Nothing Plain in Sight

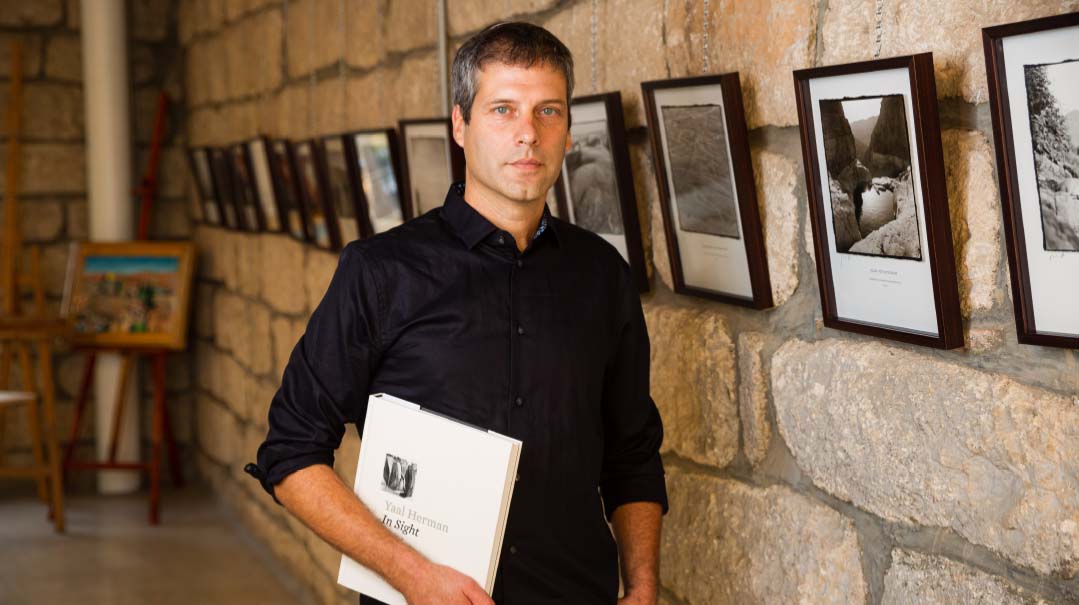

In Sight is Yaal Herman's newest project, his “Covid baby,” and it’s one of the reasons I came to visit. It was worth the trip

Photos: Elchanan Kotler

Passing through the gate leading into Hutzot Hayotzer Artist’s Colony is like entering a parallel universe. The dust and noise of a Jerusalem under constant construction falls away to be replaced by a calm, still serenity. The stone steps leading down to the galleries are picturesque, and I’m sure the lush green surroundings and trickling fountain add to the resident artists’ inspiration. I know I’d be able to write here all day.

The plaque with Yaal Herman’s name is right there on the left; I duck into the curved stone room and am instantly surrounded on all sides by striking photos.

“Shalom,” Yaal says, smiling calmly. “Welcome to my studio.”

I look around, but Mishpacha’s Elchanan Kotler is nowhere to be seen.

“Where’s the photographer?” I ask, putting down my bag.

“I am the photographer,” he says.

“Oh. No, the other one, from the magazine.”

“Ah, I don’t know.”

I reach out to his desk to take a business card. These aren’t regular cards — each features a different photo on the front, colored in grays and whites.

“Choose which one you’d like,” he says.

I sift through until I find one of a bridge submerged in the sea. It’s beautiful, and peaceful, and just a bit eerie.

“Ein zeh ki im beis Elokim v’zeh shaar haShamayim,” Yaal quotes. “You can read more about it in the book.”

The book, In Sight, is Yaal’s newest project, his “Covid baby,” and it’s one of the reasons I came to visit. It was worth the trip. The book itself is an elegant piece, printed in Italy, and the works inside are outstanding. Each spread has a bordered, black-and-white photo, and on the facing page, a connecting verse and thought, almost a devar Torah, somehow marrying the mundane to the metaphysical.

“How did this happen?” I ask, gently flipping through the pages. “Did inspiration strike while taking photos, or did you match photos with divrei Torah that inspired you?”

Yaal laughs. “That’s the question I get most often: ‘What came first — the image or the verse?’ The answer is one, or the other, or both at the same time. There are images I spent years looking for to illustrate an idea, and there were other times when the image was simply there just waiting for me to capture it.”

“Still,” I insist, “it’s unusual for a photographer to view the world through the lens of Torah.”

