Shadow Defenders

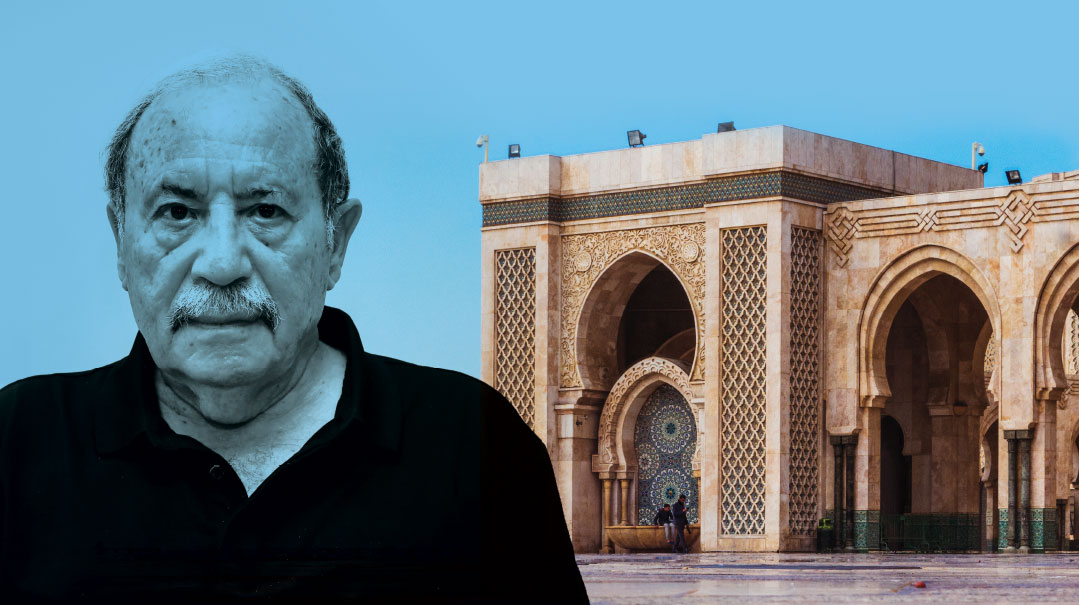

| November 25, 2020The secret squad trained to rescue Morocco's Jews

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, personal archives

Winter 1954. The reports coming out of French-ruled Morocco were making Israel’s security people lose sleep. There had already been two bloody pogroms in this North African country since the founding of the Jewish State in 1948, and while the French were officially Jewish protectors and permitted Jewish Agency activity and even a level of aliyah, if the country would declare independence and their French protectors pulled out, the Jews would likely find themselves in grave danger.

The Jewish communities were already living under hardship — businesses regularly paid “protection money” to local thugs, theft and arson of Jewish property was rampant, and mysterious disappearances of teenage girls were not unusual. About 70,000 Jews had already fled — many of them wealthy businessmen who escaped with nothing. And now, with independence on the horizon and the feared ascent of the radical Istiqlal party to power — the strings of which were being pulled by the Jew-hating Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser — the Israelis knew they had to act fast for the 200,000 Jews still in Morocco.

This was a job for the long arm of the Mossad.

As it happened, the Moroccan Jewish communities themselves were frightened of the departure of the French, and many young people would be ready to help the Mossad in its secret underground initiatives to protect the local Jews and help them emigrate. It wouldn’t be easy though, or glorious. There would be arrests, torture, and death at the hands of the hostile Islamic elements that sought to ferret out and destroy Israel’s protective arm.

October 1955. Mossad chief Isser Harel got the green light from Ben Gurion and began enlisting Mossad agents to operate in France, which had joint security interests with Israel. That month, seven Mossad agents landed in Morocco, led by Shlomo Yechezkeli and supported by former Haganah members Itzik Bar and Yona Zevin, and Etzel member Chaggai Lev.

