Secrets of the Deep

Is that a Nazi U-Boat submerged off the coast of Argentina?

Photos: Abel Batsi

A

man tightens ropes on a ship belonging to the Argentine coast guard. It’s a sunny day and in the background, the Atlantic Ocean stretches into the distance, a blue vastness.

The camera records as the man dons a bulky diving helmet, part of a pressurized suit used in deep sea dives, and drops into the water. A powerful flashlight beam lances the gloom of the deep. Out of the darkness looms a rusty metal skeleton, clearly the remains of a boat.

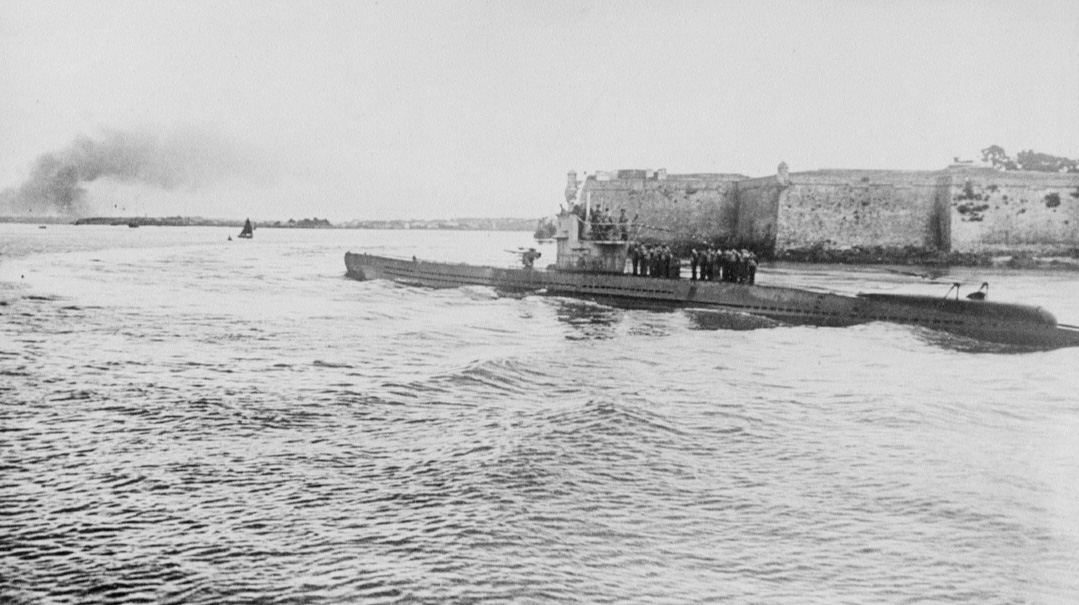

Then out of the spindly wreckage, emerges a long structure — a submarine’s periscope. While the oceans are littered with the ghostly wreckage of once-proud ships, this is something else. What would an old submarine be doing in the waters off the shores of Buenos Aires?

The grainy footage of the dive that aired recently in Argentina drew widespread interest, but there was one man who wasn’t surprised by the finding.

