Meeting of Minds

Relaunch of the RJJ Journal of Halacha and Contemporary Society

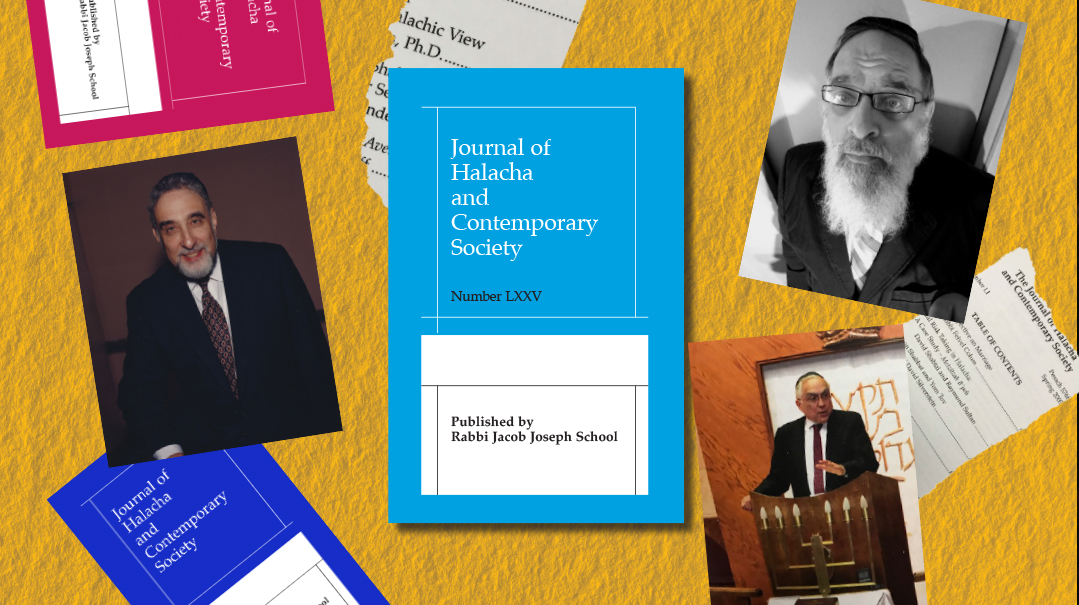

Photos: Personal archives

In the greater academic world, scholarly journals are famous for their strict demands of brevity, clarity and impersonality. They are also infamous for being pretty boring. Hence, the re-launching of an academic, scholarly journal after a two-year hiatus is hardly news that’ll “break the Internet.”

Yet the recent reintroduction of the esteemed RJJ Journal of Halacha and Contemporary Society — a scholarly publication whose issues deal in real time with halachah and its interface with modern-day issues (“Techum Shabbos at the Airport,” “Tevilas Keilim for Electric Appliances,” two examples of hundreds of practical pieces that have been published over the years) — is sure to be greeted by grateful readers who’ve missed the tackling of serious topics in a sophisticated and analytical manner, yet with a certain geshmak.

Readers for over three decades have been inspired to see how the Torah’s laws, which ostensibly deal with “goring cows” and other arcane subjects, serve as a cogent blueprint for tangible, current situations. The applied reality of halachah to real-life circumstances as the very fabric of our lives — a demonstrable, “ki heim chayeinu v’orech yameinu” — is not some incidental feature of the RJJ Journal; it is, by design, the very objective of the Journal from the get-go.

Some 35 years ago, Rabbi Alfred (Avraham) Cohen, a mesivta rebbi in MTA and rav of Congregation Oheiv Yisrael in Monsey, was talking to his friend, Dr. Marvin Schick a”h, a tireless askan in Jewish communal initiatives and especially in Jewish education, who considered his efforts a shelichus of his rebbi, Rav Aharon Kotler. Rabbi Cohen was bemoaning the fact that most American Jews lacked an appreciation of the profundity of the Torah logic and its modern-day application.

Dr. Schick, ever the man of action and president of the Rabbi Jacob Joseph yeshivah (RJJ) network (at the behest of Mr. Irving Bunim, he took the reins of the floundering mosad and restructured it to include a pair of elementary schools in Staten Island and a mesivta and beis medrash in Edison, New Jersey), offered to fund the publication of a halachic journal in English if Rabbi Cohen would edit it.

As a landsman from Monsey and one-time neighbor of Congregation Ohaiv Yisrael, I had frequently davened in Rabbi Cohen’s shul. Like the many other kollel yungeleit who began their married life in a row of apartments that abut the shul, I greatly enjoyed the Rav’s frequent halachic derashos. Clean-shaven, with a wry sense of humor, Rabbi Cohen didn’t necessarily fit into the narrow profile of the type of talmid chacham we yungeleit were used to, but we soon learned to expand our horizons. His shiurim were like the journal itself — halachically relevant, spanning a wide variety of topics, erudite, entertaining and to the point. In fact, everything about Rabbi Cohen is driven by a no-nonsense approach to unadulterated truth, including his sense of humor, which gives expression to the aphorism, “Humor is what happens when we’re told the truth quicker than we’re used to.”