The cover stories of these operatives were created to make their true identities difficult to track. One was allegedly a businessman from a European country who marketed spare parts for tractors. Another had an illness and needed the Moroccan climate to heal. And in typical Mossad fashion, each agent was taken back to the country of his “origin” in order to familiarize him with such banal things as the elementary school he supposedly attended and the grocery store on the block where he lived.

The first local recruit was a 20-year-old fellow named Meir (Michel) Knafo, who at the time was working as a manager for a Jewish hotelier in Casablanca. The Mossad team was looking for a local person to head the volunteers, and when Shlomo Yechezkeli strode into the elegant hotel lobby, he’d already done his research. Kfano was born in 1935 in Casablanca, attended the Jewish Alliance school, was active in the Habonim Zionist youth movement, and wasn’t shy about professing his love for the Jewish state.

It’s been 65 years, but Meir Knafo will never forget the meeting that changed his life. “Yechezkeli told me they’d heard about me, and that they were looking for someone local to head a squad they’d be setting up to protect the local population against both spontaneous and planned attacks,” he told Mishpacha. “And I really did have a big advantage. Many of the hotel guests were police and security officers from other cities, and I kept my ears open and was able to collect a lot of valuable information.”

During the meeting, Yechezkeli presented Knafo with a basic outline of the community protection plan. “He didn’t say an extra word, and at the end of the meeting he told me to think about whether I wanted to join. I answered him on the spot, ‘I don’t need to think. My answer is yes.’ He said to me, ‘If so, we can get to work.’ ”

Two days later, Knafo was invited to an apartment where Yechezkeli was waiting. On a small table covered with a towel was a Tanach, a folded flag, and a pistol.

“With one hand on the Tanach and the other on the pistol, I was sworn to dedicate my life to the organization,” Knafo says. (For Knafo, that would be the beginning of a decades-long career in facilitating security and aliyah for Jews trapped in Arab lands.)

At the end of the short ceremony, Knafo was given the code name “Morris,” received a communication device through which he could contact his handlers, and was instructed in how to recruit other team members.

“We had code names for everything,” Knafo says. “For example, if I had to meet Shlomo, I would call him and say, ‘Come for coffee to Madeline,’ which meant come for a meeting at the post office, where there were lots of people and we could talk without attracting attention.”

It was the opening volley for the establishment of the “Misgeret,” the Mossad’s underground operation in Morocco. There were three main divisions in the Misgeret: Gonen, which served as the operations arm in protecting the Jewish communities, Makhelah, which worked to bring Moroccan Jews secretly to Israel, and Modi’in, which activated an expansive network of sources in Morocco and beyond, fed in no small amount by local police who “sang” in exchange for payment.

Gonen was headed by Meir Knafo. “It was really the nucleus of all of the Misgeret’s activities,” he explains. “At first we worked primarily in Casablanca, which had 80,000 Jews, the largest Jewish concentration in the country, and within a few months we expanded out to all of Morocco.”

Initially, Knafo’s job was to recruit people to make up the security squads in each city. But in order to avoid being identified, he only reached out to those he didn’t know personally — and all these new recruits knew about him was that his name was “Morris.” Conditions for joining were clear: Each potential agent had to be young, healthy, speak Arabic at mother-tongue level, be a supporter of Israel, and be willing to take part in underground activity to help his Jewish brethren.

The Mossad had set up an intelligence network in France during the years that there was close security cooperation between France and Israel, and had direct access to French officials who worked in Morocco until the country declared its independence in 1956. Through these ties, the emissaries in Casablanca knew who to bribe in order to obtain inside information usually leaked from the Moroccan secret police.

Knafo got working plans from Shlomo Yechezkeli: Establish seven squads, each of which would have seven to ten members. Knafo managed all the teams, but they didn’t know about each other, or even who he was, for that matter. When he’d meet the squad commanders, he wore a long jalabiya and kept his face covered. “There was complete compartmentalization between the members,” Knafo recalls, “so that if one would be arrested, he’d know nothing about all the rest.”

