Rules of the Jungle

Zebras, ostriches, and Jewish skeletons in a trek through Namibia

As told to Eliyahu Ackerman by Meir Alfasi

Photos: Meir Alfasi

Diamonds in the sand, the last standing shul, and a tombstone with a kosher l’Pesach engraving were just some of the treasures nature photographer Meir Alfasi hoped to discover on a trek through Namibia in southwest Africa. Surrounded by zebras, ostriches, termites, and malaria-carrying mosquitoes, would he find the Jewish skeletons he was looking for in the endless desert expanses of the emptiest country in the world?

I

n the cemetery at Swakopmund, a resort village on the western coast of Namibia, I’m looking for a Jewish tombstone with a kosher l’Pesach label.

It’s not a joke. But first, a little background on Swakopmund, which was founded in 1892 as the main harbor for the Imperial German colony in Namibia — formerly known as South West Africa. In this beachfront town, with picturesque homes that seem to have been transplanted from the Bavarian mountains and set down in the heart of southern Africa, you won’t find a lot of Europeans today, but many of the store marquis are still in German. Before Namibian independence from South Africa in 1990, many street names were in their original German, but that changed after the revolution, when, for example, the main street’s name was changed from Kaiser Wilhelm Strasse to Sam Nujoma Avenue, after the then-president who renamed the street after himself.

Notwithstanding Swakopmund’s European roots and multicultural history, I wanted to discover if there was a kernel of truth to an anecdote I’d heard about a Jewish family from Vilna who, at the beginning of the 20th century, ended up in a remote corner of Africa. The family did well in business, but due to a lack of Yiddishkeit in the region, the children grew up totally ignorant of their heritage. Before the family patriarch passed away, he requested that the family place Hebrew letters on his headstone, which he knew his own parents and grandparents had done. But despite their desire to fulfill their father’s will, his children were stumped: They had no idea what a Hebrew letter looked like. According the version of the story I’d heard, only the youngest son refused to give up the quest. He turned the house over from basement to attic until he found a Jewish text on a box of matzos, which he carefully copied onto the headstone: Kosher l’Pesach.

Knowing that I’m a nature photographer who’s always looking for new frontiers, a friend and historical researcher suggested I make the trip to Namibia. I’d have my fill of rhinos, ostriches, and rolling sand dunes stretching for miles, and maybe I’d even find the alleged grave.

I’d like to report that I quickly upped and packed my bags for Namibia, but really, I traveled to the offices of Salt of the Earth Ltd., a salt company in the town of Atlit near Haifa. That’s where I’d be able to find Ms. Jill Katz, the one responsible on behalf of the honorary Namibian consul in Israel for issuing entry visas to this exotic country.

Ms. Katz studied me skeptically, from my yarmulke, tzitzis and beard to the soles of my dusty shoes.

“And what would you like to do in Namibia?” she queried cautiously.

I told her that I’m a nature photographer, and I’d like to document rhinos and antelopes.

“And that’s it?”

I shrugged. “And if I’m able to find a kosher for Pesach gravesite, it will be a bonus.”

Will Tzvi Gorelick of Windhoek’s Hebrew Congregation be closing its rusted doors for the last time?

Time to Move On

Tzvi Gorelick opens the door of the Windhoek shul to a rusty squeak. A thick layer of dust covers the barred windows, while the heavy odor of wood furniture, old siddurim, and yellowing talleisim hangs in the air. Quite a bit of time has passed since this door had last been opened.

“The bars were installed during the Angola War, which began in 1975, in order to prevent hand grenades from being thrown inside,” Gorelick comments as he gropes for the light switch.

There isn’t a long history of the Jews in Namibia, but the small Jewish population in the capital city of Windhoek did play an important if minor role in the development of the country in the last century. (While the thought of African countries create all sorts of images in the mind’s eye, Windhoek is a modern city with spacious homes, shopping malls, and fancy office buildings, and even a Shoprite supermarket.)

