Mounting Troubles on Temple Mount

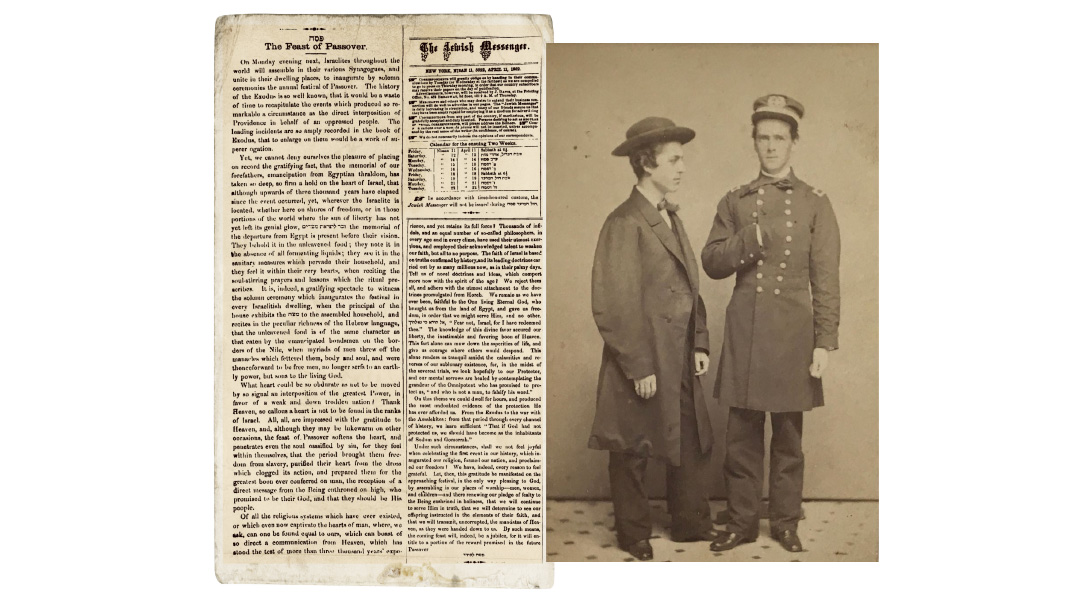

| September 20, 2022While Jews were banned from the Temple Mount for centuries, there are both legends and credible accounts of those who defied the rule

Title: Mounting Troubles on Temple Mount

Location: Jerusalem

Document: Circular

Time: 1920

For centuries following the 1517 Ottoman conquest of Jerusalem, the sultans forbade non-Muslims entry to Har Habayis. Evidence suggests the Ottomans went so far as to ban the small Jewish population from as much as even viewing the holiest of sites, and those caught doing so were punished.

In 1839, the Ottoman government promulgated sweeping reforms throughout the empire known as the Tanzimat. These social, economic, and political reforms modernized banking and the military, and granted more civil liberties to the general populace and equal rights to non-Muslims. Tanzimat granted non-Muslims the right to ascend al-Haram al-Sharif (the Arabic term for the Temple Mount), and several prominent Christians made the pilgrimage.

The growing Jewish population followed the ruling of Rav Yisrael of Shklov, who held that Jews were permitted to enter the Temple Mount only in certain areas —the exact locations of which were in dispute, effectively barring any ascent. There were, however, some notable exceptions.

On an 1855 visit to Jerusalem, Sir Moses and Lady Judith Montefiore joined British consul James Finn on a visit to the Temple Mount. Montefiore was carried across the site by Muslims in a sedan chair, which he felt alleviated the issue of setting foot on the Temple Mount. Though the Muslim authorities didn’t express any opposition, the rabbinical leaders of the Old Yishuv protested the act as a contravention of halachah. This brought the halachic issue of Jews visiting Har Habayis to the forefront of history.

