Hit Them Where It Hurts

The Bennett-Lapid government has unleashed Avigdor Lieberman to inflict pain on working chareidi mothers

It was midwinter 2013 when the so-called “Covenant of Brothers” — an unlikely alliance between left-wing Yair Lapid and hawkish Naftali Bennett — blazed a path through Israeli politics. The pact was meant to herald a new era of progress for Israel’s middle-class majority. But the fraternal bond between the two freshmen party leaders was also meant to guarantee that they wouldn’t be left out in the political cold by Bibi Netanyahu.

It wasn’t long before it became clear where the pair’s brotherly love ended. In the coalition negotiations with the Likud–Yisrael Beitenu bloc led by Netanyahu and Avigdor Lieberman, Lapid declared loud and clear: “I won’t sit in government with the chareidim.” And for the next two years, under the tender mercies of Yair Lapid’s economic stewardship, the brothers inflicted financial pain on chareidi men, women, and children that is remembered to this day.

Nine years on, and it seems nothing has changed. United once again under the anti-Netanyahu flag — this time as joint prime ministers, with Avigdor Lieberman as co-conspirator — Bennett and Lapid have unleashed the dogs of anti-chareidi war with a slashing blow to the financial stability of thousands of chareidi families.

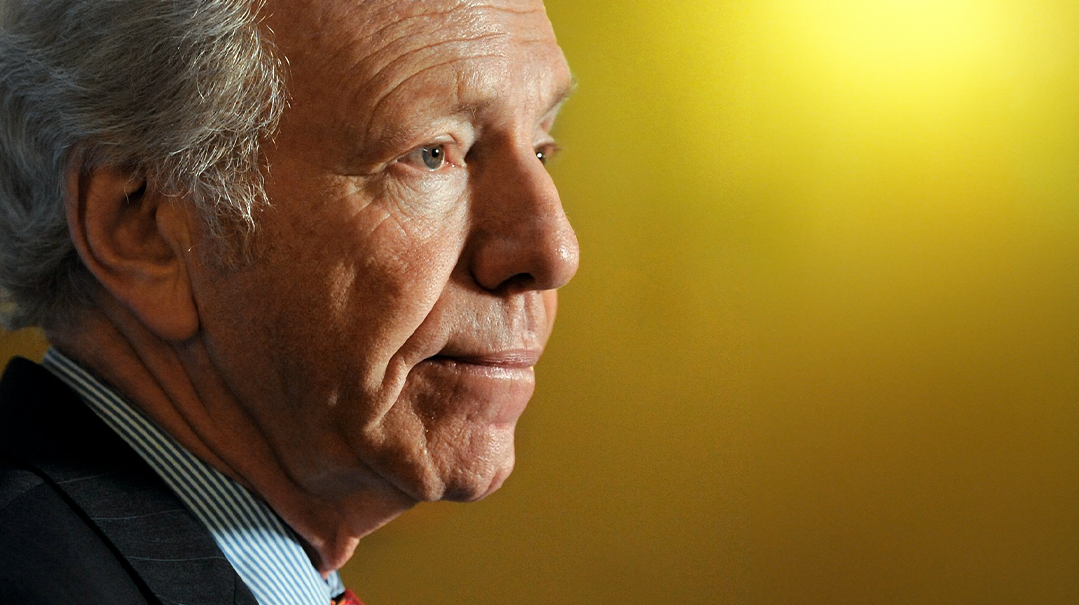

Last week, Finance Minister Avigdor Lieberman and head of the secularist Yisrael Beitenu party announced that beginning September, families in which one spouse was in “non-employment-related studies” — code for kollel — would no longer qualify for government-subsidized child care.

For 18,000 chareidi families, Lieberman’s opening salvo was very bad news. It meant the end of a monthly subsidy worth NIS 1800 per child under the age of three, which in many families applies to more than one child.

Even by current Israeli political standards, the backlash was fierce. “Czar of the Treasury,” MKs from the Shas party labeled Lieberman, playing on the word “Sar” — Hebrew for minister — plus his Russian background and authoritarian approach. Cartoons depicting the Moldovian-born minister starving religious children appeared in the chareidi dailies, reflecting the sense of crisis that the criteria change has thrown many families into. Left-wing MKs such as Meretz’s Mossi Raz said that the policy would affect the poorest families.