Rabbi Cohen remembers how Dr. Schick, who passed away last spring, jumped onto the idea of presenting an English-language journal to demonstrate the wisdom of the Torah as it applies to real times.

“He assumed the responsibility to fund it, and he did so for some 35 years until a few years ago when I retired,” says Rabbi Cohen. “We published semi-annually, so that would come to more than 70 journals we partnered on.”

After Rabbi Cohen retired, his son Rabbi Dovid Cohen, rabbinical coordinator for the CRC in Chicago, assumed the editorship for several years, but when time constraints did not allow him to continue, the journal ceased publishing. After Dr. Schick passed away, however, his family was interested in reviving the magazine. They put together a team of editors, headed by Rabbi Benzion Sommerfeld, himself a veteran talmid of RJJ’s yeshivah gedolah in Edison and described by RJJ rosh yeshivah Rav Yosef Eichenstein as “a tremendous talmid chacham whose erudition and clarity of thought in all areas of Torah are unusually impressive.”

(Rabbi Yaakov Feit, well-known for his published halachic articles, and Rabbi Aviyam Levinson, who came on board on recommendation of Rav Aharon Lopiansky, are serving as managing editors.)

Staying Relevant

In sync with the times, the new launch focuses on issues arising from the pandemic, including a piece by YU maggid shiur Rabbi Joshua Flug about davening over Zoom, an article by Rabbi Yosef Gavriel Bechoffer about wearing masks, related coronavirus teshuvos by Rabbi Yisroel Reisman, and many other on-topic pieces.

But while each volume deals with contemporary issues, the journal never really gets old, and back-issues are often sought after when it comes to halachic research (a digital disc collection is currently available for those who don’t keep stacks of old issues in their basement, and the journal will soon be launching a website — www.rjj.edu — where all archived volumes will be accessible).

To illustrate this, permit me to share a personal story: For this magazine’s recent article about shomer Shabbos medical residencies, I had been asked to review a halachic sidebar as to whether one may participate in residency that is not Shabbos-accommodating. The sidebar presented the stringent view, which in fact is the view of most poskim, but I knew that there were rabbanim who were more lenient. Where to start? I called one rav, who led me to a second rav, who in turn suggested a certain major posek — who agreed that there is a basis for leniency, but asked not to be quoted. So now what?

Someone suggested I check the RJJ Journal. “Surely,” he surmised, “the Journal has addressed the topic.”

So I called Rabbi Cohen and, bingo! He informed me that in the Fall 2005 issue of the RJJ Journal there is indeed an article dedicated to this very topic. (He loaned me his copy.) The piece raised all the issues involved and concluded with the varying views of contemporary poskim, one of whom was that very posek who now declined to be quoted. I guess things change over 15 years.

Of the over 500 titles that have been published in the last 35 years, many are still clearly relevant to this day. “May Parents Refuse Vaccinations for Their Children?” “Cloning,” “Child Molestation in School,” and “Preconception Gender Selection” might have been written years ago, in the midst of a particular halachic tumult, but they’re still as relevant as ever.

Fair to Both Sides

One of the things both veteran and new readers appreciate is the Journal’s stated objective, not to take sides on an issue, but to show various halachic perspectives.

“Let me tell you a story,” says Rabbi Cohen. “Several years ago I wrote an article about whether the issur of chodosh [wheat planted in the summer and eaten before the time of the omer offering on Pesach] applies outside of Eretz Yisrael. Later, I met a rav who had read the piece. He told me, ‘If you’re not makpid to only eat yoshon then I won’t be either.’

“Somewhat later I met a rosh yeshivah who also read my piece and told me just the opposite. ‘If you are makpid to only eat yoshon, then I will be too.’

“I went home and told my wife, ‘See. I did a good job. I presented both sides perfectly.’ ”

But sometimes the issue is just so important that Rabbi Cohen has had to bend his own rules. Back when I was learning in a kollel in Monsey that was headed by Rabbi Chaim Zev Malinowitz ztz”l, there were two cases pertaining to Jewish marriage and divorce that caused a tremendous chillul Hashem.

In the first case, an ex-husband invented a new angle on the agunah extortion threat. Instead of withholding a get from his wife, he claimed that he had married off his young daughter to some man — a father is halachically empowered to do so in an arrangement known as kiddushei ketanah — but he refused to say who the man was… unless, of course, he received the settlement he was asking for. In other words, instead of making his wife into an agunah, he made his daughter into an agunah. The story made headlines, and also a terrible chillul Hashem.

