Keep It Real

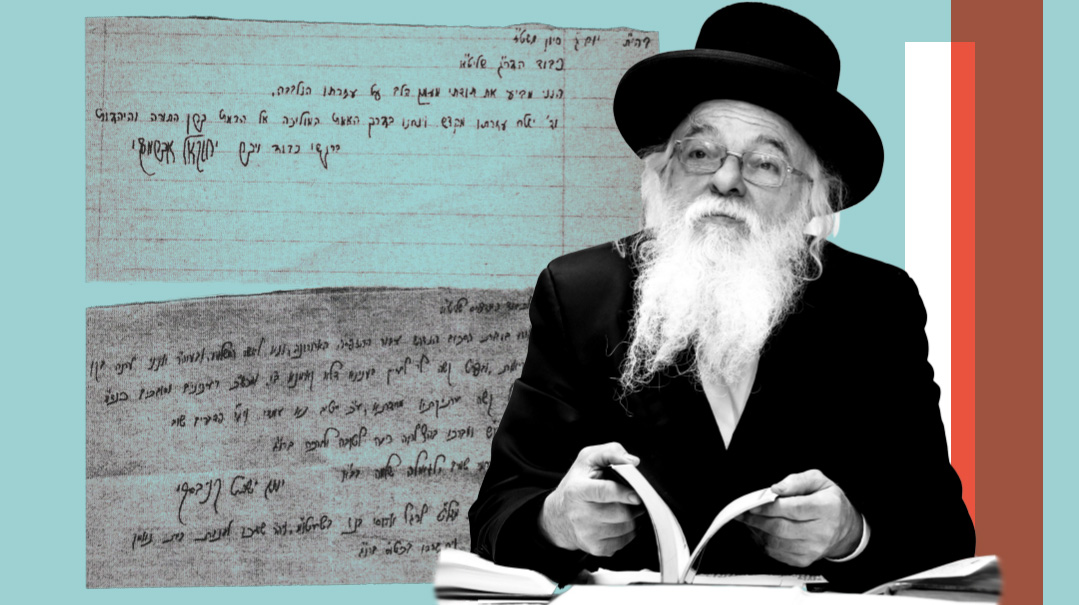

Forgery expert Rav Yitzchak Yeshaya Weiss exposes tricksters and frauds

Photos: Itzik Belinsky

The apartment in the Neve Achiezer neighborhood of Bnei Brak looks like a typical rabbinic home: A dining room walled with seforim, from floor to ceiling, shelves crammed into every available corner. But the seforim in this room are actually the main characters in some fascinating detective stories.

Rav Yitzchak Yeshaya Weiss, the rav of Neve Achiezer, is a famed mechaber seforim and posek renowned for his proficiency in halachic literature. He spent decades editing the writings of scholars from previous generations, and put out the legendary Torah journal Tzefonot (with his unforgettable friend, Reb Zusha Kinstlicher, ztz”l), featuring manuscripts of Torah giants.

Along the way he gained a unique expertise in discerning forged manuscripts, a skill that’s the fruit of tremendous Torah knowledge, proficiency in the history of seforim, and most importantly, a sharp eye for tiny details that others might easily miss.

In the antiques market, which is riven with forgers and counterfeiters, this combination of traits is vital. A person who is about to pay a few thousand (or even hundreds of thousands of) dollars for a historic manuscript would do well to verify it’s neither a forgery nor a copy.

Rav Weiss has become an address, a rav hamachshir of sorts, in this rarified market. Many dealers and clients won’t close a Judaica deal before getting his stamp of approval — and many forgers see him as their nemesis. Many fraudulent deals find an early end here in his living room, where he spares trusting would-be buyers from falling into a painful — and expensive — trap.

On any random day you can find multiple manuscripts on the Rav’s desk. His nod of approval can transform those pieces of paper into treasures worth a hefty fortune. Rav Weiss’s clues in the authentication process can be as minor as a blurred word, ink stain, or hole gnawed by a bookworm. But his scholarship and intuition are just as valuable in this unique type of detective work.