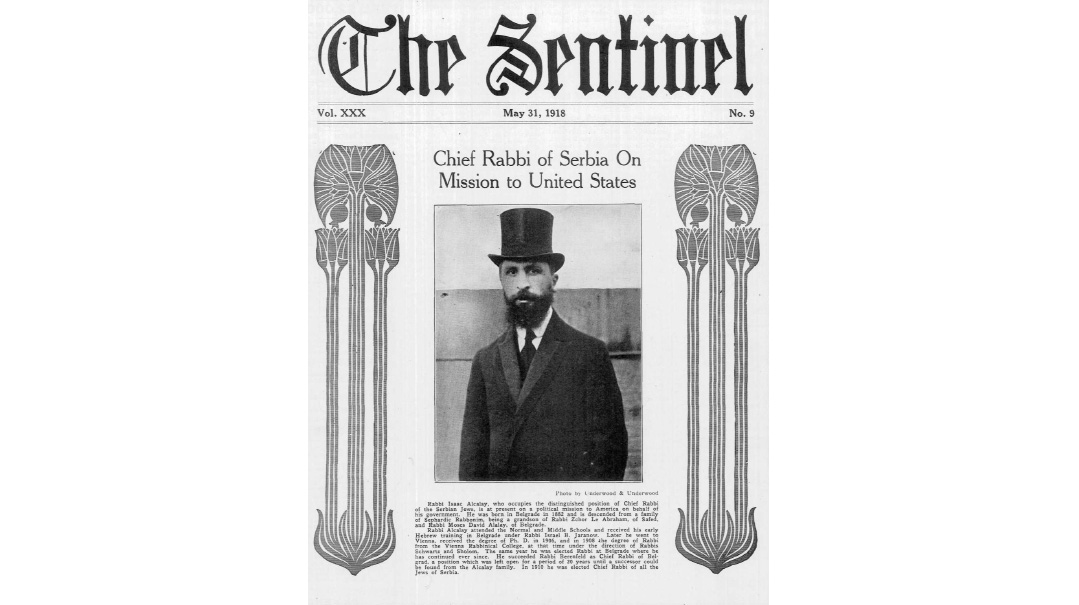

In 1919, Rav Avraham Yitzchak Kook was appointed to fill the post of rabbi of Jerusalem, which had been vacant for a decade following the passing of Rav Shmuel Salant in 1909. His appointment was recognized by the British Mandatory government, who further authorized his appointment as the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Eretz Yisrael in 1921.