This shul was built in 1925 by the Orthodox Windhoek Hebrew Congregation, and was accompanied by a Talmud Torah and a communal hall. On the wall in the anteroom hang black-and-white photographs of the leaders of the Windhoek Jewish community through the years. They look like businesspeople with warm Jewish hearts. Gorelick, the last gabbai of the shul, is another link in a chain — although he’s likely to be the final link.

“I still remember the days when the Talmud Torah had 150 students,” he tells me. “Today there are only 12 people who come to shul. I don’t know how much longer we’ll be able to keep the place open. We’ve been getting requests from people interested in buying the building.”

Tzvi Gorelick is the linchpin of the tiny Jewish community: He’s chazzan, gabbai, darshan, and baal korei; he’s in charge of operating the shul, organizes minyanim to say Kaddish, teaches Torah to anyone who is interested, and if there’s a request, can also prepare young boys for their bar mitzvah.

“During the peak times, there were about 500 Jews living in Namibia, most of them in Windhoek,” he says as we walk through the spacious adjoining yard.

There’s a pleasant breeze coming up from the Atlantic Ocean, and I envision kiddushim, bar mitzvahs, and weddings that once took place on these grounds.

“We were connected to the Jewish communities in South Africa, and rabbanim would come from there every so often to serve the community. There were extensive Jewish and Zionist activities, and while Namibia never played a prominent role on the Jewish map, there was a tranquil and pleasant Jewish life here.”

“And when did it all change?” I ask.

“The turning point was probably in 1965, when the national struggle began that ultimately led to Namibia’s independence in 1990. Many Jews preferred to leave, mostly to the established communities in South Africa. Those who remained did their best to watch over the younger generation, most of whom ultimately dispersed to different places around the world.”

“When’s the last time you celebrated a bar mitzvah here?” I ask.

“Long enough ago to forget how we throw the candies,” he admits, but then switches to a ray of hope for the future. “In recent years there’s been a steady trickle of Israeli tourists and hikers, and a few businesspeople who have settled here. Today, most of them aren’t in touch with the local community, but maybe in the future it will change.”

I see that one of the seats in the shul is elevated, as if on a pedestal.

Tzvi notices my look and explains: “This is where the ‘king’ sat,” he says.

The “king,” I soon learn, was a prominent local Jew named Harold Pupkewitz.

“Everyone in the country knew Pupkewitz,” Tzvi says, surprised that I’ve never heard of him.

It turns out Pupkewitz was a Namibian entrepreneur and member of the President’s Economic Advisory Council, director on the boards of several large companies, and president of a number of high-profile political and financial institutions.

“For decades,” says Tzvi, “he was the financial backbone of the community, and served as the honorary vice president of the shul. You should meet his daughter who lives not far from here.”

As he closes up, it’s hard for me to shake off the feeling that the squeaky iron gate symbolizes the end of the Jewish era in this corner of Africa.

“Who knows how many gilgulim this neshamah had to go through?” No Jew is too far away for Rabbi Yossi Rachimi

Personal Example

“My father’s life was like a flag for the Jews of Namibia,” says Merrill Beeri, Harold Pupkewitz’s daughter.

Wherever you go in these parts, you’ll run into mementos of him: Pupkewitz Motors, Pupkewitz Industries, Pupkewitz Brothers Co. and Pupkewitz Bank. There is even a university named for him. It seems like nothing in Namibia happened without Harold Pupkewitz being involved.

“My father was born in Vilna, but he hardly knew his father when he was a child, because he traveled to distant Namibia and established a business, building oxcarts,” Mrs. Beeri relates.

The family was finally reunited in 1925, after the father had saved enough money to pay for passage for his wife and three children. They arrived in Namibia when European settlement had hardly even begun there.

“My father studied at a local university, and through diligence and honesty, he became the biggest businessman in the country — yet he always remained a very proud, warm Jew. He never sufficed with generous donations for the needs of the community — he served as the vice president of the community and made sure to be present in the shul in order to serve as a personal example.”

Pupkewitz passed away in 2012 at the age of 96, but until his final years, he still worked in his office six days a week.