“The box was etched with the words: ‘Donated to the beis medrash of the Rav Chasam Sofer, Pressburg 5591 (1831).’ Although I do not deal in antique objects, I knew that in 5591, Rav Moshe Sofer was not yet known as the Chasam Sofer”

Forging for Bread

“The first thing you need to know,” Rav Weiss tells us, “is that not all forgeries are the same. Some are done in an amateur fashion, but others are created with great skill.”

In contrast to professional forgeries, there are amateur ones that are quite easy to deduce — if you have the requisite knowledge. “An antiques dealer showed me an ancient tzedakah box made from copper, which supposedly had a prestigious provenance. The seller was an elderly man who bought it from someone whose grandfather would carry it around each day in the Beis Medrash in Pressburg during Vayevarech Dovid. It was claimed that the mara d’asra, the Chasam Sofer, ztz”l, gave tzedakah in this box each day. The box was even etched with the words: ‘Donated to the beis medrash of the Rav Chasam Sofer, Pressburg 5591 (1831).’

“Although I do not deal in antique objects,” Rav Weiss says, “I knew for a fact that in 5591, Rav Moshe Sofer was not yet known as the Chasam Sofer. The title was only bestowed on him in 5603 (1843), when his chiddushim on Torah were first printed.”

Rav Weiss has had an affinity for seforim and manuscripts from a very young age. It’s in his blood — his father, the gaavad of Neve Achiezer ztz”l, was a well-known reviewer of seforim, and his pieces in chareidi media about seforim won acclaim for their encyclopedic knowledge and keen, critical eye. He managed to save some rare manuscripts during the Holocaust, and his young son found them a source of curiosity and fascination.

Later, Rav Weiss learned under a number of mentors, such as the rosh yeshivah of Tchebin, Rav Baruch Shimon Schneerson, who was also known for his sharp eye and knowledge of seforim.

“Once, I was leafing through an old sefer, and I sensed that there was something strange about it. Just then, the Rosh Yeshivah passed by, and he smiled. It turned out that it was a plagiarism, which is literary theft. The author simply ‘stole’ the entire compilation, word for word, and affixed his own name to it. The Rosh Yeshivah explained to me that we have to judge him l’kaf zechus. Back when the author performed his subterfuge there were rabbanim who were literally starving. Their plagiarism bought bread for their children, plain and simple.”

