Succah for Life

| September 14, 2021Why HaKadosh Baruch Hu uses succah as the litmus test to determine whether the nations of the world deserve reward

"I have a mitzvah kalah, an easy mitzvah, and its name is succah.” This is how HaKadosh Baruch Hu refers to the central mitzvah of this Yom Tov.

Yet in a piyut for Succos we learn that the mitzvah of succah is equivalent in value to all the mitzvos. The Toras Chaim explains (Avodah Zarah 3a) that although there are other mitzvos also said to be equivalent to the whole Torah, each of these other mitzvos involves certain disadvantages: Shabbos incurs a monetary cost because one must set his work aside; the techeiles in tzitzis is very expensive; milah is very painful. But the mitzvah of succah involves no difficulty, and this is why, when the nations of the world demand an opportunity to do mitzvos, Hashem chooses to test them with a succah.

It would seem that succah is indeed an easy mitzvah. The mitzvah itself requires no exertion — all a person has to do is enter the succah and sit down, and he has already fulfilled the mitzvah. But if we only knew how to extract the true value of this mitzvah, we’d be able to understand why HaKadosh Baruch Hu uses it as the litmus test to determine whether the nations of the world deserve reward for their deeds.

From my teacher and grandfather, the gaon Rav Yitzchak Yedidya Frankel ztz”l, chief rabbi of Tel Aviv, I learned several lessons we can glean from the mitzvah of succah:

Just for Now

The succah is a temporary dwelling. A person must remember that his entire life on this earth is temporary, whether his daily life is one of wealth or poverty, comfort or constraint, whether he lives in a palace or a dark cellar. The mitzvah to dwell in the succah lasts seven days, symbolizing the seven decades of human life (as the pasuk says, “Yemei shenoseinu shiv’im shanah”). Whoever forgets this and thinks he is here forever is sadly mistaken. He is in for a bitter disappointment.

Immune to Impurity

A succah may not be constructed of items that are mekabel tumah, materials that absorb impurity. It isn’t enough that the item is clean and pure in its current state; we must make sure that tumah cannot possibly even be transferred to it in the future. There are people who haven’t sinned all their lives — not because their souls are pure but because they didn’t encounter opportunities to sin. A person must refine his nature to the point where even if he has the means and the opportunity to do evil, he will resist. (The Rambam teaches that a person has done complete teshuvah when he does not sin even though he could.) A human being should be a beautiful vessel that cannot hold tumah.

Privilege, Not Pain

The mitztaer is exempt from sitting in the succah. A person who finds it unpleasant and uncomfortable would do better to stay in the house. Similarly, a person who doesn’t feel proud to be a Jew doesn’t have to force himself to enter the succah of Judaism. There have been many times in our history that we were subjected to force by others, but on principle we don’t compel anyone to join the Jewish nation. The Jewish People has always been a small nation but has always prized its identity and doesn’t perceive Yiddishkeit as a painful, heavy burden but rather as a privilege worth its historical price of trial and sacrifice.

Not Too High, Not Too Low

A succah taller than 20 amos is invalid. Hashem doesn’t like arrogance; He loves to see us living lives of humility. “I dwell… with the crushed and humble in spirit,” He tells us. Unwarranted pride is passul. A person may have risen to a high rank, but he must not take credit, “for this is what you were created for.” And of course, a succah that is too low is also passul, for excessive humility is also inappropriate. Cultivate the tzelem Elokim that is imprinted upon you, don’t devalue it.

True to Our Origins Material that has completely changed its form is invalid for the mitzvah of succah. For example, paper and cardboard cannot be used for the sechach even though they are made from wood that grew out of the ground. Their original form is no longer recognizable. A person who presents himself as something other than what he truly is, whose exterior belies his interior, is passul. Before his death, Yannai HaMelech told his wife not to fear the Perushim or the Tzedukim, but rather the hypocrites who do evil like Zimri and seek the reward of the righteous Pinchas. One may improve, deepen, or expand his mitzvah observance, but the foundations remain unchanged and eternal. There is no new Judaism.

Unknowable

If there is more sunlight than shade in the succah, it is invalid. One must aspire to perfection and strive to reach ever-higher levels, but we shouldn’t be pretentious and think we know all the secrets of the universe. No matter how advanced man’s knowledge may be, he must always know that the shade is greater than the light, that vastly more remains unknown. “Toras Hashem temimah,” the Kotzker Rebbe used to say, explaining that even after all the Tannaim, Amoraim, Geonim, Rishonim, and Acharonim spent their lives plumbing its depths, the Torah is still whole and perfect, sealed before us and untouched. The ultimate knowledge is knowing that we don’t know.