Throughout the region, a number of weapons caches were created — the main one located in Knafo’s hotel, and another in a Jewish barbershop in Mellah.

One of the most well-known recruits at the time was a young Israeli woman named Yehudit Yechezkeli, a former Palmach volunteer and kindergarten teacher in one of the immigrant maabarot, sent by the Jewish Agency to set up a preschool in Casablanca. Her position became pivotal, as one of her teddy bears with a hollowed-out belly became a means of transfer of false papers, explosives, and correspondence between squad members.

Chaviv Abutboul owned a gym in Marrakech, which served as a training center for the Gonen agents after he was recruited. He eventually led his own squad, under Knafo’s direction.

Jack Azulai, a resident of the capital city of Rabat, had been studying law when he was recruited, but when the French regime left, taking with them the clerks in the government offices, thousands of local young people were quickly trained for various government jobs.

Azulai was placed in the Moroccan Agriculture Ministry, and part of his job entailed negotiating deals to sell tracts of forests to merchants who cut down the trees for construction which were exported out of Morocco.

“When the Mossad located me, I really didn’t understand what I could do to help,” Azulai remembers. But Mossad agents had checked comprehensively into his job and discovered that when a deal was set in motion, Azulai had to go to court with the stamps of the Interior and Finance Ministries to affirm the deals and the prices, and then to issue a payment slip.

“These two stamps helped the Mossad extensively,” Azulai says, although even decades later, he refuses to say what the stamps were used for. He does share that “lots of things were done that helped the Mossad, both in protecting the communities and in smuggling out Jews.”

Azulai’s year-long service in the Misgeret was suddenly upended one Friday night. “We were in the middle of the meal, when my handler came to our home and told me that I’d been ‘burned’ and that I needed to be taken to a hideaway. After I left, a team came to ‘cleanse’ my room of incriminating evidence. My parents were very alarmed because they knew nothing of my activities.”

In March 1956, Morocco declared independence, the French pulled out, and — as the Israeli security forces feared — the rise of the nationalist Istiqlal party, together with anti-Jewish incitement because of their treasonous desire to make aliyah, meant the Jews were not safe. Officially, when King Mohammed V returned from exile to lead the new independent country, he was more than happy to serve as the Jews’ protector. Very soon, though, he succumbed to the pressures of the Istiqlal and the vehemently anti-Jewish Arab nationals, who — in joint cooperation with Syrian and Egyptian agents — had planned a series of attacks.

Much of Knafo’s Mossad work in the early days of Moroccan independence involved securing events where a large number of Jews would be in attendance. He remembers a concert by renowned Moroccan singer David Buzaglo. After getting word that the Arab nationals were plotting an attack at the event, Knafo and his staff secured the shul by putting snipers on nearby roofs and deploying cells of fighters all around.

Another time, according to intelligence information Knafu received from the Mossad, there was an organized plan to harm the Jewish community in Casablanca by Algerian underground members who were also striving to gain independence for their country, which borders Morocco. The plan was straightforward: The Algerian underground would carry out a massive terror attack against the Jewish community, and would thus gain exposure for its cause.

‘Their interest was to be in the headlines,” Knafo explains. “They knew that if they killed Jews, that made headlines. Killing Muslims wouldn’t generate that kind of exposure.”

Although Knafo and his squad had armed themselves from their secret cache and prepared for a preemptive counterattack, neither wound up taking place. In the end, the Moroccan police also got wind of the plan, and when Knafo and his team arrived, they were surprised to discover secret police patrolling the streets where the attack was supposed to take place.

“We waited there for a few hours and nothing happened,” he says. “The next day we found out that the Algerians had canceled their operation because they saw police patrolling the area.”

The weakened status of the Jews created another terrifying trend: Often, girls from the Jewish community were abducted by local sheikhs with a lot of money and power, and the families were helpless to stop it.

After one such abduction by a senior police official, Jack Azulai was called up to tackle the travesty. “Everyone was afraid of that officer,” Azulai recalls, “and the family didn’t have enough power or influence to fight him.”

