Supporting Role

For Dr. Marvin Schick, no Jewish child could be left behind

Purim 1938. A day of great joy turned abruptly into one of devastation for Renee Schick, with the sudden death of her husband, Rabbi Joseph Schick, a Romanian émigré who served as rabbi of the West Side Jewish Center on Manhattan’s 34th Street. The young mother of four children, including three-year-old twins Marvin and Allen, was left with no means of support and, when the Schicks were evicted from their apartment just weeks later, without even a roof over their heads.

The next years were excruciatingly difficult ones; young Marvin was hospitalized with diphtheria, then Allen with pneumonia, and all throughout, their mother struggled mightily to provide for her children. Eventually, she’d go on to open the famed Schick’s Kosher Bakery on Boro Park’s 16th Avenue, above which she and her children made their home.

Those early years of tears and travail became the crucible out of which Marvin Schick became the peerless paradigm of a Torah lay leader. But to truly appreciate the magnificence of his achievement-packed life — and the profound loss the Jewish world suffered with his recent passing at age 85 — one must know not only who he was but also what he was not.

He was not a lawyer — yet he was a pioneer in securing legal rights for frum Jews in the workplace and in pursuing government aid for yeshivos. He was neither a rebbi nor rosh yeshivah — yet he founded and funded multiple Torah mosdos and was a seminal figure in the flourishing of chinuch across the country. He wasn’t a wealthy magnate — he didn’t own his own home or even a car — yet he was responsible for tens of millions of dollars flowing into day school and yeshivah coffers throughout North America. He wasn’t a marbitz Torah — yet hundreds now study the works of great marbitzei Torah that he published. Nor was he a “kiruv professional” — yet untold numbers of Jews are observant today due to his efforts.

Marvin’s formative experiences of pain and privation were surely the springboard for the visceral empathy he felt for every Jewish child denied his Jewish educational birthright, every parent straining to afford tuition bills, every rebbi striving to transmit the Torah on to the next generation despite his position’s low prestige and even lower salary. Yet his nearly seven continuous decades of askanus for Klal Yisrael might never have come to be were it not for an early, transformative encounter with greatness.

Rebbi for Life

While still a teenage student at the Rabbi Jacob Joseph School (RJJ) high school on the Lower East Side, Marvin was invited, in the fall of 1951, to attend a meeting convened by Rav Aharon Kotler to inspire young people to communal activism. The 17-year-old was instantly captivated by the idealistic passion of Reb Aharon’s message, delivered rapid-fire, his clear blue eyes ablaze. And thus began an unusual, decade-long rebbi-talmid relationship.

The brilliant, articulate, all-American young man who never spent a day in kollel became a frequent companion of the sagacious leader of American Torah Jewry, a lieutenant in Rav Aharon’s battle for the primacy of Torah over all else. Soon, Marvin’s fundraising efforts on behalf of Chinuch Atzmai, the then-fledgling Torah Schools for Israel network championed by the venerable Lakewood rosh yeshivah, were yielding $3,000 a month, a full 20 percent of what Rav Aharon had committed to send overseas to the organization.

The affection and esteem were mutual. Although Marvin would humbly muse that he was “never able to fully understand” what Reb Aharon saw in him, the Rosh Yeshivah certainly knew. What he saw even then, says Mrs. Malka Schick, Marvin’s wife of 58 years, was that “he possessed so many outstanding gifts with the ability to interweave them all, using them in tandem in such a focused, meticulous way to work for the klal and do what was right and just. He had a towering intellect and vast knowledge, long-range vision, and the insight to size situations up quickly. He had an exuberant personality, a boundless heart filled with empathy, and a desire to help the underdog. Perceiving all that, Rav Aharon charged him with his life’s overarching mission, to get involved on Klal Yisrael’s behalf, and that propelled him forward throughout his life.”

