Grand Entrance

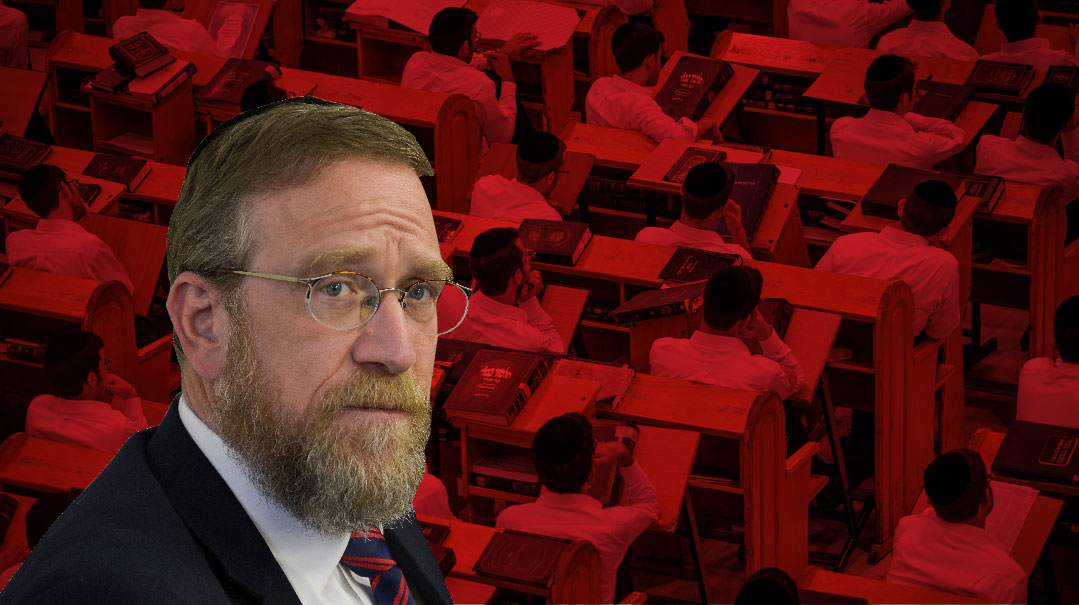

MK Yitzchok Pindrus retraces the battle to bring yeshivah and seminary students to Israel

"The Mir in galus” sounds like a description of the yeshivah’s famous wartime sojourn in Shanghai, complete with grainy photos of bochurim learning in isolation far from home. But under a new framework hammered out last week between Israeli authorities and a broad coalition of 170 Torah institutions catering to overseas students, it will probably describe Elul this year.

After months of uncertainty, the 11th-hour agreement negotiated by Degel HaTorah MK Rabbi Yitzchak Pindrus and Rabbi Nechemiah Malinowitz, director of the Eretz Hakodesh Israel office (the new Orthodox party and big winner in the World Zionist Organization elections earlier this year), gives yeshivah and seminary heads responsibility for their students abiding by the strict “capsule” arrangements that have allowed many Israeli yeshivos to operate even as the country battles a new COVID-19 wave.

Underlying the agreement for the return of foreign students was the formation of a groundbreaking new body representing the full spectrum of Torah institutions, called the Vaad Hayeshivos Libnei Chul, headed by Rabbi Malinowitz and Rabbi Zecharya Greenwald, dean of the Meohr Bais Yaakov seminary.

“On a Zoom call with the roshei yeshivah, we realized that we needed to show the authorities that we were taking responsibility for the bochurim,” says Rabbi Pindrus. “We needed to have a professional plan to adopt the same model that has worked for Israeli yeshivos.”

Creating a common front for the spectrum of institutions, from Modern Orthodox to chareidi, is a notable achievement in itself. But the political backstory shared by Pindrus also reveals the precarious environment in which the Israeli Torah world is currently operating.

Yet together with the relief felt by the nearly 13,000 students who will be allowed to enter Israel for the Elul zeman, the same concerns raised over the Israeli capsule system will apply to the new arrivals.

While the Mir is preparing to house hundreds of bochurim far from its sprawling Beis Yisrael campus, other institutions will be able to implement capsule conditions in their own dormitories. And while there will be plenty of focused, high-quality Torah learning, freely touring the country, spending time in Geula, and even visiting family and friends, will be much more difficult.

For the thousands of talmidim due to arrive in a few short weeks, the new framework means that this will be a yeshivah year like no other.

Political hardball

“The backstory to this agreement began on June 1, when Interior Minister and Shas Party leader Rabbi Aryeh Deri agreed that bochurim could enter the country if they signed that they would go into quarantine,” says Degel HaTorah’s Yitzchak Pindrus. “Talmidim started to come, but then it emerged that some groups were ignoring quarantine rules and not wearing face masks. Deri picked up the phone to various institution heads who told him that they couldn’t take responsibility for enforcing the rules, and so on June 3, he banned any more entries for unmarried students.”