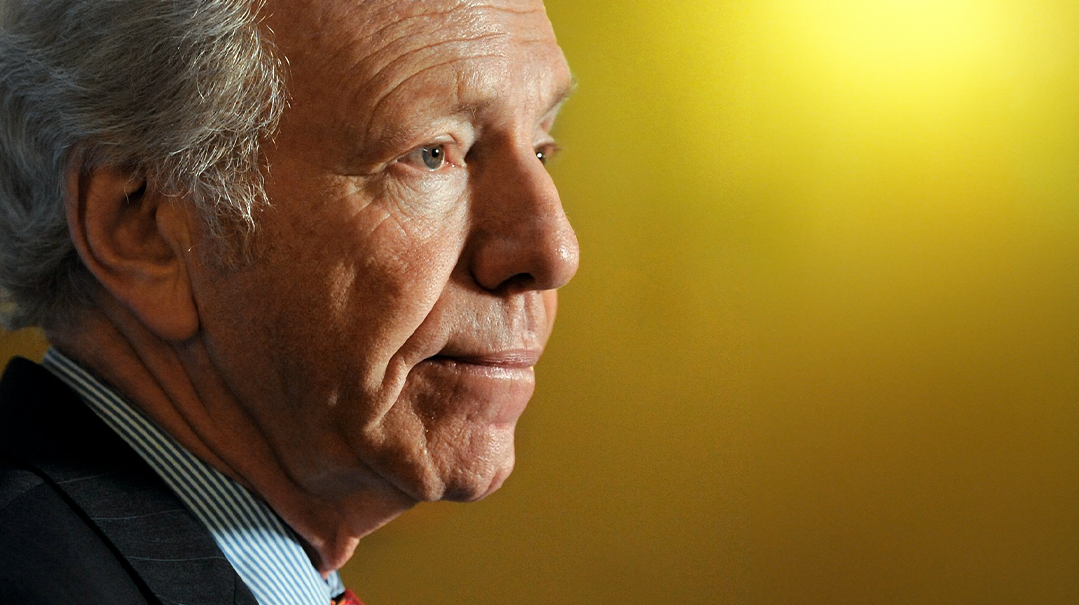

Journalist and researcher Abel Basti, the man in charge of the underwater expedition, is convinced that the mysterious craft is none other than a German U-boat. He’s spent decades building the case that the dirty secret of cooperation between South America’s right-wing regimes and the Nazis is dirtier than suspected. The evidence, he claims, suggests that the war criminals such as Eichmann and Mengele who found refuge in Latin America were not simply isolated cases, but part of a massive operation to aid fleeing Nazis.

Such an operation — including the landing of a U-boat — would have required the collaboration of the South American governments of the day and possibly even the approval of the United States, which until this day considers the region of its southern neighbors as its own backyard.

Straying into far murkier waters, Basti contends that the evidence points to something darker still: that Adolf Hitler himself arrived off the Argentine coast in one of these submarines.

While experts fiercely reject that conclusion, and the identification of the hulk as a U-boat isn’t conclusive so far, there’s no doubt of one thing: Abel Basti’s long campaign to highlight the secrets of the deep is politically sensitive.

Even today, the Argentinean government refuses to unseal the records on the country’s wartime past and for good reason: These facts have always been a thorn in the side of the Peronist party — which currently governs Argentina with a leftist bias — as they are new proof of the well-known pro-fascist origins of the legendary leader Juan Perón.

ABANDON SHIP Two views of the conical object that experts suspect is the sub’s periscope.

Missing Link

Abel Basti is nothing if not confident. Talking to Mishpacha from his home in Bariloche — an Argentinean city that has long attracted German immigrants — the 66-year-old journalist explains what led him to finance, out of his own pocket, a nautical expedition he called Eslabón Perdido (“Missing Link”), off the shores of Argentina, to find Nazi submarines.

“My assumption that there had to be a submarine there was based on different sources,” explains Basti. “Not only is there declassified documentation, but there are also records of complaints from local villagers. Even the newspapers of the time, in 1945, gave coverage to landings in the area.”

The Eslabón Perdido researchers encountered a fisherman who said he always had problems when casting nets in a certain area, and claimed there was something there, underwater. He passed the coordinates along to the investigators. Basti and his team, based on the rumors they had collected, the documents they had analyzed, and this testimony, decided to explore this location for any trace of a German submarine.

The investigation group began combing the beaches for any remains. They then applied to local authorities for a license to dive, and the resulting seabed survey produced eight hours of footage, including that of the ship.

“We found this hull, which is very large and was not on the nautical charts,” Basti says.

It also did not appear in a navigation book reporting every hull known in that part of the South Atlantic. The 80-meter-long sunken hulk had dimensions comparable to a U-Boat like the U-166, sunk off the coast of the United States in 1942. These vessels could carry a crew of 50 to 70.