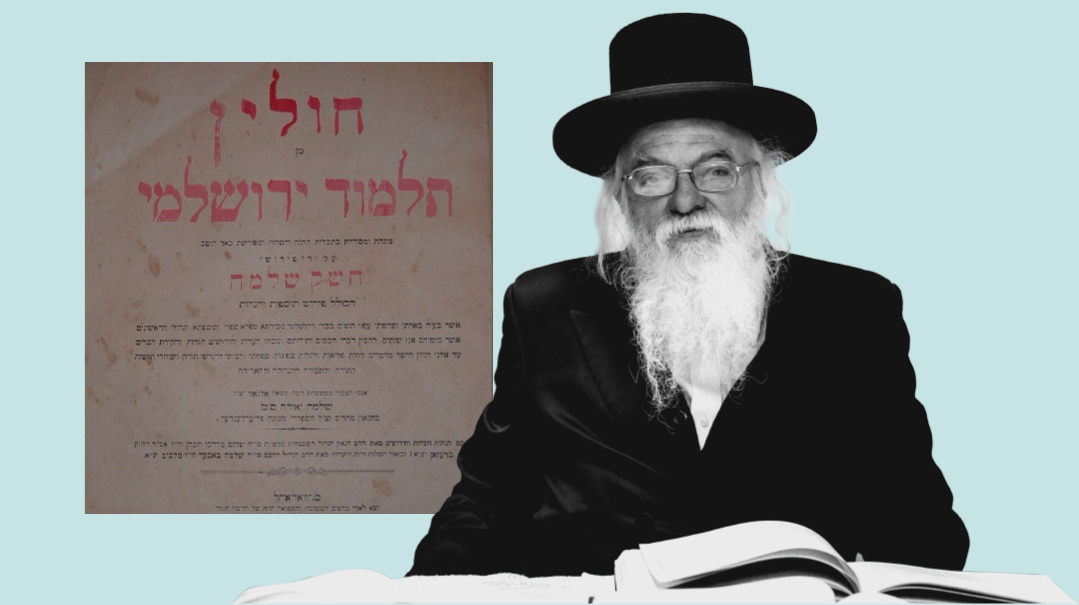

Nowadays, Rav Weiss says, it’s become easier than ever to pass along a forgery without detection. “There’s a famous forgery of the Talmud Yerushalmi on seder Kodshim created by a first-class forger. Were it to be produced today, I’m not sure it would have been identified as a fake — because you need a very erudite Torah scholar to find the flaws.

“Back when it was being circulated, the Rogatchover Gaon proved it was a forgery, drawing on the fact that in each of the six Seder Mishnayos in the Yerushalmi there is the name of an Amora that is not mentioned in the other sedorim. I don’t think there is anyone in our generation who would notice such a thing. The last one was perhaps Rav Chaim Kanievsky ztz”l.”

Rav Weiss had personal experience with Rav Chaim’s famous powers of near-instantaneous recall. Back when he served as editor-in-chief of the annotations on the Machon Yerushalayim’s Minchas Chinuch, he’d consult with Rav Chaim to resolve missing or questionable sources. “It was amazing to see how Rav Chaim scanned the entire Shas in his head, and murmured, ‘Bavli — no. Yerushalmi — no. Tosefta — no.’ Then he asked if he should also ‘search’ in the midrashim. I told him that the Chinuch does not cite midrashim, so it wouldn’t be necessary.”

Rav Weiss witnessed similar feats from another famous scholar. “While I was still a bochur, I printed the sefer Ohel Dovid, by Rav Dovid Deitsch. I learned then in Tchebin and asked Rav Avraham Genichovsky who could advise me about sources that I hadn’t managed to locate. He sent me to Rav Ben Tzion Abba Shaul, the Ohr Letzion, who stood up and said: ‘It’s not in Berachos. Not in Shabbos. Not in Eiruvin’ — he also just scanned all of Shas, one masechta after another.”

Mishpacha’s rabbinic team examines Rav Weiss’s evidence. (Above) A forged letter supposedly from Rav Yechezkel Abramsky

The Bookworm’s Clue

Rav Weiss still remembers the “ancient letter” he was shown — a request from the seven tovei ha’ir of Lublin to the parnassim of the Krakow community. In that letter, the parnassim describe an indigent elderly resident of their city, Lublin, who had a wealthy son in Krakow. Despite his poor father’s pleas, this son refused to help him with tzedakah. Therefore, the parnassim of Lublin asked the parnassim of Krakow to compel the son to support his father. The letter was adorned with the signatures of the parnassim, but surprisingly enough, there was also another signature: that of the Chozeh of Lublin.

“This was very puzzling to me,” Rav Weiss says. “Much is known about the holiness and piety of the Chozeh of Lublin, but I’d never heard of him liaising with the parnassim of the city to deal with the needs of the people. Just the opposite — the Rav and parnassim of Lublin were no admirers of the Chozeh and his chassidim, and the gabbai of the chevra kaddisha refused to give him a prestigious burial plot.”

Upon closer examination of the letter, Rav Weiss noticed that the signature of the Chozeh was at the end of the line, unlike the others which were at the beginning. The color was different as well. Clearly a forger had added an admirably accurate replica of the Chozeh’s signature to an old, original document. But even though the signature looked right, he’d done a sloppy job with his history. Apparently he figured that the average buyer would be thrilled to own the holy signature that this letter ostensibly bore.