“He would call himself a ‘real workaholic,’ — until it came to Shabbos,” Merrill says. “On that day he refused to work, no matter what.”

Never Too Late

In Windhoek, the concept of traffic jams doesn’t exist, the streets are clean and orderly, the air is fresh and clear — if a bit on the warm side, and the urban scenery is the opposite of crowded and stifling.

We travel with Rabbi Yossi Rachimi, the Chabad shaliach who came to the country last year. “There’s work here both with the veteran community, most of whom are assimilated, and with Jewish tourists and businesspeople who come here for the desert adventure and for the diamond trade,” he relates.

As we travel, we pass the huge complex that houses the Chinese embassy. Its massive size and the number of satellite dishes on its roof generate lots of mysterious speculation. Some claim that it’s the ground control station for the Chinese space program. When the first Chinese astronauts make their way to Mars, they will get their orders through Namibia. Others connect the huge size of the embassy to the strategic uranium mine located nearby, which is the largest of its kind in the world.

Either way, the Americans didn’t remain far behind, and established a huge embassy complex of their own, most of which is hidden and secret. So Namibia has two huge embassies of leading superpowers — not bad for a country whose entire population is less than 2.5 million.

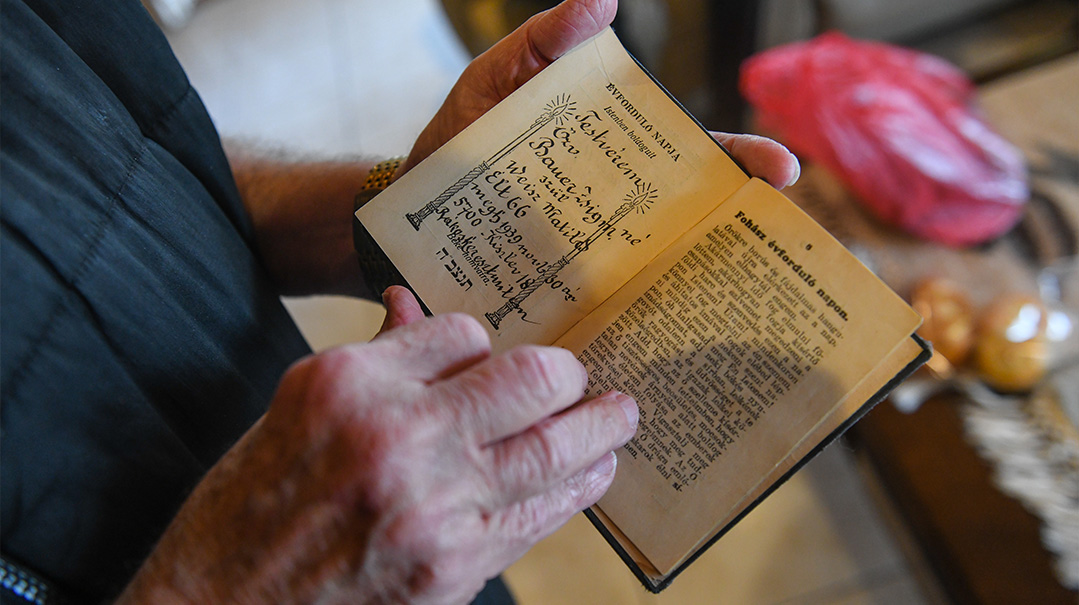

We stop off at the home of George, an elderly Jewish man to whom Reb Yossi has established a connection. George serves as the honorary consul for Hungary in Namibia. While he’s married to a non-Jewish woman and it’s doubtful if he ever had a bris, Reb Yossi insists that he put on tefillin.

“As an honorary consul, you know how important it is to represent your heritage with dignity,” the energetic Chabadnik says. “We are all Hashem’s consuls in this world.”

George smiles, and then out of an ancient siddur written in a Hungarian transliteration, he says the words of Shema Yisrael with intensity.

“Who knows how many gilgulim this neshamah had to go through until it merited to put on tefillin, here in this remote corner of the world?” Reb Yossi says as we leave.

Jungle Book

Namibia is an empty land.