Basti ordered that the find be subjected to two expert analyses. The first, certified by Juan Martín Canevaro, the current president of the Professional Council of Naval Engineering of Argentina, found only that the remains “did not belong to a ship” and that “it was possible” that it was a German submersible.

However, a lack of Argentine expertise on World War II ships made it impossible to achieve the certainty Basti sought. So he commissioned a second expert opinion, this time from the prestigious Liga Navale Italiana (Italian Naval League), an entity affiliated with the Italian Ministry of Defense, with extensive experience on World War II ships. There, Basti got what, internally, he already knew: confirmation that it was a German submarine from the Nazi era.

That U-boats operated in Argentine waters is well-established. In fact, two German submarines surrendered off the Argentine coast in 1945. The first, U530, on July 10, 1945; the second, U977, in August. Berlin had capitulated in May; this means that even after the war, Nazis were still circulating in international waters.

But Basti’s findings contradict the official government story. In the ’90s, faced with growing evidence of the presence of war criminals in the country, an entity called the “Commission for Clarification of Nazi Activities in Argentina” was created to investigate fugitives receiving asylum. The commission’s official report concluded that the only submarines that had arrived in the country had been the two surrenders mentioned.

If Basti’s findings are correct, and the vessel he discovered did indeed originate in Germany, the absence of any official records of a missing craft could indicate that it was on a secret mission, to spirit away an extremely high-ranking official.

The fact that the submarine was found relatively close to the coastal city of Necochea, in the province of Buenos Aires, at a depth of only 30 meters, is also suspicious. Was there official collusion involving the Argentine wartime government — one that that has been covered up ever since?

Abel Basti has spent decades convinced that the dirty secret of co-operation between South America’s right-wing regimes and the Nazis was dirtier than suspected: that the war criminals who found refuge in the south of the American continent were part of a planned operation that required the approval of the United States.

Cover-Up

How could such a significant wreck have been ignored in such shallow waters for more than 70 years? Why hadn’t the Argentine government located it?

Basti draws attention to some interesting developments that occurred in 1945: “The inhabitants of Necochea reported strange movements near the coast at that time. The police went to investigate and found tire tracks from trucks. They followed the trail and arrived at a ranch called Moromar. The person leading the investigation was a commissioner named Mariotti. When he went with five agents to try to enter the ranch, he was greeted at the gate by a group of armed foreigners who did not speak Spanish.

“Mariotti immediately returned to Necochea and asked for reinforcements and authority to enter the ranch,” Basti says. “However, the order came down from central headquarters to forget about it, not to do anything.”

Basti says he has learned from his research that this was all part of a pattern of Argentine government inaction on these matters. And the government maintains an official cover-up to this day, he says.

“To give you an idea: I located documents related to the landing of Nazis in Argentina and requested them from the Ministry of Defense. The ministry issued a ruling that these documents are considered ‘military secrets.’ I appealed twice, and on both occasions the Justice Ministry ratified that ruling. I mean, it’s not an issue for this government or for that particular government. The agreement to receive Nazis in Argentina has the status of a ‘state secret.’”