“Around ten years ago,” Yaal shares, “I had the pleasure of visiting with Dr. Ernie Seidman a”h in his Montreal home. Ernie showed me a Kabbalah art piece that he had purchased on a trip to Morocco, and he took the time to interpret the mystical concepts portrayed in the artwork. I was intrigued — both by the explanation and by the idea of art as a trigger for a thoughtful discussion.”

The first five images in In Sight were created during the year that followed his visit to Montreal. They served as prototypes for how the photos would be printed and framed; each was sold with a simple explanatory page attached.

Nearly a decade later, there was no space left on Yaal’s gallery wall, and the explanatory text ran to almost 70 pages long.

“I realized that this overflow could be bound in a more inclusive format, such as a book. Browsing through negatives from earlier periods in my life, I discovered that not only did I use similar camera formats and film stocks, but I was also creating images that resonate with biblical passages.

“Covid lockdown was a great time to work on the book. I was already running an in-house photography course for my five children, Asher (Ashi), Shmaya, Roey, Yonadav, and Avigayle, each one talented in their own way. We toured and camped when we could, and the last photographs in the book were taken during these months.”

I smile at the thought of five little people spending lockdown learning about photography. In my house, it had been more of a survival-of-the-fittest situation.

“And why’d you pick the title?” I ask, intrigued.

“The word ‘Insight’ is short for internal sight,” says the photographer. “It may also refer to what is on location — ‘in sight,’ but it hints at what is obscured from our perception and the mind’s eye. My children assisted in lending me their perspective. Simi Peters, a close family friend from Har Nof, teacher and author of Learning to Read Midrash, took my ideas and phrased them as what she describes as ‘English.’ Rabbi Dr. Chananya Blass, with whom I studied Tanach for over a decade, wrote the introduction.”

Meanwhile, on the Kibbutz

There’s a large photo on the wall of the profile of a woman riding an open air car. There’s something visceral about it, I can practically feel the air rushing by.

“The kibbutz,” Yaal says simply. “That’s where I had my first encounter with photography. I was in ninth grade, and I came up with a biology project that examined the effect of light intensity on algae in a nearby stream. A great excuse to spend school time outdoors. For the project, I borrowed a light meter from my uncle Hanoch, a photography enthusiast.

“My next biology project had to do with the kestrel’s habit of hiding food, for which Uncle Hanoch lent me his old Pentax camera. About the same time, I was lucky to meet Moses — a classmate’s father — who was kind enough to teach me the fundamentals of photography. We’ve kept up a close friendship ever since.

“Having access to a readily available professional darkroom, a privilege offered by our kibbutz, was both a dream and a magnet. I would often go there in the evening and spend the entire night squeezing all I could out of a single negative.”

“And you already decided you would be a photographer back then?”

Yaal thinks about this. “I once heard that a person’s life is like a train ride — the stops are already set, you have to travel through them. I think one of the stops, between ages 14 and 16 usually, is professional identity. You know when you’ve reached it. And I suppose for me, it was photography, as well as music and being a guide.”

The darkroom and the isolation from the outside world was Yaal’s first step forward into the identity of an artist. His first photography exhibition included Cibachrome color prints of local birds; the next two exhibitions were in black and white and included photographs of friends and classmates posed in nature.

I ask him about life on the kibbutz; was it as strange as it sounds to outsiders?

“To me,” Yaal says, “it was life. My father comes from Dublin. He came to the kibbutz to do ulpan, and he met my mother there. We did not speak English at home, out of respect for our Zionism. My mother was a born-kibbutznik, but her family was originally from Stuttgart and Mannheim, Germany. I grew up in a children’s home — children lived with their friends on the kibbutz.”

“All in all,” Yaal says, “I feel very grateful for my upbringing, for both by my parents, with whom we spent every afternoon and Shabbat, and for the kibbutz, Kibbutz HaZore’a, and its residents, who taught and enabled me to learn and explore in a way that not many societies do.”

A New Man

Putting down In Sight, I look at the calm, successful man in front of me.

“No, I don’t have traumatic memories from then,” he says, answering my unasked question. “but I am aware that there is a trauma. Our children’s home was called the ‘cheder,’ and our parents’ home was called the ‘bayit.’ Some other kibbutzim had the opposite, and three generations earlier, some of the children didn’t even know who their birth parents were.”

“Why?” I know it’s barely a question at all, but I want to know what would make a group of people think it’s a good idea to separate children from their parents.

