Members of the Tribe

In the African backwoods, Ari and Ari meet natives aspiring to be Jews

Photos: Ari Greenspan

In keeping up with our halachic adventures, Ari Zivotofsky and I try to visit off-the-beaten-track Jewish communities regularly. But while Covid put a huge dent in our travels, we did receive a plea last year from the Jewish community in Nairobi, Kenya, to come and help provide them with kosher meat and chickens for Pesach, as their supply from previous shechitahs had dwindled.

The bylaws of Nairobi’s Hebrew Congregation — the 100-year-old synagogue in the capital that serves Jewish ex-pats from Israel and Europe living in Kenya, along with white Kenyans whose forbears arrived a century ago — require that only kosher food be used for shul functions, and the only way for them to have reasonably priced meat is to bring in a shochet. I’ve done it for them gratis the past few rounds, which is my pleasure: They fly us to Africa and then we have the opportunity to visit some fascinating enclaves most people have never heard of. (On one of these trips, I decided to go on a gorilla Safari, when I was summoned by a Chabad shaliach for a local British woman whose baby needed a bris.)

We planned our trip for the week before Pesach, but just then Kenya went into lockdown and we had to delay it and rescheduled for the summer. This time, due to several technical factors, I went solo.

As we all know, in order to travel from Israel, you needed a Covid test before you departed and before you got on the plane back to Israel. That’s generally not a problem in Western countries, but when we asked one of our African Jewish friends in Tanzania how we could get a test so we could fly home, he calmed us down. “No problem,” he said. “We have a lab here in Arusha, just pay and I can guarantee you a negative result.”

One of the goals of this last trip, aside from helping out the Nairobi community, was to visit a small, relatively new emerging Jewish-identified community in Kasuku, in the rural highlands. This “emerging” community is one of the many groups around the world who have left Christianity and have announced themselves as being Jewish. While they are certainly not halachically Jewish, their devotion to mitzvos and Torah learning is inspiring. There are pockets of such communities all over Africa, which is a fascinating topic in and of itself.

What’s driving these former Christians, who’ve decided to throw in their lot with the Jews? Without a doubt, the Internet and its wide access — even in rural locations — is responsible for the lion’s share of East Africa’s emerging communities — we call it “YouTube Judaism.” Today, many of these people listen to shiurim in English, and some even have an online chavrusa. Today, a rabbi in Brooklyn can learn with an Igbo tribesman in rural Nigeria and answer the questions that would never have been explained before.

While generally there is an understood prohibition about teaching Torah to non-Jews, in the last 200 years many poskim have been lenient — including Rav Ovadiah Yosef and Rav Moshe Feinstein — primarily regarding individuals who want to learn. (The Rambam ruled that one may teach Torah to Christians but not Muslims, as Christians accept the Divine authority of Tanach). What about today’s phenomenon, when entire communities — in Africa, South America, and other venues — want to take on Jewish practice and have been learning about Judaism for years, often on a hopeful, although not always realistic, path to conversion? We’ve discussed it with rabbanim who’ve given us specific direction in individual cases.

A visit to these communities stirs the imagination. Who would think that in an isolated African village on a lonely mountaintop there would be a congregation of men wearing yarmulkes and davening with a “minyan”?

But here we were, in the land of the Kikuyu tribe, with about 15 families centered in the small village of Kasuku. This community had once been part of Kenya’s Messianic Jewish Church network (basically a Christian church, dressed up to look like a shul with no crosses but lots of Magen Davids), until they split off.

The church’s beliefs are a bit mixed up — most of them see themselves as Christian and Jewish at the same time. This particular messianic group has 50 branches all over Kenya and over 8,000 members. Not understanding this can be confusing for a visitor entering one of their compounds; one can be thrown off by the plethora of Jewish stars, the Herzl social hall, and a sign pointing to the synagogue.

But feeling an affinity to Judaism and the Old Testament sometimes raises profound philosophical questions for thoughtful Christian members — concerns like, “If the founder of our religion kept kosher, Shabbat, and mitzvot, why don’t we?” Often, these members wonder why they should be Christian and not Jewish. And then, rebuffed by the church leadership, they begin to navigate on their own.

