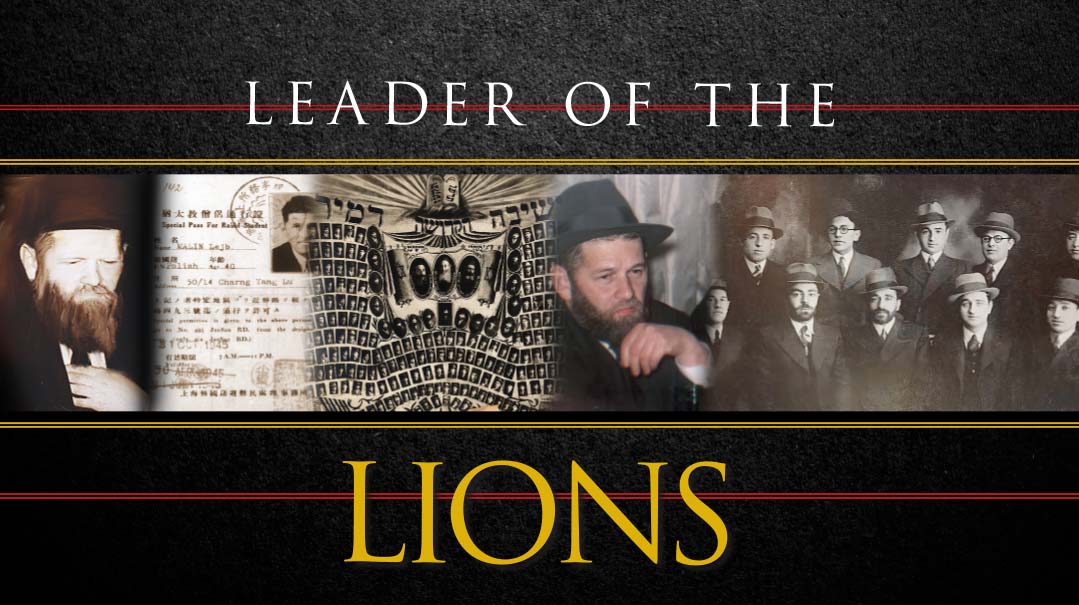

Leader of the Lions: The Story of Rav Leib Malin

| September 14, 2021Rav Leib Malin was a young talmid in prewar Mir when he heard the words that would become his mission

Photos: Moshe Yarmish, Karmel Family, Archives of the Mirrer Yeshiva, Hazericha Bepaasei Kedem, Yad Vashem, Kedem Auctions, Yated Neeman (Israel) , Kamenetsky Family, DMS Yeshiva Archives, Artech Marketing, Feivel Schneider

Part 1: Lion of the Mir

It was the summer of 1940 in Lithuania. The students of the Mir Yeshivah, who had escaped from occupied Poland, were in turmoil. The Soviet takeover of the region meant that their lifeblood — Torah learning and observance — was in imminent danger. Yet a savage war was raging. How could they risk leaving their refuge and incurring the very real possibility of a punishing Siberian exile?

Then, from amid the confusion and uncertainty, emerged a voice of clarity. A small group of talmidim — bearing no official titles but accorded respect and deference by the entire yeshivah — had determined that the yeshivah could not remain in Lithuania, subject to antireligious Soviet domination. They had to escape. And they had to escape together, as a single unit.

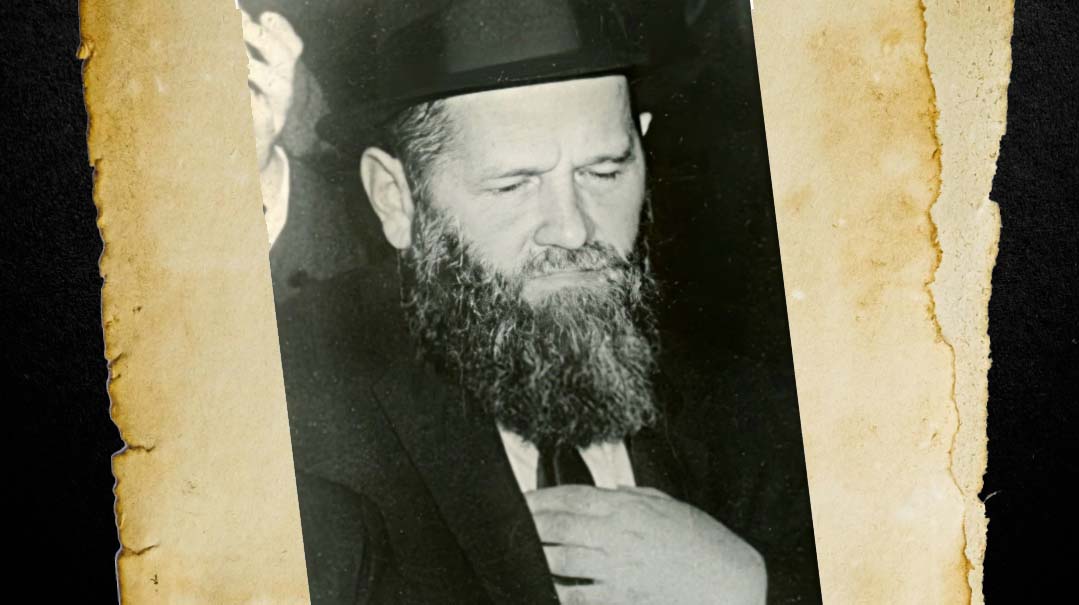

The vision, the authority, and the tenacity behind the escape plan traced back to a talmid who was the “leader of the lions.” He was unmarried and clean-shaven and held no official position. But Rav Leib Malin had long gained renown as a leader. And with the ensuing decades, he would demonstrate his capacity to build, save, preserve, and recreate the essence of the yeshivah.

“Stand By Your Decision”

Rav Aryeh Leib Malin, widely known as “Rav Leib,” was born near Bialystok in 1906 to Rav Avraham Moshe Malin, who served as the local dayan. The Malins originated in Brisk, where Rav Leib’s ancestor, Rav Isser Yehuda Malin, was one of the town’s rabbinical leaders. Young Leib Bialystoker began to gain repute as a serious Torah scholar during his formative years in Grodno’s Shaar HaTorah Yeshivah. “Just as one breathes air, we breathe Torah in Grodno,” was the mantra during the yeshivah’s interwar golden age. It was in this environment that he quickly made a name for himself, as he gravitated toward the rosh yeshivah, Rav Shimon Shkop.

While studying in Grodno, Rav Leib and his close friend Rav Dovid Lifshitz (later the Suvalker Rav and rosh yeshivah at RIETS) approached Rav Shimon Shkop to discuss a personal matter. After a lengthy and fruitful discussion, they apologized for taking precious time that he could have otherwise spent learning. Rav Shimon countered with the statement of Chazal: “ ‘Aser bishvil she’tis’asher — Tithe your earnings [aser] so that you will become wealthy [tis’asher].’ This principle isn’t limited to monetary contributions, but includes spiritual ones as well. Thus, a rosh yeshivah who spends time with his students only gains, and will ultimately see more success with his shiurim.”

Those prescient words would later shape Rav Leib’s outlook.

Rav Leib spent some time learning in Baranovich under Rav Elchonon Wasserman, but it was in the Mir Yeshivah that he found his mandate. In the Mir, young Leib Malin found his place among the other senior talmidim — the “lions of the Mir” — eventually emerging as the leader of the lions, in keeping with his name “Leib.” And it was in the Mir as well that he grew enraptured by the rebbi who would define the rest of his life and educational approach, the great mashgiach Rav Yerucham Levovitz. His esteem for Rav Yerucham was so great that Rav Leib referred to him as “the teacher and leader of the yeshivos during the prewar time period.”