The lessons Marvin learned at the Rosh Yeshivah’s side became his guidepost for life. Once, when they traveled together to Manhattan to solicit a donation from a well-to-do businessman whose response was very disappointing, Rav Aharon thanked the man warmly. Afterward, when Marvin expressed disappointment in the donation given and surprise at the Rosh Yeshivah’s response, Rav Aharon explained, “This man is obligated to give tzedakah, but not specifically to our cause, and if he does give, we owe him hakaras hatov regardless of how much it is.”

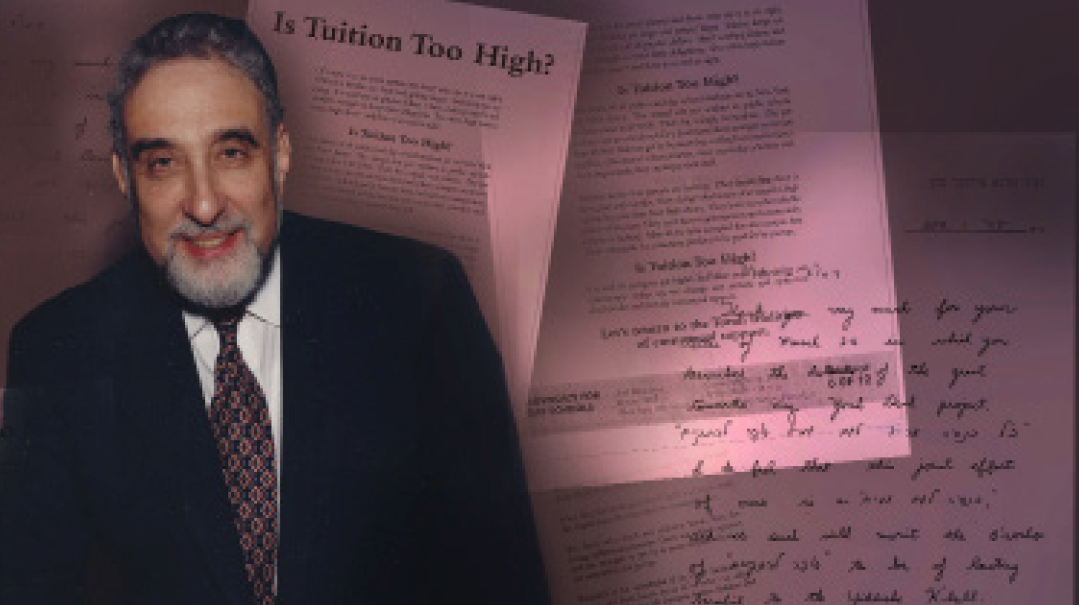

Rav Aharon believed that whenever possible, thank-you notes and receipts were to be sent to donors within a day after the contribution was received. And indeed, Marvin Schick spent hundreds of hours handwriting such notes to supporters of the yeshivos he led, without regard to whether the recipient had given five dollars or fifty thousand.

Renowned New Jersey philanthropist Yossi Stern, who worked with Marvin for decades on behalf of the yeshivah gedolah in Edison, the crown jewel of the RJJ family of Torah institutions, recalls that Marvin would write thank-you notes before he even got the checks, never missing an opportunity to express hakaras hatov. He calls Marvin Schick his “rebbi in askanus,” who, he says, “was a talmid who had the fire of Rav Aharon burning within him. Marvin never learned in Lakewood, but while Rav Aharon gave over his Torah to his talmidim, he handed the torch of askanus to Marvin, who took it and ran with it his whole life.”

Although Rav Aharon and his rebbetzin lived in Boro Park, just a block away from the Schicks, he always spent Shabbos in Lakewood, giving one of his two weekly shiurim then. Marvin was needed to pitch in at his mother’s bakery on Fridays and thus could not accept the Rosh Yeshivah’s numerous invitations to join him for Shabbos. One week, however, he did manage to get away to Lakewood, and Rav Aharon invited him to eat at his table in the dining room, a privilege reserved for the most outstanding talmidim.