“The state has to help those who are struggling, not inflict more challenges,” he said.

For many in the chareidi world in Israel and beyond — and indeed for some traditional Israelis — Torah learning in Eretz Yisrael is the engine room of the Jewish People, and is inviolable.

But even in terms of public policy, the Treasury’s sudden, savage cuts are being challenged as irrational.

“This policy is almost certain to cause a decline in the number of chareidi women in employment,” said the Haredi Center for Public Affairs, a think-tank. “It will also encourage a market in false employment certificates for men so their families can continue to qualify for subsidies, and drive women to use cheaper, un-supervised babysitting options that are less safe for children.”

Underlying the move by the Lapid-Bennett government, says Rabbi Lior Gabbay, head of the Neot Margalit network of child care centers affiliated with the Shas Party, is a patronizing view that chareidi society can be engineered by cutting off funding.

“There’s a drive to pressure the families of avreichim as part of a worldview that sees the father who learns Torah as at the bottom of the food chain.”

Clashes between secular politicians and the chareidi public tend to produce more heat than light, and so the intense media debate surrounding Lieberman’s move has obscured the voices of those affected, leaving generalizations about many thousands of people.

Who in fact are these families, and how much will Lieberman’s cuts affect them? Short of thousands of shekels per year, will they be able to balance their budgets, or will the cuts throw them into serious poverty?

Sudden blow

The Spiegels of Haifa are one family affected by Lieberman’s draconian decision. Both about 30 years old, the husband is a full time kollel avreich, the wife is a draftswoman in an engineering firm, and they have three children. Two are in state-subsidized day care, ages six and 27 months old.

As a country whose welfare system drew heavily on socialist principles, Israel has a long history of encouraging women’s employment through state programs. Part of that broad effort is the maon, government-supervised child care centers where many working mothers leave their children, and it’s that framework that has enabled Mrs Spiegel to work until now. Operating from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m., the maon admits children from about half a year old until three-and-a-half, at which point kindergarten takes over. Children are provided with hot meals and baby formula, and there’s a relatively low ratio of carers to children (about one to six).

In contrast to the maon, which operates six days a week with very few breaks, private babysitters take Fridays off, have a far shorter work day, and take lengthier breaks.

“We still don’t know how Lieberman’s decision will affect us,” says Mrs. Spiegel. “We currently pay NIS 1,846 in total for child care, but if we have to pay the full price, which is NIS 2,857 for a baby and NIS 2,192 for a toddler, we’ll have to pay a total of NIS 5,049 for child care. Given that my salary plus my husband’s kollel stipend (if he even receives it, something that doesn’t always happen) is about NIS 10,000, it’s impossible to live like that. We have a mortgage and three kids to feed, plus utilities and clothing — it’s impossible.”

For the Spiegels, Lieberman’s decision leaves no room for maneuver. Mrs. Spiegel’s job is not one that allows cutting back hours to take over more child care. But she’s pretty sure the decision will boomerang on the Treasury anyway: “There is a chance that if the decision happens, there will be babysitters willing to watch kids until 4 p.m., so we will pay them more than what we pay now, but much less than a full price for a maon. And the state would lose money, because those women will work off the books.”

The scale of those who find themselves in the same boat as the Spiegels, according to the Haredi Institute, is large. “We estimate that it will affect about 20,000 households, including 28,000 children. Since the average monthly wage of a chareidi woman is around NIS 6000, the loss of NIS 1,800 to NIS 3,600 will turn work into an unviable proposition.”

Hitting professionals

The irony of Lieberman’s move is that it targets a subset in the chareidi demographic where at least one spouse is engaged in a profession higher up the economic chain than the traditional Bais Yaakov teacher. By going after chareidim who send children to a full-day child care center, it effectively targets those chareidi women engaged in higher-value professions — precisely the type of employment that a sound economic policy seeks to encourage.

“Since qualifying for government-subsidized child care means working at least 25 hours a week, and it has to be work that justifies the child care payments, effectively this is targeting the women engaged in more lucrative professions,” says Yitzchok Pindrus, an MK for Degel HaTorah.

In addition to the Spiegels, both the Feuers of Beit Shemesh and the Roth family of Beitar Illit illustrate that effect. Mrs. Feuer’s husband is in full-time learning and she holds a professional position at the Beit Shemesh municipality. Over in Beitar, Mrs. Roth supports her family from her wages as a software engineer.