The abducted Jewish girls were usually held under heavy guard, and were only allowed outside under close supervision by one of the family members. “After a week of surveillance,” Azulai says, “we detected the times when the escort was weak. A few of us came, neutralized the escort, and freed the abducted girl. Then we took her to a hideaway known as a ‘cooler apartment’ — a house meant to hide agents who’d been exposed or Jews who needed immediate rescue. Within a day we prepared her a forged passport, and two days later she was in France. It was only at that point that we conveyed a message to the family that their daughter was out of Morocco.”

Knafo’s own squad in Casablanca handled more than a dozen such cases.

Meanwhile, all Jewish Agency personnel were expelled from Morocco, and an order was given not to issue passports to local Jews, meaning they couldn’t even travel to neighboring France.

“This led to panic in the community,” Knafo says. “Until then, the French had protected them, but after independence, they were vulnerable to attacks, and yet they couldn’t leave.”

At the time, there were a number of Jewish Agency transit camps where thousands of families who had already left their homes were waiting for their registration to come through in order to leave the country.

“But once the orders came to close the borders,” Knafu related, “mounted police surrounded the camps and didn’t let anyone in or out.”

The next order came two days later: All holders of Israeli passports (that would include many underground activists and Israeli Mossad operators) were instructed to leave the country within ten days. Anyone caught with involvement in secret aliyah would be imprisoned.

At this point, Zalman Shragai, who headed the aliyah department of the Jewish Agency and was a leader in bringing tens of thousands of North African Jews to Israel in the state’s few years of existence, realized that illegal aliyah was totally out of his purview — and so he turned to Mossad chief Isser Harel. But when Harel initially formed the security squads, he never thought they’d also wind up being involved in illegal aliyah as well.

Harel, undaunted, made a secret visit to Morocco to examine the progress of the agents in preparing sea and land routes through which to smuggle the Jews. He toured the coasts with the commanders of the Misgeret in order to locate spots where they could smuggle Jews onto boats without arousing the suspicion of the naval patrols.

A few local agents were sent for smuggling training in France, and others were even sent to Israel. Among them were Meir Knafo and George Vaknin (who would later become head of neurosurgery in Tel Aviv’s Ichilov Hospital). They left Morocco for France using Moroccan passports, and once in France, received foreign passports to fly to Israel.

Upon arrival to Israel, the Moroccan group was sent to a naval base, where they underwent a month of grueling training. “We learned how to swim in all types of ocean conditions, how to move boats without an engine, how to steer ships through emergency situations, and other maneuvers we’d need.”

Knafo, who at the time had a young son at home and was raising three adopted nieces whose parents were killed in an earthquake, was appointed commander of the smuggling squad.

That meant forging passports, concealing olim in cargo trucks and moving them by land to the Spanish enclaves that shared a border with Morocco, bribing Moroccan officials at seaports, and enlisting the British authorities who controlled Gibraltar and the French who still controlled Algeria.

At their peak, about a year after the ban went into effect, a truck left for Spain almost every night with dozens of Jews on board. Sometimes, the escapees were caught and sent back, their leaders imprisoned. Those who succeeded in escaping were sent to transit camps set up by the Mossad in Spain and France, and were eventually sent to Israel either by plane or ship.

There were also groups that were smuggled through official border crossings with forged passports, thanks to Mossad agent Shalom Weiss, the agency’s primary forger. When they came to the Marseilles layover, the Jews would return the passports which were sent back to Morocco, altered slightly, and then used for another group of illegal immigrants.

A watershed moment in the naval smuggling was the sinking of the ship Egoz. The ship was used to smuggle Jews from a northern Moroccan beach across the strait to Gibraltar. It had already made 12 trips back and forth, but on the night of January 10, 1961, tragedy struck and the Egoz sank at sea, apparently having hit a sandbank.