Marvin found himself sitting between Meir Stern and Moshe Hillel Hirsch, today the roshei yeshivah of Passaic and Slabodka, respectively, who were close friends and former RJJ talmidim. Rav Aharon honored Marvin with leading the bentshing, and as he recalled later, “Rav Meir and Rav Moshe Hillel kibbitzed me about the honor that had been accorded to me. I was more than nervous and my hands were shaking. By the time the first brachah was completed, there was scarcely any wine left in the kos.” Looking back and knowing just how faithful a disciple of the Rosh Yeshivah Marvin was to become, the picture of him sandwiched between those two great talmdim doesn’t seem so strange at all.

New Voices

Marvin and Malka married in October 1962, just three weeks after the passing of Rav Aharon, who had been slated to be mesader kiddushin at their wedding. By then, Marvin was completing his doctorate in political science from NYU, spending his breaks between classes in nearby Washington Square Park — taking on all comers in consecutive chess matches or sitting on a bench doing the New York Times crossword puzzle.

He began a decades-long teaching career in political science and constitutional law at Hunter College and the New School for Social Research, and published a Johns Hopkins University Press volume entitled Learned Hand’s Court, a well-received academic study of the influential jurist Learned Hand’s impact on the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, the country’s foremost federal appellate court.

In 1965, Dr. Schick made his first major foray into the public arena as an advocate for Orthodox Jewish communal interests, joining with Rabbi Moshe Sherer and Staten Island attorney Reuben Gross to found the National Jewish Commission on Law and Public Affairs (COLPA), with Dr. Schick serving as its first president. Its stated mission was a broad one: to secure and defend the rights of Orthodox Jews in regard to things like Shabbos observance, kosher food and religious attire, and to advocate for government aid for day school and yeshivah students.

COLPA also served another, unstated purpose: It put the secular Jewish establishment — the so-called “alphabet soup” of groups like the AJC, ADL and NCRAC — on notice that the Orthodox Jewish community was coming into its own, growing in numbers and clout and with a cadre of homegrown professionals ready to do battle in the courts of law and public opinion, many of them frum attorneys with Ivy League credentials but unable to find employment due to discrimination. On the issue of government aid for yeshivos in particular, COLPA represented a dynamic new voice of dissent to the secular Jewish groups which implacably opposed such aid, led by AJC general counsel Leo Pfeffer, with whom Dr. Schick engaged in a 1968 debate shown on public television and reported on in the New York Times.

A 1970 Newsweek article on COLPA featured a picture of Marvin Schick leaning back insouciantly at his office desk, alongside a quote: “We have no dinners, no banquets or plaques… But we are willing to stand up and fight.” On COLPA’s 40th anniversary, he reflected in print, “We were advocates, even fighters, and we weren’t afraid to be militant or unpopular…. We focused on issues and outcomes, testifying before Congress and other legislatures, writing briefs and promoting through the media what we believe was right. We were effective to an extent that we could scarcely predict and we gained the respect of organized American Jewry.”

Dennis Rapps, who came aboard as COLPA’s executive director in 1970, observes that at the outset, the main focus was not on employment discrimination, but on making the case in the courts that the First Amendment had been grossly misunderstood as an insurmountable bar to public funding for even entirely nonsectarian aspects of yeshivah education. “Although Dr. Schick wasn’t a lawyer, he had in-depth knowledge of how the appellate courts worked, and thus he was able to guide the original team of lawyers, who were tax and trial practitioners rather than appellate specialists, until Nathan Lewin came along, who was, of course, a top-flight appellate attorney,” says Mr. Rapps.

Schick’s major contribution, according to Rapps, was as a visionary strategist who was the first to conceptualize the withholding of public aid to yeshivah students as a form of discrimination. Known as child benefit theory, this is the idea that yeshivah students, no less than other children, are entitled to public education, they just don’t take advantage of it, but vouchers enable them to do so. He notes that “in more recent years, there have been several decisions that have reflected the arguments we made in those early years, as Marvin’s platform that this was discrimination against yeshivah children germinated over time.”

