Is it Listed?

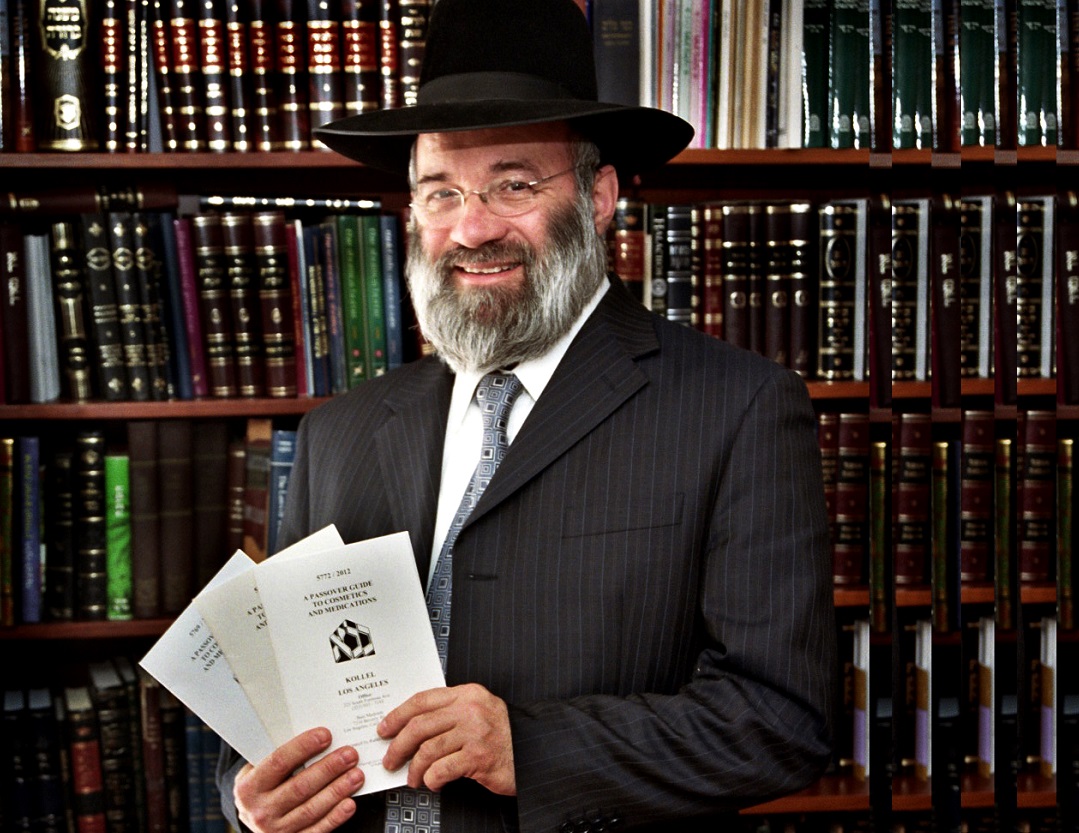

What started as Rabbi Gershon Bess’s five-page list has grown to a full-sized book that Jews all over the US consider the definitive guide to Pesach-approved medications and cosmetics. While a dog might not eat that mascara, Rabbi Bess wants to make sure everything in your house is chometz-free

C

ertain questions are inevitable amid the frenetic activity that envelops frum homes during the week before Pesach: “Who wants to help move the fridge?” “Do we have enough eggs and potatoes?” and “Can you take the car to get cleaned?”

And then there’s “Who knows where Rabbi Bess’s list is?”

What Rabbi Gershon Bess initiated some 33 years ago as a five-page list has developed into a full-size book, an authoritative guide to medications and cosmetics approved for use during Pesach.

The list began as a project of the Kollel of Los Angeles, where Rabbi Bess was a long-time kollel member, and he has continued to expand it throughout his 24 years as the rav of Kehilas Yaakov in Los Angeles and a leading posek on the West Coast. Seven years ago, the Baltimore-based Star-K kashrus agency, founded and led by Rabbi Moshe Heinemann, joined the kollel as a cosponsor of the book, which now features information on several thousand products.

