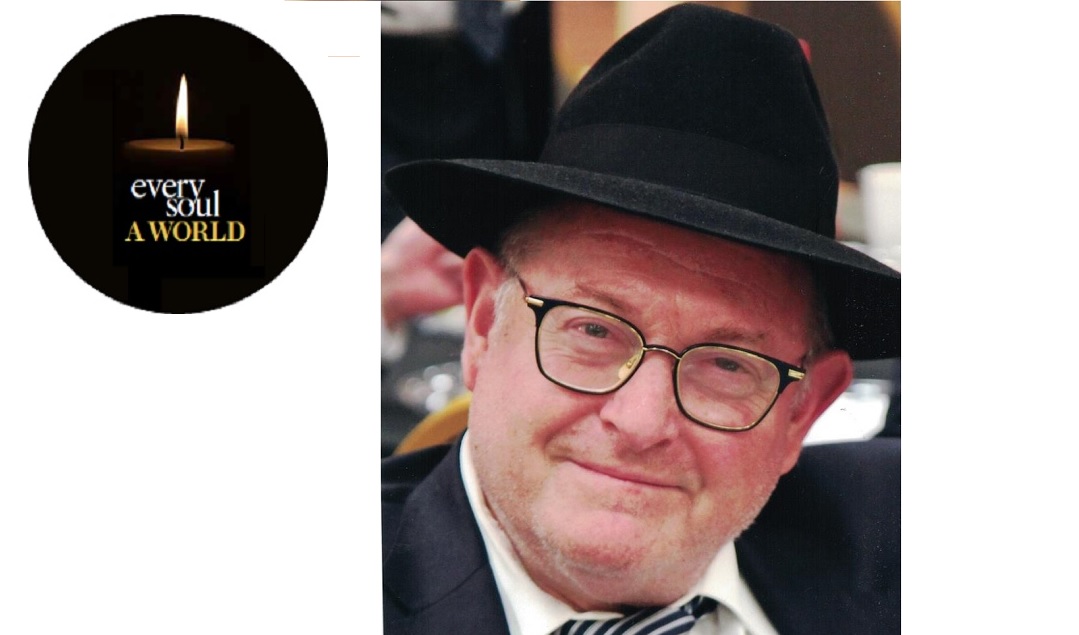

Rabbi Yeshayahu Heber

After undergoing a kidney transplant himself, Rabbi Heber saw up close the enormous suffering experienced by dialysis patients — and stepped in to make a drastic change

A

decade ago, Rabbi Heber was a Jerusalem cheder principal and a maggid shiur in the Nesivos Chochmah yeshivah in the Bayit Vegan neighborhood). His entire day revolved around chinuch — he loved learning, teaching, talking to bochurim and helping them work through their issues. But then, at age 45, he experienced renal failure and found himself on the receiving end of a kidney from a friend.

After undergoing a kidney transplant himself, Rabbi Heber saw up close the enormous suffering experienced by dialysis patients swinging back and forth between hope and despair, as opportunities for a transplant seem concrete but then disappear.

During the long hours he spent hooked up to a dialysis machine until a kidney transplant gave him a new lease on life, Rabbi Heber met many other patients suffering from kidney disease, but what pushed him to take action was the case of Pinchas Turgeman, a 19-year-old boy from Kiryat Arba whose condition had deteriorated to a critical level. Rabbi Heber took the initiative to look for a compatible donor and in fact found one, but Pinchas passed away before all the bureaucratic procedures could be completed. With his passing, the Turgemans were left childless — Pinchas’s one older brother had been killed in the course of his army service.

“This shook me to the core,” Rabbi Heber recalled in an interview to Mishpacha in 2018. “His father told me he sacrificed two sons, one on the altar of the Land of Israel and the other on the altar of Israeli bureaucracy.

“Even if a donor is found,” Rabbi Heber continued, “under the current medical system it might be months before the transplant can be performed, and many patients can’t survive that wait. I decided then that I would do everything in my power to expedite the bureaucratic process.”

During that first year, he arranged four transplants; the number has since grown to about 120 transplants per year. In the last decade, Rabbi Heber was responsible for saving the lives of over 600 people.

“People heard what happened to Pinchas, and soon I began receiving calls from patients and doctors who were seeking my help to obtain kidneys. After consulting with Rav Elyashiv, I started dedicating most of my day to these efforts, even cutting down my yeshivah hours. But more recently, I began to feel I just didn’t have the energy to continue pursuing these efforts. I went to speak to Rav Steinman, who had been my mentor and rebbi since my youth, and he told me that I wasn’t allowed to stop. That gave me the strength to continue, especially during the past year which was a real setback for our activities.”

Rabbi Heber was intimately involved in every step of the process — helping donors make a decision to undergo the operation, coordinating between the various transplant centers, and undergoing the testing and confirmation of compatibility that must be completed before a transplant can take place.

His goal was to shorten the waiting list for kidney transplants to zero waiting time, and the progress he made toward that goal has been applauded by people from all sectors of the population, triggering a synergistic response and widening the circle of lifesaving donors.