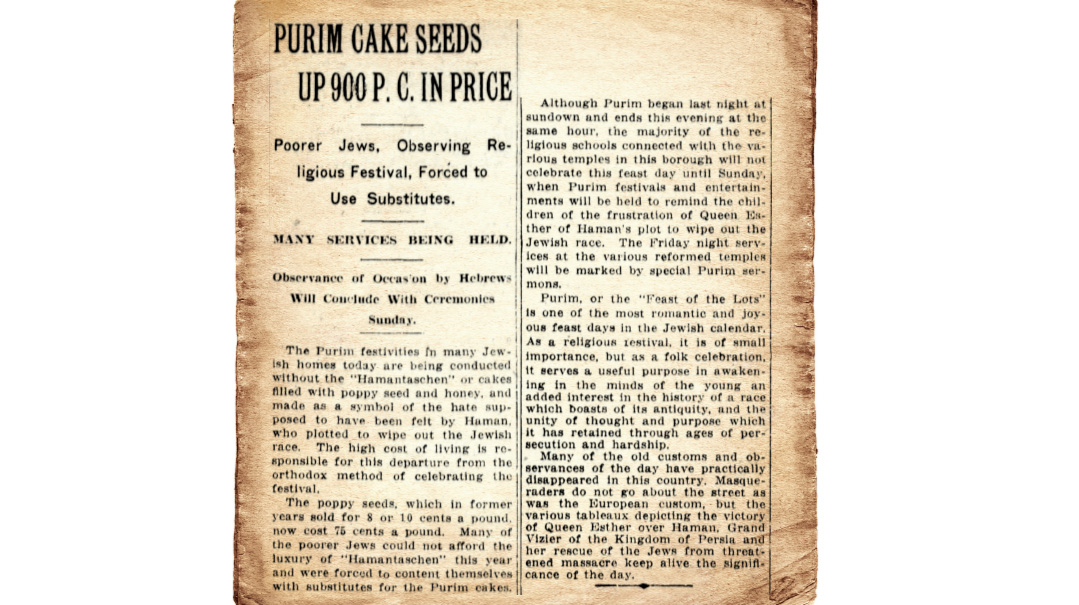

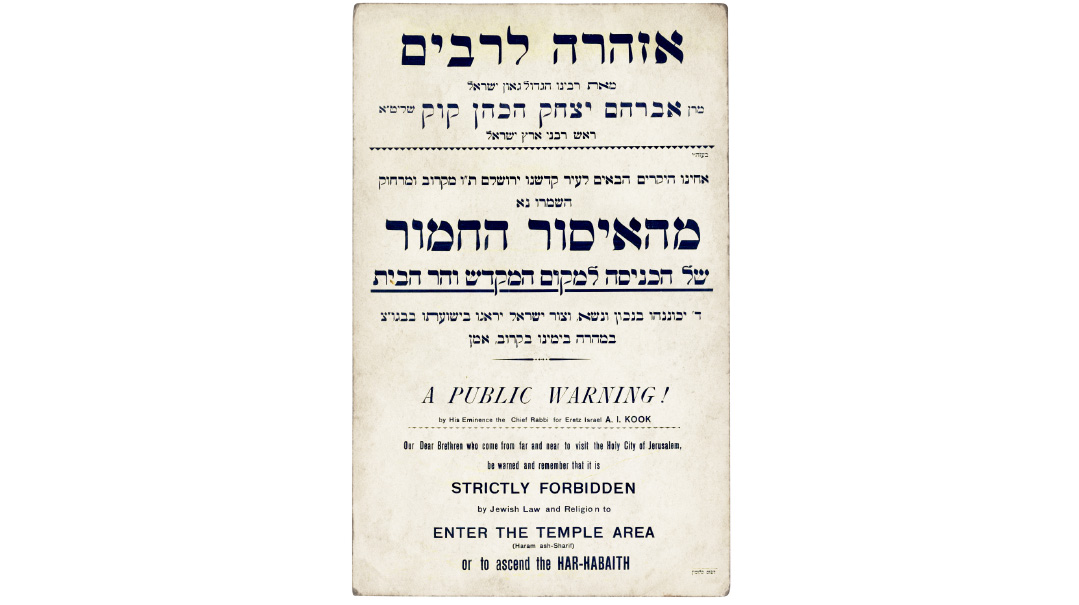

Rav Kook had a long history of opposing any ascent to Har Habayis due to halachic concerns. When Baron Edmond de Rothschild visited the Temple area on a visit to the country, Rav Kook duly registered his protest. He occasionally published his unequivocal view, “that it is strictly forbidden by Jewish Law and Religion to enter the Temple area or to ascend Har Habaith.” He’d periodically have signs placed around town prior to the Yamim Tovim reiterating his opinion on the matter, especially as tourism picked up following World War I.

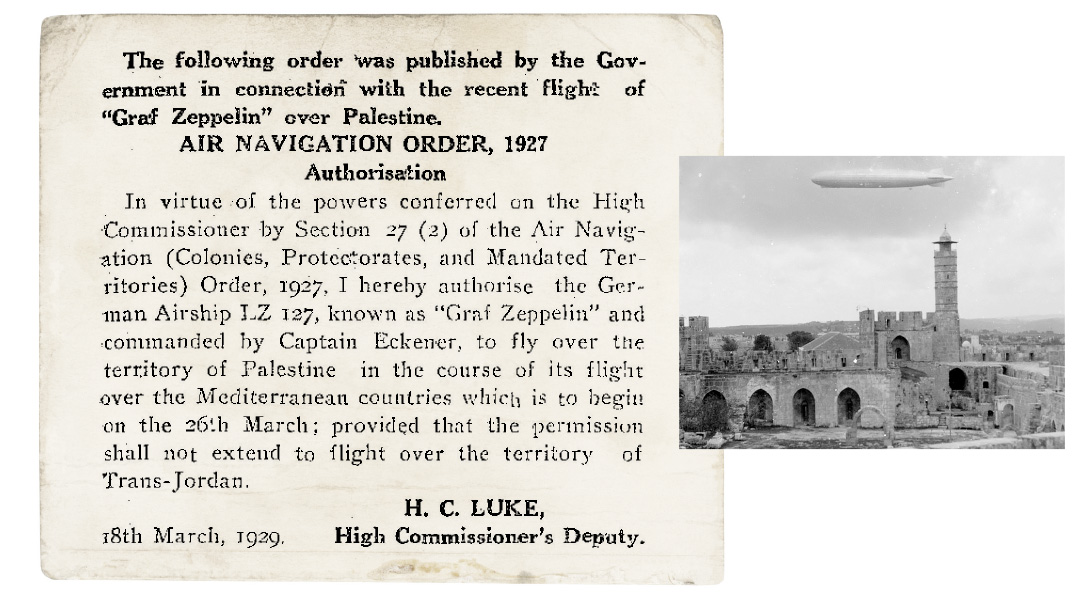

The late 1920s saw the rise of Arab nationalism across Eretz Yisrael, which culminated in the devastating pogroms in the summer of 1929 in Jerusalem, Chevron, Tzfas, and other locales. One of the catalysts of the bloodshed was a dispute over control of the Kosel. As a result of the Palestine Riots, the Mandatory government extended the Jerusalem Islamic Waqf’s control over the Kosel area, in addition to the Temple Mount complex, while Jews were allowed access to the Kosel to engage in prayer. Another byproduct of the riots was that the Waqf prohibited Jewish entry to the Temple Mount from then on.

Preparing to Return

In preparation for the advent of the Messianic era, Rav Kook opened a unique yeshivah named Toras Kohanim to engage in the study of Kodashim. It opened its doors in 1920 in the courtyard of the Chayei Olam Yeshivah in the Muslim Quarter of the Old City, and Kohanim were invited to join its ranks to familiarize themselves with the relevant halachos. Though Rav Kook soon departed to found his own visionary yeshivah of Merkaz Harav, Toras Kohanim flourished for quite some time thereafter.

Pity from the Pasha

While Jews were banned from the Temple Mount for centuries, there are both legends and credible accounts of those who defied the rule. In 1833, a young Jew clandestinely made his way up to the Al-Aqsa Mosque and spent the night there, intent on destroying as much as he could. When the morning came and guards saw the broken windows and fixtures, they searched the compound and discovered the youth, dragged him off to prison, and began to torture him mercilessly. They then petitioned Mahmud Ali Pasha of Egypt to approve the usual punishment, burning him at the stake. To their great surprise, Ali Pasha wrote that the guards were the ones liable for punishment because of their carelessness. As per the Jew, he ordered him to be set free — in defiance of the law that non-Muslims who desecrate the sanctity of the Mount be punished by death, explaining that because Jews are also circumcised, they are not subject to the death penalty.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 929)

Oops! We could not locate your form.