For Dr. Schick, the late 1960s and early 1970s were a time of sustained political and communal involvement extending well beyond the confines of the Orthodox Jewish community. In 1970, while spending a sabbatical year on the Bar Ilan University faculty, a call came from the newly elected Republican mayor of New York City, John V. Lindsay, asking Marvin to join his City Hall staff, where he ultimately served as the mayor’s administrative assistant. A news item announcing the appointment describes him, at the tender age of 35, as not only a past president of COLPA, but also an executive committee member of the National Community Relations Advisory Council, chairman of the OU’s Communal Relations Commission, and the American Civil Liberties Union’s representative at the United Nations.

He even found time in 1977 to run, albeit unsuccessfully, for Brooklyn borough president. That same year, a dark-horse former Congressman named Ed Koch was running for mayor, and Marvin Schick was the first person to endorse the man who went on to win the first of three terms in office.

Help Every Child Thrive

With the close of his tenure with the Lindsay administration in 1973, a new chapter opened in Marvin Schick’s life. Incredibly, every five years for the next two decades, he established a brand-new school or completely revamped an existing one. All of this intensive institution building took place under the umbrella of RJJ, the venerable “mother of the yeshivos” and a Lower East Side fixture since before the turn of the century. But with the yeshivah’s glory days long gone, it was now a nearly moribund institution with little to its name but a small and shrinking high school and two dilapidated buildings in an ethnically changed neighborhood.

In late 1974, Irving Bunim, the legendary lay leader who, like Marvin, had been an intimate of Rav Aharon Kotler, asked Marvin to assume the presidency of RJJ. Where any reasonable person would have run the other way, Marvin ran toward the opportunity, which would enable him to act on a defining theme of his life: Taking responsibility, even — or especially — where others have shirked it.

Rabbi Yaakov Feitman, Dr. Schick’s choice as founding principal of RJJ’s Staten Island elementary school, describes him as “someone who saw something that needed to get done and said I’m going to do it. He couldn’t understand why others didn’t act, and they didn’t understand how he could take on yet another responsibility. But he did.” Marvin accepted the role of president without compensation, and never looked back.

It was no simple matter for Marvin Schick, a 40-year-old newcomer, to suddenly take the helm of an executive board whose longstanding members were wealthy old-timers, many of whom weren’t even observant and shared nothing of his worldview. But through sheer determination and the force of his winning personality, Dr. Schick employed his abundant personal charm and compelling salesmanship in equal parts, making the case that RJJ’s continuity depended on catering to the new generation of Orthodox families who represented the Jewish communal future.

Still, many board members were not prepared to go quietly into the night. The RJJ dinner had always been a ritzy affair held at the Plaza Hotel on the Upper East Side, replete with mixed dancing. When one board member insisted on a very elaborate flower arrangement to grace the dinner, Schick responded that on his watch, yeshivah money would no longer be squandered on such things. The member left the board in a huff, taking his financial support with him, but Marvin wasn’t fazed. At another meeting, he diplomatically but firmly gave notice that mixed dancing was now a thing of the past. A long-time board member objected, unrolling a piece of paper which read, “Minhag avoseinu b’yadeinu.” Marvin laughed, and after he and Mr. Bunim exchanged knowing glances, he simply moved the meeting along.

Beyond marshaling the support of RJJ’s lay leadership for his ambitious plans, Dr. Schick faced the daunting challenge of putting the school’s financial house in order. There were a slew of financial headaches to resolve, from unpaid real estate tax bills to fee disputes requiring arbitration to complications involving properties the school owned in different parts of the city.

Basic fiscal logic in this situation called for slashing expenditures, but his first official act as president was counterintuitive and quintessentially Marvin Schick: He made sure that all outstanding salary monies owed to the yeshivah’s past rebbeim were paid up and that they would receive pensions going forward. He went so far as to initiate a retroactive “pension” for the widow of one of RJJ’s great roshei yeshivah, Rav Yosef Nevenensky, who had passed away at a young age in 1967.

