Part of Something Bigger: Be’er HaTorah, Gateshead

The boys would go home for Pesach and Succos, and the place lost its energy; the town became a shadow of itself

“I think I’ll go shopping now,” I said to my mother.

I grabbed my handbag, made sure I had money, then checked the time.

“No, actually, I won’t go now. It’s boys’ time.”

That’s what it was like to grow up alongside the yeshivah. As a resident of Gateshead, I wasn’t bound by the boys’ or girls’ times for shopping (they were for the many students who filled the town), but I didn’t want to be the lone girl in a swarm of boys at the grocery.

Gateshead is a small place, and we grew up around the five yeshivos that call it home: the two main yeshivos and three smaller yeshivos. The great yeshivah ketanah was two blocks from my house. If I was going anywhere, I walked past the yeshivah.

Our school didn’t offer school lunches, and so we’d go home in the afternoon and then come back. That short walk coincided with the end of seder in the yeshivah. Many a time I’d see Reb Chaim Kaufman ztz’’l flanked by the bochurim. I remember the way they surrounded him, the kavod they had, the intensity on their faces. I was a young girl, but these things make an impact.

In a quiet town like Gateshead, if there was any noise, it was coming from the yeshivos. You could feel the energy, the chiyus, from the buildings, from the dormitories. I’d be walking home at night and suddenly there’d be a burst of activity, a crowd of bochurim doing Kiddush Levanah and then breaking out into a dance.

At the end of the zeman there was a day called “chavrusa politics,” when each person worked out whom he would learn with the following zeman. The streets were full of the boys, everyone talking to everyone else, trying to sort out three chavrusas for themselves. The noise, the vigor — you couldn’t walk past the yeshivah on those days.

And then, like a curtain drawn, silence. The boys would go home for Pesach and Succos, and the place lost its energy; the town became a shadow of itself.

Until they’d all come back…

My father is a maggid shiur at Be’er Hatorah, one of the smaller yeshivos. I remember the boys rallying around my father, walking him home at the end of the day.

Every second Friday night they had a vaad at our house. They’d say divrei Torah, then sing for hours into the night. I remember the nosh we used to lay out for them. And the songs. As a child I fell asleep to those songs.

I realize now what those Friday nights were to them, a slice of warmth and connection. This was their outlet, their bit of family. When I hear those songs today, I feel that spark, those beautiful voices rising, perhaps plaintive or homesick, finding connection to each other, to Shabbos. Hearing those songs takes me to a different place.

I remember siyumim at our house, and once a zeman the entire shiur used to have a Shabbos seudah in our home.

For the Yamim Noraim, the privileged family members of the faculty used to daven with the yeshivah. The tefillos were in another realm, vocals rising a hundred-strong. The tunes play in my head still; I hear those young, earnest voices. No grand shul is able to recreate what we had there in that simple dining room of the yeshivah.

The boys would then eat their Rosh Hashanah meal in the dining room where we’d been davening. During the davening, the non-Jewish kitchen help would load the side tables with plates, cups, and cutlery. At the end of davening, we’d quickly set up the tables and lay out the place settings. I remember redoing the napkins in the cups, the kitchen help had done it distractedly and quickly, but I wanted the boys who’d davened all day to have a beautiful setting for the Yom Tov meal.

Purim in Gateshead started a week before with parshas Zachor. We’d walk around the town to see what shtick the boys had made. It could be a makeshift Haman, a banner strung across the street, or a wild balloon arrangement.

For us, Purim itself was about the yeshivah bochurim in the house. We have a picture of a gadol in the dining room, and one boy took hold of the picture and wouldn’t let go.

Other boys held on to their Gemaras and, tears streaming, begged Hashem to open their heads, to let their learning seep in. This is what emerged when they were inebriated, what I saw year after year.

When I got married, the whole yeshivah joined in to dance with my father. It was leibedig, it was fire, they stamped the night away.

The yeshivah hosted a sheva brachos for us in that dining room where we’d davened Yamim Noraim. The boys became part of the simchah. The boys catered, they served, and those less domestic took part in other ways — they printed bentshers with our monogram on them and proudly gave them out when it was time to bentsh.

The memories of my childhood are linked to the yeshivah; it made me feel I was part of something bigger.

I don’t live in Gateshead anymore, and I wish my kids would have some of what I grew up with. I walk the streets with them looking for parshas Zachor shtick, but there’s none to be found. Sometimes on a Friday night, I’ll sing one of those timeless songs, and I hope that in my voice, in the yearning, my children can hear something of the past.

At a Glance

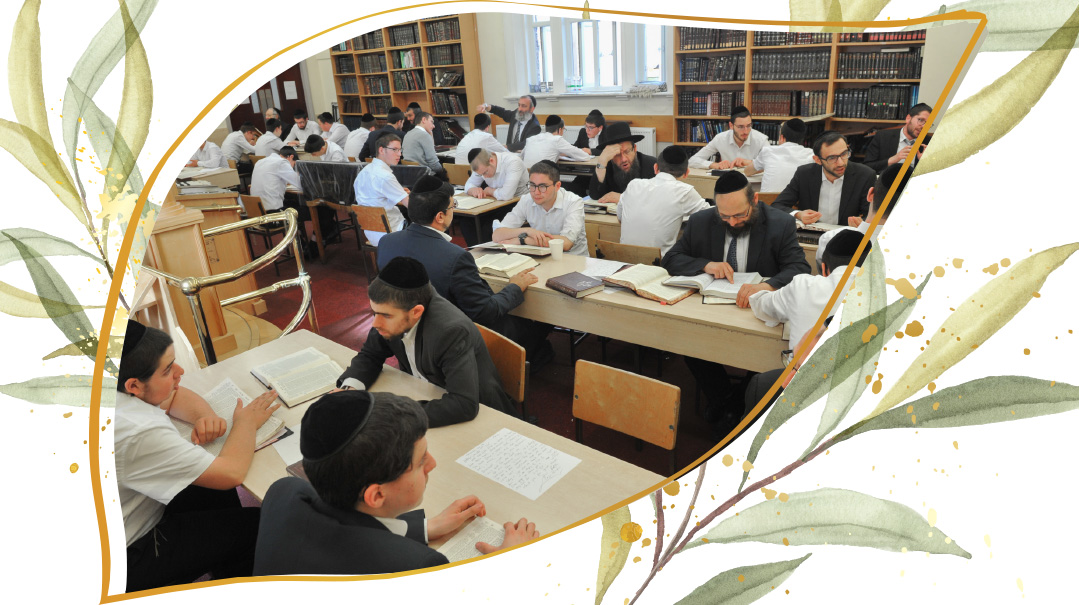

Yeshivas Be’er Hatorah was founded in 1998 by Reb Yechiel Cohen and Reb Yissochor Lichtig. This close-knit yeshivah helps bochurim leaving school meet the demands of the mainstream yeshivah system.

Be’er Hatorah has also successfully incorporated the V’haarev Na chazarah program, ensuring every bochur is given the chance to taste the sweetness of Torah. The hundreds of alumni, who are outstanding bnei Torah, are testimony to the mission of the yeshivah.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 795)

Oops! We could not locate your form.