Yaal passes me several plastic-wrapped photos and settles back. “It’s an ideology, a religion unto itself. Equality, socialism, communism to the ultimate degree. It’s a concept built on need and value rather than greed and ambition. A concept built to establish a ‘new man.’ It had its merits. Imagine a janitor and a manager making the same amount of money. The currency is not financial — it’s in relationships, self-esteem, and social appreciation.”

I look down at the photo in my hand. A group of people, smiles on their faces, bent over something hidden from the camera.

“What are they seeing?” I ask. From their smiles, I’m guessing it’s something wonderful, and I’m curious.

“That’s the first baby born on the kibbutz. ‘It takes a village’ takes on a whole new meaning here. She was everyone’s baby, because what is brought onto the kibbutz belongs to everyone, equally. A man on the kibbutz I’m from played the lottery and won a few million shekels. He gave it all to the kibbutz. He eventually left a few years later — he didn’t receive a shekel from his winnings. That was the internal law — the ‘takanon.’ The kibbutz owned the belongings, yet it was also the kibbutz’s responsibility to raise the children.

“I remember the day my father and I loaded a small wagon with a brand-new television set. If you’d looked to the right or to the left, you would have seen other families on the kibbutz wheeling their brand-new televisions, the exact same model, up the hill to their homes in the exact same wagon, setting it on the same television stand in the living room.

“It was something out of a dystopian book. But I don’t believe the kibbutz ideology is wrong, per se, just taken too far. As America has taken capitalism too far.”

My Soul Knew

I open Yaal’s book again and drink in a photo of Bircas Kohanim at the Kosel. “How’d you go from being a young boy in the kibbutz darkroom to someone who can capture such a sight?”

“When I was living on the kibbutz, my hair was cut military style. Yet for some reason, before I ate, I would scoop my hands behind my ears. Only years later did I realize I was making the motions of peyot. My hands knew what my mind did not, something from a previous life.”

Elchanan Kotler, magazine photographer, shows up then. The conversation quickly switches to shop talk, and I have time to walk around and examine more photos. There’s a 3D photo of Rechov Yafo that I can’t take my eyes off of. The scene moves as I step backward and forward, the bustle of humanity springing to life, yet muted in a fantastical way.

“You can’t imagine how many times I had to revisit that one spot to get the photos necessary for that,” Yaal says, when he notices what’s captured my attention.

“Did they think you were a terrorist?” I ask, only half-joking.

“With my tripod case? Possibly.”

My Bar Mitzvah Decade

“How did you go from hard-core kibbutznik to shomer Torah u’mitzvos?”

“Well, it wasn’t foreign to me. My grandma was frum, and my dad isn’t religious, but he doesn’t work on Shabbat.”

The kibbutz had a Reform style for religious rituals, Yaal explains, like one Seder table set for the 800 kibbutz members and guests.

“There was matzah next to baskets of bread, so everyone could make their own choices. There was a giant succah, but under a roof. Our bar mitzvah year was celebrated with missions of courage, self-actualization, and contribution to the community. We also learned Tanach — but in the back were chapters of the New Testament.”

I’m speechless at this revelation; Yaal continues.

“Becoming frum was a process of course, as anyone’s baal teshuvah journey is. From when I was 20 until I was 30, I experienced what I called ‘my bar mitzvah decade.’ In a way, the visual composition you are holding can be viewed as a dot-to-dot drawing of a road trip from Karl Marx to Moses. I had just finished my military service and had experienced throughout what I was only able to call Hashgachah pratis. I saw it, and I wanted to know more. There were too many connections and coincidences… I set off to discover what it all was. On the path to ‘zen,’ I studied about spirituality and ended up in Aix-les-Bains, France, living with a man named Reuven Zarad, a tzaddik, scholar, and baal chesed. I instantly fell in love with the Ramchal — I just connected with his teachings.”

“You speak French?”

“No. Reuven and I communicated through Mishnaic Hebrew.”

I laugh, picturing this. “What about your wife? Is she also a baalas teshuvah?”

Betty Herman is the founder and director of Hevlei Kesher, Yaal briefs me, a program present in all of the Tipat Chalav baby wellness clinics around Jerusalem, dedicated to providing support and services to mothers and their families who are impacted by perinatal mental health issues.

“Betty grew up in a very spiritual home in Montreal that provided less of a focus on practical halachah.”