Unlike most yeshivos of the era, Mir was unique in the role the mashgiach played in the internal affairs of the yeshivah, its curriculum, and the education of its students. In his modesty and greatness, Rosh Yeshivah Rav Leizer Yudel Finkel assumed financial responsibilities for the yeshivah while deferring these spiritual responsibilities to Rav Yerucham, whose charisma drew the elite of the yeshivah world to Mir.

Rav Shmuel Berenbaum arrived in the Mir after Rav Yerucham’s passing, yet the reverence for the venerated Mashgiach was still palpable. He related how Rav Leib saw Rav Yerucham as such a towering figure that he was like dust before him, “to the point where had the Mashgiach instructed him to go into a fire, he would have done so!”

In Rav Yerucham’s mussar shmuessen, Rav Leib found not just ethical and educational messages, but also a derech halimud. The incisive analysis that Rav Yerucham would apply to the words of Chazal, he explained, was a lesson in how one should plumb the depths of every word of Torah.

Rav Leib was once so bothered by something that occurred in yeshivah that he felt compelled to register a mecha’ah (protest). He gathered several other bochurim, and they rose to walk out of the beis medrash to declare their disagreement. Suddenly, they caught the eye of Rav Yerucham standing at the door of the beis medrash, arms crossed and eyes flashing fire, clearly willing them to sit back down. The group backed down and returned to their seats.

Later on, Rav Yerucham called in Rav Leib. “I didn’t agree with what you wanted to do,” he said, “but you had obviously made the cheshbon and felt it was the correct decision. So why, then, did you change your mind when you saw me? If you felt that it was right, then you should have been prepared to stand by your decision. You have to take achrayus [responsibility].”

Those words encapsulated Rav Leib’s mission for decades to come. His outsized sense of responsibility would fuel him to arrange the rescue of an entire yeshivah, and later to rebuild the quintessential beis medrash on new shores.

But Rav Leib assumed a position of achrayus even before the winds of war began to buffet Eastern Europe. The Mir Yeshivah was unique for the latitude it gave to the senior students of the yeshivah, who assumed active leadership roles in the day-to-day management of the beis medrash. Several of them, like Rav Leib, could have been roshei yeshivah in their own right, and were treated as such by bochurim and hanhalah alike.

Rav Leib and the other “lions of the Mir” — the term awarded to the senior talmidim of Rav Yerucham — would assign new arrivals to their respective chaburahs, where the maggidei shiur were those same senior talmidim. This role only increased with Rav Yerucham’s passing in the summer of 1936, after which his senior talmidim held even more authority on the internal affairs of the yeshivah.

Following Rav Yerucham’s passing, Rav Leib and Rav Yerucham’s sons led a group of talmidim and alumni in an effort to publish his words of mussar, Daas Chochmah U’Mussar. Rav Leib’s notes, among others, were used by Rav Simcha Zissel Levovitz in this publication.

Rav Leib also presided at the gathering of Rav Yerucham’s talmidim on his first yahrtzeit. This endeavor produced the first volume of maamarim published in Vilna in 1940 in the shadow of the war, and they continued publishing additional pamphlets throughout the years of their Shanghai exile.

LIFESAVING VISIT Reb Menashe Karmel and his son Abba (center) flanked by Rav Leib and Rav Chaskel Fleishaker (left)

Your Place Is Here

In the mid-1930s, Reb Menashe Karmel, a wealthy businessman and community leader in Krakow, was advised by his Rebbe, the Imrei Emes of Gur, that he ought to send his sons to learn under the tzaddik, Rav Yerucham Levovitz of Mir. The notion of sending boys from cosmopolitan Polish Galicia to the backwaters of Mir was unheard of. But the Gerrer Rebbe had spoken and Reb Menashe listened. His second son, Avraham Yitzchak, arrived in Mir as a 16-year-old in 1937 and was assigned by Rav Leizer Yudel to learn with Rav Leib Malin, who quickly became a fatherlike figure to the young impressionable boy.

In the summer of 1939, with war looming on the horizon, Reb Menashe requested that his son return home. The boy mentioned the request to Rav Leib, who responded, “Azoi vi ich farshtei doss — the way I understand it, your place is here with the yeshivah.”

After learning of Rav Leib’s view, Reb Menashe, a successful businessman and respected community leader, subjugated his own opinion to that of Rav Leib. Although his son’s safety was at stake and Rav Leib was still a bochur, Rav Menashe had met Rav Leib and been exposed to the force of his personality and the sheer power of his conviction.

In a poignant letter hinting that they might never meet again in This World, he urged his son to always “stay with Rav Leib and the yeshivah, for like a rare flower blooming in a desert, you will always remain a ben Torah no matter what befalls you and no matter where circumstances will take you.” That letter saved his son’s life and led to generations of bnei Torah.

While Rav Leib was in a sense a member of the hanhalah, even as a bochur in his thirties he adhered to every detail of the yeshivah’s schedule with the utmost seriousness. He davened in yeshivah, attended sedorim, and maintained mussar seder, all like a regular yeshivah bochur. Years later, someone asked Rav Leib how Lag B’omer was celebrated in the Mir Yeshivah in Poland.

“What do you mean?” Rav Leib responded. “We counted Sefirah.”

Letters and memoirs from Mir talmidim emphasize the kinship and brotherhood that was formed in the yeshivah. Rav Sholom Shapiro, a veteran Mir talmid, writes: “The yeshivah’s most distinguished talmidim actually sat [not at the mizrach vant but] along the western wall, on the benches at the back. The first place was occupied by the gaon Rav Yonah Karpilov… and in the parallel row [sat] the gaon Rav Aryeh Leib (Malin). Whoever had any difficulty with his learning went to them and they would resolve it clearly and lucidly.”

Prior to building Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin, Rav Meir Shapiro embarked upon a storied journey to observe some Lithuanian-style yeshivos in action. Visiting Mir, he delivered a shiur, and it wasn’t long before Rav Leib and others began to argue with the Polish Torah leader. Pandemonium reigned as the fiery exchange reverberated across the room. Finally, with the milchamta shel Torah completed, Rav Meir (who was hardly 40) smiled and quipped to those gathered around him, “When I reach your age, I’ll know as much as you [the ‘lions of the Mir’] all do!”

A new era dawned for Rav Leib when in 1929 Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer visited Poland from Yerushalayim, to participate in the dedication of the new yeshivah building in Kletzk. There he met Rav Leizer Yudel and casually remarked to him that the unique learning and teaching abilities of the Brisker Rav weren’t being properly utilized.

Hardly wasting a moment, Rav Leizer Yudel sent a group of his finest students to Brisk to hear shiurim from the Brisker Rav. Among others were Rav Leib, Reb Yonah “Minsker” Karpilov Hy”d, Rav Michel Feinstein, Rav Henoch Fishman, Rav Naftali Wasserman, and Rav Ephraim Mordechai Ginsburg. Despite the challenging economic situation caused by the onset of the Great Depression, Rav Leizer Yudel financially supported the kibbutz in Brisk.

The reverence that the younger talmidim felt for the lions of Mir was best illustrated by Rav Simcha Sheps. Initially chosen by Rav Leizer Yudel to be one of the pioneer students sent to Brisk, when he found out that Rav Yonah Minsker would also be part of that group, he turned down the privilege, explaining, “[Rav Yonah] falls into the category of ‘mori v’rabi.’ It is not kavod haTorah for a rebbi and talmid to go study by the Brisker Rav at the same time.”

The Brisker Rav became especially fond of Rav Leib, whom he treated like a son. Aided by his excellent memory and unique writing ability, Rav Leib recorded the Brisker Rav’s shiurim, which were subsequently published in stencil format. The Rav even allowed Rav Leib the privilege of borrowing his own notebooks of chiddushim, as well as those of his father, Rav Chaim. Rav Leib would memorize these novellae, return the notebooks, and be given a fresh batch to digest. The Rav also hired Rav Leib to learn with his son Rav Yoshe Ber.