For the next 44 years, a monthly check would arrive in Rebbetzin Nevenensky’s mailbox. The money certainly helped, says her son Reb Chaim, but the check’s far greater meaning was that she hadn’t been forgotten after all these years. “It was a lifeline connecting her to the yeshivah where her husband had played such an important role,” says her son.

How did someone whose sole background was in academia and public policy rather than fundraising step into the breach to take on the overwhelming financial burden of new institutions? Rav Yosef Eichenstein, rosh yeshivah of RJJ Edison, says he was “a tremendous ba’al kishron, who grasped things very quickly and whose insight was uncanny. And when he didn’t know how to do something, he’d say, ‘Let’s just do it and we’ll figure it out.’ ”

For many people, starting a chinuch institution comes first and a philosophy of education only later, if at all. In Marvin Schick’s case, taking charge of RJJ was the vehicle for implementing his already fully formed views on chinuch and his deep desire to see every Jewish child thrive. Says Rabbi Eichenstein, “He was passionate about Torah education and that made him absolutely driven.” On a personal level, Rabbi Eichenstein relates, “his tzedakah was beyond comprehension. He didn’t even own his home, yet when someone he knew needed a down payment on a house, he wrote him a $10,000 check. He was always looking to be meitiv to other Yidden, whether he knew them or not. I never knew anyone else with such a desire for hatavah.”

Injustice truly pained him, and by Marvin’s standard, that included heavy-handedly extracting tuition from parents who couldn’t afford it. “He fought against that even if it was going to cost him,” notes Rabbi Eichenstein. “He could dress down a school balabos regarding the tuition issue even if it meant losing that person.”

What Taking Charge Means

By 1976, Schick was ready to begin rebuilding the new RJJ in earnest, with the launch of a boys’ elementary school in the expanding Jewish community on Staten Island. He felt that Rabbi Yaakov Feitman, then principal of a small kiruv school in Canarsie, was the man for the job, and after one brief interview he announced with characteristic aplomb, “Mazel tov! You’re the new menahel of RJJ.”

As Rabbi Feitman recalls it, Dr. Schick had firm ideas he wanted implemented in the nascent school: “He was extremely insistent — which I believe he got from Rav Aharon — that even the rebbeim of the youngest classes be talmidei chachamim, people who could uplift the students. Where they had gone to yeshivah didn’t matter, as long as they were devoted educators who wouldn’t hesitate to call up talmidim and check in on them, why they had missed class and so on. He may not have been a mechanech per se, but he understood kids very well, both little one and big ones.”

Next, he worked with Rav Shneur Kotler to lay the groundwork for a high-level mesivta and beis medrash, which opened in Edison in 1981. Yossi Stern recalls that “with Marvin, you had to be on your feet all the time. He was demanding because he was demanding of himself. It was all emes, all sincere and fair. He had no personal agenda — Klal Yisrael was his only agenda — and he showed me what it meant to have achrayus. Yet he never took all the achrayus on himself because he wanted to get others involved and share it with him.”

Schick brought together Rabbis Yaakov Busel and Yosef Eichenstein to lead the new yeshivah, which went on to establish itself in the top tier of American yeshivos, and at whose head the two remain until today. Rabbi Feitman remembers being a bit dubious of the shidduch, given their very different backgrounds, but, he says, “Marvin told me that they would be the perfect pair — and he was right.”

Rabbi Busel points out that although Dr. Schick had been the prime mover behind the yeshivah’s creation, he drew a clear line when it came to the school’s chinuch matters. “Marvin wanted to be the role model for the place of a balabos. When we started he told us he would be assuming a large portion of the financial responsibility, but that he wouldn’t mix into the chinuch at all,” says Rabbi Busel. “He was an opinionated person, and would make suggestions, but they really were just that.”

Yossi Stern adds that “da’as Torah was Marvin’s guiding light. He was very close with Reb Elya Svei, and once, when we were facing a decision about a certain property, Reb Elya came down on a Sunday morning to see the site firsthand, and Marvin was prepared to accept whatever Reb Elya would pasken.” It was the Philadelphia rosh yeshiva to whom he turned, too, regarding his later involvement with the Avi Chai Foundation.

