In the Nick of Time

David Shishlov refused to abandon Mariupol until he took a direct hit

David Shishlov considers himself a walking miracle. Literally. Having been airlifted from Ukraine and hospitalized for the past six weeks at the Reut Rehabilitation Center in Tel Aviv, David is recovering from a spinal injury sustained in the shelling of his home town of Mariupol, where overwhelmed, equipment-strapped caregivers told him he’d be paralyzed for life.

David was born and bred in Mariupol, an industrial city just 37 miles from the Russian border. His family, like most of Mariupol’s Jewish families, wasn’t religious to begin with, but became closer to Yiddishkeit through Chabad, and through David’s own education in the Chabad school system. His mother, a supermarket manager, and his brother joined him on his religious journey; his father worked in the Azovstal steel plant before it was seized at the end of May, marking the Russian capture of the coastal city.

“Rabbi Cohen transported us to a new reality, showing us the beauty inherent in Judaism,” David says of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Cohen, the city’s Chabad shaliach.

While his mother was worried about him going out in public with a yarmulke and tzitzis, David discovered that people were more curious than antagonistic. He would engage people who barely knew they were Jewish in meaningful discussions, and even encouraged several grown men to undergo bris milah.

“One of them told me, ‘I can’t believe I’m about to enter the covenant of Avraham Avinu here in Mariupol, after years when I didn’t dare tell anyone that I was a Jew,’ ” David says.

In time, Shishlov became one of Rabbi Cohen’s most trusted and devoted assistants.

When Russia attacked Ukraine back in 2014, it had plans to occupy Mariupol as well, but the attempt failed and the city remained under Ukrainian control. Since then, the atmosphere has remained tense, as pro-Russian separatist forces have been tangling for years with the Ukrainian army and trying to achieve independence for the entire district. Yet for the most part, life continued and even flourished, with new parks and public infrastructure, and conservation projects for old buildings and historical sites. The Jewish community flourished as well.

But all that came to a screeching halt in February when the war broke out, when David’s family, like almost everyone else in Mariupol, became homeless refugees overnight.

Mariupol is a strategic asset for Russia, both because of its port and because it straddles the border between the separatist-controlled areas in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine and the part of southern Ukraine conquered in the first week of the war. Controlling Mariupol means controlling the land route to all the newly conquered territories, getting an important port city with a thriving steel and chemical industry, as well as full control of more than 80 percent of Ukraine’s Black Sea coastline.

“To be honest, I was one of those who believed a war would never happen,” says David. “Almost everyone I knew felt the same way. There would be a lot of talk, and then the aggression would peter out. Even when people started sounding the alarm bells and urged fleeing the country, no one wanted to hear it. Life was so comfortable in Mariupol. It was hard to believe that anything would actually happen.”

Besides, he was working with Rabbi Cohen, the city’s Chabad shaliach, who stayed upbeat, positive, and dedicated to his people.

“I remember getting into my car the first day of the war and listening to the news on the radio,” David relates. “I still couldn’t believe it. But when I stopped at a gas station and saw that the gas had run out, it started sinking in. When I passed the pharmacy and saw the massive line outside, I understood that this was for real. But we weren’t hearing explosions yet, and it didn’t occur to us to leave it all behind and run.”

WAR COMES TO MARIUPOL “To be honest, I was one of those who believed a war would never happen. Even when people started sounding the alarm bells and urged fleeing the country, no one wanted to hear it. Life was so comfortable.”

Bombardment

By the time the penny dropped, it was too late. In little more than a week, the Russians had encircled the city, cutting off its supply lines.

“This came as a complete shock to us,” says Shishlov. “We simply hadn’t registered that this was where things were headed. Some people still tried to escape in their cars, but most turned back after running into roadblocks or running out of fuel. It suddenly dawned on us that we could expect this situation to last for a week or even two. Even then, none of imagined that this would go on for months.”

Still, Shishlov has no regrets about not leaving sooner. “I think it was the right decision, especially because we had grandparents to look after, plus an entire community that was looking to me and my friends for help. In the early stages of the war, we distributed meals — nothing in great abundance, but enough to keep people from going hungry. But when the city’s electricity went down and we ran out of gas, we could no longer cook. Some of us went outside and set up barbecues, others lit bonfires and cooked their food over them. It felt like the Middle Ages. Whenever the shelling started up again, we had to drop everything and run for cover to underground cellars.”