Rav Leib absorbed the Rav’s approach to such a degree that he became a virtual mouthpiece for the Rav’s way of understanding. Another close student of the Rav, Rav Dovid Finkel, related that Rav Leib once sent the Rav a letter containing chiddushei Torah of his own. After reading the letter, the Rav commented, “Who wrote these chiddushim, Rav Leib or I? Rav Leib seems to have written them — he sent them to me — yet I feel that I wrote them.” Ultimately Rav Leib was buried right near the Brisker Rav, in the chelkas harabbanim on Har Hamenuchos.

THE LIONS OF THE CHABURAH: (standing r-l) Rabbis Zeidel Smiatitzky, Mordechai Krepenshprung, Michel Feinstein, Dovid Goder, Chaim Vysokier. (sitting r-l) Rabbis Yonah Karpilov, Moshe Kaplan, Gershon Kaplan, Avraham Levovitz, Leib Malin

Trembling Ground

“We merited a special and wondrous Hashgachah these seven years, since we went into exile from the walls of our home, the holy yeshivah of Mir. It would be appropriate if the entire saga of the exile of our yeshivah were recorded for posterity in a special book, to relate the chesed bestowed upon us by Hashem to the entire yeshivah and to every individual. Many times we found ourselves in dangerous situations, and we almost gave up. But every time, through overt Hashgachah and miraculous ways, we merited salvation.” —Rav Leib Malin, introduction to Hatevunah, 1947

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Nonaggression Pact signed between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in the last week of August 1939 included a secret clause about the division of Poland between the two aggressors. Shortly after the outbreak of war in September, the Soviets entered eastern Poland. The occupied area, which contained many yeshivos, faced the looming threat of a Communist takeover.

In a surprise gesture, the Soviet Union ceded the city of Vilna and its environs to independent, neutral Lithuania. At the behest of Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski, many yeshivos therefore made the trek to Vilna, where they could be safe from both the Nazis and the Soviets, all without crossing an international border.

Following Simchas Torah, the Mir Yeshivah made its way to Lithuania as well. The yeshivah settled into a learning routine in the shtetl of Keidan, but the ground beneath them was trembling. A Soviet takeover of the Baltic States seemed imminent.

Lithuania was officially incorporated into the Soviet Union in the summer of 1940, and under Communist dominion, religious life now hung in the balance. The mortal danger of the future Nazi invasion was not yet on the horizon. Instead, their immediate concern was how to sustain religious life under Communist rule. As bnei yeshivah who lived for Torah learning and observance, they tentatively began to explore the possibility of escape.

“I wish to emphasize an overlooked aspect of the miraculous escape to Shanghai. Many have spoken and written about this story without stating the facts accurately. The one who deserves the most credit for the rescue is Rav Leib Malin. The logical course, as well as the course of action advised by the great Torah leaders of the time, was to abstain from the dramatic step of requesting exit visas from the Soviet regime. It was seen as too dangerous and risky. Rav Leib saw things differently. Despite the fear of deportation to Siberia, he felt that escaping the Communist clutches superseded everything. Under a regime with a mission to eradicate Torah, Shabbos, and Yiddishkeit, one must pursue any avenue, even if it seems like just a crack in the wall.”

Thus testified Moshe Zupnik, one of the key activists in the Mir Yeshivah’s escape. He recalled Rav Leib declaring emphatically that “just as the Kohanim had to risk their lives to fight the Greeks who sought to eradicate the Torah and deny belief in G-d, the Jews had to escape the evil Communists.”

It was this fear of living under the G-dless Communists, and being required to accept Soviet citizenship, that motivated Rav Leib to ensure that the yeshivah’s hundreds of Polish citizens received passports from the Polish government in exile, which was then operating out of the British consulate in Kovno. The hope was that the passports would enable them to shake free of the Soviets.

While the Mir Yeshivah was still in Keidan, the gadol hador and patron of the yeshivah world’s refugees, Rav Chaim Ozer, heard rumblings of their efforts to escape the region. He, like most others, was opposed to the idea of hatching flimsy escape routes that were more likely to land the potential escapees in Siberia. Having no knowledge of a future Nazi invasion and the German policy of mass murder, his entire consideration was how best to deal with the Soviets.

Senior Mir talmid Rav Chaim Vysokier visited Rav Chaim Ozer when the latter was in his last weeks of his life. Rav Chaim Ozer inquired, “What are they saying in the yeshivah, what is the consensus among the ‘lions of the Mir’?”

Upon hearing that Rav Leib and his chaveirim were formulating an exit plan, Rav Chaim Ozer responded emphatically in almost metaphysical terms, “A yeshivah iz gresser vi der gadol hador!” Meaning, a consensus among the senior talmidim of the yeshivah could supersede his own reservations.

This consensus was central to Rav Leib’s thinking. He insisted, unlike most other yeshivos at this panic-stricken time, that the yeshivah remain a single unit and pursue an escape route together. He felt that the entity of the yeshivah — as a composite of many worthy parts — would merit the necessary siyata d’Shmaya to survive the risky escape.

(l-r) Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz with Mr. HarryFischel and Dr. Samuel “Shabbos” Friedman,engaging in rescue activities during the earlywar years

Rescuing the Last of the Lions

Beyond the confines of Mir Yeshivah, an escape route was already taking shape, and thousands of refugees began availing themselves of the opportunity.

Along with several others, a Dutch national studying at Telz named Nathan Gutwirth achieved an initial victory when the honorary Dutch consul Jan Zwartendijk agreed to stamp their visas to the Dutch-held island of Curaçao with the vague phrase, “No visa needed for Curaçao.”

Mizrachi leader, noted rescue activist, and Warsaw lawyer Zorach Warhaftig was able to procure those visas for Polish citizens as well. The next step was obtaining the legendary transit visas from the Japanese consul in Kovno, Chiune Sugihara. Then came the most decisive — and dangerous — diplomatic step: requesting Soviet exit visas.

With Warhaftig’s encouragement, the Mir Yeshivah joined the bandwagon. Rav Leib promptly sent representatives of the yeshivah to obtain the necessary documentation. Yaakov Ederman, Eliezer Portnoy, and Moshe Zupnik were among his operatives on the ground, with the latter actually sitting in Sugihara’s office processing the documents and assembling the lists.

Extensive funding for the operation, including the costly train tickets for the ride across the Russian tundra, came via the tireless efforts of the yeshivah’s president Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz. Having spent much of the previous decade fundraising for the yeshivah in the United States, he had obtained a US passport and made it there in early 1940, where he worked around the clock, even famously traveling on Shabbos to raise funds to assist the yeshivah’s escape. Reflecting on his motivation for these heroic hatzalah efforts, he shared a powerful insight with noted author Chaim Shapiro:

“I came across a Midrash Tanchuma relating the story of how the lion in the Ark wounded Noach for arriving late with his meal. Noach and his family, a mere handful of people, were taking care of myriad animals. Noach must have been exhausted…. How could he have been maimed for coming five minutes late? It dawned on me, however, that this was no ordinary lion. This lion was the last of a species. The very last!…. So how dare you, Reb Noach, be late?

“I suddenly realized that the Mirrer bnei Torah are no ordinary yeshivah boys. They are the last of the lions. How did I dare be worn out?”

As they prepared to leave Lithuania, Rav Leib and several other senior talmidim formalized their position at the yeshivah’s helm by forming a student committee of five to oversee the yeshivah’s rescue efforts. Rav Leib Malin, Rav Yonah Karpilov (Minsker), Rav Chaim Vysokier, Rav Michel Feinstein, and Rav Yaakov Brabrovsky initiated correspondence with Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz, updating him on the exit plans and the day-to-day affairs of the yeshivah. The very existence of a vaad of talmidim who oversaw the yeshivah administration at this point testifies to the role the “lions of the Mir” played and would continue to play in the developing narrative.

