Put Your Foot Down

“I was also crying and screaming, but in order that these Jewish cries were not in vain, I attached them to a song for the Creator”

MY father a”h would always tell us about Yom Kippur of 1941, right after he was drafted to the US military. He was scheduled to have his physical in Texas on the day after Yom Kippur, so he traveled by bus from New York to Texas, and stopped off in Kansas for Yom Kippur. He realized he only had leather shoes on him, so he quickly went to a Thom McAn shoe store and found man-made shoes for three cents. The shoes were a little tight, which made them significantly less comfortable, since my father’s custom was to stand in shul an entire Yom Kippur.

Right after the fast, my father continued on to Texas for his army physical. When he got there, the doctor looked at his legs and feet which were swollen and full of sores, though it was actually just a bad case of blisters from standing in shul for so many hours. While the doctor was trying to figure out what kind of disease it was, my father was actually having a hard time keeping a straight face. Finally, the doctor said he’d never seen such a thing before, sent my father home so that he could get his legs checked out, and dismissed him from active duty. My father smiled the entire trip back, knowing that his dedication to Yom Kippur saved him from going overseas.

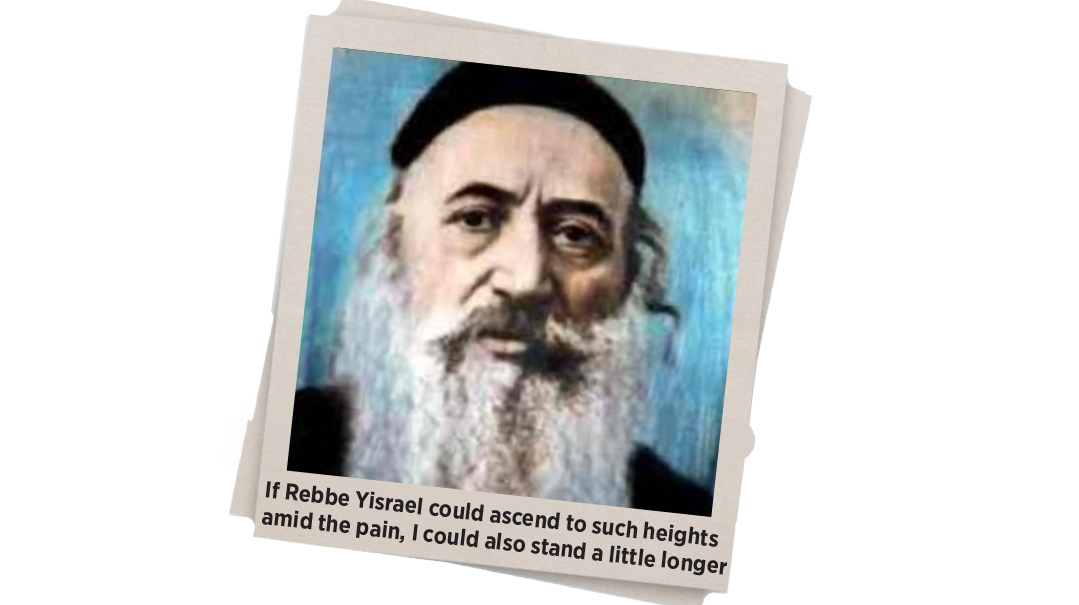

And so, when Yom Kippur comes around and I have an urge to sit down and give my aching feet a break, I always think of my father’s endurance, along with the well-known story of the first Modzitzer Rebbe, Rav Yisrael Taub ztz”l, and his esoteric composition of the Ezkerah piyut we say at Neilah on Yom Kippur. It puts my own temporary discomfort in a whole new light.

The Rebbe, who was the first in a line of Modzitzer rebbes to leave the stamp of music on the chassidus, was diabetic, and the doctors felt that he should go to the healing baths in the Czechoslovakian resort town of Karlsbad to help the circulation in his feet. In 1910, while in Karlsbad, the Rebbe went for a stroll and, overwhelmed by the beauty of the resort, thought of Yerushalayim that lay in ruins. He immediately thought of the stanza from Selichos and Neilah comparing the ruins of the Holy City to the beauty of modern cities:

“Ezkerah Elokim v’ehemaya… I remember and I painfully groan, as I see every city, built to beautiful great heights, while the city of Hashem has reached the lowest levels of She’ol. But despite all this, we belong to Hashem and our eyes look to Hashem.”

And right there, he composed a haunting melody to the words, later telling his chassidim that he had brought them a souvenir from Karlsbad — the tune for “Ezkerah.”

But the Rebbe was never satisfied with the niggun; he felt he hadn’t done the holy text justice, and during the next two summers in Karlsbad, he tried to expand the niggun, but it just wouldn’t go. The Modzitzer chassidim call this melody “Ezkera HaKatan” (the short Ezkera) because three years later, under extremely painful circumstances, the Rebbe would compose a longer and more complex version.

Meanwhile, the condition of his legs got so bad that he developed gangrene on one foot and went to a top professor in Berlin for a medical consultation. The professor concluded that to save the Rebbe’s life, an immediate amputation was necessary. Some claim that due to the Rebbe’s weak heart, anesthetizing him would have been dangerous, but in fact, I heard from his great-grandson, Rabbi Shaul Shenker, that the Rebbe himself didn’t want to be put under even though the pain would be excruciating, because he didn’t want to lose his conscious connection to Hashem for even a moment.

The Rebbe, racked with unfathomable pain, elevated himself by singing several musical pieces that took him into a higher realm. Later, on the medical rounds, the doctor asked the Rebbe, “How did you withstand the pain without crying out?!” The Rebbe answered, “I was also crying and screaming, but in order that these Jewish cries were not in vain, I attached them to a song for the Creator.”

While he was in Berlin recuperating, the Rebbe looked out the window, saw the huge metropolis before him — and knew the time had come to complete the Ezkerah niggun.

The Rebbe himself told the story at the seudas hoda’ah when he came back to Warsaw in the winter of 1914 and sang the new, longer melody for his chassidim.

But you won’t find the “Long Ezkerah” (comprised of 36 sections and sung over half an hour) recorded anywhere. The Rebbe “locked” it, and it’s only sung by select chassidim on his yahrtzeit — and not even on Yom Kippur.

May the niggun soon be unlocked and the piyut no longer relevant, when Hashem’s City will be rebuilt in all its glory.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 930)

Oops! We could not locate your form.