Pyramid Schemes

| January 3, 2023Ari and Ari retrace our forefathers' journey to Egypt

Text and photos by Ari Z. Zivotofsky and Ari Greenspan

If the tiny modern Jewish community in Egypt still links its mesorah to the time of the Chumash, how could we not feel like we were there, too? Standing in the central Cairo synagogue, allegedly built on the very spot where Moshe’s baby basket was pulled from the reeds, we imagined the sojourn of our People to the superpower of the time — the iron crucible that forged us into a nation

The Jewish connection to Egypt didn’t end with the sojourn of Yaakov and his sons to Mitzrayim and the Exodus 210 years later after the period of brutal slavery — a paradigm for all future enslavements. Jewish life in Egypt actually spans millennia, and amid all the ups and downs, great luminaries such as Rav Saadia Gaon, the Rambam, Radvaz, the Arizal and many more are associated with Egyptian Jewish communities.

Still, when visiting modern Egypt and exploring the Jewish connections, it is only natural to think back to our people’s earliest sojourn in that land, and remnants of the storied Egyptian dynasties can shed light on our nation’s formative years. As guest speakers on Miriam Schreiber’s Legacy Kosher Tours trip to Egypt, and in another private excursion to the Land of the Pharaohs, it wasn’t hard for us to put ourselves back in time. Indeed, driving from the airport to downtown Cairo, we went on a bridge that took us over the Nile, and just hearing that word conjures up images of Moshe in his reed basket. Later, as we were gliding down the Nile in a boat, we observed firsthand the dense reeds along the edge and were really able to envision a sweet Jewish baby being watched over by his concerned older sister from the banks of the Nile.

In fact, the Jewish community in Cairo still links its mesorah to the Jews in the time of the Chumash. One of our first stops was the famous Ben Ezra Synagogue, located in the old part of Cairo. This shul, where the Rambam is said to have davened, has been refurbished numerous times over the last 1,000 years and is today a major tourist site. While we stood there, groups of tourists from Europe, the US, and Asia filed in and heard from the Egyptian guide how the Nile allegedly used to reach the site where we were standing, and that site was, by tradition, the very spot where Baby Moshe’s basket had been hidden in the reeds.

Intrigued by the connection between an Egyptian shul where the Rambam davened and Moshe Rabbeinu, we set out to find what other traditions or links still exist in modern Egypt that bring us back to the stories that we read in the parshiyos this time of year.

Standing by the thousands-year-old pyramids and the Sphinx drive home not only the magnitude of the ancient empire, but the miracle of how Hashem brought Egypt to its knees

Wonders of the World

The massive pyramids, the sphinx, the Valley of the Kings, and the huge monuments that are part of the scenery of modern Egypt, drive home the magnitude of the empire that ancient Egypt was, as well as the ubiquitous avodah zarah in that land. After the Exodus, Hashem thrice banned Bnei Yisrael from returning. This prohibition is not a mere travel alert: The Rambam and other mitzvah tabulators include it in the 613 mitzvos. So how is it, then, that Jews have lived in Egypt for almost all of history?

We know from the Neviim that Jews were in Egypt from Bayis Rishon times. In fact, rabbinic authorities for the last thousand years have wrestled with that issue, but the fact remains that during all those years, large and prominent Jewish communities have lived in Egypt (including one great-grandmother of Ari Z.’s grandchildren). The heterim given are varied and range in their degree of permissiveness, but it seems that visiting does not pose a halachic problem, so off we went to explore more secrets of our ancient history.

Clearly, there are not going to be many physical remnants related to the Jewish people from that era, and most of those associations will require some degree of imagination. Wait — what about the pyramids? Weren’t they built by our ancestors? Well, actually not.

There were two basic building materials used in ancient Egypt: mud bricks and stone. The pyramids, which were intended to be long-lasting and have indeed weathered the ages, were made of stone. The Torah is quite clear that the Jews built with straw and mud bricks. Visiting the famous Giza pyramids, the enduring stones attest to the fact that according to the Torah’s description of the slave labor, the Jews did not build them. In fact, ancient Egyptian sources testify that stone construction was done by Egyptians who specialized in that, while brickmaking and building was done by foreign slaves.