(Rav Yonah Karpilov ultimately decided against the escape and remained behind. He was brutally martyred in June 1941 in Slabodka.)

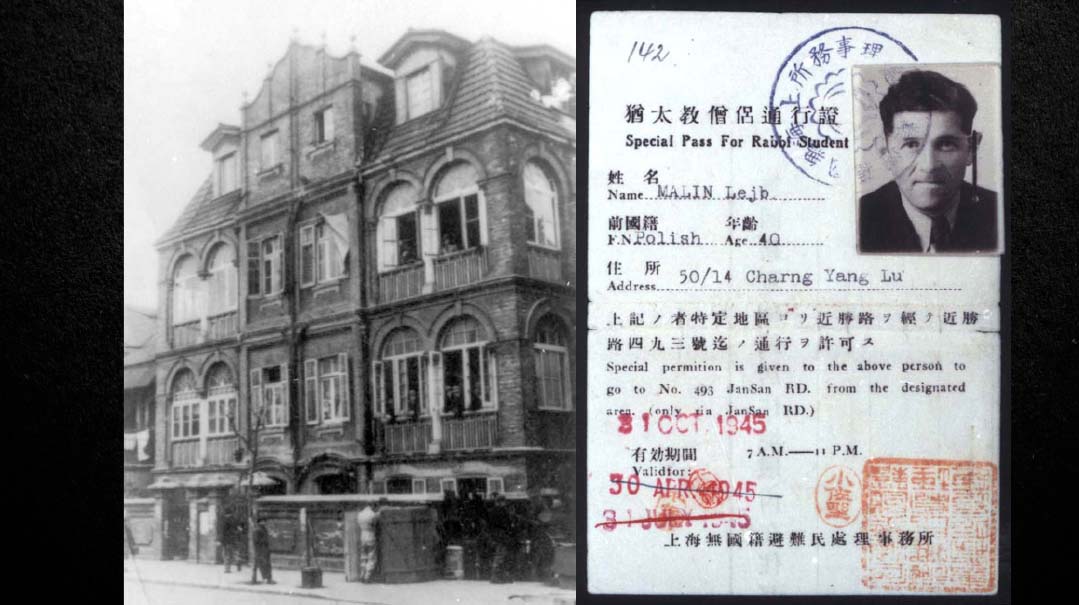

(l-r) A building used by the Mir Yeshivah in the Shanghai Ghetto; Rav Leib’s Shanghai transit pass

Part 2: Yeshivah In Exile

Leaders Don’t Leave

With the Dutch and Japanese visas having been allocated in the summer of 1940, the next hurdle of requesting Soviet exit visas was attempted that fall. Miraculously, the Soviets agreed to issue the exit visas. The impossible had been achieved. Over the winter of 1940–41,the refugees, among them the Mir Yeshivah students, made their way across the Soviet Union to Vladivostok, the gateway to the Far East. A boat ride later brought them to Kobe, Japan. At the same time, Rav Leizer Yudel headed to Palestine, where he hoped the yeshivah would soon join him.

Following their arrival in Kobe, Rav Leib wrote to Rav Kalmanowitz, pleading for his assistance as the yeshivah struggled to maintain a proper tzurah amid the nomadic conditions it was forced to endure. The yeshivah had escaped mostly intact, but they had yet to reestablish Mir in exile, and they felt that a stable yeshivah would provide an anchor of stability in a world gone mad.

To the renowned and esteemed rabbi and gaon, leader of his people

Rabbi Avraham Kalmanowitz, may Hashem guard him and protect him.

Greetings and blessings to you and yours.

I hereby express my praise to Hashem for having reached this point. I came here about a week ago…. For the most part, all the yeshivah personnel have already arrived, and together with those who are supposed to arrive tomorrow, there are a total of 178 members of the yeshivah, besides their families. The rest are still en route.

We are witnessing before our very eyes the unfolding of a chapter in the history of yeshivah life; the Torah is going into exile, and the Mir Yeshivah is going first….

[Now] regarding the current situation of our yeshivah in exile. In addition to our physical welfare, which is completely unsatisfactory — although the handful of Jewish families living here, numbering 27 families, is working tirelessly and with self-sacrifice to care for all the needs of the 1,500 refugees — nevertheless, these conditions are inadequate for the yeshivah students, who are unaccustomed to living in refugee shelters where they literally sleep on the ground and live off daily rations consisting of one and a quarter pounds of bread, and fruit that is available here in abundance.

However, this is nothing compared to our spiritual anguish at not being able to find a place where we can study on a regular basis. What are we worth and how will we live if not by studying the Holy Torah that enlivens our souls?….

On account of this issue alone, the matter of emigration to America must be arranged with utmost speed in order to save the yeshivah in its entirety….

The call of the hour is to work with utmost diligence to complete the holy mitzvah of moving the yeshivah to a place where it can reside until the “wrath has passed.”

…Perhaps we are destined from Heaven to come to America in iron chains in order to spread Torah in a place where millions of Jews reside. [Indeed,] Hashem’s plans are inscrutable.

I conclude with a blessing to his eminence that Hashem should give him the strength to uphold Torah in Israel, and he should merit to witness the true glory of Torah in Israel with the coming of Mashiach.

Best regards and much love from your friend,

Aryeh Leib Malin

In the summer of 1941, the Japanese Imperial Navy began the operational planning for the naval attack on Pearl Harbor. This necessitated the removal of all foreigners, including refugees, from the mainland in order to lessen the likelihood of an espionage infiltration. While some Jewish refugees, including some members of the Mir group, had visas that enabled their entry into the United States, thousands of others, along with the majority of the Mir students, were unceremoniously dumped in Japanese-occupied Shanghai, China.

In a letter dated Aseres Yemei Teshuvah 1941, Rav Leib wrote a lengthy and detailed update on the yeshivah’s settling in Shanghai to Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz. This historic letter includes an overview of their arrival in Shanghai, a description of the physical hardships endured by the 200 members of the yeshivah, who suffered from weakness after two years of exile, and the lack of basic living facilities, including the fact that they slept on the floor. Many of the talmidim still faced visa challenges, as much of the bureaucratic paperwork remained to be resolved.

The letter also contains a revelation: Rav Leib and 21 others obtained entry visas to the US but opted not to use them! This, he explains, was for two reasons. The ship was scheduled to sail on Erev Yom Kippur, and the question of the location of the international date line would necessitate them fasting two days straight. This would be unfeasible to impose on such a large group.

Shortly prior to departing Kobe, the yeshivah had received a message from the Rosh Yeshivah Rav Leizer Yudel Finkel in Palestine, conveying the famous dateline psak of the Chazon Ish that Shabbos is to be observed in Kobe on Sunday. As it turned out, two young cousins that were under Rav Leib’s care — Nechemia and Meir Malin — had received instructions from their father Rav Isser Yehuda Malin (not to be confused with Rav Leib’s ancestor with the same name) regarding the date line as well. Claiming to have received a tradition from Rav Chaim Brisker, his psak concurred with that of the Chazon Ish. Rav Leib was thus at the crux of the famous date line question that was relevant to their stay in Kobe.

And then comes the crucial paragraph. It is a window into Rav Leib’s worldview and outlook on the whole rescue of the yeshivah, and what it meant to him that the Mir Yeshivah was rescued as an entity.

“The primary reason [that we will not be traveling to the US at this time] is because for all of us who received the visas, our souls are bound with the souls of all the bnei hayeshivah. Our goals and aspirations are to be constantly in the company of our yeshivah in its entirety…. It is difficult for us to separate from the rest of the holy yeshivah. It is therefore inconceivable for a significant group to depart on Erev Yom Kippur, a time when everyone should be gathering together to bask in the presence of the yeshivah on this holiest day of the year. It would be detrimental for the talmidim who were left behind, as well as against our nature, which is accustomed to being part of the yeshivah at all times, and especially on such an auspicious day.