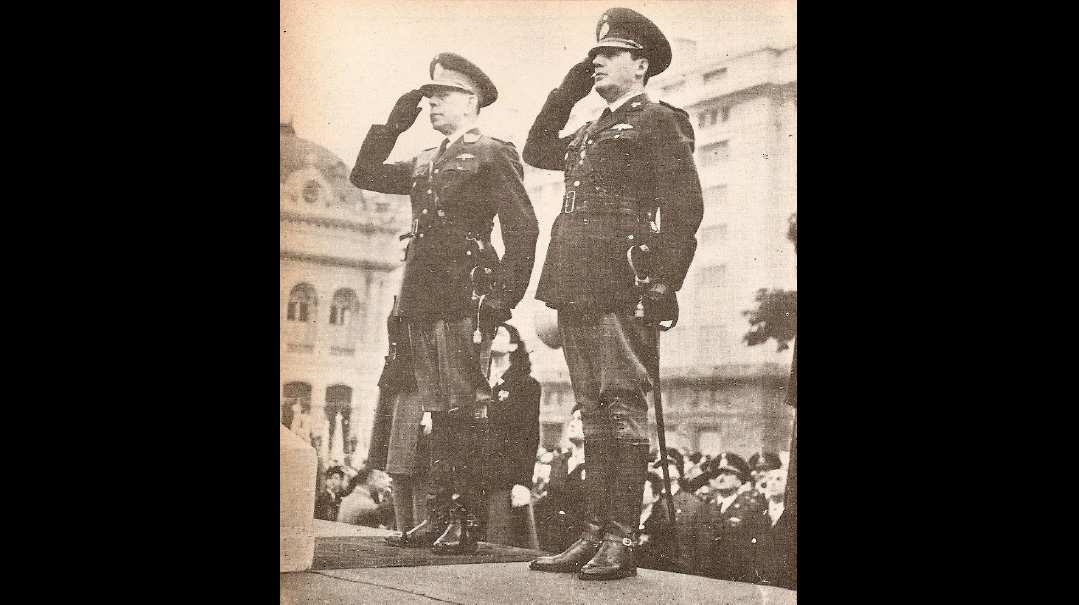

South American governments were more than willing to receive the Nazis. Argentina in 1945 was ruled by the military government of General Edelmiro Farrell, in which Juan Perón occupied a prominent role. A year later, Perón himself would become president, and he would shelter Nazi criminals during his ten years in power. Both Argentine leaders did not hide their admiration for the Nazis, and saw in the arrival of these war criminals an opportunity for Argentina’s technological advancement.

The existence of “ratlines” from Germany to South America is a matter of established historical record. Most of the governments in the area had strong military orientations (some were de facto governments, and others were elected, but all showed inclinations toward fascism). And that Argentina served as such a gateway should not be surprising, due to two factors: a longstanding economic relationship between Germany and Argentina, and the great political support that the Nazis had in that country.

“In Argentina there was an organized system, with people very close to the government, who facilitated the arrival of Nazi criminals in the country,” Ariel Gelblung, president of the Simon Wiesenthal Center for Latin America, tells Mishpacha. “The director of the migration office, Santiago Peralta, and Perón’s private secretary, Rodolfo Freude, were strongly identified with the Nazis and allowed their arrival in the country.”

While Gelblung avoided referring to Perón as a Nazi, he said the dictator’s “fascination with Mussolini’s fascism” was undeniable.

The Argentine military saw in Mussolini’s fascism a model to follow, and among those admirers was Juan Perón. In fact, in 1939 Perón was posted in Italy to serve as attaché to the command of the Tridentine Alpine Division. There he was able to study fascism close up, and even had two protocol meetings with Benito Mussolini himself. And according to official data, some 12,000 Germans arrived in Argentina between 1946 and 1952; although we can’t be sure that all of them were criminals, it is reasonable to assume that a high percentage of them were.

FASCISTS OF THE WORLD, UNITE Argentine leader and Nazi sympathizer Juan Peron

Arms Race

Even more unclear than the Argentine state’s role in the escapes is the potential involvement of the United States in the U-boat landing off Argentina.

At the end of World War II, it seemed only a matter of time before war broke out between the United States and the Soviet Union. Both the Americans and the Russians wanted to take advantage of German technological expertise and capabilities. It is known that both Allied and Soviet forces harbored Nazi war criminals at the end of the conflict. The two new superpowers offered immunity in exchange for information in areas as varied as medicine, nuclear energy, and rocket technology.

The Truman administration approved “Operation Paperclip” to bring more than 1,600 Nazi scientists and some 3,700 of their relatives under the custody of the US government. Among the beneficiaries of this operation were aerospace engineers Wernher von Braun and Kurt Debus, both loyal Nazis with experience in the Fuhrer’s arms development who were indispensable for NASA.

