Lincoln’s memory in an authentically Jewish manner. He noted the widespread practice on major Jewish holidays like Shavuos to recite Keil Malei, the Jewish prayer for the souls of the departed. “In this spirit,” Lyons explained, “believing that the merits of our departed president will find favor with an all-merciful G-d, let us pray for the reception of his soul into the kingdom of Heaven.”

For Lyons, the American public would not be well served by its Jewish constituents compromising their faith in the name of social cohesion. Instead, “The greatest gift that faith communities could give to the public square is to maintain the courage of their convictions and so bequeath their unique traditions of wisdom to America as a whole.”

On the cusp of the American Jewish community’s emergence as the largest in the world, its members faced a unique struggle over their identity. The paradox of the American Jewish experience was that many had been drawn to this country by the tantalizing proposition of religious freedom and equality. The limitless opportunities offered in this new land made integration possible and loyalty to their new home both imperative and desirable.

Yet that milieu presented the challenge of navigating traditional Jewish life within the framework of freedom and equality. After a national day of mourning for the slain beloved president on the festive holiday of Shavuos, American Jewry would spend the ensuing decades defining itself within the boundaries of both Jewish tradition and civic participation.

The Gettysburg Sermon

It has been speculated that a sermon delivered by Rabbi Sabato Morais influenced Abraham Lincoln’s phraseology in his Gettysburg Address. On July 4, 1863, while Union General George Meade was overseeing the retreat of General Robert E. Lee’s defeated Confederate army following the Battle of Gettysburg, Rabbi Morais was asked to make a reference to Independence Day by the Union League of Philadelphia.

He referenced the 87th anniversary of American independence: “I am not indifferent, my dear friends, to the event which, four score and seven years ago, brought to this new world light and joy,” a reworked version of the words of Tehillim 90:10. The sermon was printed in newspapers the following day, and may have influenced Abraham Lincoln’s wording in the Gettysburg Address delivered in November.

Initially Lincoln had referred to the age of the Union as “eighty-odd years.” At the dedication of the Gettysburg cemetery three months later, Lincoln elevated his discourse to “four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth to this continent,” which echoes the phrasing used by Morais in his sermon. Rabbi Morais perhaps made a lasting contribution to American rhetorical history.

Saving Private Michaelis

Over two-thirds of American Jews at the time of the Civil War were recent immigrants, primarily from the German states of Central Europe. Thousands served in both the Confederacy and the Union, with many losing their lives on the battlefield. Three sons of Minna Michaelis enlisted in New York regiments following their recent immigration from Hesse, Germany. They used their first army paychecks to bring over their impoverished parents and eight siblings, who then settled in Brooklyn. Moritz died in the service from typhus, Charles was killed in action at Antietam, and August died of tuberculosis 15 years after being wounded at Antietam and discharged for disability. The devastated parents were left with “the solemn pride that must be yours to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of Freedom,” as President Lincoln would write to a similarly bereaved Union parent, Lydia Bixby.

A Humble Moses

An article in the Hebrew Leader reported that when news of Lincoln’s death arrived in London, Sir Moses Montefiore — who dedicated his life to helping persecuted Jews across the world — uttered the following memorable words: “Lincoln has liberated the black race from its bondage and chains, and fell. I wished G-d would endow me with the strength and energy of a Lincoln, that I might break the fetters of my people in the vast half-civilized kingdom of the Czar, and deliver them from their shameful bondage in Morocco. Hundreds of thousands of my brethren are longing for the arrival of a Lincoln, a liberator; willingly would I die the death of Lincoln if by it I could achieve the emancipation of my white brethren.”

The article concludes: “And with this ‘Jewish Wilberforce’ [a reference to the British emancipator William Wilberforce], this is no empty speech. Montefiore went, in his eighty-first year to Morocco, in order to put a stop to the bloody persecution of Jews and Christians.”

Research by Rabbi Dr. Ari Lamm, Dr. Jonathan Sarna, and Dr. Adam Mendelsohn was utilized in the preparation of this article.

This week’s article is presented in honor of the bar mitzvah of Menachem Schwartz of Lawrence, New York, a budding talmud chacham as well as a presidential history buff.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 962)

Oops! We could not locate your form.