It is for this reason that we have decided to eschew the use of our visas at this juncture and we hope that there will be a future opportunity…. It is very important to us to travel together. In this way, we will be a joint foundation for the future edifice, and we will strengthen each other in Torah and yirah through our shared efforts. Whereas if we were to disperse, then perhaps some individuals won’t be able to hold their own without the group….”

In retrospect, this decision seems astounding. This sacrifice cost Rav Leib five years in Shanghai! Yet from his perspective as a responsible leader of the group, it was the only choice. The leader of the lions must stay at the head of his chaburah.

Rav Leib (far right) with Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz, rosh yeshivah of Kamenitz.

Rice, Rice, and Torah

Eighty years ago, in August 1941, the city of Shanghai became a wartime home for the Mir Yeshivah for a period of five years. While the travails of the group paled in comparison to their European brethren, it was only due to the leadership and fortitude of the hanhalah that they were able to persevere amid the lawlessness, hunger, disease, and even persecution that persisted.

Multiple stories and recollections detail the devotion of Rav Chatzkel Levenstein and Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz during those years, while the assistance the yeshivah received from the local community, led by Chief Rabbi Meir Ashkenazi, helped sustain them through the many challenges they faced in their temporary home.

During most of those years, a blanket of silence shrouded the extent of the destruction taking place in Europe. But word reached Shanghai in 1942 of the horrors in the Warsaw Ghetto, and soon rumors of the Nazis’ systematic extermination machine began to spread. Rebbetzin Ettel Partzovitz later recounted the constant and collective efforts by the older bochurim, such as Rav Shmuel Charkover, to strengthen the resolve of those who were distraught and concerned about their families’ fates.

“You have to remember the pasuk ‘Lulei Torascha shaashu’ai, az avadeti b’anyi,’ ” she said. “That was felt very strongly in Shanghai…. We all lived by this pasuk. We had nothing else.”

In hindsight, the mashgiach Rav Chatzkel Levenstein declared that the Shanghai years were five years of exceptional spiritual success. “The yeshivah was a greenhouse,” he said, “isolated from the mayhem taking place outside.”

But for those experiencing it in real time, the Shanghai period came with significant hardship.

Young Shmuel Berenbaum roomed for a time with Rav Leib in Shanghai, and was in constant awe of the way he stayed true to his values, carrying himself in the same demeanor as in Mir, Poland. Another Shanghai Mirrer related that while the debilitating Shanghai heat and humidity — temperatures could regularly exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit — had most of the students forgo wearing their jackets in the street, Rav Leib insisted on wearing his jacket at all times, his only concession being to have it slung over his shoulders. The Shanghai diet consisted of (in the words of one talmid) rice, rice, and more rice, but Rav Leib seemingly had the “protein” needed to keep up energetic, 14-hour days in the stifling beis medrash. He had the Torah.

Talmidim of Rav Nachum Partzovitz maintain that his unique method of arriving at a profound understanding of a text by reading it with precision and scrutinizing it for every nuance was the fruit of the hours that he spent studying with Rav Leib in Shanghai.

When Reb Simcha Nadborny was asked if he had ever gone over to “talk in learning” with Rav Leib during the five years they spent together in the same beis medrash in Shanghai, his immediate reply was, “Me? I was young. Younger talmidim were nervous to speak to Rav Leib! We were in awe of him. The only one our age who spoke to him regularly was Rav Nachum Partzovitz.”

Part 3: Building Beis Hatalmud

What a Yeshivah Should Be

In the late ’40s, the Torah world began its stirrings of rebuilding. Yeshivos were founded and expanded, and the hundreds of Mir talmidim who had formed a cohesive unit in Shanghai began to disperse. Many married, began families, and found jobs. Others procured Torah teaching positions in various yeshivos. A smattering immigrated to Eretz Yisrael. A large group of the younger students remained with their patron Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz, who established the Mirrer Yeshivah in Brooklyn.

Yet two giants of prewar Mir — Rav Leib Malin and Rav Chaim Vysokier — felt that none of the available options fully actualized the essence of the European prewar yeshivah. They sought to generate an atmosphere reminiscent of Kelm’s Talmud Torah and the Mir of Rav Yerucham Levovitz. They visualized something else, something different, a continuation of everything they’d fought so valiantly to preserve. Armed with little — neither money nor major supporters — Rav Leib had a directive from his rebbi Rav Yerucham, and he intended to honor it.

Shortly before Rav Yerucham’s passing, he had addressed a chaburah of Mir alumni in Lodz. Rav Leib saw those words as Rav Yerucham’s last will and testament.

“Who more than you is familiar with what the tzuras hayeshivah is to be? To dwell in the depths of study…. You are all students of our holy yeshivah and I see that aside from the vast amounts of Torah you’ve received from the yeshivah, which is an external accomplishment, you’ve come to understand and internalize the essence and the spirit of what the holy yeshivah is…. You can have an impact on those who never gazed upon the walls of the yeshivah. Through their connection to you, they will also be considered talmidim of the holy yeshivah. Through this merit, you will always be considered talmidim of the holy yeshivah for eternity.”

The primacy Rav Yerucham accorded to the tzuras hayeshivah, and his charge to his students to share it with others, burned fiercely in Rav Leib. After his arrival in New York in 1946, he initiated a publication called Hatevunah to disseminate Torah and mussar. It was credited only to “talmidei yeshivas Mir,” but the publisher as well as the anonymous author of its legendary introduction was Rav Leib himself. The Brisker Rav, upon reading the introduction to Hatevunah said “no one has written about Torah this way since Rav Chaim Volozhiner.”

Aside from citing the above passage from his rebbi Rav Yerucham, Rav Leib laid out his vision of the role that yeshivos have played in building and preserving the spiritual infrastructure of the Jewish People. It is a profound document, a prophetic clarion call of what a yeshivah is and should be. Emphasis was placed on the “tzuras hayeshivah” — the essential form of the yeshivah — which would become a term synonymous with the name of Rav Leib Malin himself. And in those few pages, he spells out his vision, which would germinate into one of the greatest and most unique phenomena in the annals of the yeshivah movement — the founding of Beis HaTalmud.

It is a sign of Hashgachah from Above, that in our weak and lowly generation… we merited a great light in the form of Rav Chaim Brisker of blessed memory, who arrived like an angel to reveal to us the depth of Torah understanding….

And even more so in Toras hamussar, which was abandoned entirely, lying completely neglected by the wayside. Hashem sent an angel in the form of the ‘Light of Israel,’ Rav Yisrael Salanter. He opened the gates of mussar, and taught us how to approach its ways…. The yeshivos adopted Toras hamussar, and an entire universe of Torah and yirah was established as a result….

[Rav Yerucham] would safeguard the tzuras hayeshivah as if it were his most valued possession, so that it would never chas v’shalom change in any way from the tradition that we have received from our ancestors…. When inside the yeshivah, one was cognizant of the kingdom of Hashem…. When one entered the yeshivah’s walls, one felt that the entire atmosphere was suffused with Torah…. Therein the Shechinah resided….”

This ideal, the tzuras hayeshivah, became the foundation of Rav Leib’s American venture: the spiritual edifice known as Beis HaTalmud.

The setting was to be Brooklyn’s East New York neighborhood. The time: a month after Rav Leib’s 1948 marriage to Yaffa Kreiser, the daughter of Rav Dovid Dov Kreiser, av beis din of Greiver and a maggid shiur in Kletzk. The name would be “Beis HaTalmud,” and it began with a meeting in his home to establish the initial chaburah.