The losses were substantial and shocking: 44 olim, half of them little children. Only 22 bodies were recovered, buried in the Jewish cemetery in the Moroccan coastal town of El-Chusiema. (After three decades of negotiation with Morocco, the bodies were exhumed and reburied in Israel.)

Publication of the story had two opposite effects: On one hand, international pressure eventually led to a secret treaty that would mean a massive exodus, but the immediate result in Morocco was a wave of hostility against the Jews. They were accused of treason, which became grounds for ferreting out and persecuting the underground activists. Over the next year, the underground network in Morocco would be totally liquidated.

Yet even after the Egoz sank, as long as there were still activists around, the Mossad didn’t give up. It rented a large ship named Kokus, with a capacity for 250 people, which was supposed to smuggle Jews who had supposedly been holding a wedding ceremony on the beach. But before the ship could make its maiden voyage, the wave of arrests began.

“A night before, I was still on the beach for the final preparations of the Kokus,” says Knafo. “I came home at 4:00 in the morning. Four hours later I was arrested.”

It was 7:00 in the morning, and Mrs. Rachel Knafo picked up the telephone.

“Is Meir home?” a voice asked. “I’m a member of the squad in Fez and I need to speak to him,” the caller said.

Mrs. Knafo was a clever woman. When the anonymous speaker didn’t offer the prearranged code word, she guessed he was a Moroccan security officer, and quickly woke her husband, who’d just crawled into bed after returning from the coast.

Meir grabbed a passport and packet of cash, parted from his wife, and ran down the stairs. As he emerged from the building, he met a childhood friend who worked for the Moroccan secret police. The policeman was wearing civilian clothes, and he looked happy to see his old friend, Michel Knafo. Meir, for his part, realized he was being followed.

“Michel, how are you?” the security man asked. “We haven’t seen each other for years!” Knafo returned his friendly greeting, and after making small talk, the man asked his friend, “Do you know a guy called Meir? I was told he lives in this building.” Knafo shrugged and answered that he did not. “I came here for some dental work,” he said, “and I must hurry home.” He knew that the man wanted to arrest “Meir,” but had no clue that Meir and Michel was the same person.

Knafo ran across the street and looked for a taxi to take him to the “cooler” apartment, a hideaway for agents who were “burned.” Meanwhile though, the agent had gone to a nearby café, and when he asked one of the sidewalk diners if they knew where Meir lived, he pointed to the man across the street trying to flag down a cab.

Meir was arrested by his childhood friend, who apologized profusely. “Look, I’m really sorry about this, but I’m just doing my job,” he told Knafo, who knew all too well what could happen to a policeman who didn’t follow instructions — it was rumored that some found their end in the graveyard behind the police station.

Handcuffed and on the way to the station, it became clear that the policeman didn’t even know why he was sent to arrest his friend. “They told me to arrest you because you killed an Arab woman in a car accident,” he replied. Knafo was quiet. He understood the significance of this fabricated story and knew that he was in for very difficult days ahead.

At the police station in Casablanca, Knafo was handed over to investigators from the Meknes police, notorious for their cruelty. Within a few hours, he was on the way to the interrogation center in Meknes, prepared for the worst.

Knafo was fingered when two Mossad operatives in Fez hadn’t timed a certain operation precisely. They were arrested and tortured for a few days straight, until they broke. Fortunately for the Mossad agents, they didn’t know much about the activities on a national level, and knew only the commander of the Mossad activities in Fez, a mathematics professor who was a respected figure in the city. They gave over his name, and he was also arrested. The professor was also tortured, but loyal to his colleagues, he gave nothing away and didn’t disclose the names of any underground members. Until they used their game-changing weapon against him: They brought in his wife and threatened to murder her before his eyes if he didn’t give over the information about the underground leaders. At that moment, he broke down and gave over all the information he had. The results were disastrous: Five activists were arrested, including commander Meir Knafo.

Two of the detainees, Raphael Vaknin and Marcel Rouimi, were tortured to death in an effort to extract information from them about the Mossad network in Morocco.

