Numbers Game

Elite polling guru Dave Wasserman on Democrats' redistricting plan

Republicans who think the US House of Representatives is already in the bag for them pending this November’s midterm elections had better sit up and take notice of Democratic redistricting efforts. And the fault lines will run right through a handful of states including New York.

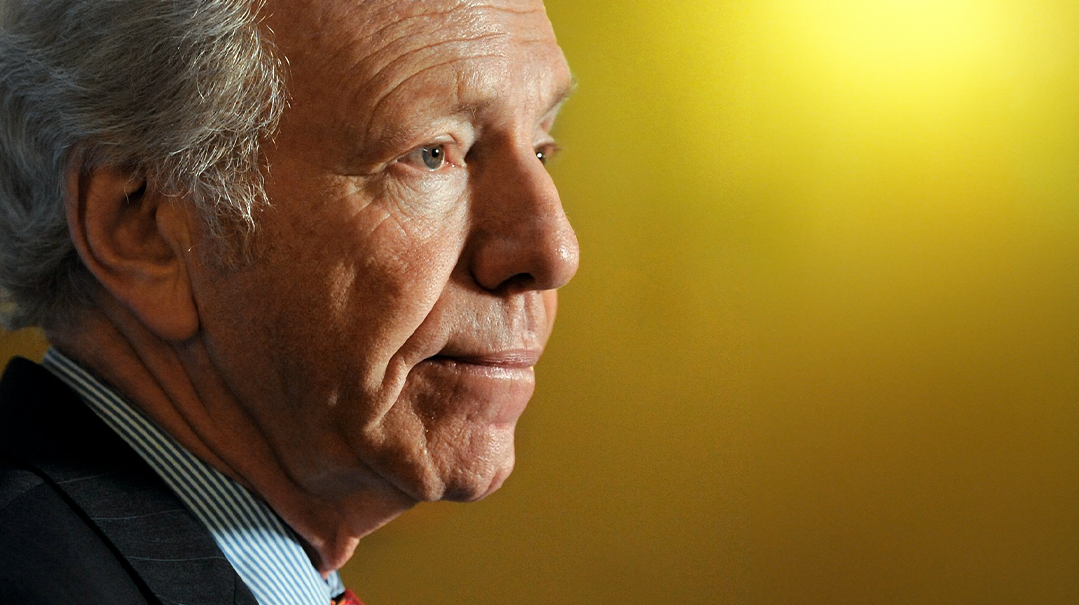

So says polling guru Dave Wasserman, whose catchphrase, “I’ve seen enough,” has become a political sphere meme.

Dave Wasserman, 37, crunches survey numbers the way most Americans eat breakfast cereal. The prominent Cook Political Report’s elections expert, whose purview is the House of Representatives, is on the elite list of prognosticators whose calling of races is deemed definitive. That list includes the Associated Press, CNN, Fox News, Reuters, and the New York Times. Nate Silver of the FiveThirtyEight blog marveled at how “Wasserman’s knowledge of the nooks and crannies of political geography can make him seem like a local.”

Wasserman’s blog entry for FiveThirtyEight, written two months before the 2016 election and titled “How Trump Could Win the White House While Losing the Popular Vote,” proved prescient, and cemented his reputation as an elections wunderkind.

For the upcoming midterm elections, Wasserman’s crystal ball predicts that Republicans are on track to take back Congress, “perhaps by a convincing margin.” He estimates that they could win between 15 and 30 House seats, and one to three Senate seats.

That, however, is predicated on a fed-up electorate intent on “throwing the bums out,” as the axiom goes. If this were a normal year, predicts Wasserman, then Democratic efforts to maneuver the post-redistricting maps would give them a shot at keeping their majority.

Wasserman — whose Twitter handle is @Redistrict — has seen enough to confirm that the Democrats’ redrawing of Congressional district boundaries has gone from insider baseball to a national story.

The new maps, which are constitutionally required to reflect the outcome of the 2020 census, are right now in the process of being finalized by state legislatures across the county — and many of them are being tilted in favor of the Democrats. This could decimate Republican caucuses in blue states such as New York.

Ominously for Republicans, Wasserman has suggested that barring a “red wave” of GOP victories throughout the country, Democrats are on their way to retaining their majority in the House, simply by redistricting their way through.

Fiddling with the Data

Dave Wasserman has always loved numbers. Born in New Brunswick, New Jersey, in 1985, Wasserman, as his name may indicate, is Jewish, and came from a family that reveres data — his father, Bruce, taught biochemistry and food science at Rutgers University.

