The Vault is Open

Famed gadol photographer Moshe Dovid Yarmish opens his vault of priceless gedolim photos, his iconic images of a nation’s leaders

H

e works in finance, lives in an attractive Flatbush home, and when I first came to see him several years ago, he wasn’t sure what I wanted. Yeah, he had pictures, boxes of them, envelopes jammed with negatives, and maybe he would release them.

Someday. It would be nice.

I visited Moshe Dovid Yarmish before the 25th yahrzeit of Rav Moshe Feinstein and Rav Yaakov Kamenetzky, eager to speak with my host for a special tribute issue this magazine was planning.

It was clear to me then that the photographer didn’t really understand what his name meant to a child of the 80’s who grew up collecting, chasing, trading, shuffling rebbi pictures. Those photos are how we first learned of Chacham Ovadiah’s rounded hat and the Kaliver Rebbe’s colorful beketshes. The Belzer Rebbe stood out for his youth and Rav Moshe Feinstein’s yarmulke fascinated us — so, along with the rush of nostalgia comes respect for the names in the corners or backs of those pictures: Trainer Studios, of course, and the gold-script of M.D. Yarmish.

M.D. Yarmish himself laughed when I told him what he meant to us. He was never a celebrity photographer, meaning he’d never been part of the story. It was never about what he’d said to the gadol or how the gadol had reacted to him; in most cases, they didn’t even know what he was doing. He was a bochur enjoying himself, using the money that came in from the pictures to fund more picture-taking. As hobbies go, it was time-consuming and costly: he traveled to Eretz Yisroel to capture its giants but was able to pay his own way. When the Belzer Rebbe traveled to Montreal in the late 80’s, M.D. Yarmish was on site. As soon as the pictures were ready — and it took time back then, to send them out and daven and wait and hope — he took fresh prints to the Belzer shtibel in Boro Park and sold them, covering his travel expenses.

He was sitting on a treasure-house of pictures, I told him, and we parted amidst vague, laughing references to “someday,” that time when the vaults would open.

Time for Nostalgia

Then COVID-19 hit.

A Wall Street Journal article tried to make sense of the ensuing spike in baseball card prices, which had been stagnant for years. During the lockdown, the article explained, people suddenly had time to sort through old boxes and closets. A therapist suggested that people were desperate for the comfort of their childhoods, and the cards brought them back to a simpler time. “They’re reminiscing,” a collector and current baseball player commented. “A lot of this surge for non-vintage cards [comes from] people who are bored at home buying cards they couldn’t have when they were younger, totally nostalgia- driven.”

There is no index or price system for collector cards in the frum world, but nostalgia is universal. And if sports memorabilia is about childhood cravings, then gedolim pictures are about childhood dreams.

When the virus descended on New York, Moshe Dovid Yarmish — whose Wall Street office was closed — found himself with a bit of extra time and a sense that the people around him could use a boost.

Someday had arrived.

He started releasing not just photographs, but video clips — and who had video back then? Suddenly, locked into our homes, we could see Rav Moshe speaking in learning and Rav Shach on the steps following shiur klali, surrounded by an army of shouting talmidim. The Bluzhever Rebbe grasping a Torah in his frail arms against strains of the very niggun to which so many of his chassidim had walked to their deaths, and the Satmar Rebbe’s tearful hesped at Rav Moshe Feinstein’s levayah.

First through private correspondence and groups, and eventually, on social media, each new offering shot through the frum world like a meteor: a jolt of holy nostalgia, a reminder of the generals of a generation ago. It wasn’t just the luminous faces of tzaddikim that gripped us, it was the time — the people around them, the cars and furniture and worn seforim.

I suspect I’m not the only one who watched each clip more than once, looking for clues and finding the comfort Reb Moshe Dovid had hoped to provide.

“I Still Feel the Fear”

As a bochur in Torah Vodaath, Moshe Dovid came in to the industry out of love: he always enjoyed taking pictures, and his maternal grandfather, Rabbi Tzvi (Harry) Bronstein — hero of Russian Jewry, activist, shul rabbi and author of seforim — provided him with access to the gedolim of the era.