In the second case, a bill was introduced to the New York State Senate, whose objective was to punish a recalcitrant husband who refused to give a get, by empowering a secular judge to confiscate all the husband’s money unless he gave the said get. The bill was fast-tracked and passed before the poskim could weigh in on it. While it sounded like a noble resolution to a heartbreaking problem, most poskim held that a get coerced under such circumstances would be considered a get meuseh — a “forced get”— which is invalid. This, too, caused a chillul Hashem, for after all, they said, “here we finally have a solution, and the rabbis interfere!”

Regarding both cases, Rabbi Malinowitz submitted a comprehensive article to the Journal, articulating the very real issues involved, presenting possible solutions and hashkafic perspectives. Yet in a sense, both these pieces were inconsistent with the Journal’s mission of presenting both sides of an issue.

“That’s right,” Rabbi Cohen admits, remembering the background of that piece. “But Rav Chaim Zev was a man of very strong convictions. His article was an important contribution to that entire discussion.”

Balancing Act

Indeed, the Journal always prided itself on weighing all sides and avoiding any kind of shrill or extreme position.

I will quite arbitrarily choose one article, written by Rabbi Cohen himself, entitled “Protest Demonstrations,” as an example of the dispassionate, fully halachic perspective the magazine assumes in addressing its topics.

This particular piece addresses the volatile issue of whether the hafganos — the demonstrations in Jerusalem against chillul Shabbos, desecrating cemeteries, and so forth — are halachically grounded and advisable. Now, instinctively, one may jump to the conclusion, “Oh, I know where this is going. A scholarly, academic article authored by a rebbi in MTA is most certainly going to find the hafganos by the extremists nothing short of repulsive. No chance of this being an honest and balanced discussion about the very real issues involved.” But that instinct would be wrong. The 32-page, heavily annotated article tackles the issue from every possible angle.

It begins unflinchingly, by citing a line in a book review in the New Tork Times:

There is perhaps no group of Jews held in as much disdain by their fellow Jews in both Israel and the United States as the ultra-Orthodox “Haredim.” At the same time, many have praise for their spiritual courage which never wavers in confrontation with those they believe to be secular non-believers. There is no question, however, that they arouse tremendous hostility, especially when they throw stones at Sabbath-desecrators or make other volatile objections to activities they perceive as unacceptable.

And then the Journal article proceeds:

Whether or not one finds their behavior embarrassing is not the issue. What is of utmost importance is to know whether their public protests have intrinsic value, or whether, on the contrary, they are causing more harm than any good they might achieve and could even be causing a chillul Hashem….To what extent does Jewish religious law approve public protests against the desecration of Jewish law?

The article then examines the mitzvah of tochachah (reprimanding a fellow Jew), exploring whether this mitzvah is “purely functional,” concerned only with helping the sinner mend his ways, or whether there may be other reasons for voicing protest, perhaps “so that others will not think the sinful action is acceptable, or even to impress upon the sinner that his action is wrong, even if there is no hope that he will change his ways at this time”?

The article weaves together a wide tapestry of sources, ranging from the Teshuvos HaRashba to the Zohar, the Satmar Rebbe, Techumim, Maharal, Chazon Ish, Igros Moshe and more.

It concludes thus:

Our brief survey indicates that for most rabbinic decisors, the mitzvah of tochachah is goal-oriented — its primary purpose is to effect a positive change in the behavior of an errant Jew. However, a significant number of authorities also consider it highly necessary, not only for the immediate observer but even more for the Jewish people as a whole, that the eternal truths of our Torah not be forgotten nor be trampled upon without at least some demurrer… Someone must tell the world that there are still Jews who respect and revere G-d’s word as the living constitution for our lives… Moral outrage must be expressed so that, at a minimum, our children will know that it is wrong to violate the dictates of the Torah…

In reviewing the multiple variables… we see that there is a broad spectrum of rabbinic opinion. Some counsel strong, even violent protest, while others caution that such action might engender hostility. What seems quite clear is that no one sanctions ignoring the mitzvah of tochachah. The question is rather, what is the best method to use in order to return our brethren to observance of mitzvos. But nowhere is there an excuse for failure to react to transgression. There is justification, perhaps, for strong protest (although that is the view of a very small minority) but there is an even stronger mandate for intensive and continued outreach to our fellow Jews. What is undeniable, however, is that we may not choose to do nothing, to act as if wholesale desecration of Torah values warrants no response.