The Soviets were not far behind. With its “Operation Osoaviakhim,” the Red Army recruited more than 2,200 Nazi scientists, who, together with their families, totaled some 6,000 asylum seekers. Among those recruited by Stalin were Erich Apel, a colleague of von Braun’s in developing the V-2 rocket for the Nazis, the first long-range guided ballistic missile, and Ferdinand Brandner, a former SS officer who was instrumental in developing Soviet bomber aircraft.

However, not everyone received such special treatment. While some experts in particular areas such as atomic energy and aeronautics were utilized by the victorious powers, many others were only allowed entry into the country. They had to earn their livelihoods under new identities. Many people were later surprised to learn that their elderly neighbor who seemed so nice had in fact been a bloodthirsty war criminal.

In fact, it is known that in 1960, a certain “Ricardo Klement” returned home after his day working on the assembly line of the Mercedes Benz factory and, when he got off the bus as a simple citizen, he was kidnapped by two men. Ricardo Klement was none other than Adolf Eichmann, and those men were Mossad agents, who fulfilled the task of transferring the war criminal to trial in Israel.

A WW2 German U-boat

Devil’s Bargain

That Nazis came into Argentina after the war is uncontroversial. Abel Basti, though, believes the submarine landings prove something far more significant: that what happened in Argentina was not accidental, and that the South American nations could not voice opinions about it, because everything had been agreed to in advance between the Nazis and the Americans.

“At the end of the war there was great agreement between the Germans and the Americans,” Basti declares. “The Nazis were anti-Communists, and so were the Americans. There was an agreement to save the technology of the Nazis, so that it would not fall into the hands of the Soviets. In addition, the Americans controlled the air and water, so it would have been impossible for a single Nazi to arrive in Argentina without the approval of the United States. All the more so, that a fleet of submarines could cross the Atlantic without their permission.”

According to Basti’s investigations, the boats left from Norway, Spain, or the Canary Islands.

“It was a matter of convenience and mutual interests,” Basti explains. “The utilization of Nazis was government policy, within the framework of a strategic plan of the United States. But these recycled Nazis were also useful for local development, in technology, energy, and the war industry. To give you an idea, Argentina was the first Latin American country to develop a jet plane, at a time when only powers such as the United States or the Soviet Union were capable of this. That was possible only thanks to the Nazi engineers and pilots who arrived in large numbers in Argentina.”

Limited Scale

Not everyone is convinced that the Nazi escape plan was anything as monumental as Basti describes it. Dr. Danny Orbach is an expert in military history and professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He has researched the activities of the Third Reich in depth, and in his latest book, Fugitives: A History of Nazi Mercenaries During the Cold War, he focused particularly on the Nazis who were repurposed by the Americans and the Soviets.

“It was logical for the Nazis to seek refuge in South America, because in the mid-’40s there were extreme right-wing governments there that disliked the Communists,” Orbach tells Mishpacha. “In addition, they were developing countries hoping to import much-needed expertise. Hiring experts can be very expensive. By giving asylum to Nazi technicians, they could get the experts they needed for free. The same thing happened in Egypt or Syria.”

But Professor Orbach took strong issue with Abel Basti’s contention that the Nazis had hatched a massive escape plan in collaboration with South American regimes and possibly even Allied governments. The Israeli historian clarified that only in very specific cases did Nazis obtain pardons from the Allies.

“They had to be extremely useful technicians to be granted pardons, so the number was extremely small,” Orbach said.

And contrary to popular belief, the historian stressed that, of the Nazis who received asylum, the vast majority were not scientists, but officials of the intelligence services such as the SS or the Gestapo. The undeniably large numbers of Nazi criminals who arrived in South America came in a piecemeal, camouflaged way and not as part of an organic plan.

Basti’s theory, on the other hand, is that the Nazis arrived in Argentina in great waves as part of a scheme orchestrated by the United States. Although the existence of the submarines would seem to support the journalist’s version, Professor Orbach preferred not to comment on the recent discovery of the shipwreck, saying he needed more information before he could issue an opinion.