That sudden reversal, as was widely reported, stranded many students who were preparing to fly from the US. It also signaled Deri’s reluctance to take responsibility for foreign yeshivah students — an issue on which he was politically vulnerable as a chareidi minister, and with little incentive to champion.

But the Interior Ministry’s green light to the entry of university students and those on government-funded Masa programs a short time later, provided another angle of attack. “It was actually Ohr Somayach that first alerted me to what was happening, because they had both Masa and non-Masa students,” says Pindrus. “How could some be allowed to come in and others not? We were also able to say to Masa that not only have you cut Jewish-studies funding, you’re also not providing entry visas.”

With the clock ticking and roshei yeshivah trying every avenue to get a hearing, Pindrus played hardball: He called in the Interior Ministry to a hearing in the Knesset for discrimination against yeshivah students. It was a step that didn’t endear him to the Shas Party leadership, but it created a sense of pressure to find a solution.

That was augmented by the creation of the yeshivah and seminary Vaad. “When we were negotiating on behalf of the Eretz HaKodesh party with Masa to restore funding cuts to Jewish-studies programs a few weeks ago, I asked Slabodka Rosh Yeshivah Rav Moshe Hillel Hirsch whether we should be trying to bring in talmidim this year given the health situation,” says Rabbi Nechemiah Malinowitz. “He said that if we could guarantee that things could be done safely, then it should be done, because the year in Eretz Yisrael is so important for the growth of many of them. But he added that we have to create a coalition of everyone from Modern Orthodox to chareidi, yeshivish and chassidish — a non-political coalition of anyone with a Torah-learning program.”

Within a few days, an unprecedented broad coalition of 170 institutions representing around 13,000 students was a reality. “Rabbi Zecharya Greenwald was instrumental in bringing together the seminaries, and we created a Vaad chaired by roshei yeshivah and seminary heads of all streams of Klal Yisrael,” says Rabbi Malinowitz. “When we met Professor Shlomo Mor-Yosef, director-general of the Immigration Authority, he was blown away by the achdus. He said that if we can make one set of rules he would push for it to go through.”

Pindrus admits that when Rabbi Malinowitz asked him to meet with the yeshivah heads, he didn’t want to. “I didn’t think it would help,” he says, “because the problem was a terrified minister, and unity among institutions wouldn’t achieve anything. But as we talked through the issue on Zoom, we figured out that Deri was afraid because no one was taking responsibility. So we thought that we’d need to use the Vaad to create a framework in which yeshivah and seminary heads would take responsibility for their students by following something similar to the successful Israeli capsule model.”

Turning to Shmuel Litov, CEO of the Bnei Brak municipality and originator of the “capsule” model for yeshivos, in which institutions are divided into smaller insulated units to limit the potential spread of COVID-19, a similar framework was agreed upon for foreign students. With the trust fostered by the ongoing success of the capsule system in Israeli institutions, the Health Ministry and the National Security Council — the two bodies tasked with leading Israel’s fight with coronavirus — were able to sign off on the plan.

That left the Interior Ministry, which controls Israel’s borders. “Degel HaTorah head Rabbi Moshe Gafni turned to me and said that it’s not done to call another chareidi MK to a Knesset hearing,” says Pindrus. “But at the same time he told Aryeh Deri, ‘ignore my wild kid, you need to find a solution.’ The political pressure together with the professional plan allowed this thing to go forward.”

Not a Prison

For an idea of how different Elul zeman will look at yeshivos and seminaries that are used to serving as a base for students to explore the country, just go to any of the dozens of Israeli institutions already following these guidelines.

Chevron Yeshivah, for example, has pioneered one model with a thousand students in almost total isolation behind fences, preventing a single case of COVID-19. The media has long tired of recording the once-novel scenes of parents coming to the gates to catch a weekly glimpse of their children. Israeli yeshivah bochurim, accustomed to frequent home visits, have had to get used to the new norm of either in or out.

Another is the now-famous “capsule” system, which allows some degree of movement in and out of the campus, although at greater risk of infection and disruption to the yeshivah. But while some details of the plan as it applies to foreign arrivals are still being negotiated, the overall framework is similar.

“A capsule is a bubble of 26 students who are considered to be a ‘family,’ ” explains Rabbi Malinowitz. “They learn in a partitioned area of the beis medrash, eat together, and sleep in the same dorms. If schools will follow the Chevron model, students won’t be able to go in or out of the campus at all. But if they follow a capsule model, there will be smaller units who will be able to go in and out for certain things which are still being negotiated, defined as “strictly necessary.” But the more freedom you give students in going out, the stricter and more isolated they need to be inside the building.”

