Horror on the Hudson

| October 6, 2022“I have already been in this town for 24 hours and still cannot gather my strength to write my report”

Title: Horror on the Hudson

Location: Haverstraw, New York

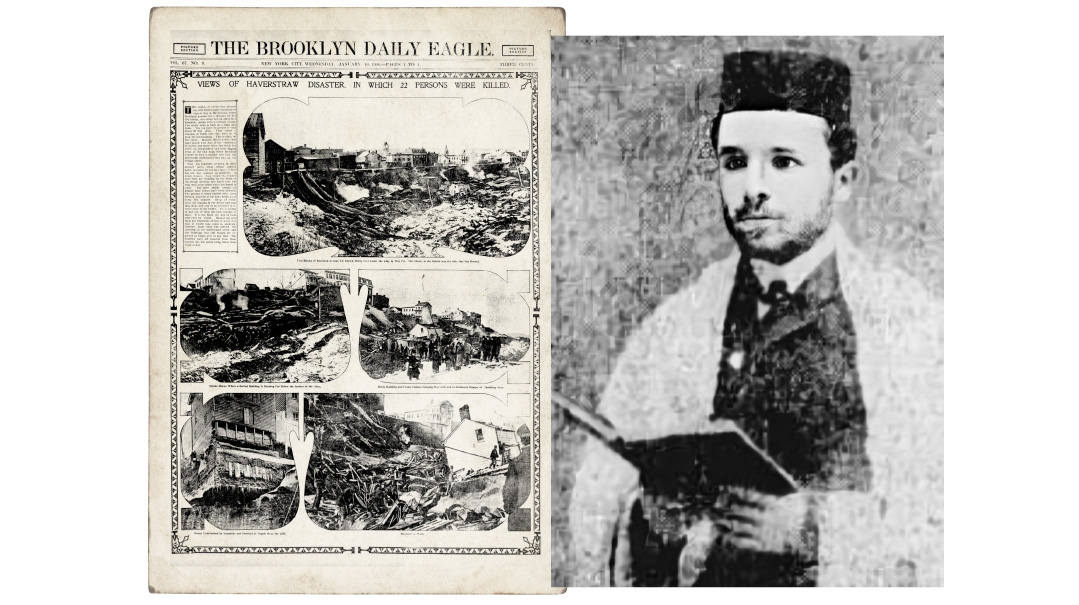

Document: The Brooklyn Daily Eagle

Time: January 10, 1906

ON January 9, 1906, Nosson “Nathan” Zvirin, a veteran writer and editor for the Yidishes Tageblatt, was sent to Haverstraw, a town 40 miles north of New York City, to report on a breaking story. The Minsk-born Zvirin, who had emigrated from the land of pogroms and chaos several years prior, was shaken to the core by what he found in Haverstraw.

Prior to submitting his article for the evening paper titled “Robbery That Leads to Murder: How the Earth Swallowed Up Jewish Families in Haverstraw,” he filed the following single-line dispatch: “I have already been in this town for 24 hours and still cannot gather my strength to write my report.”

Haverstraw is a town in Rockland County, located 11 miles northeast of central Monsey. While today home to a budding Torah community, Haverstraw was once renowned as the brick-making capital of the world. In the 1880s, 40 brickyards lined the town’s banks on the Hudson. During its dominant age at the turn of the 20th century, more than 3,000 laborers shipped out more than 350 million bricks a year, providing construction materials for many of the large cities of the Northeast. Ultimately it was Haverstraw’s over-industrialization that caused a major industrial disaster in 1906.

The story of how the city came to be called “Bricktown, USA” is told by exhibits in the Haverstraw Brick Museum. During the 18th century, the Hudson River Valley was found to contain a rare variety of yellow and blue clay that was optimal for brickmaking. In order to extract the highest-quality clay, mines were built alongside the factories on the banks of the Hudson River, tunneling underground within the city limits. The Industrial Revolution improved the brickmaking process. In the decades following the great New York City fires of 1835 and 1845, which destroyed hundreds of wooden structures, a large demand for safe and durable bricks emerged, and the industry in Haverstraw boomed. Many of New York City’s original turn-of-the-century brownstones were built with Haverstraw bricks.