The ancient mud brick buildings may not have survived, but some of the bricks have — and can still be seen with bits of straw protruding from them.

The Giza pyramids and the Sphinx are truly wonders of the ancient world, and we were awed by the engineering feat from all those thousands of years ago, sitting on what is today the outskirts of the modern sprawling city of Cairo. It was a colorful scene of tourists from all over the world with the aggressive vendors hawking merchandise and camel rides (“just for you, Brother,” or “no, a present, don’t need to buy”). While clearly not of the highest socioeconomic class, these vendors are impressively multilingual and can quickly identify the appropriate language for each tourist (“Shalom, rak dollar echad”), and would “generously” offer to take a picture with tourists and then demand payment for the privilege of having an authentic photo.

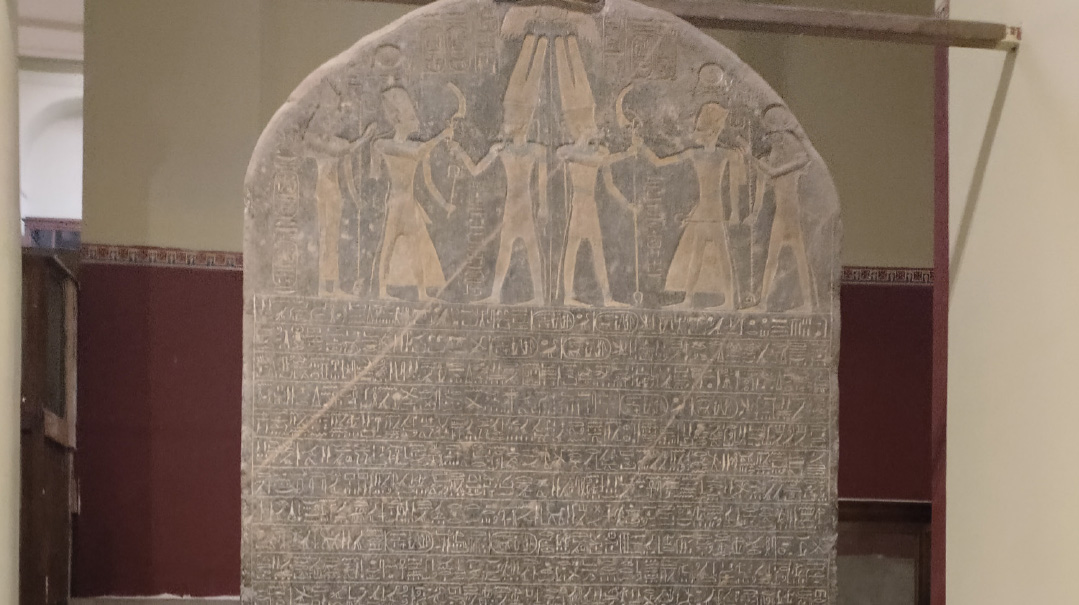

The hieroglyphics in this inscription by the pharaoh Meneptah, who is thought to have lived soon after the Exodus, is the earliest corroborative reference to the Jewish people

Mum’s the Word

Amazingly, there are some artifacts to be found in Egypt from around the period of Yetzias Mitzrayim (Jewish year 2448) that can help in understanding what our ancestors lived through. One fascinating place to visit is the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. While a lot of it still looks like it did when it opened over 100 years ago, the plan is for it to be replaced next year by the Grand Egyptian Museum currently under construction. But even the dated signage and decor couldn’t hide the treasures contained therein. For starters, we saw the Merneptah Stele, also known as the Israel Stele, an inscription by the pharaoh Merneptah, which is thought to be from shortly after the Exodus and contains a set of hieroglyphics that are translated as “Israel” and refers to them as a foreign, nomadic people. This is the earliest known extra-biblical reference to the Jewish nation.

Probably the most famous “occupant” of the museum is the mummy of King Tut and his belongings that were prepared for him to “take to the next world.”