As an 11-year-old, Dave says, he became “obsessed with politics.” He was flipping through the TV channels when he came across C-Span, the channel that broadcasts House and all political proceedings, and became intrigued by the congressional floor debates.

“I started writing down a list of all the names, states, and parties of all the members I’d see speaking, and my goal was to collect all 435 of them,” he says. “So that’s how I got into it. I started reading the Almanac of American Politics and watching more shows and reading more books about who these members were.”

He did it as a hobby, not knowing he could turn it into a living — until he got to college and studied under Professor Larry Sabato, a political prognosticator at the University of Virginia, whose Crystal Ball is legendary in the industry. That led to an internship with the Cook Political Report in 2005, and a full-time job two years later, at the age of 22.

Elections, he discovered, never end — they just fade from consciousness.

“The election cycle is never really entirely out of view — by the time one election is over, we’re already talking about the next one,” he says with a chuckle. “In between, we spend time profiling the new members who have been elected, or sizing up the lists of candidates who can run the next time. So increasingly, there’s no such thing as an off year.”

Wasserman lives in Alexandria, Virginia, with his wife Katie, whom he met while both were on a college trip to Israel. They married in 2015.

When he’s not fiddling with the data points, he’s fiddling with his fiddle.

“I’ve been known to play Hava Nagila at bar and bat mitzvahs, so I have that going for me,” he reveals. “I also play a little bit of klezmer. And I dance a pretty good hora, if I can say so myself, but I’ll let others be the judge of that.”

He even played at his own wedding.

Bold Prediction

Wasserman’s big break came in 2016, when he correctly predicted Trump’s narrow path to victory. His prediction went against the zeitgeist of his fellow prognosticators. Nate Silver, the 2012 election polling breakout star who nailed Barack Obama’s victory margin in 49 of the 50 states, had given Trump a mere 15 percent chance of winning. And that was the kindest of all forecasts — the Huffington Post gave Hillary Clinton a 98 percent chance of taking the White House, and that was the general feeling of political pundits.

“I remember in June 2020, I pointed out that it was curious that the Clinton campaign had not made ad reservations in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin,” he recalls, “and I wrote about that for FiveThirtyEight. I always believed that if Donald Trump had a path to the White House, it ran through those states.”

Wasserman was challenged by the Clinton campaign, who sent him an email claiming that their dearth of ads was a show of fiscal discipline, since those states hadn’t gone Republican since 1988.

Ultimately, since data doesn’t care about feelings, Trump targeted those states as must-wins, and he picked up each one of them, giving him the White House. But not the popular vote. Exactly as Wasserman predicted.

That election, Wasserman says, proved to be among the greatest surprises of his career — along with House Majority Leader Eric Cantor’s 2014 primary loss to a Tea Party candidate, and Rep. Joe Crowley’s loss to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in 2018.

But he was not the only one to be astounded by Trump’s victory.

“Everyone, except he and his team, were somewhat surprised by what transpired on election night,” Wasserman notes. “But you know, he did exactly what he needed to do. There was no other way he was going to win the race other than very narrowly, and probably losing the popular vote. And that’s exactly what happened.”

Although that was the biggest shocker of his 15 years in electoral predictions, it was not the polling industry’s worst moment. That was the 2020 election, which Trump lost, but by a much tighter margin than the double-digits forecast.

“Clearly,” Wasserman says, “the polling error in 2020 was even larger than the one in 2016.”

Although out of the 159 million votes cast, Joe Biden received millions more, under the Electoral College system, he needed to win Arizona, Wisconsin, and Georgia — which he did, by a grand total of just 42,915 votes.

Mapping the Way to Victory

Fast-forward to 2022, and with Republicans confident of wresting the House from Biden’s party and turning the president into a lame duck, Wasserman has one message: Not so fast.

The reason is another of the data guru’s core competences, redistricting.

If 80 percent of success is showing up, then elected officials want to control who shows up at the voting booth. That’s the point of congressional redistricting, the once-a-decade process that has consumed Dave Wasserman’s time these past few months. With the decennial census jumbling hundreds of districts across the country, both political parties are scrambling to get ahead of the game. The states controlled by a single party have approved maps that heavily favor that party’s side.

The conventional wisdom is that the Democrats’ bare majorities in the House and Senate — a five-seat advantage in the House, and a 50-50 Senate secured only by Vice President Kamala Harris’s tiebreaking vote — will not survive President Joe Biden’s plummeting approval ratings.

But Democratic state legislators are hoping to defeat that conventional wisdom by carving out districts favorable to reelecting their members, while handing Republicans districts that went for Biden in 2020. Of course, in the states they control, Republican legislators are doing the same thing, to their own party’s favor.