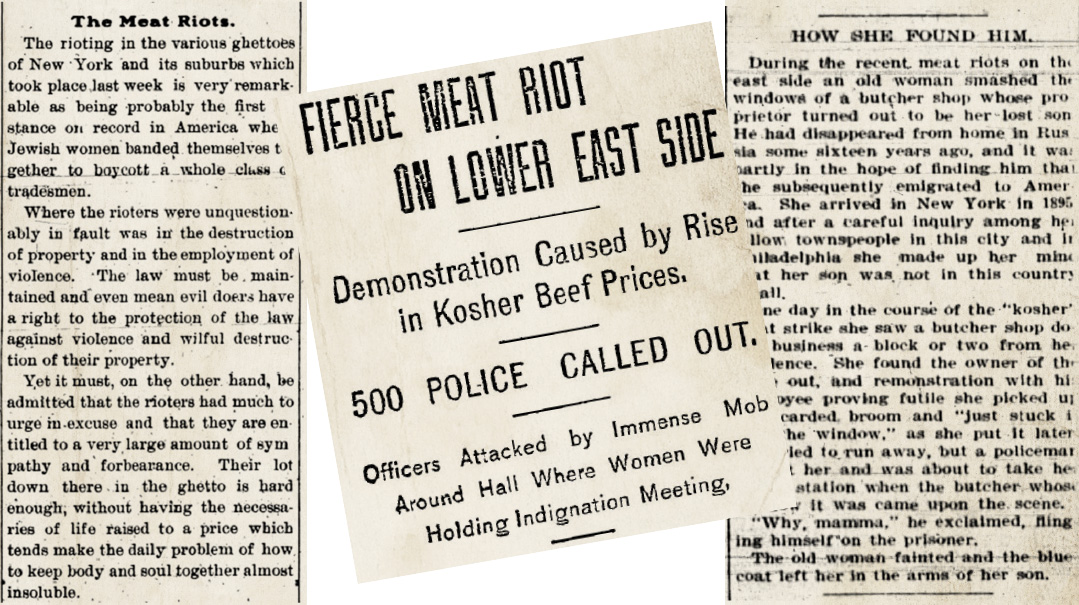

Many German Jews arrived in Haverstraw during the 1870s, soon followed in the 1890s by an influx from Eastern Europe as the Great Immigration picked up. These later arrivals took a variety of jobs in the service industry, which became increasingly necessary as the population grew. In 1877, they formed Sons of Jacob, the oldest Jewish congregation in Rockland County.

In June 1905, the community engaged the services of a 22-year-old immigrant rabbi named Rabbi Elimelech Adlin. It didn’t take Rabbi Adlin long to spring into action. In addition to using his skills as a shochet to improve local kashrus, he arranged the purchase of property adjacent to the shul for the town’s first Jewish cemetery.

While the town’s population grew to 6,000 by 1905, the brick manufacturers were tunneling further underneath it to extract more clay, until eventually the commercial district abutting the Hudson was essentially sitting on hollowed-out earth. The hazards were ignored as the town reaped the benefits of this boom.

Beginning in the 1890s, various signs pointed to impending disaster. On the morning of January 8, 1906, a wide crack that had appeared years earlier on Rockland Street began to widen, and by 4 p.m., the local fire department called for an evacuation of nearby stores and residents. Unfortunately, not all got the message, while others, citing the frigid weather, ignored the evacuation order and remained at home.

That night, a series of landslides engulfed 21 buildings, five streets, and two avenues, about a third of the village at that time, leaving a gaping chasm about 150 feet deep. The disaster was magnified when falling kerosene lamps set remaining buildings ablaze. The cold temperatures had frozen fire hydrants and caused several water mains to break. Only when the fire department from nearby Garnerville arrived was water pressure restored.

The tragedy claimed 19 lives, including eight Jews, among them Rabbi Elimelech Adlin, described in Yiddish newspaper reports as “a big lamdan and talmid chacham.” Rabbi Adlin had married for less than a year and left behind an expectant wife.

He resided on Rockland Street opposite the homes that were destroyed. When they heard the rumble, he and his congregant Wolf Provitz were among the first responders, saving one Mr. Cohen, then rushing back to the disaster to assist more people. They fell in action as a result of their heroic deeds. On January 18, the Yiddish newspaper Di Varhayt gave a brief obituary:

Rabbi Elimelech Adlin from Haverstraw, the heroic rabbi, Chazzan and shochet who perished in Haverstraw last week where 9 Jews were killed. The heroic rabbi went to rescue people when the houses fell into a 200-foot clay pit, and he was also buried beneath the ruins. Last Sunday his dead body was discovered, and his funeral was very large and moving. Everyone cried bitterly for the young life full of potential that went to waste. Rabbi Elimelech Adlin was found buried in the clay interlocked with the body of Chesel (Yechezkel) Nelson, the person whom he tried to save and on account of whom he paid with his life. The entire town went to witness the wonder of how these two men stood frozen in clay like a monument of heroism and as a reminder of the crime committed by the company who dug beneath the town and brought such a catastrophe on its residents. Rabbi Elimelech Adlin was merely 24 years old, he was a very intelligent young man, and since he came to town, he was so active that he earned the love and respect of Jew and Christians alike.

