Tears, Ashes, and Grit

Even more than they needed the brachah, those survivors needed to bask in the reassuring glow of the tzaddik’s presence

Poalei Agudas Yisrael

Bnei Brak, Israel

Rabbi Moshe Grylak

Idon’t remember being inside a shul until I was ten years old.

Until then, I’d been a child refugee on the run from the Nazis. By the time I was six years old, I’d already fled from Belgium to France and then to Switzerland. I’d been separated from my parents and forced to assume responsibility for my little sister in a strange new country.

In 1945, our family was reunited and we left a scarred Europe behind to make aliyah. We settled in the fledgling city of Bnei Brak, and I began to reclaim the childhood that had been snatched away: friends, games, cheder, and shul.

Our shul, known as the “Pai Shul” — an acronym for Poalei Agudas Yisrael — was housed in a classroom in the first and only Talmud Torah at that time in the city of Torah and chassidus: Talmud Torah Rabi Akiva. All week during regular school hours, young boys learned there. During off hours, the desks and chairs served as the shul’s furniture, with the addition of a plain aron kodesh, the type found on army bases today.

Most of the mispallelim were Holocaust survivors, still reeling from the traumas they’d been through. Each of them had left someone behind — a father, a mother, brothers and sisters, a wife and children, if not all of the above. During the daytime routine, they’d try to rebuild. But after davening, they’d linger in little groups and talk.

As a little boy, I would hover in the shadows and listen as they reminisced about their horrific experiences in Auschwitz, in the ghettos, in hiding, in the forests, and so on. I don’t remember much of what they said, but the atmosphere in that classroom-turned-shul still lives in my subconscious.

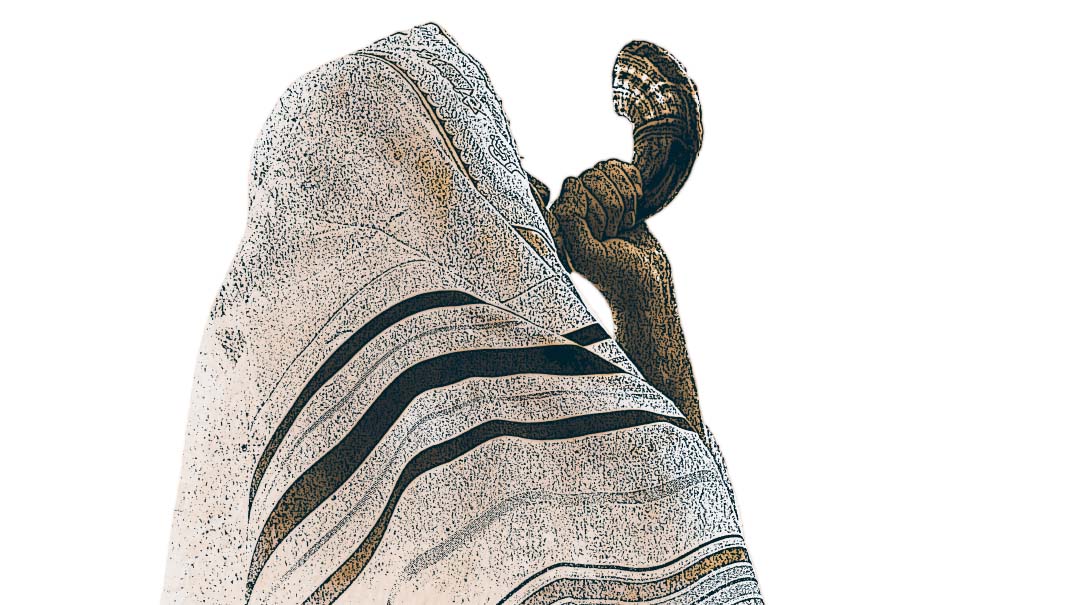

I remember a pair of brothers, both veterans of Auschwitz, the sole survivors of their entire extended family. One of them, I recall, was called Menachem. He had a wonderful tenor voice. On Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur he was king, reigning over the tefillah as shaliach tzibbur with a fluid command of all those old melodies from “back home.” Even to a child like me, the emotion in the room at those moments was palpable. I could tell that each man was being transported somewhere across the Mediterranean — one to Lublin, another to Warsaw, another to Radomsk. And when our baal tefillah poured out passages that spoke of Divine punishment or that begged for Divine aid, his voice would sometimes crack, and his raw emotion broke down the barriers of hard-won restraint as the room of toughened survivors rocked with loud cries. I remember how, with childish curiosity, I would go up to him at the end of davening to get a look at his face. Under the folds of his tallis, it was reddened and spent.

Despite the post-traumatic stress that afflicted the men in my little shul, these congregants made every effort to return to normal life. They married and raised families, for the second time in some cases, and they worked hard to earn a living in a new, at times very foreign environment. Simplicity, not to say poverty, was evident among them all. Making do with little was a fact of life in those postwar years, and shul life, too, was characterized by extreme frugality.

My bar mitzvah was celebrated there in the Pai Shul. I got the customary aliyah and read the haftarah, and afterwards all were invited to a lavish spread of… crackers and herring. Try as I might to remember, I can’t recall anything more being served. Did I receive presents? Yes, about ten or fifteen sefarim. No, not sets. Small volumes such as Mesillas Yesharim and the like.

Life was tough, life was gritty. But we had our warm and fuzzy moments, too. Perhaps because there was so few of them, they burn especially bright in my memory.

After davening on the first night of Rosh Hashanah, no one went straight home. The whole minyan would walk, as a matter of course, to the home of the Chazon Ish to wish the gadol a good year and receive his brachah in return. And there we would witness an amazing sight.

I’d seen so much, traveled so far, in my tumultuous childhood. But this sight always stopped me in my tracks. With the close of davening that night, everyone, from every shul in Bnei Brak, would make their way to that same address, all waiting for their turn for that treasured yearly blessing. And the tzaddik would stand there at the door for as long as it took, blessing every one of them, man or boy, with the full traditional brachah of the night, the radiance never fading from his face.

When I think back to that scene, I realize that even more than they needed the brachah, those survivors needed to bask in the reassuring glow of the tzaddik’s presence.

And to the little ten-year-old who watched it, mesmerized, that would remain the most enduring memory of my first shul.

Rabbi Moshe Grylak is a child survivor of the Holocaust who later attended Yeshivos Kol Torah and Ponevezh. He is a pioneer in the worlds of outreach, Orthodox journalism, and fiction-writing. He served as the founding editor of the Hebrew-language Yated Ne’eman and has been the editor-in-chief of Mishpacha magazine for more than three decades.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 876)

Oops! We could not locate your form.