Although Rabbi Bess stresses that he isn’t “the last word,” only perhaps “one of the words” in the area of Pesach medications and cosmetics, he does believe that the information he presents is perhaps relevant today more than ever for the frum consumer. He recalls with a chuckle that the idea for the list was inspired, most fittingly, by a Yiddishe mamme. “You know, in the old days, everything was forbidden on Pesach, so I asked my mother, ‘Okay, we can’t have anything in the house, but … if it’s not chometz, then can we have it? Like, say, Ivory soap. If I find out it’s not chometz, then can we have it?’”

Unfortunately, he observes, since those days, the communal pendulum has swung decidedly in the other direction. As more and more commercially produced kosher l’Pesach products crowd the market, the convenience and wide selection of prepared foods have drawn consumers away from the instinctive reluctance generations of Jews felt toward bringing items produced by others into their homes on Pesach.

Scraping Down the Walls

One casualty of the trend toward commercialization, Rabbi Bess believes, is the deep sense of cautiousness that Yidden have always displayed regarding even the remote possibility of chometz in their homes on Pesach. That zealousness was rooted in the halachah proscribing the ingestion of a food containing even a mashehu (minute amount) of chometz, a level of prohibition that does not apply to other forbidden foods. Innumerable practices unique to Pesach developed due to this attitude of extreme caution, from discarding any foodstuff that touched even a newly swept floor to scouring every last nook and cranny for vestiges of chometz.

The list deals exclusively with medications and cosmetics, none of which are edible in the conventional sense, but which may contain some form of alcohol or other chometz derivative. Even though any chometz these products might contain would surely be what halachah refers to as nifsal mei’achilas kelev (inedible even for animals), the list reflects the traditional attitude that Pesach calls for heightened standards, and for taking even minority halachic opinions into account if possible.

Rabbi Bess finds it disheartening when Pesach product lists seem to issue blanket heteirim for all sorts of cosmetic products based on the fact that they are nifsal mei’achilas kelev. “Does that mean,” he asks rhetorically, “that what my grandmother and great-grandmother, and yours, did — there was nothing to that? Did they think that shoe polish and soap were edible, and now someone came along in our day and discovered that they’re not?

“Whether or not it had an absolute halachic basis, this was the minhag Yisrael; people would literally scrape the walls of the Jewish home before Pesach, and so on. It’s an unfortunate development that there are now lists that say you can use this brand of cornflakes or ketchup or mustard because, well, this or that ingredient is bateil [halachically annulled due to its minuteness]. I’m really concerned that the way things are going, this is the last generation in which there’ll be a Pesach aisle in Ralph’s or ShopRite because all the year-round products will have been rendered fit for use on Pesach.”

Rabbi Bess’s stance requiring even nonedible products to be chometz-free — at least l’chatchilah — has found support at the highest levels of the Torah world. “When I was in Eretz Yisrael, I asked Rav Meir Soloveitchik whether I should continue to put out the list, because frankly it’s a great amount of work, and if it’s not necessary, I don’t want to do it. He told me his father wouldn’t buy medication after Pesach from a pharmacy unless he knew it was owned by a frum pharmacist who had sold the merchandise before Pesach. The prohibition on chometz she’avar alav haPesach (chometz in the possession of a Jew on Pesach) is rabbinic, yet the Brisker Rav wouldn’t purchase even a medication containing chometz that had been in a Jew’s possession over Pesach.

“When I spoke with Rav Elyashiv ztz”l about the list, he said it’s definitely the right thing: ‘L’chatchilah avada darf mehn zohir zein [L’chatchilah one must certainly be careful about this].’ Rav Wosner yblcht”a holds the same way. Interestingly, Rabbi Moshe Heinemann asserts that if we don’t continue to put out the list, it can to lead to situations of pikuach nefesh [life-threatening cases], because there are some ehrliche, fartzeitishe [old-time] Jews who won’t take vital medications unless they see them on an approved list.”

Back to the Past

The standard year-round kashrus certification process involves on-site inspections of production facilities and the various ingredients before a certifying agency will grant its approval, but that’s not the case for the products on Rabbi Bess’s list. Compiling the list requires countless hours of research by Rabbi Bess and those assisting him — which, in recent years, include Nitra Dayan Rav Hillel Weinberger and other rabbanim associated with the Hisachdus Harabbonim. Each year, in the months leading up to Pesach, he writes to hundreds of companies, asking them to reply in writing whether their product contains any traces of the five species of grains that can become chometz.