While there are only 2.5 million people living in this country, which spans one million square kilometers, the demographic balance is somewhat rounded out by four-legged creatures such as lions, leopards, baboons, zebras, giraffe, elephants, and rhinoceroses.

Now we’re heading north toward Etosha Park, near the border with Angola. The word “park” is a bit deceiving, because it’s actually a nature preserve that spans an area larger than New Jersey, and the only rules that reign here are the rules of the jungle.

“Don’t kindle fires; don’t feed animals; don’t drive at high speeds,” the guards warn us at the entrance.

“What’s the most dangerous creature in the park?” I ask.

“The mosquito, of course,” the guard replies without thinking twice. “You have no idea how many people die each year from malaria. I hope you didn’t forget to be inoculated, and that you’re carrying anti-malaria pills.”

(We didn’t forget. Before leaving home, we took a vaccine against the type A liver infection, typhus, and yellow fever. Likewise, we were warned not to drink tap water, even in the hotel.)

Late in the afternoon, we take up our position near the lake. It’s an ideal spot for the camera to capture the animals that come for their evening drink.

The hierarchy of the animal kingdom is wondrous. First the lions come. Only when they finish, do the others join the party. The zebras stay close to the giraffes, as the long necks of the latter help them identify predators from afar. If the zebra sees the giraffe breaking into a run, it realizes it better get a move on as well.

We also see huge mounds of termites.

“Millions of termites have worked for 70 years to erect this structure,” the guide says, pointing to a mound that is as high as a three-story building. “They work in absolute order, and each one knows what his role is. That is how they construct their structure, grain by grain.”

At night, I suddenly remembered the mission I had come for. I called Tzvi Gorelick.

“Where can we find the kosher for Pesach kever?” I ask.

He thinks for a moment. “Go to Swakopmund,” he advises. “You won’t find any living Jews there, but there is a Jewish cemetery that is pretty well preserved. Maybe you’ll find what you’re looking for there.”

Germany’s First Victims

You can see signs of Namibia’s past on its roads: They are organized and well-maintained, in keeping of the German way of doing things, but we drive on the left side, as they do in Britain.

We travel southwest, passing rolling empty expanses as we head for the southern coast. For most of the year, this open coastline is enveloped in an eerie mist and fog, and remains of partially buried boats peeking through the sand are silent testimonies to the bitter fates of those who traveled by sea and met their ends in this remote location. It’s no wonder they call it “Skeleton Coast.”

But the skeletons are not only found on the coast of Namibia, but also in its past.

In 1883, a 21-year-old German explorer named Heinrich Vogelsang dropped anchor in this small inlet. When he came ashore, he found nothing but sunbaked rocks and sand dunes. There was no drinking water, and only one very narrow path leading further inland. Vogelsang met the local leader of the Nama tribe and purchased the inlet from him, as well as the land around it, for 100 British pounds and 200 guns. Later, he persuaded the German statesman Otto von Bismarck to recognize the entire piece of land as a German colony.

The ties between Germans and the locals began on the left foot, and went downhill from there.

The Germans dreamed of a global empire, while the locals struggled under their rule. In 1904, a rebellion erupted and the German Schutztruppe military unit was sent to suppress it with extreme brutality.

“Only uncompromising rigidity will lead to success,” the governor of the German colony declared. “In 15 years, not much will be left for the children, but we must keep this a secret, otherwise their uprising will be inevitable.”

The commander of the German forces, Lothar von Trotha, however, rejected the criticism of his troops’ brutality. “It is impossible to wage a humane war against those who are inhuman,” he explained. “I intend to destroy the rebellious tribes in rivers of blood and rivers of gold.” In a letter to the German headquarters, Von Trotha wrote, “It is better that the nation disappears completely, lest it contaminate our soldiers.”

Later, a destruction order was issued against the Nama people, the first time that this concept of genocide appeared in German dialogue.

The Germans carried out their plans assiduously. Half of the tribe members were slaughtered by guns and artillery. The rest were banished to the desert, to makeshift camps in which they were enslaved, tortured, or killed by disease. The German governor of Namibia at the time was a fellow named Heinrich Goering, whose son Hermann Goering would be a central figure in the Third Reich.