Another person who was arrested was a well-connected municipal worker named Shimon Korcos. “They hung me from my hands for many hours,” he told Mishpacha. “Finally they transferred me to the prison in Meknes, where I learned for the first time the real name of Meir Knafo.”

Due to his senior position, Korcus was released from prison after a few days and returned to his municipal job. “Some of my Arab friends apologized that they couldn’t help me when I was incarcerated. They were afraid they’d be accused of abetting the Zionists,” Korcus says.

According to Knafo, the interrogators wanted one thing: to know the names of the Israeli Mossad agents operating in Morocco, where the weapons were hidden, and what the smuggling routes were. “Based on the questions they asked, I understood that they knew that I was the commander and that I was one of the few who were in touch with the Mossad agents in Morocco.”

For the next two months, Knafo was subject to unspeakable tortures. “I got electric shocks, they stuck my head into putrid water, they tied me to a bench and left me for long nights without sleep. During the easier days, the torture concluded with hanging me from my hands. Other days, they’d tie me to a wheel, which caused my muscles to tear and left me broken and in excruciating pain.

“Throughout the days of interrogations,” Knafo continues, “the interrogators repeated the same questions: Who are your superiors, what’s your route for taking the Jews out, where are the weapons hidden, and who is funding the operations? If they got a name from someone through other interrogations, they asked about him, for example, ‘Who is Joe? What is his job? Where does he live?’ Sometimes I recognized names of activists but I didn’t say a word.”

After two months in prison, Knafo’s condition was dire. His shoulder muscles were torn and he had hemorrhages all over his body. The Mossad people, who constantly tracked his situation through local sources, sent a message to headquarters in Israel that Knafo’s condition was deteriorating, and that he’d likely die of the torture, as did some of his comrades.

Following international pressure, Knafo was sent to the hospital in Meknes, where he fell into a coma. The attending doctor announced that he was “as good as dead,” but somehow he recovered enough to be transferred to a cell with others on death row in the Sidi Sid prison in Meknes. The prison was actually an underground dungeon, and his sentence was fast in coming: 60 years.

Knafo was depressed. Shattered. A shell of his former self. Underground in a smelly hole with no hope on the horizon.

One morning he woke up and thought he was hallucinating. From the street above his cell he heard the muted sounds of prayer, but it sounded like both verses from the Koran and pesukim of Tehillim.

Knafo asked what was going on and the guard replied that King Mohammed V had died. In each city, the residents gathered to weep over the loss — Jews and Muslims alike.

Mohammed V had been a revered king who had brought independence to the Moroccans. He tried to protect the Jews as well, but was no match for the opposition Istiqlal party. For Knafo, this was the worst news ever: The death of the king meant his fate was left in the hands of the secret service.

“Two burly detectives yanked me out of my cell and dragged me to a corner under the stairs,” he recalls. “One of them pulled out a pistol and said, ‘The king is dead. There is no one to protect you. Tell me right now who the Mossad people are and if not, we’ll kill you.’ I said Shema Yisrael, and they said to me, ‘If you don’t talk in five minutes, we’re killing you right here.’

“The detectives were stunned when I replied, ‘You can kill me but you and your families will be assassinated — there is someone who will do it for me.’

“During the long interrogations,” he explains, “there were times when I would doze off. They thought I was sleeping, but I heard parts of their casual conversation about their wives and children. Now I repeated the names of their children to let them think we knew a lot about them. A few minutes later they returned me to my cell and didn’t do anything to me.”

Shushan Purim of 1961 is considered for many Moroccan Jews the day when their dismal situation began to turn around. And the ones who felt it most were the 20 underground operatives being held in prisons around the country. On this day, Hassan II was crowned king of Morocco, after the sudden death of his father, Mohammed V.

Hassan II continued his father’s path in his fair treatment of the Jews, and he also despised Israel’s nemesis, President Nasser of Egypt. During the first year of his reign, the king expelled many of the Egyptian agents stationed in the kingdom.