The donors come from all sectors of the population. Most are shomer mitzvos although the desire to perform this act of giving has burgeoned among nonreligious Israelis as well. It all happens on an entirely volunteer basis stemming only from a strong desire to do a special mitzvah whose only earthly profit is the pleasure of knowing that due to one’s altruism a fellow Jew who stood at death’s door has returned to the land of the living.

“We don’t convince anyone to donate a kidney,” Rabbi Heber told Mishpacha. “The decision to donate a kidney must come from a genuine desire on the part of the donor. Our job is to publicize the need for kidney transplants, to make people aware of the plight of dialysis patients, to provide professional information about the process of donating a kidney and the risks involved, and to publicize the stories of kidney donors and their donations.”

How did Rabbi Heber convince someone to give up a kidney? “We publish advertisements in the newspapers, and the response is significant. In general, we take the most tragic cases that come to our attention — such as a mother of eight children who is in urgent need of a kidney — and advertise them. These notices elicit a wave of interest, and after we find a suitable donor for the specific case that was advertised, we tell the other people who contacted about other patients in need.”

Rabbi Heber said the organization’s very first kidney donation came through Mishpacha, from an A. M. Amitz story about a mother of a large family who was in need of a new kidney.

Mishpacha's Rabbi Moshe Grylak was a friend and neighbor of Rabbi Heber, and davened mincha with him every day for years. Rabbi Grylak relates how he was always moved by Rabbi Heber's stories of the latest donor and patient shidduchim.

I can’t help but envy him as well for having merited to literally be mechayeh meisim. He glowed with happiness when he told his fellow mispallelim that kidney patient Ploni ben Plonis whom we’d been davening for was doing well following a transplant and had left his hospital bed on his own two feet. We heard moving stories of donors who gave a kidney after an inner battle with their fear of the invasive surgical procedure. He shared stories too of families that refuse to allow a loved one to give up a kidney, of families that hesitate and of families that warmly support a decision by their wife and mother for example to donate a kidney. It was always both heart-stirring and spiritually uplifting to hear these stories of heroism in fulfillment of Hashem’s will.

One time he came to Minchah extremely excited having just received a phone call from Germany. A Christian woman had read about his organization and wished to donate one of her kidneys to a Jewish person in need which she meant as an act of atonement for the crimes of her grandfather who had been active in service to the Nazi regime. After consulting with gedolei Torah he’d decided to grant the woman the opportunity she requested. Every day before or after Minchah we listened avidly to the latest installment of this unusual story. Eventually Rabbi Heber told us how the German woman had arrived in Israel about the warm reception she was given how excited she was to make this very real physical contribution to the Jewish People and how the transplant saved the life of a very sick young woman.

For all that I never was privileged to meet him, I am grieving deeply for Rabbi Avraham Yeshayahu Heber z”l.

I’ve always been fascinated by transplantation — especially how a living person can give of their body to help save another.

My husband and I had our blood drawn in Denver, many years ago, so that if we were ever a match for anyone, they could call on us. Hasn’t happened yet, but we would be honored if we ever had the opportunity.

And one day a family came from New York, because the mother needed a bone marrow transplant. (Denver had one of the top transplant units in the country, at the time.) The Rebbetzin assigned me to drive them around, and help them... and I learned more, and yearned more.

I had donated blood dozens of times (until I was no longer able to), and I wanted to donate a kidney if I were a match for someone in need. But then I was diagnosed with a connective tissue disorder, which means that all of my tissues are weak.

I am a private-duty nurse. I brought a friendly, chatty patient for treatment to a hospital here in Israel. As was her wont, she struck up a conversation with the doctor who joined us in the elevator, asking him what he did there. He is the head of the transplant unit.

Although, as a rule, I am not inclined to strike up conversations with strangers, I saw an opportunity. Before the elevator reached his floor, I blurted out, “Doctor, can a person with a connective tissue disorder donate a kidney?” He looked astonished, and exclaimed, “Of course not!” — to my great disappointment. I sadly relinquished my dream.

And then Mishpacha published the cover story about Rabbi Heber and his organization Matnat Chaim, in October 2018. I already knew about Rabbi Heber’s wonderful work, from Rabbi Grylak’s columns in April 2013 and October 2017. I rejoiced to hear that the absurd charges against Rabbi Heber had been dismissed, and I was fascinated to learn much more about Matnat Chaim, from a separate magazine included with that issue. And I began to daydream again. What should I say? Perhaps:

“Rabbi Heber, maybe my tissues are weak, but my kidneys work just fine! Even if they might not last as long as perfect ones, they could iy”H last for many years yet — and isn’t that better than nothing? If I’m a match for someone, and there is no other kidney that’s a match for them, my kidney could be”H keep them going for now. And if need be, chalilah, another donor might be found later....”

So I’ve been dreaming this renewed, revised dream for a year and a half, now. Maybe someday I will be privileged to donate a kidney and perhaps help to save someone else’s life. But it won’t be Rabbi Heber to whom I make my case, to my great sorrow. I do intend to make it, though, as I hope and pray that the wonderful work of Matnat Chaim will go on. May they ever draw inspiration from their founder a”h, and continue to inspire more and more people to give the gift of life.

—Devorah Gladstone, Ramat Beit Shemesh

Oops! We could not locate your form.