Flight of the Fuhrer

Abel Basti’s journey into the murky world of Nazi-South American ties began in 1994, when a team from the American television network ABC led an investigation in the city of San Carlos de Bariloche, in southern Argentina, under the assumption that SS Captain Erich Priebke was there.

Priebke had been convicted in absentia of war crimes in Italy for commanding the unit responsible for the 1944 Ardeatine massacre in Rome, in which 335 Italian civilians were killed in retaliation for a partisan attack.

After an arduous investigation, the journalists found him. For almost 50 years he had lived peacefully in the city under a false identity and worked in a local school. When Priebke acknowledged to the TV crew who he was and the material came to light, the city was besieged by media outlets from around the globe.

Abel Basti was then a correspondent for the DYN news agency assigned to the story. Since then, he has dedicated himself exclusively to tracking down war criminals harbored by Argentina, writing a dozen books on the subject.

His most controversial theory is that Adolf Hitler was among the refugees in that southern city. Even before the submarine was discovered, Basti was already well known for declaiming to anyone who wanted to hear that Hitler’s presence in Argentina was a proven thing, supported by documentation and testimonies. Now, after the discovery of the submarines, he insists that it is “verifiable in a logical way” that the dictator hid in Argentina.

“Let’s use reverse logic,” Basti says. “The Nazis who arrived in Argentina were very well known. They were officers of the highest rank, such as Adolf Eichmann, Josef Mengele, or Erich Priebke. All of them arrived only by boat, and didn’t even have cosmetic surgery. They changed their names and were given false documents, so their safety was already guaranteed when they arrived in the country.

“Now, if these criminals could arrive by boat on these shores, to bring in higher-ranking people who had greater exposure and who needed greater immunity, it only made sense to mobilize submarines. Logically, then, those who arrived in submarines held higher positions in the Nazi hierarchy than those who arrived by boat.

“Who was above Mengele? The head of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Goering, was in custody and later committed suicide. Hitler’s number two, Karl Dönitz, was imprisoned. The head of propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, and the head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler, had committed suicide. This is not my opinion, these are concrete facts. And who was left in the hierarchy?”

When I mention to Basti that his version contradicts the accepted history of Hitler taking his own life in his Berlin bunker, he dismisses this as “a grotesque and fabulous farce.” He launches into another thread.

“The Nazis wanted to instill the idea that Hitler had committed suicide,” Basti insists. “However, it is very easy to see what happened if you read the newspapers of the time. Immediately after the war, Stalin accused Spain of giving refuge to Hitler. Something which, by the way, was true. Keep in mind that Spain was ruled by the dictator Francisco Franco, an ally of the Reich.

“In addition, the successor German state, the Federal Republic, which was theoretically not Nazi, did not declare Hitler dead until 1956, and only under the ‘presumption of death.’ This is public. So Hitler was considered legally ‘alive’ until 1956. With the additional bit that, since he had allegedly committed suicide, there were no open legal processes against him. Consequently, there was no arrest warrant. That is, he could legally circulate as a free citizen.

“But, in addition, there is no proof of this alleged suicide. There are no bodies, no images, none of Hitler’s blood in the bunker. If one carefully investigates the testimonies of the witnesses, as I have done in several books, it is easy to see that they contradict each other. All there is, is a piece of bone supposedly from Hitler’s skull with a hole, something that is ridiculous, and which was later denied by American scientists. The version that they burned the bodies is also very unlikely, because incinerating two bodies in the open is absolutely impossible. It’s all too strange.

“Many say that believing Hitler escaped is a conspiracy theory,” he says. “But I think the biggest conspiracy theory is the one they concocted about the bunker.”

Basti argues that Argentina’s Patagonia region was a “natural” refuge for Hitler. But whether the Fuhrer actually settled there or not, it is clear that many Nazi war criminals in fact did. And this marks a chapter of history that the current Argentine establishment would prefer to ignore.

The ruling Justicialist Party, perhaps like no other political party in South America, has seen its ideology vacillate wildly over time. Under the umbrella of “Peronism,” Argentina has had military juntas, governments of the most liberal Peronist right, and feudal leaders in the provinces, also Peronist.