The clash was inevitable: The Egyptian secret police came up with a plot to assassinate the king and install a ruler who would see eye to eye with Egyptian demands. The Egyptian secret service didn’t imagine that the agents of the Israeli Mossad were onto them, but the Mossad, who got wind of the plot, had another problem: how to convey this shocking information to Morocco, and how to ask for the deserved remuneration — the release of agents and perhaps even an approval for aliyah for Morocco’s Jews.

They decided the person to convey the information was General Mohammed Ofakir, the head of Morocco’s secret services and the man closest to the king. “To get to him, the Mossad people reached out to a close childhood friend of Ofakir, a wealthy Jew named Eli Turgeman,” says Knafo.

The Mossad discovered that the two of them had grown up in the Tafilalt region, and while Turgeman’s family was well off, the Ofakir family was destitute – and throughout their childhood, General Ofakir ate supper in the Turgeman home. The Mossad now asked Turgeman to set up a meeting with Ofakir and give him the information they’d garnered. When King Hassan II heard about the plot from his confidant Ofakir, he was skeptical about the veracity of the information — but he agreed that if there would be signs of an attempt on his life at the place and time that were noted, he would assess the information that Israel had conveyed and then decide if Morocco would release the prisoners.

It was a summer Friday, and as per his weekly habit, Hassan II left his palace in Rabat for the nearby plaza, where residents of the city would come to see the king and wave to him. The king would bless them before the Friday prayers and then return to the palace. Today though, no one besides the king, Ofakir, and a few soldiers from an elite unit knew about the fact that on the regal white steed sat a lookalike of the king, and not Hassan II.

When the “king” came out on his horse, there was a ripple of movement in the crowd. The king’s soldiers had discovered the assassins getting into position for the crucial shot. The information that Israel had given over turned out to be correct.

“That day,” Knafo says, “80 Egyptian agents were arrested in Casablanca. It led to a virtual end in ties between the two nations.”

After Morocco discovered that the information from Israel was accurate, the king had to keep his word. “But a blanket release of Jewish prisoners would have caused a revolt,” says Knafo. “So instead, they called us out, gave us everything they’d taken from us upon our arrest, and told us we had four days’ furlough.”

Like the other prisoners, Knafo headed home, from where he made contact with the Mossad, who smuggled him — and the others and their families — across the border to Spain in a cargo truck.

And it wasn’t just the Mossad agents that made it The Great Escape

out. The tenuously positive relationship between King Hassan II and Israel, together with an outpouring of international sympathy after the Egoz drowning disaster, laid the ground for Operation Yachin, a secret agreement under which King Hassan II agreed to accept a per-head bounty of 50 dollars for every Jew who emigrated from Morocco. A total of four million dollars was raised for 80,000 Jews (another 40,000 came after 1967), most of whom came to Israel to join the tens of thousands who had already made aliyah in the previous waves, and together, they comprised a 250,000-strong community — the largest aliyah from a Muslim country.

Meanwhile, Meir Knafo, who arrived in Israel with his family, didn’t take a break for the next six decades. From the shores of Eretz Yisrael, he remained a point man in the continued Moroccan aliyah. After the 1967 Six Day War, he was put in charge of Libyan aliyah by the Jewish Agency, and over the years the often secret aliyah and absorption of Iranian, Polish, Romanian, and Soviet Jews, plus the clandestine immigration of the remaining Lebanese Jews during the First Lebanon War, and the smuggling of Ethiopian and Sudanese Jews before the major airlift operations. Today, while he’s left his intelligence work to the younger set, he’s often a guest lecturer in schools and colleges, is the author of several books, and heads both the Israel Intelligence Commemoration Center and the North African Underground and Prisoners of Zion Commemoration Center.

Over 60 years later, not too many remember, or even know about, the role the Mossad operatives played in this decade-long drama. But Meir Knafo remembers, and is grateful that he can still tell the story.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 837)

Oops! We could not locate your form.