Originally conceived as a kollel for an elite group of about a dozen “elter Mirrers,” Beis HaTalmud’s founding members included Rav Chaim Vysokier, Rav Shmuel Charkover, Rav Leizer Horodzeisky, Rav Levi Krupenia, Rav Leibel Shachar, Rav Simcha Zissel Levovitz, Rav Betzalel Tannenbaum, Rav Binyomin Paler, Rav Avrohom Levovitz, Rav Sholom Menashe Gottlieb, Rav Yisroel Perkowski, and Rav Binyomin Zeilberger. Hosted by good-hearted Jews in East New York, they resided in “stanzias” — family-style dormitory conditions — similar to the arrangements back in Mir.

These men were Torah princes who carried memories of the dreadful war years with them. They had lost their families and all they held dear. It took strength and determination to bear the burden of their pain. They found that strength in their firm bonds as a group — nay, a family — and together pursued Torah and mussar.

A quintessential Beis HaTalmud anecdote can perhaps capture the distilled essence of Rav Leib Malin, Beis HaTalmud, and tzuras hayeshivah. “I was there when this happened,” we’re told by a veteran student of the yeshivah. “It was Yom Kippur afternoon and we were in the middle of Minchah. As it is desirable to commence Ne’ilah before sunset, a conflict was brewing regarding priorities.”

The Beis HaTalmud custom, with its antecedent in Kelm, was to partake of a short but powerful mussar seder prior to the onset of Ne’ilah. With time running out and the chazzan about to begin the Minchah Avinu Malkeinu, Rav Leib interrupted with a decisive bang on his shtender.

“Tzvei-minut mussar seder!” he announced. Avinu Malkeinu was skipped to make way for the hallowed tradition of pre-Ne’ilah mussar.

“That was the most intense and meaningful mussar seder I ever experienced,” the Beis HaTalmud veteran finishes his tale. “Rav Leib’s unbudging sense of priorities, and his willingness to shoulder the responsibility of maintaining his vision of what a pure yeshivah should be, defined Beis HaTalmud in all of its glory.”

(Right to left) (r-l) Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky, Rav Chaim Vysokier and Rav Avraham Mordechai Herschberg, chief rabbi of Mexico; Rav Leib (standing center) participating in the wedding of his talmid Rav Mordechai Elefant; Rav Leib shlugging kaparos;

Total Immersion

The seder hayom in Beis HaTalmud began with first seder, which lasted until 1:30 and was followed by a 30-minute mussar seder. Mussar shmuessen were initially a rarity because, as a close talmid put it, “Every second of Rav Leib’s life was a shtik mussar.”

In the afternoon, they studied Seder Kodshim. A longtime chavrusa shared how Rav Leib would cite an occasional shtickel from Rav Shimon or the Brisker Rav, but “he had so much of his own Torah that all of that became batel b’shishim, insignificant in comparison.”

In the early years, when the beis medrash was filled exclusively with elter Mirrers, chaburahs were delivered by rotation, three times a week in the afternoons, and once a week in the mornings. It was a chaburah on the blatt, and the sessions got quite animated.

In the 1950s the first American-born talmidim joined the yeshivah, soon followed by a group from Chaim Berlin. In the late 1950s, fellow Mirrer Rav Yosef Liss moved to Israel, leaving his small yeshivah in Williamsburg behind, and Rav Leib opened a younger division of Beis HaTalmud to accommodate his students. It was around this time that Rav Leib purchased a three-story house on 351 Bradford Street, with the downstairs serving as the kitchen, the middle floor the beis medrash, and the upstairs as a dormitory.

In those early years, there were fewer than a dozen American-born talmidim. Beis HaTalmud remained small, unchanging, and elite. But with the arrival of the younger students, Rav Leib instituted a formal system of shiurim. Rav Levi Krupenia, Rav Binyomin Zeilberger, Rav Nosson Kamenetsky, and Rav Gershon Weisenfeld were among the early maggidei shiur. Rav Leib delivered a shiur on Shabbos. He used the shiur as a way to entice the students to remain in yeshivah for Shabbos.

“If you stay in the yeshivah for Shabbos,” he promised them, “then we’ll open a Shabbosdigge yeshivah, and I will deliver a shiur.”

Rav Leib had Rav Chaim Vysokier commence delivering shmuessen after Seudah Shlishis — but after meant after in Beis HaTalmud. One can’t eat and listen to mussar at the same time! Rav Leib himself would deliver a shmuess on special occasions as well.

Rav Nachman Levovitz shlita, a rosh yeshivah in Mir Yerushalayim, provided an insight into the uniqueness of Beis HaTalmud in its heyday, with a comparison to the great Talmud Torah in Kelm itself. Kelm as an institution and mussar philosophy was so unique that it would be impossible to reproduce its atmosphere — it can perhaps be mimicked, but mimicry will never replicate Kelm itself. Nuch machen Kelm iz nisht Kelm!

The same was true for that unique phenomenon of Beis HaTalmud. The personalities who stood at its head, with their extraordinary life circumstances, were unique to that time period, and it would therefore be difficult to replicate the powerful experience of studying there at that time. They were completely devoted to an ideal, with absolutely no distraction, and that was the legacy they transmitted to their students.

Rav Leib often challenged his talmidim, “You think that you learn in the beis medrash, sleep in the dormitory, and eat in the dining room? No! You learn in the beis medrash, eat in the beis medrash, and sleep in the beis medrash! The dormitory is a beis medrash for sleeping, and the dining room is a beis medrash for eating.”

When some talmidim grew lax in their Shacharis attendance, Rav Leib didn’t deliver a shmuess about tefillah. He said one sentence: “If the bochurim don’t come to davening, then we will have to close the yeshivah, for this is not the tzurah of a yeshivah.”

And as one of the talmidim recalls, “Nothing more needed to be said. Of course we all attended Shacharis after that, because we knew Rav Leib and understood the sincerity of his words.”

One day Rav Leib arrived to deliver his shiur, glanced across the room, sat silently for a few moments and walked out. When questioned why he hadn’t delivered shiur that day, his answer was succinct: “I perceived that the talmidim were simply not thirsty enough for my Torah.”

Once a talmid complained to Rav Leib.

“My chavrusa is less than satisfactory,” he said, “and so is the food.”

Rav Leib responded, “If your chavrusa and food go in the same sentence, then you’re not in the yeshivah atmosphere yet.”

He used the refrain “nisht arein,” not fully immersed — which was a favorite phrase of his to connote someone who hadn’t absorbed the yeshivah value system.

Rav Michel Shurkin, currently a maggid shiur in Yeshivah Toras Moshe, still remembers his days in Beis HaTalmud vividly. He recalled that once a prominent rabbi did something inappropriate and the street was abuzz with everyone discussing the story. Bothered, he asked Rav Leib how it was possible for a talmid chacham to do something wrong like that.

Rav Leib answered, “The Torah is not an oven where you bake a cake and it comes out perfect. One also needs mussar, tikkun hamiddos, and milchemes hayetzer.”

Reb Chaim Stein of Brooklyn related how he once invited some of his chaveirim from Mesivta Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin to observe the davening in Beis HaTalmud. “We were just bar mitzvah, and we observed Rav Leib Malin davening a regular weekday Shemoneh Esreh. He looked like he was davening Ne’ilah.”

Many elter Mirrers and even outsiders such as Rav Avraham Pam came for Yamim Noraim to “chap a bissele Mir.”