That’s what happened to the congregation in Kasuku. A group of families in the church began studying the Old Testament, rejected the New, and decided they wanted to become part of the authentic Chosen People.

A Jew-loving oasis in the African highlands. A Magen David theme and Israeli blue and white colors peek out of the rolling green hills. (Left) Even this little restaurant hut shows how Israel is venerated in these parts. (Right) The split-off Kasuku community wanted a true Jewish direction, not a mixed-up messianic theology

The Breakaway

In Kasuku, Kenya

Yehudah Kimani — whose father and his friends left the church, began learning Torah, made a shul and a “minyan” and have a strong identity as part of the Jewish People — is the current leader of the Kasuku congregation, and he piqued our curiosity. We’ve been in touch with him for two years and were trying to figure out how to visit: Not only was Kenya in complete lockdown daily from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m., but the country was sliced into districts with travel prohibited between them. But Yehudah told us it was no problem. “I regularly travel between districts. You just need to give the soldier at the roadblock some money and you can get through.” Luckily, the day before our planned trip to visit the group, the travel ban was lifted.

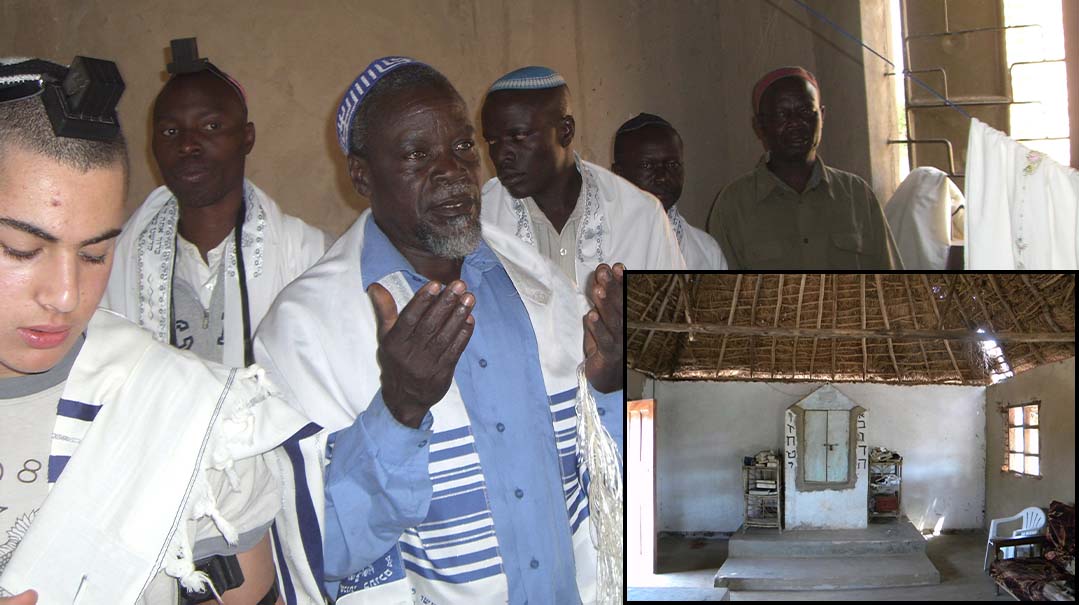

We arrived at Kasuku and weren’t disappointed. Between two houses was a large Magen David and a menorah statue. A sign said that we had arrived at the synagogue and even listed times for a daily minyan. We noticed a dilapidated clear plastic succah in the next field, and in the distance was a building with men wearing kippot and some women waiting for our arrival, all standing in front of the “Simchat Torah Beit Medrash” sign.

The tiny Kenyan community practices its own style of Judaism, helped along by some books and religious articles donated by sympathetic members of the Nairobi Hebrew Congregation.