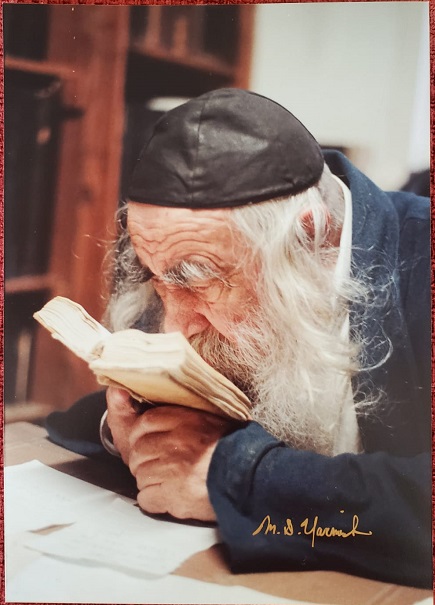

It was with Rabbi Bronstein that Moshe Dovid earned entry to the Steipler Gaon, Rav Yaakov Yisroel Kanievsky.

“I look at this picture and I still feel fear,” he says. “The Steipler was an awe-inspiring figure and he didn’t want pictures taken of him. My zaide went in, and I joined him, but I didn’t plan to take a picture. I just couldn’t do it, I was frozen. But my grandfather motioned for me to snap, and then he did it a second time, so I listened. It’s thanks to him that we have this picture, which means so much to talmidim of the Steipler and gives over some of that awe that you felt in his presence.”

It would also become the cover image of the ArtScroll biography of the Steipler, an enduring image of the great man bent over a sefer, toiling in learning.

“You See the Sweetness”

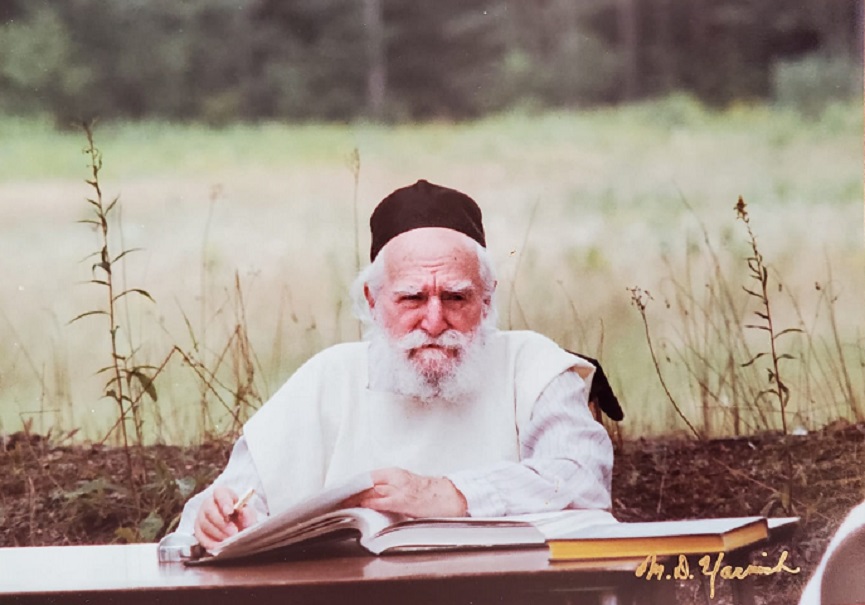

The most requested picture, and the one that means a lot to the photographer personally, is of Rav Moshe Feinstein. It’s one of many pictures of Rav Moshe, because Moshe Dovid would spend his summers in Kerhonkson, New York, with the Yeshiva of Staten Island.

“In camp, the family was even more protective of Rav Moshe,” he remembers. “That was his time to simply sit and learn, undisturbed. I would take the pictures without being seen, and eventually, I amassed quite a collection. After Rav Moshe’s petirah, I lent a whole album of pictures to his son, Rav Dovid. This one is special, because you see the sweetness of Torah on his face, the pen clutched in his hand ready to commit the stream of holy thought to the page.”

A Moment in Time

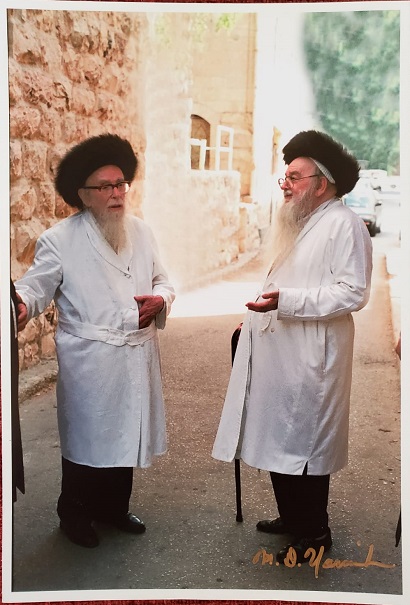

Perhaps the most iconic picture is that of Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach and his brother-in-law, Rav Sholom Schwadron. Moshe Dovid and his new wife were in Yerushalayim for Yom Kippur, but on erev Yom Kippur, the young husband asked permission to slip away.