Overall, Wasserman says that Democratic remapping efforts have netted them an additional advantage of six seats. However, that does not include the ten or so states that have not yet submitted their maps, nor does it take into account court challenges. Courts have already thrown out redistricting maps in North Carolina and Ohio.

“As geographic polarization has become sharper,” Wasserman says, “redistricting has become existential to political outcomes. It used to be that someone with an R next to his name could win a seat in Congress on the Upper East Side. I mean, that was really only 30 years ago.

“Today, most of New York consists of precincts that are either more than 80 percent Democratic or more than 80 percent Republican. So it’s extremely difficult to achieve any politically proportional outcome, unless you were to consciously connect various Republican-voting ethnic groups in South Brooklyn, in parts of Queens, and so forth.”

Overall, New York state is very solidly Democratic, but not unanimously so — Donald Trump won 35 percent in the 2020 election. Yet the new district maps would award 22 of the state’s 26 House seats to Democrats and just four to Republicans, half what they have now. This means that despite the GOP having won a third of the vote in 2020, they would receive just 15 percent in congressional districts.

The way the Democrats achieve this is by hacking up the districts that strongly favor the GOP. For example, the 11th district, which covers solidly Republican Staten Island and parts of Brooklyn, enabled the GOP’s Nicole Malliotakis to defeat Democratic incumbent Max Rose by 53 percent to 46 percent in 2020. The new maps, though, add to this district the uber-liberal neighborhoods of Sunset Park, Red Hook, Gowanus, Windsor Terrace, and Park Slope — where co-op shopping is the norm, Bill de Blasio had his political birth, and such progressive concepts as cloth shopping bags had their incubation.

Alternatively, the new maps effectively eliminate Republicans such as Rep. Lee Zeldin, part of whose Long Island district was lopped off and added to that of fellow Republican Rep. Andrew Garbarino, who won a tight race two years ago and now faces a run for his money. Zeldin is passing up reelection to Congress to run for governor instead.

The maps were signed into law by Governor Kathy Hochul, but a lawsuit has been filed against them. A court will hear the challenge on March 3.

Smothering the Jewish Vote

Orthodox Jewish voters, too, have been caught up in the remapping drama, particularly in the 10th District represented by Rep. Jerry Nadler, the dean of the state’s Democratic House conference.

The maps make no significant revisions to Nadler’s district, which starts up in Manhattan’s progressive West Side, meanders its sloppy way down to the heart of conservative Boro Park like a lost drunken sailor, then makes a few figure-eights before burying itself somewhere in Gravesend on Brooklyn’s southern tip.

It is obvious that this was done to diminish the power of the Orthodox voting bloc — which make up “my guess is about five percent of the state,” one knowledgeable person told me — with one major concentration in Boro Park.

“There’s no doubt that over the years, the 10th Congressional District has been designed to dilute the influence of Orthodox Jews in Brooklyn,” Wasserman asserts. “Not only does the Manhattan section of the district outnumber the Brooklyn section, but over time, as the Orthodox vote in Boro Park and elsewhere has grown almost universally Republican and pro-Trump, it’s increasingly in Democrats’ interests to dilute their votes with some of the most liberal portions of the city. So it’s no surprise that Democrats drew the shape they did.”

Indeed, in the past few elections, Nadler has lost the Brooklyn portion of his district by upwards of 80 percent, but still won by comfortable majorities overall. According to a Jewish Community Relations Council study in 2011, Nadler’s district is home to 61,800 Orthodox voters, which amounts to less than 10 percent of the total district voter population of 730,000. Padding Nadler’s liberal district with Boro Park negates the neighborhood’s voting power, freeing him from having to take the community’s political suasions into consideration.

Another reason this district was drawn this way is the raw political fact that nobody else wants Boro Park, Wasserman says. It would make more geographic sense to add the neighborhood to Congresswoman Nydia Velázquez’s nearby 7th District, which covers North Brooklyn and parts of Williamsburg. But political sense outweighed geographic sense, says Wasserman.

“One of the reasons why [Nadler’s] district looks so bad on this map is due to the considerations of the surrounding districts,” he notes. “Nydia Velázquez did not want to give up her home in Red Hook, and Democrats wanted the Staten Island district to include [liberal voter-rich] Park Slope. So there’s really no way to achieve all of those things without very ugly lines.”

Taken together with state senate districts, state assembly districts, and City Council seats, nearly every Orthodox jurisdiction in New York has been sliced and diced among three, four and even five different lawmakers. This has happened every census for decades, but askanim had hoped that this time would be different, for several reasons.