In the first days of the war, Rabbi Cohen and David packed up all the shul’s sifrei Torah and stowed them away in the cellar so they wouldn’t be damaged by the shelling. The shul continued to serve as a depot for food and medicine, but then the food ran out, and the streets leading to the shul became impassable and dangerous. At that point they closed the shul for good.

The shelling, David relates, became a gradual reality. “At first there was only the sound of fighter planes flying over the city. It was threatening, but we didn’t think they’d actually harm us. But then the shelling on the outskirts of the city turned into actual bombardment.

“At first, we would only go down to the cellars when the sirens went off, but the sirens soon stopped working, and there was nothing to warn us of incoming mortars. Over time we learned to recognize the shriek and know where the shelling was directed at, based on the intensity of the explosions. One day I heard an earsplitting explosion and I knew it was very close. After the explosion there was a moment’s silence, and then I heard screaming and crying. It turned out that the mortar had fallen right behind our house and destroyed six connected houses. What I saw there was too much to bear — there were quite a few dead, including my friend’s eight-year-old daughter.”

By the next day, the neighborhood streets were filled with tanks, and the sound of artillery fire was deafening. “We hid in the cellars all day, but conditions became tougher by the minute. We had lost everything, we didn’t have electricity or water, and we had no way of communicating with the outside world. It was also freezing outside, and in the underground cellars it was even colder. The big miracle for us was that we had an underground water flow. In other areas of Mariupol, residents either had to go out for hours to search for water, use thawed snow, or collect the water from the drain pipes.

“Within a few days, almost the whole city was occupied,” David says. “Our neighborhood fell under Russian control, but we didn’t even know that, because we had no connection with the outside world.”

Left for Dead

And then the war caught up with him, too, in real time. One morning, as he went out with a few neighbors to cook some porridge over an outdoor bonfire, a mortar shell landed very close to where he was standing.

“There was an earsplitting roar and a massive shock wave,” he recalls. “I felt myself being hurled to the ground. I saw everyone around me falling as well. But while they jumped up and dashed for cover, I wasn’t able to get up. I heard the whistling of the mortars, knowing that another one could hit us any moment, but I couldn’t even cover my face with my hands, because I had no sensation below the shoulders.”

One of Shishlov’s neighbors realized the young man was lying in the open and was seriously injured. He alerted the others, and together they dragged him into the building, where they brought him into his house and laid him out on his bed.

“None of them knew anything about medicine,” he says, “but when they checked to see where I was hurt, they saw a deep gash in my back and realized a fragment of shrapnel must have entered my back and hit my spine, which is why I couldn’t move my arms or legs. In that moment everyone started crying. It was clear to them that I was paralyzed. Even my mother was afraid that the damage was irreversible.

“But I myself was a little calmer. I can’t explain it, but somehow I felt that everything would turn out all right. I figured that just as Hashem had arranged for the shell to land a few meters away and not hit me directly, and just as He made my friends notice that I was lying in the open, He would also help me regain the use of my legs. It was just obvious to me.”

Despite his optimism, fear began creeping into David’s psyche as the sensation in his body refused to return. “It was clear that I had to be evacuated to a hospital for treatment as soon as possible, but we didn’t know how to do this, because there hadn’t been ambulances in the streets for some time — or any vehicles, for that matter. The only mode of transportation was by foot, but I couldn’t walk.”

Meanwhile, others who had also suffered injuries made their way to the hospital on foot. They returned that same day, bringing back a chilling account of the state of affairs at the hospital and the staff’s inability to cope with the flood of patients. David realized his chances of receiving treatment were practically nil.

“Those were Mariupol’s darkest days. Injured people were stretched out on the sidewalk without anyone approaching to help them, there were dead bodies everywhere… and then, out of nowhere, a neighbor knocked on the door to tell me that there was a Red Cross ambulance outside that could bring me to the hospital. My mother put together the necessary papers in an instant, and the neighbor helped carry me out of the house. They brought me to the ambulance and laid me out on the floor of the vehicle: no bed, no doctor, no paramedic. We drove through the ruined streets, with my body being jostled back and forth on the metal floor.”

In the hospital, he discovered that his friends’ account of its state of affairs was heaven compared to the reality. “There was no electricity or medical supplies. The doctors who treated me told me that the shrapnel had in fact penetrated my back and they tried to extract it without anesthesia. The pain was unbearable. After repeated efforts, the doctors told me that they had failed to extract the shrapnel. They said to me: ‘All right, get up!’ I tried, but I couldn’t get on my feet. The doctors were unimpressed.