One way to inject life into Death Valley

Off Limits

I squint in the bright light and study the sand closely. Maybe I’ll be lucky enough to come across a diamond?

Twenty years after the Germans arrived in Namibia, a laborer putting down iron tracks near Luderitz noticed a sparkle in the ground. It was the beginning of the diamond rush that brought thousands of new settlers from Europe to Namibia. The Germans called the area “Sperrgebiet” (the prohibited area) and closed it to outsiders.

The Sperrgebiet spans an area that is bigger than the entire State of Israel, and to this day it’s closed to visitors without advance reservations. Surprisingly, the only settled area in the Sperrgebiet zone, which is designated for the employees of the mines who work there, is called “Rosh Pinah.”

We didn’t get a permit to visit Rosh Pinah, but on our way southward, we came across another settlement with an Israeli name. About 70 kilometers south of Windhoek, the sign on the road informed us that we were getting to the city of “Rehoboth” (Rechovot).

It was a bit surprising, because I actually live in Rechovot, and until that moment, I was sure that it was about 9,500 kilometers from Namibia.

“The first ones to establish the city were mixed-race people who came from South Africa,” explains Peter, a local guide. “They walked for a long time in the desert, without water — and only here were they able to dig a water well. Being believing people, they perused the Bible, and found that after Isaac was able to dig his third well, he called the place “Rechovot” and so that’s what they named their settlement.”

While we can’t get into Rosh Pinah, we are able to go into Luderitz, the last point along the coast before the prohibited area. The influence of the German settlers is still quite evident. On the main street, there are taverns selling German beer, and the passersby greet each other with “Guten Abend.”

Some of the Germans in the city even supported the Nazis during World War II, and in contrast to the Nazis of Berlin, the ones in Luderitz never tasted the shame of defeat and never raised a white flag. So it happened that for many years, the local neo-Nazis would post big signs each year to mark the birthday of the Führer, and even took out similar ads in the media. This repulsive custom was only stopped after a determined legal battle waged by none other than the “king,” Harold Pupkewitz.

Near the city is “Death Valley,” an area with huge sand dunes and patches of ancient Joshua trees. We settled down for the night out in the open, near a lake whose waters were as red as blood, reminiscent of the makkos in Egypt. Not surprisingly, we were assaulted that night by a swarm of locusts. We would encounter makkas arov later, in Etosha Park. We were thankfully spared the plague of lice.

Early in the morning, as the orange African sun rose over the eastern horizon, I enveloped myself in a tallis, to the stunned gazes of the ostriches, who must have taken their heads out of the sand for the occasion. This is one way of infusing life into the valley of death.