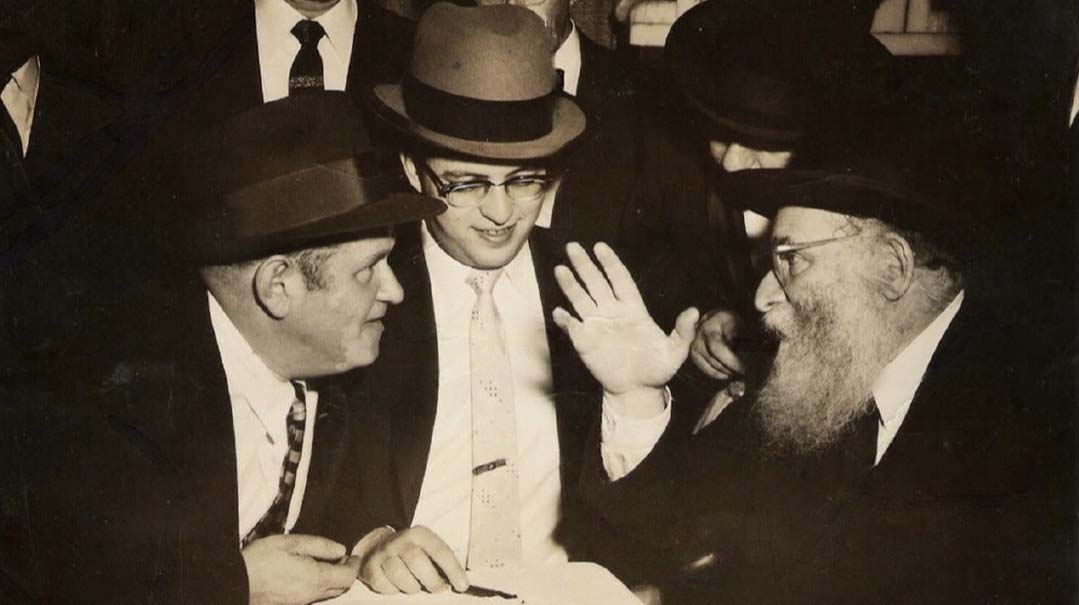

TIMES OF JOY Rav Leib conversing with Rav Aharon Kotler as Rav Nosson Kamenetsky signs the kesubah at the wedding of Rav Leib’s nephew Rav Shabsai Rubel

A Beis HaTalmud Tea

Rav Leib’s presence was so powerful that one instinctively acted differently in his proximity.

Rav Chaim Ozer Gorelick recalled a Rosh Hashanah seudah as a guest at Rav Leib’s home. Almost no words were exchanged at the table. The eimas hadin, the fear of Judgment Day, was palpable. The Rebbetzin served the food and Rav Leib recited Mishnayos Rosh Hashanah. It was an exceedingly hot day and most Brooklyn apartments didn’t have air-conditioning in the 1950s.

“I was dying of thirst and there was soda on the table,” he remembers. “Yet I couldn’t bring myself to pour myself a cup of soda. It was Rosh Hashanah, and how could one think of soda? That’s how one felt in Rav Leib’s presence. Materialism simply didn’t exist. Simple and authentic yirah was the complete reality around his table.”

Rav Leizer Horodzeisky was a member of the original Mirrer chaburah and instilled in the talmidim the message and vision of Rav Leib. In a story that has become legendary in yeshivah circles, Rav Shurkin recalls, “One hot summer day, a water cooler was installed outside the beis medrash. Rav Leizer noticed and promptly dismantled it. ‘This is not a park,’ he said.”

Like the other members of the chaburah, Rav Leizer had no airs to him. He didn’t don a frock, was clean-shaven, and sadly never married. He would often clean up the beis medrash at night while talking to the bochurim in learning. A bochur arrived from Eretz Yisrael and mistook Rav Leizer for the janitor. He wrote home with amazement, “Here in Beis HaTalmud, even the janitor is a talmid chacham!”

While the financial situation at Beis HaTalmud was never robust, Rav Leib managed to keep the yeshivah afloat. With the help of devoted balabatim like Reb Shabse Frankel, Moshe Swerdloff, and the yeshivah’s president, Mr. Louis Clark, meals were served daily and there was a dormitory for younger students. The simplicity they lived with was by design.

Rav Chaim Benoliel, rosh yeshivah of Yeshivat Mikdash Melech, related that on one of his first days in yeshivah, his chavrusa Rav Yisroel Perkowski offered him tea.

“What was tea in Beis HaTalmud?” he asked with a chuckle. “It was a cup of hot water. So what if it didn’t have a tea bag, was it nisht kein tea, therefore not considered tea?”

At one point the yeshivah had occasion to celebrate the wedding of one of its prized students. As the yeshivah headed to the wedding hall, Rav Leib approached a new talmid (now a world-renowned rosh yeshivah), and told him that as a recent arrival, he was not a close friend of the chassan and therefore had no reason to miss seder for the wedding. This bochur studied alone in the yeshivah and learned a powerful lesson in the process. Beis HaTalmud was different.

Rav Michel Shurkin once asked Rav Leib which masechta they would be studying the coming zeman.

“Maseches Menachos,” came the reply.

Rav Michel mentioned that another yeshivah would be studying Menachos.

Rav Leib looked at him with his piercing eyes and said, “S’iz an anderer Menachos [It’s a different Menachos].”

Immersion in the Gemara with zero distractions — the immersion one could achieve in Beis HaTalmud — would yield a totally different maseches.

No Compromises

When Beis HaTalmud opened its mechinah for younger students, Rav Leib reluctantly allowed for minimal general studies, in order to comply with New York state regulations. These classes were held in a separate building and taught by religious teachers who were yerei Shamayim.

Yet when a general studies teacher asked Rav Leib if he could take the students on a field trip to an aquarium on Coney Island, Rav Leib didn’t allow it. The teacher reminded Rav Leib that this was wintertime, so there would be no issue with the boys seeing inappropriately attired visitors. Rav Leib continued to shake his head.

“We don’t have to teach the students how to get to Coney Island,” he said.

Rav Leib would regularly examine the progress of the young talmidim of the mechinah. One of those he tested was his devotee Moshe Swerdloff’s young son Elya Chaim (current rosh yeshivah in Paterson). As young Elya Chaim read the Gemara, a wide smile spread across Rav Leib’s face, his sense of pride palpable.

“Morris (as he referred to Moshe Swerdloff) hut a gutte yingele [Morris has a gifted son],” he later told his chavrusa.

Once Rav Leib had the occasion to request that Moshe Swerdloff take care of some yeshivah business.

“Of course,” Moshe said. “Right now I’m busy with work, but I’ll take care of it on the weekend.”

Rav Leib corrected him, saying, “Dein (your) job is the yeshivah. Your work is to support your family.”

Priorities are important. Swerdloff ensured that the yeshivah affairs were settled that very day.

Rav Leib imparted some of his sense of achrayus for the yeshivah to its senior talmidim, instituting that members of the kollel fundraise from time to time. They were assigned cities across the country; Rav Nosson Kamenetsky covered Baltimore and Rochester, Rav Chaim Benoliel traveled to St. Louis, while Rav Mordechai Elefant would visit Kansas City and Denver. These were hardly known as lucrative stops on the fundraising circuit in those days, but they saw success and ultimately made good use of this newfound skill when they each opened successful yeshivos of their own.

Rebbetzin Yaffa Malin shared the story of a woman who would send $10 to the yeshivah on an annual basis, in honor of a family yahrtzeit. One year she sent a larger sum ($50 or $100) and Rebbetzin Malin got excited — a (rare) larger donation!

Rav Leib was more skeptical. “We can’t use it until we find out what the story is,” he cautioned. “Perhaps it was a mistake, or she sent it without her husband’s permission. With such money we can’t build Torah!”

When the yeshivah’s benefactor Mr. Louis Clark passed away, Rav Leib attended the shivah. Out of gratitude for his support, he ensured that Mr. Clark’s children observed the laws of mourning, and that they recited Kaddish in his memory. He sent students from Beis HaTalmud out to Long Island throughout the shivah to complete a minyan for them.

Nowhere was the fact that Beis HaTalmud was little more than a “Mir chaburah” more evident than at simchahs, or unfortunately at tragedies. Rav Leib was a master at sharing in the joy of the other members of the group, and also commiserating in their pain. Watching Rav Leib’s joy at a bris, one would never guess that he and his wife never merited children. When Rav Shmuel Charkover grew ill, Rav Leib barely left the bedside of his dear friend. And when Rav Shmuel passed away, Rav Leib’s suffering was so intense that it pained all of those around him to watch.