I was curious about how this community developed, and so I arranged to meet with the “rabbi” of the messianic church from whence this group of devout mityahadim of Kasuku arose. Despite a prodigious number of Jewish symbols and wall hangings, giving the sense of a rabbi’s study, I discovered that this “rabbi” really didn’t know anything of substance about Judaism. Menorahs and Seder trays, and little paper Torah scrolls, hamsas and Israeli flags adorned the walls. There was even a picture of Rav Mordechai Eliyahu ztz”l on the wall. One thing that was a bit troubling was a kind of hostel, a free lodging for Jewish kids traveling around Kenya to stay in. The Israelis fixed it up, painted the walls, and wrote their names in Hebrew. An unsuspecting traveler could easily be taken in by the apparent Jewish environment and find himself tempted by another religion without even realizing it.

After Yehudah’s father and other like-minded worshippers decided they wanted real Judaism, Wanjiku, the most “Jewish” of her former breakaway group, guided them in Jewish practice as best she knew

Yehudah Kimani’s small community, however, saw the difference between the two religions and broke away from Christianity. But how does an isolated African coterie, with little Internet access and sporadic electricity on a hilltop in Kenya learn more about Judaism? Part of the answer is connected to a special Kenyan woman by the name of Wanjiku, who was part of the original messianic community and also had left Christianity together with Yehudah’s father and a few others.

Wanjiku moved to Nairobi to be closer to a real Jewish community, and came weekly to the Orthodox shul in the capital, although, as a black villager who came from a Christian sect, she was less than welcome. Still, she persevered, coming to services weekly with utter devotion to Yiddishkeit despite all of her hurdles. She was poor, living in a cement room with no running water or a bathroom. She lived too far to walk to shul, so she would come before Shabbat and spend the night dozing in hotel lobbies until she was kicked out, moving to another one until the morning prayers. Wanjiku’s dream was to undergo an Orthodox conversion, something very unlikely given her circumstances.

We’d met her years back on one of our African trips, and a few years later she contacted us and told us that she was losing her vision and that no doctor in Kenya was willing to perform cataract surgery on her. Ari Zivotofsky and I helped her get free surgery in Shaare Zedek, and while recovering, she stayed in our home for three months. Wanjiku went to the Kosel daily and sat there for hours. When she was in our house, she kept herself busy reading Tehillim and attending shiurim. Wanjiku, as the most “Jewish” of her former group, kept in touch with them and guided them in Jewish practice as best she knew.

(Left) Although most of the original community went underground, Yehudah Kahalani made it his life’s mission to keep the hidden Yemenite traditions alive. One stipulation for the shul: no driving on Shabbos (Right)In a small Christian cemetery near Arusha for Polish refugees from WWII who’d settled in East Africa, Yehudah and his brother Shimon point to four Jewish graves blocked off in a corner. While some members of Yehudah’s community have moved to more established places, as long as he’s needed, he’s staying put

Keeping the Promise

In Arusha, Tanzania

While Yehudah Kimani understands that he’s far from being considered a halachic Jew, we’ve also remained in touch with another Yehudah — Yehudah Kahalani, a Yemenite leader of a small Jewish enclave in the neighboring Tanzanian region of Arusha. It was his father and grandfather, both well-versed in the Yemenite traditions of his ancestors, who charged Yehudah with a mission before he died in 2010: Keep your Judaism alive.

But how did these elderly Yemenite Jews, who unflinchingly maintained their ancestors’ traditions, manage to stay under the radar all these years in Tanzania of all places? There was a little-known community of Yemenite Jews that crossed over the Gulf of Aden into East Africa in the 1880s. Some of them went south through Ethiopia and Kenya and settled in present-day Tanzania, searching for financial opportunity. There they met up with Ethiopian and Moroccan Jews who’d also migrated south. Later, in the 1930s, a number of Polish Jewish refugees added to the number of Jews in the area. According to Yehudah, his own Yemenite ancestors came to Arusha from the Tanzanian offshore island of Zanzibar, where they’d set themselves up as traders.