This balanced conclusion surely has enough to make both sides happy and upset. But it is undeniable that the article is illuminating, and that it elevates this highly charged topic by viewing it under the bright light of halachah — and that lesson, that halachah is the prism by which all life must be viewed, is most certainly invaluable.

The Target

As evenhanded as the Journal tried to be, it hasn’t totally stayed out of controversy. And even if things sometimes got sticky, Dr. Schick, who was the sole financial supporter, trusted Rabbi Cohen’s decisions, backed him completely, and never once interfered with the content.

With such an emphasis on balance though, what kind of controversy could the Journal find itself tangled in?

“Well, without getting into details,” says Rabbi Cohen, “someone once submitted an article about the laws of a moser, an informer, who is treated very harshly in halachah. Since it’s a delicate matter, I decided to approach Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky for direction. It was the first time I met him and I had a hard time securing a meeting. Eventually the gabbaim granted me five minutes.

“I entered the room, got my answer, and was about to leave, when he told me that he wanted me to write about a highly sensitive topic that was not generally spoken about in a public forum. He kept me there another 45 minutes, during which time he described the issues involved and how he wanted the topic to be addressed. He also asked that we not disclose his name.

“We did the piece, and it did indeed generate controversy, but all I ever said was that it was done at the behest of a well-regarded rosh yeshivah. Everyone assumed that it was Rav Yoshe Ber Soloveitchik, but it wasn’t.”

With both a subject list of the day’s hottest topics and a scholarly, academic format, who, exactly, is the target audience? Talmidei chachamim? Professors? Balabatim?

“I would say, basically anyone with a decent Torah background and a somewhat intellectual bent. The readers, like the authors, of the essays, span the range of Torah Jews.” Over the years, Rabbi Cohen has received many phone calls from big-name rabbanim who were planning to say a shiur on a certain topic, and who wondered whether the Journal had ever addressed it.

I tell Rabbi Cohen of a good line I came across. Chazal say that if the Jews would observe two Shabbosim, they would be redeemed immediately. Someone quipped that it refers to Shabbos Hagadol and Shabbos Shuvah, when the rabbis deliver their major derashos. If they would only reveal their sources, they would bring the Redemption, because “Ha’omer davar b’sheim omro meivi Geulah l’olam.”

He laughs. “I never cared to get the credit. I was only too happy to share the Torah with them.”

Rabbi Cohen insists the Journal was not meant to be a kiruv tool in any way, but that’s not exactly true. I tell Rabbi Cohen that I know of at least one case where it unwittingly was. Rabbi Gil Student, publisher of TorahMusings and who is serving as a consultant for the revived RJJ Journal, told me that he grew up attending a Conservative synagogue and as a teen he would spend a lot of time in the rabbi’s home. The rabbi, who was personally Torah-observant, had an extensive library, which included the RJJ Journal and Rabbi J. D. Bleich’s books on contemporary halachic issues, from science to ethics. These works made a huge impression on him regarding the intellectual sophistication of the Torah, moving him to teshuvah and to attend YU. So, perhaps the Journal serves that purpose too.

For the Honor of Torah

When Dr. Schick’s family decided to sponsor the relaunch of the Journal, it was their way of paying tribute to a man totally devoted to the Klal, without personal negios.

“The Journal, like everything else he was involved with, was never about him, his type of Jew, or his agenda,” says his son Avi Schick, an attorney and former deputy attorney general for the State of New York. “It was about kevod Shamayim and kavod HaTorah. My father was pleased that the Journal could not be pigeonholed, that it had contributors from talmidei chachamim across the board.

“When my father saw something that he considered essential for the Torah community, he just did it. He viewed these as opportunities worth pursuing, not as obligations that were a burden.”

So perhaps it is fitting to repeat the description penned by his wife Malka in the dedication of this new issue of the Journal:

“A visionary and activist, his life’s work was guided by Rav Aharon Kotler’s last words to him. He never lost sight of the charge to devote himself to the klal. His tireless efforts on behalf of Orthodox Jewry knew no bounds and are reflected in his wide-ranging accomplishments. At the same time, he generously and empathetically helped countless individuals. In every way, he was a gift to Klal Yisrael.”

According to Avi Schick, keeping the Journal going is essentially a perpetuation of his father’s legacy. “He had a special soft spot for talmidei chachamim and assisted them in every way. He helped facilitate and make possible the publication of Rav Feivel Cohen’s Badei HaShulchan, he was a driving force in the publication of the Mishnas Rav Aharon, and he arranged for the publication of many, many other seforim.” Launching and sustaining the Journal of Halacha together with Rabbi Cohen was in that same vein. To him, this project was the greatest kavod HaTorah. Our family’s tefillah is that the Journal should carry on with that vision.”

Readers, happy for the second chance, hope so too.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 848)

Oops! We could not locate your form.