Then there was the Shulchan Aruch Yoreh Dei’ah, printed in Amsterdam in 5471(1711) that someone brought to Rav Weiss. “It was in excellent condition, without a single stain or crease, as if it had been printed that day,” he remembers. “It had a wood and leather antique binding. In the middle of the first title page was an inscription in a nice handwriting remarkably similar to the handwriting of the Maggid of Mezritch. I didn’t have a chance to photograph it, but it was a long inscription testifying to someone’s proficiency in shechitah and exhorting him to study the relevant halachos.

“The inscription was signed, Hakatan Dov Ber the son of Moreinu Harav Avraham (Maggid Meisharim), the Kehilah Kedoshah of Mezritch. The handwriting and signature are remarkably similar to the writing attributed to the Maggid of Mezritch, in a ksav semichah given to a shochet whom he described as ‘HaTorani Hamufla Moreinu Harav Reb Yov Tov ben Moreinu Menachem Nachum,’ a copy of which was published in a number of places (for example, see the sefer of Y. Alfasi, Hachassidus Midor Ledor [Yerushalayim 5755] p. 58).

“But,” Rav Weiss says, “it was very puzzling, and very suspicious, that this sefer, which the shochet was supposed to learn daily, had survived in such a wonderful condition.”

Rav Weiss examined the inscription closely and realized that it was almost a perfect replica of the historical ksav semichah attributed to the Maggid. Almost — but not quite. The order of the phrases was different, and additional words were added regarding the Shulchan Aruch and the daily study.

But it took three small holes to establish without any doubt that the inscription was a forgery. “On the flyleaf where the inscription appears, I saw three small holes, apparently made by bookworms. But the adjoining cover, and the title page on the other side, were smooth as a mirror, and no worm has gotten near them.

“If this is not a forgery,” he says wryly, “then it’s a wonder of nature: How could a worm penetrate a book’s inner flyleaf without penetrating the pages adjacent to it?”

Then Rav Weiss examined the back cover, where he found three worm holes that penetrated the body of the sefer and ran along several dozen pages.

“I realized what had happened here: The forger found a sefer that no one ever learned and no one ever enjoyed. The front flyleaf probably had a listing of the owners, so he tore that page out. Then he took the smooth, clean page from the back of the sefer, and copied the ‘inscription’ — basing it on the historic ksav semichah — and then planted it at the beginning of the sefer, where an inscription from the holy Maggid would be fittingly placed.”

It took the nibbling of some ancient bookworm — and a very keen eye — to reveal it as a fake.