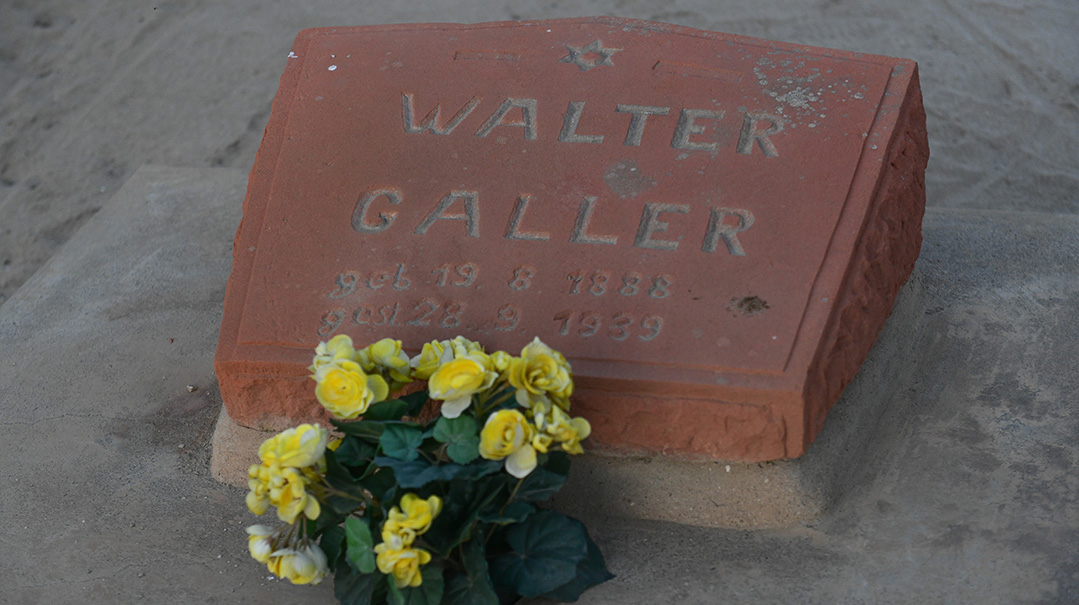

The chiseled-off tombstone. Walter Galler’s non-Jewish family did their best to memorialize his abandoned heritage

Kosher L’Pesach

Silence envelopes the Jewish cemetery in Swakopmund. What stands out is the large number of children and babies buried there. One headstone belongs to a youngster named Moshe Charney, who passed away at the age of 18. According to the vague inscription, we can only imagine which adventures he managed to experience in his short life: “You wanted to go to Eretz Yisrael, but death met you first, and like Moshe Rabbeinu, you remained in the desert.”

I came to Swakopmund to complete the last piece of my journey.

There is no Jewish present in this place, there is only a Jewish past. Although the Jewish settlement in Namibia began during the German rule, its primary growth came later, after World War I, when Germany lost its assets in Namibia. The land was then given as a mandate by the League of Nations to South Africa.

As a result, a new wave of Jewish immigration began, but the reasons it never expanded are scattered all over this cemetery: In the early years of the community, life in Namibia was difficult and the health care services were minimal. Jews needed a very good reason to want to come here — or they had to be extremely desperate.

Only in the 1950s and 1960s did the community reach a certain state of establishment. But then, Namibia was drawn into the apartheid and discrimination battles and the United Nations announced the end of the South African mandate, but Pretoria chose to ignore the order and continued to hold on to Namibia for another 20 years, into the period of the wars with neighboring nations such as Angola. When the battles came to an end at the beginning of the 1990s, most of the Jews had already left the country — and that was the end of the tiny community of Swakopmund as well.

And there, in the dimness, I found the gravesite I was looking for. It turns out, though that the “hashgachah” had been removed. Someone has erased the famous inscription.

A short inquiry revealed the story behind the strange headstone:

Walter Galler, a Jew from a Galician family, landed in Namibia as a young man. Due to the circumstances of the times, he married a non-Jewish woman of German extraction. While Galler was not very connected to the Jewish community, when it came to Pesach — it doesn’t matter how far a Jew strays — he always wanted to obtain a bit of matzah, and that’s what Walter used to do each year. When he passed away at age 51 in 1939, his gentile widow wanted to acknowledge his Jewish heritage on his headstone. In addition to the Magen David symbol, she cut out the only Hebrew lettering that she knew — the kosher l’Pesach symbol on one of the matzah packages that her husband received. She asked a local stonemason to etch these words onto his headstone — but because he didn’t know Hebrew, he etched the words onto the matzeivah backward.

In time, a Jewish journalist who noticed the unusual lettering wrote about it in the newspaper he worked for and the story spread. One of Galler’s sons, however, felt it wasn’t respectful to his father, so he took a chisel and erased the words on the headstone.

As the sun set, I stood at the graveside of Walter ben Aharon and said a chapter of Tehillim for the aliyah of this distant soul, as I pondered the vicissitudes of Jewish destiny.

The story I’d heard before setting out to Namibia was not completely accurate, but was also not totally detached from the African reality of things. In distant African regions, there were Jews who paid a very serious spiritual price for their detachment, while others went out of their way to strengthen their communities despite the difficulties. During my journey, I saw testaments to both.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 939)

Oops! We could not locate your form.