Shelter from Above

The sechach must not be too thick, either. One must be able to see the sky through it. The essence of the succah lies not in the four walls of this temporary shelter but rather in our exposure to the Presence above us. When we sit in our succah, we experience an open invitation to “Lift your eyes on high, and see who created all this.” If you forget this and hide under a roof in your own arba amos, never looking up at what is above you, you forfeit the primary lesson of the Yom Tov. The essence of the succah is the knowledge that there is Someone who shelters you and that your safety and security lie entirely in His hands.

For at root, this mitzvah is all about trust. Rabbeinu Bechaye highlights the fact that Bnei Yisrael’s wanderings in the Wilderness were meant to strengthen their trust in HaKadosh Baruch Hu. In his introduction to parshas Beshalach, he writes that every challenge the Jewish nation encountered in the Wilderness was a nisayon meant to increase their bitachon, which is the root of emunah. And he illustrates: “He split the sea before them as they passed through it, and not all at once…. When they came to Marah, the water that had been sweet became bitter, and by means of the branch of wood it was sweetened again…. Similarly, the mahn came down in sufficient amounts for each day, rather than a supply for many days…. All these matters were meant to test them, in order to anchor the trait of bitachon in their psyches… for the middah of bitachon is a central principle, and it is the foundation of Torah and mitzvos.”

This, too, was the reason that Bnei Yisrael dwelled in actual succahs during their stay in the Wilderness, according to the opinion of Rabi Akiva. And it’s the reason why we still have this mitzvah today.

In this same vein, the Maharsha explains the pasuk in Tehillim, “All Your mitzvos are emunah.” He says, “This means that all the mitzvos are included in the first mitzvah that we heard from the Mouth of G-d, which is the mitzvah to believe in Him. The prophet Chavakkuk crystallized this in the words, ‘And a tzaddik shall live by his emunah.’ ” The mitzvah of emunah, which includes trust in Hashem, is the foundation of all 613 mitzvos — a tangible demonstration that we believe in our Creator and trust in Him. And the mitzvah of succah is a week-long exercise in that faith and trust.

As we enter the succah and make good on that faith, we pray that HaKadosh Baruch Hu spread over us His succas shalom, and envelop us in His succah of mercy, life, and peace.

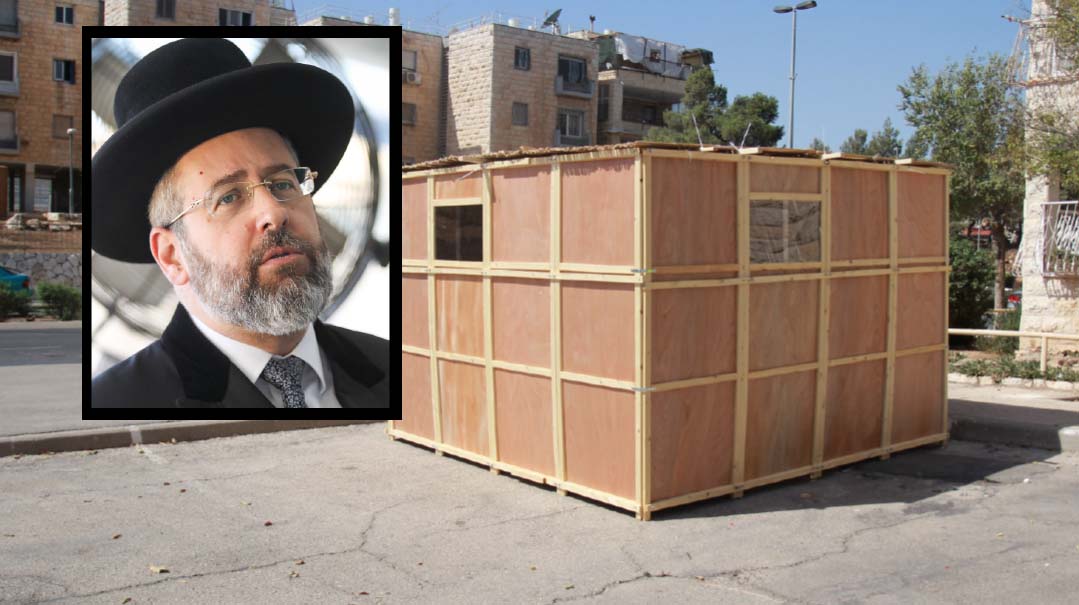

Rav David Lau is the Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Israel. He is the son of former chief rabbi, Rav Yisrael Meir Lau.

Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 878.

Oops! We could not locate your form.