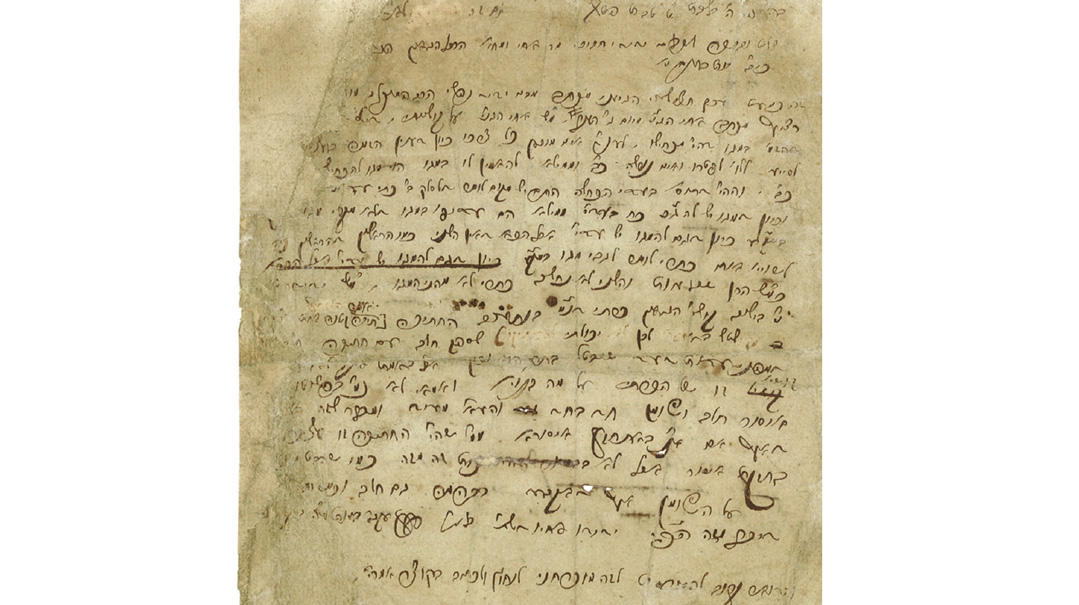

A document allegedly written by Rav Akiva Eiger. The greater the name familiarity, the more valuable the paper

Nefarious Agendas

The forgery underworld is also populated by people who aren’t looking for money; they have more nefarious agendas. This type of forger might create a pseudepigraph, meaning they write entire compilations and then claim that they are ancient writings.

Why would someone try to pass off his own work as an ancient composition? “For the most part, these are forgers with personal agendas,” Rav Weiss explains. “Take, for example, the forgery of the sefer Shu”t Besamim Rosh, which was done with the malicious intent of deceiving people about the real halachah. This forgery is probably the most famous, and notorious, of its type.”

The sefer was written by a rabbi and a closet maskil named Shaul Berlin. Berlin was a talented scholar who wanted to advance the haskalah agenda, and he did it by producing a particularly evil forgery: a sefer that looked like a compilation of halachic responsa from an ancient time. In the introduction, he described that the person who had compiled these questions and answered them was none other than the Rosh, and, he claimed, the work was edited by a Sephardic chacham named Rabi Yitzchak di Molina, who was not well known and lived in the generation of Rav Yosef Karo. Somehow, the story went, this manuscript had made its way into his hands.

In addition to the teshuvos of the Rosh and the annotations of the mysterious Di Molina, Berlin added his own commentary, entitled Kasa Deharsena, in which his “enlightened” theories peek through the historic veneer. Among other things, there are strange leniencies allowing one to shave one’s beard with a razor after cutting it with a scissors, so that there should not remain a shiur; that there is no longer a need for sechirus reshus for an eiruv chatzeiros because we in any case live among non-Jews; a translation and shortening of the tefillah; permitting yayin nesech and milk from non-Jews in current times; permission to conduct weddings and to eat on Tishah B’Av in our times, and much more. And all this was cited in the name of Rabbeinu the Rosh.

It didn’t take long for a few sages to discover the trickery and launched a vigorous campaign against the sefer. Yet the presentation was so skillful that several vaunted Torah scholars took it for a valid sefer.