Some researchers believe that King Tut, or Tutankhamun, was the son-in-law of the Pharaoh of Yetzias Mitzrayim. According to this theory, Pharaoh was Akhenaten, who hurriedly built a new city and temples for the revolutionary monotheistic religion he imposed on Egypt. And what did he build his city with? Mud bricks, which were the fastest way of building at the time. Upon Akhenaten’s death, these researchers believe, Tutankhamun seized power and returned Egypt to the old polytheist practices and ruthlessly persecuted the monotheists. Another theory considers Thutmose II as Pharaoh, the only mummy discovered whose body contains cysts, which may have been the result of the plagues of lice or of boils.

Mummies are prominently featured in the museum, and throughout archaeological sites in Egypt. Another famous mummy in the museum is that of U-ya or Yuya, a minister of Pharoah Amenophis III. Egyptologist Ahmed Osman has presented the claim that Yuya is actually Yosef and that right there in the Cairo Museum is the preserved body of Yosef Hatzaddik. We know from the Torah and from Sefer Yehoshua, though, that Yosef’s bones were taken out of Mitzrayim and into the Land of Israel (Osman’s theory is rejected by many biblical scholars).

Yet as we gazed at these preserved, ancient Egyptians, it made us wonder if Yaakov and Yosef had the same procedure done to them as all of these mummies who were once important Egyptian personalities. Regarding both Yaakov and Yosef, the Torah says “vayichantu,” a word not used in this regard anywhere else in Tanach and so its meaning is difficult to determine. Yet the process of mummification as described in the museum took 40 days, similar to what is described regarding Yaakov. Yet it is difficult to imagine that Yosef let his father undergo that process, one linked to Egyptian avodah zarah and that might be considered as disrespectful to the body.

Chasam Sofer says that Yaakov was indeed mummified, but without a need for the disrespectful evisceration. So, was Yaakov mummified like all of those pharaohs on display, or merely embalmed? Since we believe Yosef is buried in Shechem and not in the Valley of Kings, we don’t think that Yuya was Yosef and we don’t know how their bodies were processed, but it is clear that Yaakov, Yosef, and the other Jews of the period saw many mummies and were familiar with the process.

The mummies — many of them Egyptian pharaohs and noblemen — are all kept under tight security to prevent antiquity theft, but likely not to guard against what it seems Egyptian Jews were involved in for centuries: the business of buying and selling pieces of mummies for medicinal use. The leading 16th century Egyptian posek, the Radvaz, permitted consuming mummies for medicinal use and doing business with them. The early 18th century Mishneh LaMelech concurred, but barred Kohanim from selling them.

A Better Afterlife

The Abu Simbel temples in southern Egypt are another site where we can get a taste of the Exodus. Among the grandest monuments in Egypt, these temples were built for the Pharaoh Ramesses II, who is often identified as the Pharaoh of the Exodus (he was the builder of the city of Pi-Ramesses, possibly “Pitom and Ramses,” which were built by the Israelites). These massive rock-cut temples with enormous statues of the pharaoh and his family members guarding the entrance, were at the southern boundary of the Egyptian empire. Seeing them truly gives one a sense of the grandeur and power of the empire and its ruler that HaKadosh Baruch Hu brought to their knees.

Indeed, these temples were built by the Egyptians in order to impress upon their southern neighbors, the Nubians, their technological and military prowess. The interior of these monuments are covered with bas-reliefs including some that depict battle scenes with the king on his chariot shooting arrows and leading his troops. Other images of interest include a “divine cow,” reminiscent of the Eigel Hazahav which was created shortly after leaving this culture, and massive snakes, reminding us of the miracle performed by Aharon HaKohein with his staff.

In the Deir el-Bahari complex of tombs opposite the city of Luxor, is a fascinating drawing of an Egyptian god at a potter’s wheel fashioning man, an expression of the Egyptian belief that the first humans were fashioned from the silt of the Nile, similar to how pottery is produced. And in many temples and tombs, various drawings depict preparations for the afterlife and the perception of the afterlife itself. In one royal tomb after another, we saw the walls covered with texts from the Book of the Dead and began to understand this huge focus on death and the afterlife.