“I was taking pictures of Rav Shlomo Zalman as he left the Gr’a shul in his kittel, and I didn’t plan for this — but he met his brother-in-law and both men, already in kittels and shtreimlach, stopped to wish each other a g’mar chasimah tovah. The picture is about them, their relationship — but also about the time and the neighborhood.”

Portrait of Triumph

Moshe Dovid learned that even in those courts in which picture-taking wasn’t encouraged, there was always someone inside who understood that one day, the images of a tzaddik would be appreciated. These insiders would tip him off where to be, when to come, confident that he would capture the magic without making a scene. He has rare pictures and videos of the rebbes of Satmar, Vizhnitz, Tosh – and even when it comes to Lubavitch, where pictures were constantly being taken and there was a live video feed, he has managed to capture video showing unseen angles and moments.

Still, this picture is special, he feels. “It shows the Bobover Rebbe holding his daled minim aloft, species that represent triumph, in an image that itself cries of triumph: a man risen from the ashes to build and preside over a kingdom. If a story that dramatic can be captured in a picture, I guess this is it.”

Holy Toil

Rav Shach against the backdrop of the glorious golden Ponevezher aron kodesh is a special image, but when Moshe Dovid visited Ponovezh he wanted something else — the story of the Rosh Yeshivah by his shtender, bent over in a picture of perfect horevanyah, a ben Torah between bnei Torah, talmidim learning all around him.

“It’s a picture of ameilus baTorah,” he says. “I was good friends with Asher Bergman, Rav Shachs’s grandson, and he allowed me access. It was special to be able to capture that.”

A Smile That Speaks

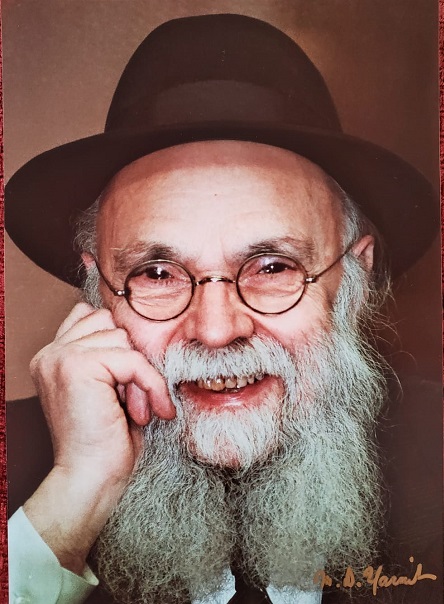

Then there is a picture of his own rosh yeshivah.

“As a talmid in Torah Vodaath, I had a close relationship with Rav Pam,” he remembers. “I would record his shiurim and shmuessen, and he knew that I sometimes took pictures, too. He was very gentle and pleasant, of course, and always made me feel comfortable. This picture tells you everything about his nai’mus, the sweetness that poured out of this Yid, the Torah and yiras Shamayim and middos all come together in that glowing smile.”

Mutual Respect

Finally, the most meaningful picture, the one that the photographer has as his own avatar, is that of his beloved zaide, Rabbi Bronstein, with Rav Moshe, also taken in camp. “It’s a picture that shows friendship, mutual respect, and the overwhelming radiance of Rav Moshe’s face as they look together into a sefer.”

After so many years keeping his vault closed, the current feedback to each offering, picture or video, has been heartening for Moshe Dovid. “I never had this format, where I can get hundreds of comments and requests for purchase within minutes.”

People want not only the footage and image, but the chance to pore over every face in the background, to recapture, revisit and remember.

The lockdown of 2020 — may it end quickly — will be remembered for many things. In our community, we will recall mourning and simchah, incredible chesed and heroism. And we will remember, too, the generosity of a photographer who allowed so many of the gedolei Yisrael whose Torah we learn and inspiration we so badly seek, to come back to life, if only for a moment or two.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 812)

Oops! We could not locate your form.