First of all, the electoral components of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which mandated that Brooklyn have three districts where blacks constitute a majority, were struck down in 2013. This opened up parts of Flatbush to be joined together into a second “super Jewish” state senate district, similar to the once created ten years ago in Boro Park (Simcha Felder holds the seat). That hasn’t happened.

Second of all, Rockland County has several Orthodox communities, such as Monsey, Spring Valley, New Square, Airmont, and Kaser, which are now divided among four state assembly seats. Efforts to consolidate them have failed — although Rockland County legislator Aron Wieder, a chassidic Jew, said he is still mulling a campaign for one of the districts that was bulked up with more Orthodox voters.

The Balkanized City

Jews are not the only ones disappointed with the maps. The most novel part of the redistricting effort was the creation of a new House seat in Brooklyn’s Sunset Park, a heavily Asian neighborhood bordering Boro Park. This has angered blacks and Hispanics, who accused mapmakers of seeking to dilute the influence of both their communities.

Wasserman says that such a reaction is inevitable in a climate in which parties nationwide are jostling to achieve through redistricting what they can’t through elections.

“New York City is a politically balkanized place,” Wasserman says, “and it’s impossible to achieve equal representation for each group through redistricting, especially at the congressional level, where districts are so large. There’s no question that the map that existed for the last decade, and the map that Democrats just passed, have advantaged Democrats by pairing some of the most conservative parts of the city, which are obviously Orthodox, with some of the most liberal parts. So some groups are favored over others. And partisanship is the main driver.”

This final point was disputed by Assemblyman Ken Zebrowski, the Democrat leading the mapping effort, during a floor debate last month. He argued that the team looked strictly at census data for determining district lines, not voter enrollment.

“If New York’s Democrats didn’t take partisanship into account,” Wasserman counters, “then I built the Brooklyn Bridge.”

Zebrowski himself, in fact, gained significantly from the gerrymander. An anti-Orthodox politician from Rockland County, his maps mysteriously excluded from his own district part of heavily frum Monsey, as well as Airmont and Wellesley Hills.

The ripple effects from the new maps have been immediate.

Rep. Kathleen Rice from Long Island became the 30th Democrat nationwide to announce she will not seek reelection. The new map did not considerably alter her district, but last year’s Republican sweep meant that it no longer was a reliable Democratic district.

In Boro Park, Kaegan Mays-Williams, a socialist, dropped her campaign against state senator Simcha Felder after the new lines placed her in the nearby district of state senator Kevin Parker, whom she will challenge instead.

A curious outgrowth of the redistricting effort has already taken place in Westchester County. Rep. Jamaal Bowman, a Democratic freshman and a socialist, announced last week that he was removing his name from a letter supporting the Abraham Accords. He has danced at the edge of the envelope since first entering Congress in 2021, not joining the anti-Israel Squad, and visiting Israel as part of a J Street mission. But with his new district lines relieved of heavily Jewish Riverdale, he can devote his energies to improving his fraying relations with the progressive flank.

Bowman, who defeated the strongly pro-Israel Elliot Engel, now says the peace agreements Israel signed with five Arab nations “will only escalate violence in the Middle East” since it “unhelpfully isolates Palestine.”

The Nonpartisan Puppet Commission

Redistricting was not supposed to happen like this. Voters approved a referendum in 2013 to hand the map-drawing procedure to an independent commission, after the post–2010 Census process descended into mayhem that ended up in court and nearly interfered with the 2012 election. The commission was divided into equal parts Democrats and Republicans.

The panel did their job, with the Democratic half proposing a map that moderately favored their party, and Republicans putting forth a plan that helped them. But since the commission had no mechanism to deal with tie votes, negotiations between the two halves broke down, with each side blaming the other.

As expected, the legislature’s Democratic majority rejected both plans and then proceeded to write their own map, which dug much deeper into Republican districts than the commission’s Democrats had done.

Nobody, least of all Wasserman, is surprised that the will of the voters in naming a nonpartisan commission was overturned. But he notes that a state court in Ohio struck down redistricting maps there similar to New York’s.

“Well, every state has a unique process,” Wasserman says. “And New York entered uncharted waters in 2014 by passing a constitutional amendment that supposedly was going to hand over power to a bipartisan commission. Most New York politicos, on both sides of the aisle, would agree that it was designed to fail, because most successful commissions have at least some tie-breaking component or independent component to them. New York’s did not. And so the Democratic supermajority, unsurprisingly, took over the process after the commission failed.