“One of them told me, ‘We get plenty of injured who can’t walk, but we set them on their feet anyway. They need to leave, there’s no one to look after them here.’

“Again, they tried to stand me up, but when I crumpled to the floor again, they laid me back on the bed. They explained to me that the shrapnel had likely come very near my spine, which is why I had lost sensory function in the left side of my body and motor function in the right side. In light of my condition, they agreed to let me stay in the hospital, but they said that my mother would have to stay there to look after me, because there were no nurses or staff members to do that.”

Buried Alive

Shishlov lay in the hospital for weeks, with the doctors making several attempts during that time to extract the shrapnel.

“I felt like my left leg was improving a little, and this encouraged me,” he says. “One day I even managed to wriggle my toes, and this filled me with strength and hope. I said to myself: ‘If before that I couldn’t move my toes and now I can, the same will probably happen with the rest of my leg. It’s just a matter of time and tefillos. Everything will be fine.’ ”

The hospital lacked even the basics — there was no food, no showers, and no water.

“There were volunteers, from Russia actually, who went between the beds and handed out food to the injured,” David relates. “It was just bread and vegetables, so I didn’t have to worry about kashrus. But I could barely eat. I was feeling really down about my condition. The doctors said there was no chance I would ever walk again, and my mother cried all the time. In addition to taking care of me, she was also worrying about her parents and my eight-year-old brother. From the beginning of the war, they stayed in their home in another part of the city along with my brother. At first we stayed in touch, and we brought them food and water, but later we lost touch because of the shelling.”

One day the hospital announced that a number of patients in particularly severe condition would be evacuated to a different hospital outside Mariupol, where they would be able to receive better treatment. The head of the ward decided to include Shishlov among the evacuees, and within hours he and his mother were in an ambulance on their way outside the city.

“This was on a Friday,” David recalls. “We arrived at the hospital on Shabbos night, and I was immediately wheeled into the operating room, where they finally extracted the shrapnel. It’s not that the situation improved all at once, but I was finally given painkillers, and I could also lie down on my back, something that hadn’t been possible before. My mother also felt better — after a month, she was finally able to get a shower.”

And there was another precious commodity at the new hospital — communication with the outside world. “We could finally speak with activists who were working on rescuing people from Mariupol. And so, from my bed, I resumed my unofficial responsibility for the community. I collected the names and addresses of the Jews remaining in Mariupol and helped arrange for shlichim to help them escape.

“The only problem was, it was impossible to leave the city. Russia had violated its own terms and the humanitarian corridors weren’t accessible. A few weeks later, when the shelling calmed down, and it became possible to leave Mariupol without danger, from a technical standpoint it was complex, almost impossible — the streets were ruined and piled with debris, shattered glass and destroyed utility poles. Our shaliach, Rabbi Cohen, arranged for rescue vehicles to get to every neighborhood and extract the residents. The Syrian community in New York also helped enormously. There’s no doubt that without their help, the number of casualties would have been much higher, because people’s lives were literally hanging in the balance.”

Several stations in southern Ukraine were set up for the Jewish refugees, where they received beds and kosher food, and from where they continued on to Europe or Israel. A minority decided for a variety of reasons to stay in Mariupol.

“We did what we could to provide them with food, medicine, and other necessities,” says David, “and Rabbi Cohen told them, ‘I will always remain your shaliach, and it doesn’t matter whether Mariupol is under Russian or Ukrainian control, or whether you’re here or in Europe or Israel — I’ll accompany you in spirit wherever you are.’ Ultimately, we reunited with my grandparents, father and brother, none of whom, baruch Hashem, were harmed by the shelling.”

According to Dr. Shmuel Barnai, a researcher on Russian affairs and faculty member at the Hebrew University and Ben-Gurion University, 90 percent of the city’s buildings are in ruins, including high-rise apartment buildings that collapsed and buried their residents alive. While the exact numbers are unknown, it is believed that between 20,000 to 50,000 of the city’s 450,000 residents died during the siege. In the course of the bombardment, the new shul and the Jewish community center were hit as well.