Rabbi Zecharya Greenwald, dean of Meohr Bais Yaakov and one of the heads of the Vaad, says that rules seem draconian but are actually flexible enough to provide the girls room to grow. “The first two weeks of quarantine will be a challenge,” he says, “but afterward we’ll probably combine the capsules into one large group so that the girls can get to know each other — but that will also mean that they won’t be able to leave campus for the balance of Elul. We have a nice garden and a gym, and it will be a very warm time together. We’ll probably then go into separate capsules for the winter.”

With regulations a moving target, schools are using their creativity to plan trips and Shabbatons away, and possible Yamim Noraim minyanim on campus within the framework of the capsules. “The fact that we’ve not had a single cancellation from our Shanah Alef program connected to these new regulations shows that the students are serious about what it means despite the challenges,” says Rabbi Greenwald.

But he adds that this very uncertainty is another reason why it’s right to begin on time, and not delay opening, as some have advised. “The Immigration Authority’s Professor Mor-Yosef told me that no one can predict what will be after Succos, and that there’s no guarantee that these entry permits will be available then.”

Staying Safe

What tipped the balance in the negotiations was convincing the authorities that the institutions were ready to police themselves in a serious way. “Our Vaad coalition has signed that we will fund inspectors of our own, to check out institutions and make sure that they’re following the rules,” says Rabbi Malinowitz. “We’re not trying just to convince the government — we’re actively trying to keep people safe. That means that we are not prepared to accept certain groups who’ve flouted the rules so far, and they won’t be able to bring students in.”

“Over the course of the summer, we’ve had 10,000 Israeli bochurim in capsules, a model that has been a resounding success,” says Shmuel Litov, who was a leader in the creation of the framework. “The main difference between Israeli capsules and this model is that foreign yeshivah students must do two weeks quarantine before they begin the capsule, since they are coming from outside the country. And as soon as the ministers saw that there was a serious body taking responsibility for implementing the rules with foreign students, they gave the go-ahead. Credit is due to Aryeh Deri for fighting the Health Ministry’s demand that the new arrivals must quarantine as individuals, which is impossible in a dormitory setting.

“The capsules,” he adds, “are a lot of work, but they’re not a prison.”

The multiple government bodies who had to be convinced that the plan was workable didn’t see the foreign yeshivah sector as a particularly high priority, despite the dollars that it generates. “Even the Finance Ministry wasn’t impressed by the money. They said, ‘you bring in $400 million, but the tourism industry brings in billions — and we’ve shut the whole thing down,’ ” explains Yitzchak Pindrus.

Alter Mirrers

Coronavirus has dramatically impacted all yeshivos, but perhaps none more so than the powerhouse that is Mir. On a recent visit to my former chaburah there, I saw the normally packed batei medrash far below capacity, the decibel level noticeably lower, the stores around the Beis Yisrael neighborhood shuttered, and too many available parking spaces around the yeshivah.

Under the new plan, the crowds won’t be returning anytime soon. While avreichim will continue to learn in the socially distanced, mask-wearing beis medrash, hundreds of bochurim will find themselves in capsules far from Jerusalem.

“We don’t know exactly how many talmidim will come back, but normally we would have 1,700 foreign bachurim, and we’re now preparing for 500 to return,” a source in the yeshivah says. “There’s no possibility of doing capsules in Beis Yisrael, so we’re looking at different campus options outside of the city.”

Those weighing coming to Israel now will have to consider the difficulties inherent in the capsule system. While it has enabled thousands to go on learning — possibly even more intensively, given the lack of distraction — the streets and shuls of chareidi neighborhoods around Israel are full of those who haven’t joined the system. Large numbers of otherwise “good bochurim” are deterred from rejoining their yeshivos by the prohibitive “in-or-out” choice that the capsule presents.

What will that mean for those who come to learn in Israel in Elul 5780/2020?

“There won’t be the normal atmosphere of being able to go around Eretz Yisrael, travel to mekomos hakedoshim, or do the regular things that bochurim do. It’s mesirus nefesh to come back to learn like this,” the Mir source adds, “so the fact that hundreds are going to do it is really special — they want authentic learning.”

Time Capsules

In order to qualify to join the yeshivah and seminary Vaad, institutions must agree to the following conditions:

-Students must travel from the airport to their dormitories on private transport, with one driver servicing the group.

-Six students will quarantine together, with access to a separate washroom, in isolation from other groups.

-Anyone testing positive for coronavirus must go into individual quarantine.

-After 10–14 days, schools can choose one of two options:

1) The capsule model. Students enter capsules which are treated as a “family,” meaning that the same group of people learn and eat together. Students can leave to go shopping or to places where there are not significant crowds (so Geula would be off limits) while wearing masks and observing social distancing.

Going away for Shabbos would only be permitted if everyone visits the same family.

Currently up to 26 students are in a capsule, but this is expected to rise to approximately 50.

Staff must enter the campus with masks and distancing.

2) The “Chevron” model. This is more draconian, with the campus almost entirely sealed off, to ensure zero infections.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 821)

Oops! We could not locate your form.