In 1986, with the Edison yeshivah and the boys’ school both solidly established, RJJ took yet another step in building the Staten Island community, opening a girls’ elementary school in the borough. Then, in 1991, Dr. Schick pushed the RJJ board to make a bold move that truly showed the depth of his commitment to making Torah accessible to every Jewish child. The Jewish Foundation School (JFS), a coed, Modern Orthodox day school in Staten Island since the 1950s, was on the verge of bankruptcy, with the bank getting ready to foreclose.

The more religious students would have had no problem finding a place waiting for them in the existing RJJ schools. But most JFS kids came from nonobservant homes, and Marvin Schick was deeply concerned that if the school were to close its doors, some of the students would be lost to Yiddishkeit. And so, he decided that the only option was to assume the JFS debt, subsuming the school as a division of RJJ.

But he faced stiff pushback from both directions. The JFS people were concerned he’d change the school’s orientation. “Marvin was trying to help them despite themselves,” explains Paul Goldstein, a former JFS parent who has chaired its board for 30 years, “while their attitude was, ‘We’ll take your money, but don’t tell us what to do.’ They didn’t understand that Marvin wasn’t interested in interfering with internal school policy — he just wanted kids to get a Jewish education. At the same time, he was also getting grief from the RJJ board as to why they needed to get involved with a modern, coed school. But Marvin held his ground, saying there were 400 neshamos at stake. It was his courage in standing up to both sides that kept JFS alive.”

After absorbing nearly a million dollars of debt, Marvin worked with the JFS leadership to ensure its long-term solvency, and eventually helped the school complete a new building. “I can go through Teaneck and show you many dozens of graduates who wouldn’t be frum if not for JFS,” says Mr. Goldstein, “and without Marvin Schick there wouldn’t be a JFS. My son, a kollel avreich on Baltimore’s Yeshiva Lane, is an alumnus, as are others now in Lakewood, and they’re all attributable to Marvin.”

Dr. Schick simultaneously juggled the responsibilities of multiple institutions, but as his wife observed, “He saw the community, but never lost sight of the individual, and always got very upset at hearing that a child might be expelled or that a family couldn’t pay tuition.” During the shivah, a JFS parent who works in its financial office wrote to the family that when she took over the tuition collections, there were flash cards with notes on some families. “The card for one family, a nonreligious single mom with two girls read, ‘Do not ever ask for tuition, as per Marvin Schick.’

“When the older daughter was in eighth grade,” the woman continues, “I was shocked when her mother reached out to me to discuss the religious high school my daughter attends. She eventually enrolled her daughter there too, because, she said, since Dr. Schick put so much effort into giving her girls an elementary Jewish education, she should at least try to do the same for high school.”

It’s Their Birthright

Not content to be a serial founder of yeshivos, Marvin Schick got involved in every imaginable aspect of Jewish education, functioning over the decades as a sort of informal Secretary of Education for the Orthodox community. Three examples from across the Orthodox spectrum: When a businessman whom Marvin knew casually took the lead in opening a new boys’ elementary school in Lakewood, he received a call the next day: “I hear you’re opening a mosad; whatever you need, I’m here to help.” Dr. Schick called him regularly after that, “to encourage me on those inevitable frustrating days and say, ‘You can do more, don’t give up, don’t get tired.’ And he’d attend all my simchahs just to make me feel good about my involvement in chinuch,” says the founder of the school, which today has an enrollment of 1,400.

In 2005, Westchester Day School (WDS) sued the Village of Mamaroneck in federal court for zoning discrimination, and asked Dr. Schick to testify as an expert witness regarding the building needs of Jewish day schools. He prepared an expert report and testified at the trial — but refused to take any compensation. According to WDS attorney Stanley Bernstein, his testimony, based on having visited over 400 day schools nationwide, helped the school settle with the village for an unprecedented $4.5 million in damages.