In his letter, Rabbi Bess makes sure to state that any information provided will be distributed to individuals suffering from celiac sprue, an allergy to gluten found in these five grain species, which is true. “Years ago,” Rabbi Bess recalls, “a lady in Montana asked to be put on our mailing list because she read that the health information provided by the Kollel of Los Angeles is more accurate than that put out by the medical establishment.”

Rav Moshe Feinstein held that one may rely on a company’s written response to such an inquiry, especially now that there is a climate of concern for allergic conditions and the possibility of lawsuits by those who suffer from them.

Only a certain percentage of these companies, however, respond to his inquiries. “Some companies won’t answer us at all due to corporate concerns about liability; in other cases, the legal department will only allow a company to answer us on the phone but not in writing. The ones that do answer are very careful in their replies. For example, they’ll respond that ‘this product contains gluten but it’s only four or ten parts per million, and thus it’s safe.’ Occasionally, we’ll get a letter from a company that’s impressive in the thoroughness of the response.”

Corporate takeovers also complicate matters — such as when a pharmaceutical giant like Pfizer takes over other companies and prevents them from responding to kashrus queries as they have in the past.

Rabbi Bess stresses that he doesn’t claim nonfood products containing chometz that is nifsal mei’achilas kelev are squarely within the prohibition of chometz according to most poskim. “So maybe we don’t pasken like the Sho’eil U’Meishiv [see sidebar]; Rav Moshe Feinstein certainly held that medications containing chometz may be used. But let’s not make our grandparents into delusional people who didn’t know all these products weren’t edible, or suggest that the Brisker Rav, who was makpid on chometz she’avar alav haPesach on pharmaceuticals, didn’t know the facts, but now we know otherwise.

“As the Satmar Rav once said, if you have to look up the halachah to be machshir a mikveh, it’s no good. In other words, a mikveh has to be kosher without the Shulchan Aruch, it has to be one that has no questions on it. The same is true, to my mind, when it comes to Pesach. We see the stringencies Klal Yisrael has had; just look at the discussion in halachah about the custom not to eat dried fruits because sometimes they would use chometz in the drying process.

“I see this issue as part of a whole trend toward saying everything’s okay despite a longstanding minhag Yisrael to be stringent when it comes to Pesach.”

Would a Dog Eat That?

To explain why chometz issues arise not only with products taken orally, such as pills and potions, mouthwash and toothpaste, but also with products far removed from ingestion, like shoe polish and mascara, Rabbi Bess cites a number of considerations. One is that the Sho’eil U’Meishiv, a leading posek of his day, held that the exemption from the chometz prihibition of items that were nifsal mei’achilas kelev only applies to items that were originally fit for consumption but have become spoiled; it does not apply, however, to products that were never intended to be eaten as foods. Rav Shlomo Zalman Braun, author of the contemporary halachic work She’arim Metzuyanim B’halachah, cites the Sho’eil U’Meishiv’s view in the context of medications and cosmetics on Pesach.

Rabbi Bess also points out that in the Biur Halachah on hilchos Pesach (Orach Chayim 442), the Chofetz Chaim seems to suggest that the rule of nifsal mei’achilas kelev doesn’t pertain when otherwise edible chometz is rendered inedible through mixture with other inedible ingredients. Using the example of pouring kerosene into a loaf of bread, he says that the bread does not lose its status as a foodstuff, and thus remains prohibited. This would seem to apply to various cosmetic and medicinal products that contain chometz, such as alcohol, which in isolation would be edible if not for the presence of other substances that make the entire mixture unfit for an animal.

Other factors bearing on the halachic status of medications and cosmetics are the fact that the denatured alcohol present in perfumes and other products can be restored to regular alcohol; that some authorities hold that by ingesting products like toothpaste and mouthwash, one grants them the status of foodstuffs (using the principle of achshivei) and thus, the usual halachos of chometz apply; and that according to some views, external application of an inedible lotion is tantamount to internal ingestion (sichah k’shtiyah).

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 451)

Oops! We could not locate your form.