Yemenites are famed for passing on their traditions, and that’s what happened on the outskirts of Arusha: Hidden in the verdant African hills, in the shadow of the Kilimanjaro volcanoes, was their small synagogue. Due to surrounding hostilities though, the Jews kept a low profile, until the community was forced to scatter in response to aggressive missionary activity and religious persecutions in the 1960s, when the synagogue was destroyed and their sefer Torah burned. The instability, socialism, anti-Israel sentiments, and nationalization of land that came with Tanzania’s independence from Britain in 1961 prompted many Jews to leave the country, and those who remained were forced underground and kept their religious identity secret. Some of them even chose to live among the wandering Maasai tribe, where they felt safe and wouldn’t be spotted.

Some members of the older generation continued to practice Judaism in secret, hoping to one day have the freedom to rejoin their brethren out in the open. But many younger people didn’t even know their parents and grandparents were Jewish. All they knew was that their parents didn’t work on Saturday and were vegetarian.

Yehudah, a successful, well-connected lawyer as well as a lecturer at Mount Meru University, never had a formal education, but his father handed down the traditions as best he could. In recent years the Tanzanian government has become pro-Israel, and Yehudah felt comfortable coming out publicly as a Jew. Yehudah says there are many others like him, but they have either emigrated, assimilated, or are afraid to surface. (He recently told me that one of the country’s wealthiest men — and a practicing Muslim to the outside world — called him to ask what he should do for his daughter who is turning 12.) Still, Yehudah cannot forget the charge his father gave him to preserve the traditions, reunite the people, and restore the sefer Torah. And so, he purchased land on the outskirts of the city of Arusha, where the old shul used to be located, and today uses a good deal of his personal money for the sake of his little community. He has built a small shul and beis medrash, which draws up to 70 people on holidays, of whom he claims about 30 are “very religious and keep Shabbat” (although for most, their halachic Jewish status is questionable at best).

His community is extremely welcoming, but because he insists that no one is allowed to drive there on Shabbos or Yom Tov, he bought land adjacent to his house and sets up tents for his many Shabbos and holiday guests, while his wife Efrat does the cooking.

While some members of the community have relocated to larger, more established places, including Israel, Yehudah says that for now, for as long as the community needs him, he’s staying put. And to properly lead his people, he even reached out to “Partners in Torah” to arrange for a daily chavrusa. In addition, I give a weekly Zoom shiur to the group on Iggeret Teiman, the Rambam’s Epistle to Yemen, which gave hope to the Yemenite Jews mired in despondency and confusion as they faced extremist Muslim pressure on one hand and false messiahs on the other.

The Abayudaya took on Jewish traditions back in 1919, when their tribal leader came to believe that the real truth was what was written in the Torah

Hundred Years of Tradition

In Uganda

Next-door Uganda is home to another group, the more well-known Jewish-affiliated Abayudaya, whom we’ve visited on several of our African sojourns. The Abuyadaya, who had been converted to Christianity by missionaries at the end of the 1800s, took on Jewish traditions back in 1919, when their leader, Kakungulu, came to believe that the customs and laws described in the Torah were true. Soon after, a foreign Jew named Yosef arrived in their community and taught them about halachah and Yamim Tovim. In the 1970s, Uganda’s despot Idi Amin outlawed Jewish rituals and destroyed their synagogue, and while some converted to Christianity or Islam to avoid persecution, several hundred remained. They now number over a thousand strong in multiple communities, and their Jewish status, as well as the rabbi of their main branch, has been accepted by the Conservative Judaism movement. Some individuals within the Abayudaya have broken off and, while their halachic status is questionable, identify as Orthodox.

The group’s leader, Gershon Sizumu, a dynamic chief and former Parliament member, was ordained at the Conservative movement’s American Jewish University in California, and some members of Yehudah Kimani’s Kenyan Kasuku community have converted under his auspices. Sizomu opened a Jewish school and a “yeshivah” — which Yehudah Kimani attended — and whatever the community’s self-identification might be, they have ten synagogues around the country and a religious Jew would feel as if he had landed in something very similar to his own prayer services.

While it seems a bit unbelievable that there would be practicing Jewish-affiliated groups in the African boondocks, it’s a reflection of the recent sensation of Christian groups worldwide leaving Christianity and moving toward Judaism. There are probably millions of people moving from classic Christian doctrine in the direction of Yiddishkeit. The vast majority never make it all the way, but some actually do.