“There isn’t a zoning board in the United States that isn’t aware of the ruling in this case,” Bernstein says. “Dr. Schick’s words won over the judge, whose oft-cited opinion speaks movingly about the importance of a religious education in America.”

That same year, Marvin produced a series of 12 ads in the Orthodox press addressing essential, and controversial, issues in yeshivah education, with the goal of sparking broad communal discussion and ultimately, change. These ads, intended as open letters to the frum community, conveyed his deep-felt belief that it was a distortion of Torah values to treat a child’s Jewish education as a consumer good to be paid for by parents regardless of their means, rather than as a birthright to be guaranteed by the community.

Million-Dollar Deal

Rabbi Yaakov Busel describes Marvin Schick as “a tremendously driven individual, always asking what he was going to do with this day, with this hour. How many other ehrliche Yidden would you find in their office on Erev Pesach, Erev Yom Kippur? But he was there, because things had to be taken care of. Marvin had this compelling need to fill every day with achievements.” Brooklyn attorney and RJJ board member Eli Feit says Dr. Schick was an anomaly in Jewish organizational life: “He didn’t have a big staff, just a single secretary, and he was terrible at delegating because when he needed something done, he just did it himself right away.”

For all of his drive and accomplishments, his daughters recall a playful father who took delight in everything they did. Shani Schick says her father “would always love it when we had friends over, kibbitzing with us, and showing a genuine interest in whatever we were doing.”

Adina Schick remembers returning home as an eight year old after visiting a classmate on Shabbos. “I related that my friend’s father had asked me what my father did and I said that I didn’t know but that he helped a lot of people. I had answered honestly based on what I knew of my father: that he spent his days helping others and emphasized doing the right thing because ‘it’s the right thing to do.’ ”

At an age when most other people would be preparing to retire, Marvin Schick undertook a capstone to a career spent making American chinuch blossom, through his involvement in the Avi Chai Foundation. Established by Wall Street investment manager Zalman C. Bernstein after his midlife embrace of Orthodoxy, the foundation’s philanthropic niche was day-school and yeshivah education, spurred on by the 1990 Jewish population survey’s sobering data on intermarriage and assimilation and Dr. Schick’s research findings about the powerful effect of a day-school education in creating knowledgeable and communally involved Jews. .

Over several decades as a senior adviser to the foundation, Dr. Schick facilitated Avi Chai ’s sponsorship of numerous programs benefiting yeshivah students to the tune of tens of millions of dollars, including programs that sent public school children to Orthodox camps in the hope they’d then transfer to day schools; the investment of millions in Jewish high school libraries; tuition vouchers to attract public school students to day schools; funding for Chinuch.org, the Torah Umesorah online database of teaching materials used by thousands worldwide; and support for improved instruction at schools for immigrant students.

But Marvin Schick’s crowning achievement at Avi Chai was the loan program he administered for expanding and improving day-school facilities across North America. Through this initiative, nearly 150 day schools and yeshivos, all of which he visited personally, received seven-figure interest-free loans for constructing new buildings. Recalling Marvin’s long years of activity with Avi Chai, founding trustee Arthur Fried becomes emotional, saying Dr. Schick “radiated vitality of mind, of speech, of the written word. He was a remarkable gift to the Jewish People and to humanity in general. I don’t know if there will ever be another like him.”

Marvin remained active on multiple fronts until the end, the fire of love for Jews and Torah that Rav Aharon had kindled so many decades earlier still burning brightly within. If ever that flame dimmed, all he had to do was to glance at his dining room wall, to the framed copy of handwritten notes the Rosh Yeshivah had made for a speech, a last message to Klal Yisrael about the transcendent importance of educating the next generation in Torah. Discovered by the Rebbetzin in his kapoteh after his petirah, they were notes for a message he never had a chance to deliver.

But Marvin Schick, his loyal torchbearer, did instead.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 812)

Oops! We could not locate your form.