Recovery of the victims’ remains was delayed due to the continuing blaze and the hazards of the disaster site. The Jewish victims included local Haverstraw residents Wolf Provitz, Abraham Diaz, Abraham Silverman, Sarah Silverman, Herman (Haskel) Nelson and his son, Benjamin Nelson, who was a volunteer firefighter.

The final victim was David Adenbaum, a peddler from Brooklyn who had many customers in Haverstraw, Peekskill, and neighboring towns. He came to the area every Tuesday, but since that Shabbos was to be his son’s bar mitzvah, he had come a day earlier and tragically died saving others. Once recovered, David Adenbaum’s remains were brought back to Brooklyn for burial. Six of the seven remaining victims were buried in the first levayos held at the Sons of Jacob cemetery — which Rabbi Adlin had just opened a few weeks prior. Rabbi Bernard Drachman was among the many maspidim.

Adding Insult to Injury

Among those left injured and homeless in the disaster were a number of Jews, including Minnie Adlin, the expectant wife of Rabbi Elimelech Adlin. She hired a lawyer to file suit against the Excelsior Brick Company for negligence. Over the next seven years, she experienced what a local newspaper called “a travesty of justice” as her case was delayed, moved, and deemed a mistrial due to what seemed to be a miscommunication, a result of an incompetent translator hired by the court. A not-guilty verdict was handed down after the defense argued that Rabbi Adlin had put himself in danger by crossing the street to assist victims after hearing the commotion. Court documents describe Minnie Adlin balancing her baby on her lap as she suffered through years of shame and injustice. The lawyer for the defense made a particular effort to minimize Rabbi Adlin’s heroics, saying unashamedly, “Is it not the job of a rabbi to help those in need?” In 1913, lacking funds after several attempts at appeal, Minnie Adlin called it quits.

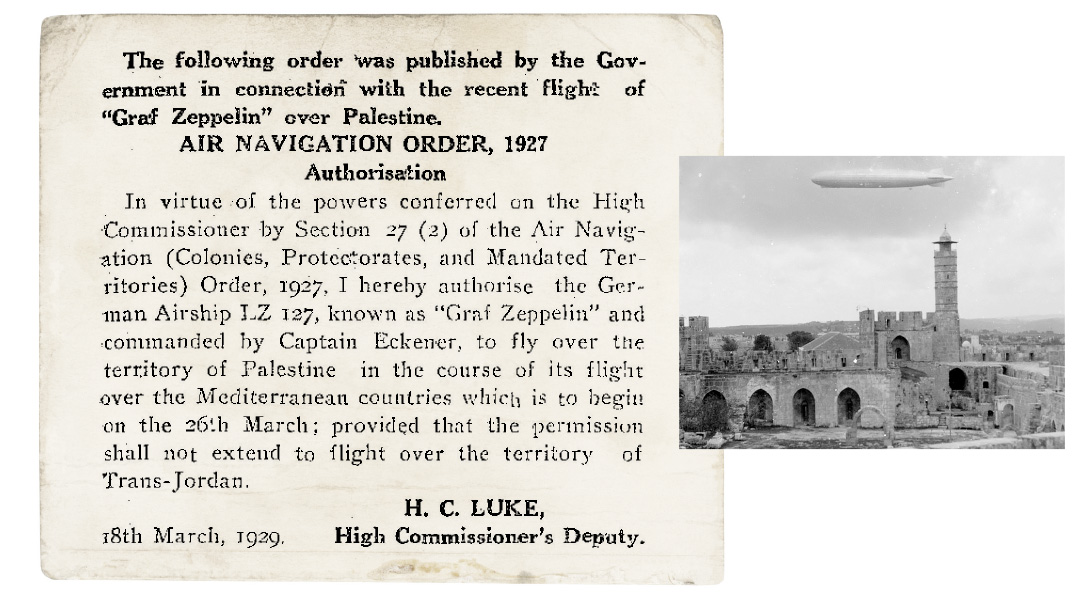

Treason on the Hudson

During the Revolutionary War, Haverstraw played an important role due to its strategic location on the banks of the Hudson, but achieved notoriety as the site of one of the most treacherous acts in American history. General Benedict Arnold, hero of the Battle of Saratoga, had persuaded George Washington to give him command of the fort at West Point, which controlled the entire Hudson River Valley. Washington was unaware that Arnold was involved in treasonous negotiations with the British. On the moonlit night of September 19, 1780, British emissary Major John Andre met up with General Arnold on the shores of Haverstraw, and they traveled together to the Joshua Hett Smith House in West Haverstraw, where Andre negotiated to purchase the plans of West Point. The plot was foiled by Andre’s capture in nearby Tarrytown as he tried to return to British lines. He was hanged soon thereafter. As for Benedict Arnold, he successfully evaded capture, fleeing to the British side, where he was appointed a brigadier general for the remainder of the war.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 931)

Oops! We could not locate your form.