At this moment, Peronism has turned to the left, at least in rhetoric, and today the mythical leader Juan Perón (who died in 1974) is lionized as a defender of the workers. This discourse has penetrated deeply into the younger generation, to such an extent that many of the traditional left-wing parties have lost ground, with Peronism managing to co-opt a large part of their electorate. All of this has come about through a whitewashing of Juan Perón’s image. The Peronist march, sung in all party events, defines him as “the first worker,” and the images of him with his arms raised and a broad smile give no hint to his fascist past.

However, the historical record shows that Nazi Germany had excellent relations with the Argentinean government and acquired thousands of hectares in the south of the country. Patagonia is a vast and relatively unpopulated territory, and the local government offered absolute protection. Maybe Hitler didn’t live out his final years there, but many of his devoted followers clearly did.

Added to this was the absolute protection afforded by local governments. According to Basti’s version, after settling in Argentina, Hitler had the tranquility of being a refugee under the shelter of friendly governments: Farrell’s until 1946 and Juan Perón’s until the mid-’50s.

When Perón’s government fell in 1955, many Nazis left Argentina for other South American countries. The most favored destination was Paraguay, ruled by General Alfredo Stroessner, a de facto pro-Nazi president who controlled the country for more than 30 years. (Through fraudulent elections, he was reelected president seven times.) Basti’s version of events is that Hitler died in 1971 in Asunción del Paraguay.

Needless to say, this is flatly rejected by the academy, and Professor Orbach takes up the case.

“To say that Hitler escaped to Argentina makes no sense,” he says. “Hitler’s death has been accepted by the world’s leading historians and is documented. There is no doubt that he could not possibly have escaped. I have already heard these theories involving other such criminals as Martin Bormann, Hitler’s personal secretary. People say they have seen Bormann virtually everywhere in the world. But both Hitler and Bormann died in 1945. The bunker incident is not a theory, it is what really happened.”

Uncomfortable Truths

Researcher Abel Basti is now waiting for the German government to rule on his findings. As he explains, if the German state of Bavaria acknowledges that this vessel was under its flag, then, according to maritime law, it would be entitled to ownership. But if it denies involvement, Basti himself would become the owner of the boat . For the Argentinean, it is a “win-win situation”: If the Germans claim the ship, they will be proving the existence of clandestine trips. If they deny it, he will become the owner of a historical piece. He guesses that the second scenario is more likely.

But regardless of what happens in the future, the most uncomfortable aspect of this story is that, although there are differences in the number of pardoned, everyone agrees that there was systematic protection of many war criminals. Thousands, and perhaps tens of thousands, of people who held hierarchical positions behind the most heinous machinery of the last century were pardoned and even protected by the very same governments that had fought them.

“This is something that sounds ugly, but it’s absolutely normal,” says Professor Orbach. “It’s normal because, at that time, nobody could know if we were going to see a Third World War or not between the Americans and the Soviets. Today we know it didn’t happen. But at that time, people were sure that the conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union would lead to a new world war.

“The Americans knew very little about the Soviets and believed that they needed the experience and knowledge of the Germans to be prepared for war. It is very natural to prioritize confrontation with the enemies of the present over bringing justice to the enemies of the past, even in cases of terrible crimes. Even the Mossad, the Jewish state’s intelligence service, used Nazis for intelligence work. There was a lot of debate about it in Israel at the time. But in the ’60s, Israel had to deal with other enemies, not the Nazis, but the Arab states. I’m not saying it’s something nice, but it is something absolutely normal in history.”

Almost eight decades after the war ended, and even as a mysterious hulk in the depths of the Atlantic Ocean triggers renewed interest in vanished Nazis, the search for the war criminals goes on.

“We don’t know of anyone who is still alive,” says Ariel Gelblung of the Simon Wiesenthal Center for Latin America, “but it doesn’t mean we aren’t watching for them to show up. The search is never abandoned.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 944)

Oops! We could not locate your form.