But it’s not only on the afterlife. The drawings and hieroglyphics on papyri, stone tablets, and sarcophagi — in the museum and on the walls and ceilings of ancient pyramids and sites throughout Egypt — depict daily life focusing on the powerful god-like rulers along with the Egyptian gods and their relationship with the human monarch. Egyptian males are usually drawn clean-shaven, although the pharaoh generally has a beard, as a sign of his divine nature. So it was surprising to see drawings of groups of men with beards, who are assumed to be foreigners, possibly even Israelites, reminding us of how when Yosef is brought before Pharaoh, he was first shaved.

While there were many mythological references we didn’t understand, some of those depictions helped us understand the cultural context of the Jews in Mitzrayim, Chazal’s explanations of how difficult it was to extricate the Jewish People from that environment of avodah zarah, and of course, how Hashem’s putting Pharaoh in his place was an unthinkable blow to Pharaoh’s status and essentially to their gods as well.

Like good tourists, we visited a Nubian tourist village set to display their culture and traditions. In several of the houses, there were large pits holding what they claim is a typical pet, a crocodile. While it’s not exactly a cute pooch, the importance of the Nile crocodile to Nubian and Egyptian culture is as ancient as the pharaohs. Some commentaries suggest that the second plague, Tzefardei’a, is not a frog, but a creature that emerges from the Nile and snatches people, quoting an Arabic word for crocodile.

Rabbeinu Chananel (Shemos 11:2) points out that when Moshe Rabbeinu promised Pharaoh that the Tzefardei’a would be removed from their homes but would stay in the Nile, the fact that the lethal crocodile is in the Nile to this day is a reminder of the Makkos. The ancient Ipuwer Papyrus, which some researchers consider a confirmation of the biblical account of the Exodus because of its statement that “the river is blood,” also mentions crocodiles.

No Praying

Tourism plays an important role in the Egyptian economy, and thus the government works hard to ensure the safety of their tourists — especially in light of several terrorist attacks that targeted tourists over the years, such as the triple Sharm el Sheik bombings in 2005, the Dahab resort bombing in 2006, the downing of a chartered flight in 2015, and the stabbing at resort hotel beaches in Hurghada on the Red Sea in 2017.

Individual tourists don’t usually have a security detail, but as we were a group of Jews from Israel, we had a personal police escort. Even when we went for a stroll in the souk in Alexandria at two a.m., they were at our side. They were very friendly and even let us ride in their police car for photo ops. As part of a group, we also had an armed guard on our bus at all times, as well as a police car escort, and all stops on the itinerary had to be cleared with the “tourist police,” limiting our flexibility for schedule changes. We actually thought it a bit overly conspicuous having a police car in front and behind us at all times — talk about a way to attract attention to a group of tourists.

Tourist buses had to be on the intercity highways before a certain hour in the afternoon due to security concerns, which meant we once had to take some back roads instead of the main highway. With a group of middle-aged tourists, that made a group bathroom stop a little challenging, since there were no rest areas on the non-highway (the ones on the highway weren’t exactly what we were familiar with in our more western countries, but they were relatively clean, with a clerk collecting a few Egyptian pounds at the entrance). Our guide had the bus pull over at a tiny kiosk along the dusty road, and asked the owner if there was a bathroom we could use. He graciously let our entire group enter the courtyard behind his kiosk and use his family’s private bathroom, offering us a glimpse into the life of this typical family: a small but neat house with a few rooms, dirt floors, rudimentary furniture and basic electronics, and a bathroom with a rudimentary sort of indoor plumbing (including filling the tank from a bucket for every flush). We rewarded them generously for their kindness in addition to buying kosher snacks at the kiosk (unbelievable, but all over Egypt there were kosher snacks and drinks for purchase at the various rest stops), and this providential pit stop probably increased their yearly salary significantly.