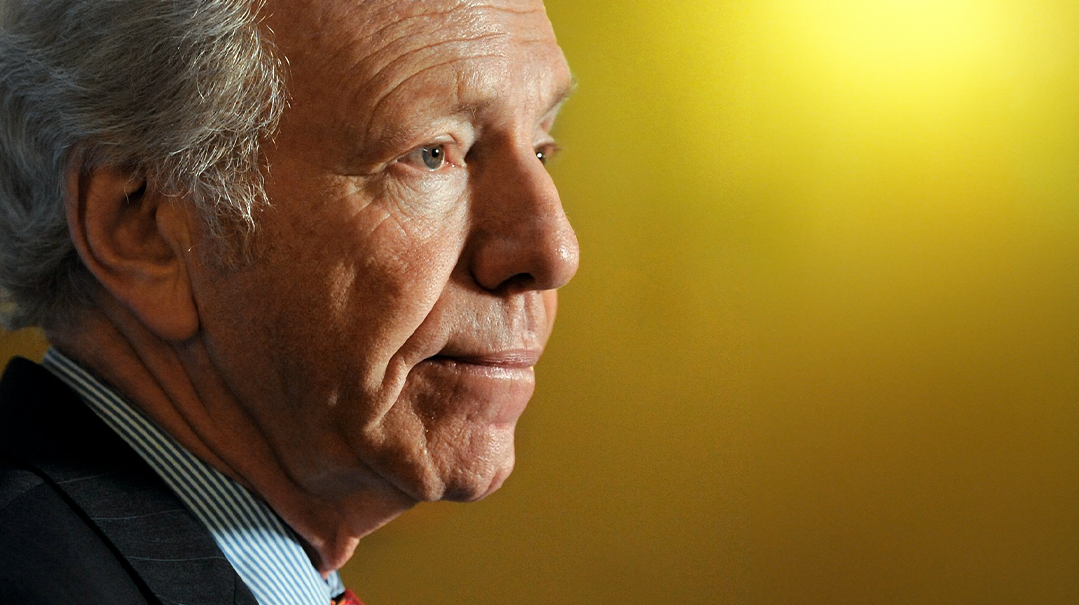

IN CALMER TIMES David Shishlov would become Rabbi Menachem Cohen's trusted and devoted assistant, engaging people in Mariupol who barely knew they were Jewish

Starting Over

And then it was David Shishlov’s turn to leave Ukraine — together with his parents, grandparents and little brother. Rabbi Cohen even arranged an entire row of seats for him, so that he could lie down during the flight.

Once in Israel, he was transferred directly to the Reut Rehabilitation Medical Center, where he’s on the slow road to recovery.

“I’ve been in Israel for a month and a half now,” he says, “and baruch Hashem, I’m seeing enormous miracles. I’ve regained motor function in the left side of my body, which means that I can move my hand, for example, even though superficial sensation is still gone. I can’t feel heat or cold, and when I cut my hand with a knife at breakfast, I couldn’t feel any pain. So I have to be extra careful and not hurt myself. The doctors keep reiterating how lucky I am, that if the shrapnel had hit one millimeter closer, it would have done irreversible damage to my spinal cord, and I would have been a quadriplegic for life.”

David believes that what’s kept him going is that he never felt abandoned. “I see clearly the Hashgachah pratis, how Hashem accompanied us the whole way and never left us for a moment,” he says. “It’s only when you come out of ruin and destruction that you can begin appreciating every little thing. I can’t tell you how excited I was when I realized I could drink unlimited clean, pure water. Or when a siren went off and it was just a smoke detector triggered by a cigarette.”

Shishlov’s parents and grandparents have settled in Haifa, along with a few other families from the community. They are all citizens now, no longer refugees. But starting over, even in the most friendly and supportive of countries, can be overwhelming. Mariupol might have become a symbol for heroism and resistance, but before their eyes, they saw everything they’d built turn to rubble, their past lives gone forever.

Russia has promised to rebuild Mariupol, the city they demolished, though it’s not clear how this can be done. The city’s industries and factories relied on outdated Soviet technologies, but as long as they existed, they worked efficiently. Now that the factories are destroyed, says Dr. Barnai, it will be very difficult to rebuild them from scratch. Furthermore, a large portion of the population has fled to southern Ukraine, and many others were forcibly transferred into Russia. Those who’ve remained are either the elderly or young people with low socioeconomic standing. So who will return to rebuild Mariupol? There isn’t a roof to sleep under in the entire city.

“The only way Mariupol can be rebuilt is if, at the end of this war, it’s decided that Ukraine will get the city back, along with an aid package from the West,” says Dr. Barnai. He believes that if Mariupol remains in Russian hands, they’ll likely report grandiose achievements, but in reality the city will remain a heap of ruined buildings and chaos in the streets.

“But we’re the lucky ones,” David Shishlov says. “We have a place to start over.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 921)

Oops! We could not locate your form.