Loss of a Leader

As the East New York neighborhood began to deteriorate in the 1950s, Beis HaTalmud found itself the lone remaining Orthodox institution.

During those last few years before the yeshivah moved to Bensonhurst, the bochurim were given the keys to a shuttered shul, and some would study mussar there on occasion. One talmid shares his vivid memories of a young Rav Shimshon Pincus delivering a fiery drashah from the bimah of the empty room.

One day in 1961, while Rav Leib was walking home from yeshivah to his home on Pennsylvania Avenue, he was assaulted and injured by a local vagrant. He began to bleed from his mouth and experienced tremendous pain. The following day, accompanied by a close talmid, he visited a specialist in Manhattan who told Rav Leib that he was lucky to be alive.

“The trauma almost touched your brain,” he told him.

On Thursday night, January 4, 1962, a few weeks following Rav Leib’s injury, a fundraising meeting was arranged in the Ohab Zedek Synagogue on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where Rabbi Theodore Adams, a tomech Torah and cousin of Rebbetzin Yaffa Malin, served as rabbi. He admired Rav Leib and tried to assist whenever he could. In attendance were Reb Shabse Frankel and Rav Chaim Vysokier as well. Rav Chaim arrived late as he was in the office assisting with the preparations for the yeshivah’s annual dinner, scheduled for the coming Motzaei Shabbos.

Suddenly, in the middle of the discussion, Rav Leib collapsed due to what was assumed to be a heart attack and returned his soul to his Creator.

His sudden passing elicited an expression of mourning that the American Torah world had perhaps never seen before. Rav Aharon Kotler was so distraught that he became ill and bedridden. After he recuperated a bit, he accompanied the coffin to Eretz Yisrael for the burial, where he was maspid Rav Leib. Rav Aharon painfully mourned the man he saw as the ultimate “doer.”

“Iz avek der groise baal achrayus! The man who felt the greatest sense of responsibility has departed!” He then revealed what many in Lakewood had heard from their rebbi many times: “I believed that he would be there to take achrayus for the American Torah community.”

As Klal Yisrael’s preeminent baal achrayus, Rav Aharon wasn’t just mourning one of the greatest geonim in the postwar United States. He was grieving for American Jewry and their loss of a true leader, one who he believed possessed a true sense of responsibility. He elaborated on what Rav Leib had accomplished by citing the pasuk, “ ‘Yehudah, atah yoducha acheicha — Yehudah, your brothers will praise you.’ Yehudah grew up as one of the shevatim, and then rose to royalty through his leadership and initiative. Rav Leib was one of the bnei hachaburah. And yet he rose above the rest of the chaburah, and became someone extraordinary.”

Rav Leib’s colleague from his Grodno days, Rav Yisroel Gustman, delivered a hesped as well. “The Menorah in the Beis Hamikdash had all kinds of decorative ornaments. In contrast, the Aron Kodesh lacked any external decorations. Veil di Aron iz gevein Torah! For the Aron represents Torah itself, and the Torah needs no decorations. The Torah shines with its essence. Rav Leib didn’t need any externalities, for he personified the Torah itself!”

Rav Leib’s written legacy was published posthumously by his nephew Rav Berel Povarsky, under the title Chiddushei Rav Aryeh Leib. It has become a classic Torah source in yeshivos worldwide. More recently, Rav Leib’s close talmid Rav Chaim Ozer Gorelick has published the popular Chiddishei U’biurei Rav Aryeh Leib.

Though he was taken from This World at the age of 56, Rav Leib Malin’s legacy and impact reverberate within the hallowed halls of yeshivos around the globe nearly six decades after his untimely passing. For Rav Leib’s influence wasn’t limited to his own Beis HaTalmud, or the students of prewar Mir, or the chaburah of the Brisker Rav, or the exiled yeshivah in Shanghai. Rav Leib accepted the charge to construct the tzuras hayeshivah itself, and those borders are the walls of the beis medrash wherever they may be. —

Note: The comprehensive works and knowledge of the following esteemed individuals and publications were utilized in the preparation of this article: Rebbetzin Yaffa (Malin) Ebner a”h, Rav Shimshon Pincus ztz”l, Rav Mordechai Elefant ztz”l, Rav Aharon Kreiser ztz”l, Rav Michel Shurkin, Rav Chaim Benoliel, Rav Chaim Ozer Gorelick, Rav Nachman Levovitz, Rabbi Yosef Kamenetsky, Rabbi Yosef Karmel, Rabbi Aaron Zuckerman, Rabbi Moshe Kolodny, Rabbi A. Hakohen, Rabbi Avraham Birnbaum, Rabbi Shimon Meller, Rabbi Binyomin Karman, Rabbi Dov Eliach, Rabbi Yaacov Sasson, Rabbi Gavriel Schuster, Reb Chaim Shapiro z”l, Dr. David Kranzler z”l, Yisroel Besser, Moshe Benoliel, Yehuda Zirkind, and the authors of Hazerichah B’paasei Kedem.

In her own words

Rebbetzin Yaffa Malin’s tribute to her husband, penned for Rav Leib’s 42nd Yahrtzeit

In 5707 (1947), we were living in Tel Aviv. My brother-in-law, the gaon HaRav Dovid Povarsky ztz”l, rosh yeshivas Ponevezh, and his family also lived with us after having managed to escape from Lithuania in 5701 (1941).

After my father, the gaon and tzaddik HaRav Dovid Dov HaLevi Kreiser ztz”l, was niftar in 5691 (1931), my brother-in-law filled his position as a father figure. As was his wont, Reb Dovid was not a man of many words, and he sometimes surprised me with the steps that he took. I did not fully understand his reasoning or grasp his plans beforehand. Over the years, I became used to this conduct.

[One day] in Av 5707, upon returning home from my work as a Bais Yaakov teacher, Reb Dovid handed me a sefer — Hatevunah, part one — which had just been published, and, without any further explanation, asked me to read the introduction. I read it once, and then read it again to understand it better. I looked for the author’s name and couldn’t find it. My first question to my brother-in-law was, who had written it?

Without any ado, he told me that it had been written by Reb Leib Malin, and then he added, “And you are going to America…” I learned a little from Hatevunah about the man that I was going to meet.

In the meantime, Av came to an end and Elul arrived. One Friday, two weeks before Rosh Hashanah, when I returned from work, my brother-in-law, Reb Dovid, informed me that I would be setting out on Sunday by boat for the United States. Without any earlier preparation, I had to ready myself for a hasty departure. It should be borne in mind that the situation in Eretz Yisrael was extremely tense at that time. Tel Aviv was subject to a nighttime curfew, during which it was dangerous to leave one’s house. I had to prepare for a journey and it was almost Shabbos! I had hoped to spend the Yamim Tovim with my family but Hashgachah planned otherwise.

I set sail as planned on Sunday morning for the United States aboard a US Navy vessel that had served in the Second World War.

On the second day of Rosh Hashanah, we arrived in New York, and after Yom Tov was over, I disembarked.

On Asarah B’Teves 5708 (1948) we became engaged and in Adar II we were married.

A short time later, a meeting was held in our home, and that day, Beis HaTalmud was established.

I heard it said that when Reb Leib arrived in America, the gaon HaRav Avraham Kalmanowitz proposed that he join Yeshivas Mir as a rosh yeshivah and that HaRav Moshe Feinstein had also offered him a position as a rosh yeshivah in his yeshivah, Tiferes Yerushalayim, but that Reb Leib, feeling a broader responsibility, had turned these offers down. He had other thoughts and other plans.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 878)

Oops! We could not locate your form.