A Tourist Police booth. We felt protected by them, until they fined us for davening Minchah in public

We did get into one squabble when we made a Minchah stop at a particular site of some ancient statues. Although we stood between the buses and tried to be discreet, either because this public display of religion was disturbing to the locals, as it’s against the law to pray in public, or because the aggressive hawkers were upset that we rebuffed their offers of buying their souvenirs, a fight ensued, reaching the point where our brave guard nearly came to blows with the locals. We were grateful that that scenario ended quickly, and we hope that he and our guides didn’t suffer any additional repercussions after receiving an official ticket and reprimand from the Tourist Police.

We didn’t learn how to make papyrus boats, but Ari G. got a lesson in how to turn the reed into ancient Egyptian paper

Paper Trail

The reeds growing in the Nile are not mere riverbank greenery, but are often the papyrus plant. Papyrus was used for a variety of purposes by the ancient Egyptians, most notably as the source of papyrus paper, one of the earliest types of paper. In the dry climate in Egypt, papyrus — formed from highly rot-resistant cellulose — is extremely durable, and thus there have been extraordinary finds of ancient documents, including the Elephantine Papyri, describing a community of Jews in Egypt during the late Bayis Rishon period. The ability to see the remnant of this community in real time, one of the earliest diaspora communities and one that provides some of the earliest extra-biblical mention of mitzvos, is fascinating.

Travel straight down the Nile about 800 km from Cairo, and you’ll reach the small island of Elephantine. It was home to a community of Jewish mercenaries from before the destruction of the first Beis Hamikdash until the end of the Persian rule. These Jews lived there with their families and were charged with guarding the southern border of Egypt. The hundreds of documents that make up the Elephantine Papyri are mostly in Aramaic and span about 100 years of Jewish legal documents as well as correspondences with the Jewish community of Eretz Yisrael from the 5th and 4th centuries BCE. One of the most famous is the “Passover Letter” of 419 BCE, which gives detailed instructions regarding keeping Pesach.

This community, living in a time when korbanos were still being offered in Yerushalayim, actually built their own mikdash and for a short time brought korbanos, reminiscent of a similar phenomenon described in the Gemara about 250 years later in northern Egypt. We were able to see the remnant of their city, and even of their mizbeiach.

We know that papyrus isn’t only for paper. Owing to the highly buoyant stems, papyrus was often made into boats or rafts. When baby Moshe could no longer be hidden, his mother put him into a boat of gomeh. This is variously translated as bulrush or the closely related papyrus. These were enough reasons to visit a papyrus factory, albeit the tourist version, where we received training in how to soak, peel, and beat the reeds in order to produce the paper. Alas, boat-making was not included.

The small island of Elephantine had a kehillah of Jews who were charged with guarding Egypts’ southern border. Living during the time of the Beis Hamikdash but so far away, they built their own mizbeiach for bringing korbanos

Overflow Blessings

We traversed Egypt by bus, train, plane, and boat, and in whatever mode of transportation, the Torah’s description of Egypt was displayed in front of us: The Egyptian economy and agriculture is still centered around and wholly dependent on the mighty Nile River. The Torah (Devarim 11:10) describes Egypt as a land that is “irrigated by foot,” that is, one kicks dams open and closed so that the Nile water can flow to the fields (or that one must carry buckets of water by foot from the river to the fields). Nearing the Nile or Nile Delta, the area is lush green, but as soon as you leave the river banks, you’re in a desert. Until today, the vast majority of the population still lives within a short distance of the Nile and their lives are still very much intertwined with the lifegiving waters of the Nile. Villagers still do their laundry in the Nile, travel along it in old, small boats, and transport goods along its banks in donkey-drawn wagons — all of it looking like not that much has changed from days of yore.

The transition from the fertile region in proximity to the Nile to the inhospitable desert just a short distance away is sharp and frightening. It drives home the Torah’s description that, unlike the Land of Israel, Egypt does not survive on rain but requires the waters of the Nile. This is explained by Rashi and Ramban as both a benefit and a liability. Although one must work to transport the water, the water itself is guaranteed, so there is no need to turn heavenward. In Eretz Yisrael there is no Nile and no guarantees, but when we Jews turn Heavenward and develop a relationship with Hashem, we can look to Shamayim for the rain that will be sufficient for all of our needs — no transport necessary. May we indeed be worthy!

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 943)

Oops! We could not locate your form.