A Forger in Shidduchim

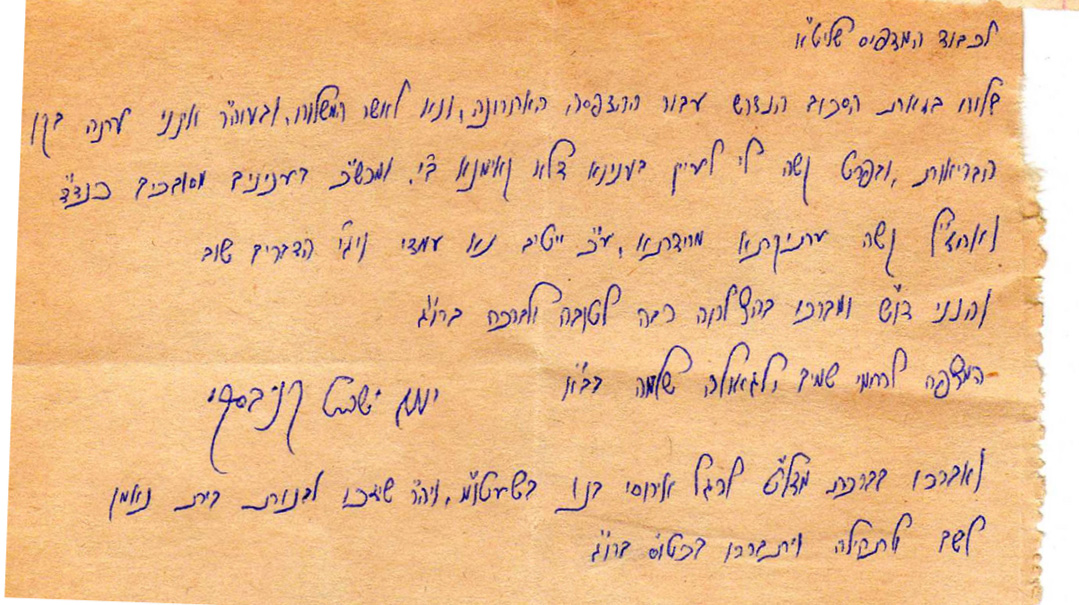

While forgers like Berlin were motivated by ideals — twisted as they may have been — today’s forgers, for the most part, deceive for financial gain. “Here,” Rav Weiss points to two manuscripts. “Do you see this? These carry every sign of being authentic manuscripts of the Steipler and of Rav Yechezkel Abramsky. One day, 30 years ago, a young man, a talmid in a famous yeshivah, came and asked me to affirm the provenance of these two manuscripts. He wanted my approval so he could sell them.

“Something about the date on the manuscripts didn’t sit right with me. I went to Rav Avraham Yeshaya Kanievsky, Rav Chaim’s son, whom I am friendly with, and asked him to examine the manuscript attributed to the Steipler. He peered at it, then straightened up and told me, ‘My grandfather never wrote Hashem’s Name, and he was careful never to connect the letters alef and lamed in the middle of a word.’ That was the proof I needed. It was definitely a forgery.

“I then found out that this bochur had already sold dozens of these forged ‘manuscripts.’ He also sold old seforim in which he’d added names of various gedolim to the flyleaf, so it looked as if these seforim had once been part of their collections. I confronted him before the dayan Rav Menachem Mendel Shafran, and there, he burst into tears and claimed that if it was publicized that he dealt in forgeries, it would affect his shidduchim. Said Rav Shafran, ‘On the contrary, if you are in shidduchim, it is even more important for people to know who you really are.’

“Ultimately, the bochur pledged never to deal in forgeries again and also committed to collect the forgeries — about 15 items — from the dealers he had sold them to. To this day, I think there are still forgeries from him in circulation.While we were at Rav Shafran, we asked him to show us how he managed to create such accurate forgeries. He calmly sat down and demonstrated for us, mimicking the handwriting of the gedolim perfectly. Then he took a second pen out and signed with a different signature. It was shocking to see how easy it is to forge.”

That bochur’s forgeries were far from the only ones Rav Weiss encountered. After he unveiled a disturbing number of deceptive manuscripts, he decided that he had to warn the public. He consulted with his rebbi, Rav Moshe Halberstam ztz”l, ravaad of the Eidah Hachareidis, who ruled that he had an obligation to get the word out — and let the forgers know that someone was on the alert.

Rav Weiss wrote a very piercing article in the Bobover Eitz Chaim journal, exposing a number of forged writings that had come to him. In the article, Rav Weiss detailed a new phenomenon in the murky world of forgeries: “The forgers took a volume of a manuscript by a gaon who is not so renowned, and therefore, the value of his written work is not high. They erased his name from the sefer and replaced it with the forged signature of one of the gedolim of that generation, whose Torah works were in high demand.”

Which begs the question: Who can determine the value of the chiddushim of a Polish gaon? How would a forger determine which byline would net him more money?

“Oh, it’s a simple test,” Rav Weiss says, smiling. “The dealers call it the Itzkowitz test. You go into the Itzkowitz shtiblach during Minchah, stop a few passersby, and ask if they’re heard of this Polish gadol. The more yeses you get, the higher the price for his seforim. It’s that simple. The One Above can appreciate the true value of a person’s deeds, but when it comes to seforim, for the most part, the sticker value of your writings boils down to name recognition.”