Hidden on the Coast

In Somalia and Sudan

Into this East African story walked Dr. Nancy Hartevelt Kobrin, a psychoanalyst, Arabist, and internationally renowned counterterrorist expert who has worked extensively with military, law enforcement, and mental health professionals in analyzing the psychological makeup of suicide bombers.

We met in her Tel Aviv home to discuss Jews in East Africa, with whom she developed a connection almost by accident, through her work. A little over a decade ago, Dr. Kobrin carried on a secret two-year ongoing email correspondence with a Jewish man and his mother living in Somalia, Kenya’s northeastern neighbor. They were part of a small, unknown Jewish community of Yemenites. His name was Rami, and his mother, Ashira Haybi, had been born in Taiz, Yemen, while his father was born in Aden.

Ashira supported her family with a textile business that she ran, and even did business with another Jewish woman in Djibouti who kept her Jewish identity a secret as well. (Ari Z. and I had actually been to Djibouti, a tiny Muslim country on the horn of Africa that also once had an Adenite Jewish community. We met with someone who we thought was the last Jew in the country, but it seems we were wrong.) Ashira kept a kosher home, kept Shabbos and mitzvos according to her ability, and raised Rami to do the same. They struggled mightily to observe their Judaism under the most extreme pressure and fear of discovery. Suddenly in 2008, Dr. Kobrin stopped receiving emails from Rami, and to this day, she doesn’t know what happened to him. Despite the extremism and clan violence, Somalian president Hassan Sheik Mohammed unofficially visited Israel in 2016.

Dr. Kobrin introduced us to a Somalian acquaintance of hers who was living in Nairobi, whom she thought could help us in our own search for Jews. Abdi Moham, a tall, distinguished Somalian living in Kenya, met me at a Nairobi coffee shop and said hello in perfect Hebrew. Abdi related how he spent ten years living in Israel and went to the IDC in Herzliya for university. He is unabashedly pro-Israel, speaks Hebrew fluently, and dreams of building bridges. As we started to stroll down the dangerous streets of Nairobi, I wasn’t too nervous, as he is the son of a chief of one of the main clans in the country.

Ari Z. and I knew that for the last 150 years, small groups of Yemenite Jews lived on the East African coast doing commerce. We once met a Jewish woman in Nairobi who showed us her father’s Somalian passport with stamps from his entry into Israel in the early 1950s — and his signature was written in the Yemenite Rashi script in Hebrew. She described how her family would get together with the few other Jewish families in the country on Yom Tov, but otherwise lived a completely isolated existence.

We have talked with descendants of the original five Jewish Yemenite families who lived in Sudan — located on the other side of Kenya — in the 1880s and found themselves in the center of a Muslim messianic movement. A certain Muslim ruler proclaimed himself the as the mahdi, the Muslim messiah, and instituted extremist rule. He forced all non-Muslims to convert to Islam and to marry a Muslim wife. One of these people told us how the family kept a secret shul in their cellar, and 18 years later, the mahdi was killed and the Jews could once again emerge. Once they were able to appear as Jews again, all their non-Jewish family members converted and became mitzvah-observant — and these families became the kernel of an active Jewish community there before the 1950s.

Abdi, for his part, told us of a fractured country controlled by militias, one more religiously extreme than the next. Today no woman in Somalia would dare walk outside without being accompanied by her male relative, and would not deign to uncover her face — and sometimes even her fingers — for fear of death. In fact, his own mother worked with a Western charitable NGO and was threatened with death if she didn’t quit. When a high-end hotel was built for traveling businessmen, it had to be built within the airport complex so that Westerners could do business in Somalia without actually entering the country and endangering their lives.

Hearing these stories of oppression and disappearance on one hand, and yet seeing for ourselves how Jewish-oriented groups are now emerging against all odds on the other, is pretty amazing, and I feel privileged to witness the transformation around the globe and be able to share a small part of it. It’s almost like being in some kind of futuristic play — and who knows what the last act will look like?

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 899)

Oops! We could not locate your form.