“What’s at issue now,” he adds, “is whether the Democratic map violates the anti-gerrymandering provisions of that 2014 reform. And that’s up to state courts to decide.”

Given that state courts will be the decision makers, there will likely be different outcomes for similar-seeming cases. There are ten states where independent or bipartisan commissions have final authority on redistricting. Wasserman doesn’t include New York in that group, since the legislature has always retained its veto power over the commission process.

“In North Carolina and Ohio,” he says, “state supreme courts threw out Republican-drawn maps on the basis that they violated state constitutional provisions. Ohio’s constitution is fairly explicit that maps must not unduly favor parties or incumbents. North Carolina’s constitution doesn’t have explicit language regarding gerrymandering, but Democrats hold the majority and interpreted the constitution to mean that the Republican plan violated voters’ rights by effectively diluting votes.

“New York’s constitutional language,” he adds, “is much more similar to Ohio’s. And so, if the same standard were being applied in New York as was the case in Ohio, then New York’s Democratic map would be struck down. There’s no question it unduly favors Democrats — they are poised to win 22 of 26 seats in the state, despite routinely winning only 60 percent to two-thirds of the vote.”

As is evident from Assemblyman Zebrowski’s statement, he says, Democrats will try to make the case that they drew the maps on the basis of keeping communities of interest together, rather than on the basis of partisanship.

“We’ll see if judges believe it,” Wasserman says.

Regarding Nadler’s district specifically, he observes, “There’s no commonality between those two [areas], but with this map that was proposed, it seems like they went into overdrive in order to connect these two places.”

Indeed, one of the curiouser reasons given in testimony to the redistricting commission for keeping Boro Park in Nadler’s district was that the late Bobover Rebbe, Rav Shlomo Halberstam ztz”l, had a shul on the West Side before he moved to Boro Park. That has nothing to do with the neighborhood he left behind, of course, but the commission apparently accepted the argument.

New York’s criteria say that lines can’t be drawn to favor a party or incumbents, but the term “community of interest” is a fairly flexible term, Wasserman notes. The parties can make an argument that far-flung communities in awkwardly shaped districts constitute communities of interest.

“There are a lot of competing criteria, and a lot of competing considerations from state to state,” he says, “including compactness, communities of interest, racial and ethnic composition — and of course partisanship.”

So, Has He Seen Enough?

Wasserman’s business being polling, his own standing rises and falls along with the public perception of the survey industry — which has absorbed blow after blow in recent years. Donald Trump did not lose in the landslide that was predicted in 2020. Joe Biden did not get the double-digit victory that NPR claimed he would. The Washington Post’s prediction of Biden winning Wisconsin by 17 points was off by, oh, 16 points.

Polling’s problem is international in scope. The buzz in Israel’s 2018 Knesset election was the nail-bitingly close race between the right-wing Likud and the leftist Zionist Union. In the end, the Likud ended up with 30 mandates, while the Zionist Union flamed out with only 24 seats. Similarly, UK pollsters forecast that the Scottish independence referendum that year would end that country’s 300-year-old marriage with England. All talk of an unceremonious divorce fizzled when a 55-44 defeat for independence put them out to pasture.

Wasserman divulges that he now places less weight on polls, and relies instead on the cold facts of voting outcomes in the little-noticed special elections that occur regularly around the country.

“Clearly,” Wasserman says, “polling missed a sizable segment of the electorate in 2020, more so than in 2016. And we have to grapple with the reality that there is an asymmetric bias in who is willing to take a poll. And frankly, that’s why I’ve become more reliant on hard election data from special elections that don’t get much coverage, than on polling at the national or district level of horse races. Because we can tell who’s voting from election results, but we can’t tell who’s going to show up for polls.”

Somewhere, in some race some time ago, Wasserman uttered the phrase that vaulted him to instant recognition. He was following a race and, based on the data and demographics of the district, he decided he’d seen enough and did not need to wait for the outcome.

“I’ve seen enough,” he tweeted, predicting the winner.

“I said it once back in, I don’t know, 2013 or 2014, and it just kind of took off from there,” he says with a laugh. “I’m not even sure how it did, but it caught on.”

Did he ever think of monetizing it, perhaps by selling “I’ve seen enough” merch?

“I’ve sold a few mugs for charity,” he acknowledges, “but that’s about it.”

In the meantime, Wasserman is happy with his job, delving into minutiae for every district in the country. He’s seen enough, but has yet to have had enough.

“One day,” he predicts, “I will have seen enough of politics.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 900)

Oops! We could not locate your form.