The Steipler’s grandson discovered this forgery, because he knew his zeide never wrote Hashem’s name and was careful never to connect the letters alef and lamed in the middle of a word

Revealing the Hidden

Rav Yitzchak Yeshaya Weiss’s work is essentially divided into two parts: the part that he has to do and the part that he wants to do. While the exposure of forgeries is something he does reluctantly, the revelation of heretofore hidden writings is something that brings him satisfaction and delight.

In addition to the manuscripts that he deciphered and edited, which appeared in Tzefonot, the Rav has also edited a number of seforim. For example, a few years ago, a new edition of the sefer Arugos Habosem, by Rav Michoel Bachrach, the rosh beis din in Prague, was published. For nearly 200 years, this manuscript remained shrouded in oblivion. “But then a dealer came to me with a faded packet of writings that a Jewish man had found while touring Prague,” Rav Weiss recounts, “and brought them to me to be deciphered. After studying them and comparing them to other historical manuscripts, I was able to conclude that some of the writings were from Rav Bachrach.

“Then, during a random conversation with Rav Yosef Buxbaum of Machon Yerushalayim, I learned that the team at his institute was about to publish a new edition of Arugos Habosem. I called the Machon directly and dropped the bombshell. With great excitement, Rav Buxbaum stopped the presses, and had his team add the latest revelation at the end of the volume. Thus, the lost artifact was restored to the rightful owners, and Klal Yisrael merited a complete sefer.”

Rav Weiss is likely the only person in the world who received three haskamos for a single work from the Steipler. It happened when he was about to publish the Megaleh Amukos, prepared from manuscripts written by the author himself and those of his talmidim.

Rav Weiss approached the Steipler for an approbation, and since the Steipler did not see well, he put his eyes extremely close to the paper — so close that his beard got stained blue from the ink.

“He made several corrections, crossing out and rewriting,” Rav Weiss remembers. “Then he said he had to redo it, because a letter with more than five corrections is not respectful. So he rewrote the entire letter. Then, when he signed it, he mistakenly put the signature upside down. So he copied the whole letter over a third time. That’s how I got three letters of approbation for a single sefer from the Steipler!”

TERMS TO KNOW

Genizah in a binding: For many years, printers would bind seforim with used pieces of parchment in order to save on costs. Often, the binders of sifrei kodesh would put Torah writings in the bindings. This is how the bindings of old seforim became a veritable treasure trove of ancient writings for those with the tenacity and knowledge to carefully disassemble the seforim and reconstruct the scraps inside. (The Avnei Nezer of Sochatchov zy”a writes about this at length in his teshuvah sefer [Yoreh Dei’ah 376]).

Incunabulum: The term for a sefer printed when printing was in its very early stages, until the year 1500.

Watermark: At the beginning of the printing industry, each print house marked is pages with a watermark, a transparent seal that became visible when the page was held up against the sun (similar to figures that appear on currency notes today). This technique made it very difficult to forge documents.

Pseudepigraph (from the Greek words pseud — false and epigraph — writing): A form of literary creation attributed to an earlier period than it was actually written in, or that is attributed to another writer, usually more respected and reliable than the actual author.

Plagiarism: Literary theft. Copying thoughts and expressions of an author and presenting them as one’s own. The roots of this word come from the Latin plagiarius, which means to snatch. This word served, until the end of the 17th century, to describe kidnappings of children and slaves, as well as literary theft. In the view of historians, comparing the act of literary theft to the abduction of a slave/child indicates the tremendous importance that was attributed to creative work and illustrates the perceived severity of the act.In the Middle Ages, people who wrote songs and poems tried to overcome this problem by codifying their names in their creation. The most accepted way to do this was using an acrostic — beginning each stanza of the song with a letter of the composer’s name. (Lecha Dodi is a famous example of this technique.)

—Yisrael A. Groweiss contributed to this piece

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 913)

Oops! We could not locate your form.