My Main Muse

The Land of Israel has been his source of inspiration since childhood, the photographer shares. He used to work as a tour guide and later on as a guide for photography tours and has always been inspired by the multitude and abundance of everything this land has to offer.

“The less-traveled sites and themes, the dirt roads, and narrow trails are what intrigue me the most.”

“When did you make a name for yourself in the photography world?” I ask, wondering how long it takes to go from wandering the world to having your own gallery.

He takes me on a narrative tour. “Well, I took classes with specific professors whose works I appreciated. I learned so much from them, and I’m still in touch with some of them.”

He describes a long duration during which he worked printing out negatives in darkrooms, sometimes producing huge, five-meter prints, testing to get the color and density correct.

“Until today I love the old printing techniques, matching, mixing salts, real cotton paper,” he says. “It’s ‘back to the basics’ in the best way.”

He moved to New York for a while, working as a framer. Then he spent a decade working in multimedia, using electronic code, until he decided he had enough of the virtual and was ready to go back to making real world prints.

“And now, I am currently working as a full-time photographer,” Yaal says. “I relish the challenge of finding solutions to technical and aesthetic problems, often using studio lighting and digital manipulations to address them. Aside from gallery work I photograph commercially — real estate, products and love outdoors family portraits.”

For the photos in his book, Yaal reached back into his toolbox of old-school techniques.

“The medium for capturing the In Sight images was a traditional, mechanical-chemical, monochrome process. Nearly all the images in this book were captured using the purist ‘full frame’ approach. The printed image includes the frame’s mechanical border as exposed in the camera — letting the strict limitations of the medium channel growth and conceptual creativity.”

And although I understand little of the lingo, my takeaway is that Yaal believes in a real, tangible print. And his book is his way of sharing them with the world.

Focused

“Tell me about some of these photos,” I request, cracking open In Sight to a random page.

He peers at it. “That one is Soul Candles.”

I look at the exquisite photo — it looks painted, not captured.

“It is a sad part of history,” he explains. “Israel was under Ottoman rule for about 400 years, and the people living in the Old City of Jerusalem suffered terribly. Poverty was rampant, sickness and starvation prevalent. Only two out of eleven children born would make it to one year old. Life expectancy in general was only 45 years old, and the girls would marry at 12 — just to have Jewish continuity. The mesirus nefesh these generations had is on another scale. Their dowry could be one cotton dress and two dresses made of rice sacks.

“Death was a part of everyday life, yet no one could afford a proper burial. A man named Sambuski donated a large piece of land”—Yaal taps the photo, indicating—“and they buried the dead there. Since most could not afford a tombstone, they marked the burial location with a bulb of a squill, under the head of the deceased. And when they bloom, every year around Succos, they become soul candles.”

Sad. I flip to another. “And this one?”

A tree rooted in a cistern, holding thin branches out to the desert, yet spreading out magnificent thick roots in the soil below.

Yaal smiles. “That is the baal teshuvah. To the passerby in the desert, there are just a few branches. But to those who see below, there is deep growth. B’makom shebaalei teshuvah omdim, tzaddikim gemurim einam yecholim laamod.”

I flip through the rest, mesmerized. “Which one took the most time to get right?”

“Surprisingly, the one image that took the most attempts to capture,” Yaal shares, “was from Psalm 1: ‘Like a tree planted by streams of water that yields its fruit in its season.’ Although such images are widely available in northern Israel, I must have had a hundred exposures from ten different locations for this one verse. It was only with the last developing batch, ‘one last trip’ to the northern Snir River, to that same specific tree trunk, when the light and the air finally agreed with the lens.”

Up Close

Yaal passes me two more copies of the book.

“Choose your cover,” he says simply.

I’m touched that I get to take something so beautiful home with me. I examine the window in the white cover closely; each one frames a different photo.

“This one,” I say at last.

The photo I chose resembles a biology slide; something is magnified and alive, and I know that whatever Yaal’s answer is, it will surprise me.

“That is believed to be an aura,” he says.

Yup, did not see that one coming.

“We all give off electrical discharges, our auras, so to speak. And Kirlian photography is believed to be able to capture them. As we read in parshat Bereishit, Hashem blew a nefesh chayah into Adam, a sort of electrical charge, and he came to life.”

Definitely not a biology slide.

He places the book in a bag for me. “These are the lessons I learn out in the world with my camera. And I hope my publication serves its viewers as a reminder of all that is hidden from the eye, yet familiar to the soul.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 896)

Oops! We could not locate your form.