The economics of one professional salary in Israel mean that both families are in the same boat as the Spiegels.

“Our monthly income is less than NIS 8,000, we have a large mortgage to pay, and until now we’ve made ends meet, but we don’t have an extra NIS 1,000 to add,” says Rabbi Feuer. “Lieberman’s cuts will take us from making it through the month to a tzedakah case.”

But it’s not just a matter of extra money. Across the developed world, the trend is for greater state-aided child care, precisely so that working doesn’t become a choice between children’s well-being and wages. The choice now being forced on thousands of families can only end one way, and that is less and lower-quality child care.

“We’ll have to transfer the children to private babysitters who take NIS 1,400 per month to mind the children until 4 p.m.,” says Mrs. Roth, the software engineer from Beitar. “The maon is open six days a week, whereas a babysitter doesn’t work on Fridays. And at the maon the children get baby formula, fruits, and carefully planned meals that contain all the food groups, so I know that if for some reason my child didn’t eat well during supper, he still got all the nutrition he needs.”

The economic effects of the Treasury’s alteration of criteria will be felt further down the food chain as well. Straightforward math shows that for child carers employed at a ratio of about one per five or six children in a population of 28,000, thousands are at risk of losing their income as the maonot close. And that’s no idle threat: in one town in Israel’s south, parents of 110 out of 130 children at the center informed the management this week that they wouldn’t be sending the children back come September.

“No avreichim will leave”

On the political front, Lieberman’s perceived attack on chareidi working mothers has rallied the Opposition, with Likud Party heavyweight Yariv Levin quick to table a Knesset debate about the move. Left-wing MKs from Labour and Meretz have spoken out too, in what they see as a straight defense of women’s rights. Notably silent has been Naftali Bennett, who came in for scathing criticism from chareidi politicians for betraying his promise to represent the interests of the chareidi public.

For the man who joined Lapid in boycotting the chareidi parties in 2013, it’s the second time he’s turned his back on the million-strong sector. But this time, there’s likely no way back for him. In a March pre-election interview with Mishpacha, he blamed the chareidim themselves for driving him into Lapid’s embrace nine years ago, but talked up what he would do for the chareidi public when in power.

Now that Bennett is in the driver’s seat, says Yossi Elituv, an editor at Mishpacha’s Hebrew edition and the author of that interview, responsibility lies at his door. “Bennett and Lapid are responsible for the expected drop in chareidi women’s employment,” he wrote in a widely-circulated tweet. “Lieberman is not a partner, but a man seized by madness and hatred. Responsibility lies with those who could stop the decree and don’t lift a finger — Bennett and Lapid.”

With the Bennett-Lapid coalition in the driver’s seat, what the Treasury hopes is that the arm-twisting will remove the disincentives to chareidi work, opening up a floodgate of men joining the workforce.

That, says Yitzchok Pindrus, won’t happen. “No one committed to learning Torah will make major life changes because of financial pain,” he says. “Besides which there aren’t 18,000 jobs suddenly available. This policy isn’t being driven by economics, but rishus — a hatred of Torah learning.”

The deeply rooted commitment to a life of Torah learning that Pindrus mentions is born out in conversation with the families above.

Asked whether leaving full-time learning was an option for the family, Mrs. Spiegel answered decisively. “No way, not a chance. No and no again. I see it as she’at hashmad, when we fight for Torah in every way possible.”

Mrs. Roth is equally resolute: “My husband will not leave kollel, or bend any laws to get a discount,” she says.

The clash between a government bent on socially engineering the chareidi world, and thousands of equally adamant families, has left those families uncertain about how they’ll manage the impending financial pain.

So while Lieberman may well shift the dial on chareidi employment, it will be in a negative direction, and cause Israel’s chareidi community to batten down the hatches until his term in office passes. But until then, the renewed “covenant” of Bennett and Lapid are doing exactly what they’d promised dozens of times never to repeat: targeting the chareidi world for punitive sanctions.

And meanwhile, as the summer wears on, working mothers face a grim set of choices, Avigdor Lieberman is doing to thousands of chareidi families what he did to the Knesset over the course of four election cycles.

“For myself, our day care director and the babysitters,” says Mrs. Roth, “we’re left hanging.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 869)

Oops! We could not locate your form.