Gimmel-Dalet

| January 3, 2023Receiving gracefully is an art — and in doing so, you become a giver

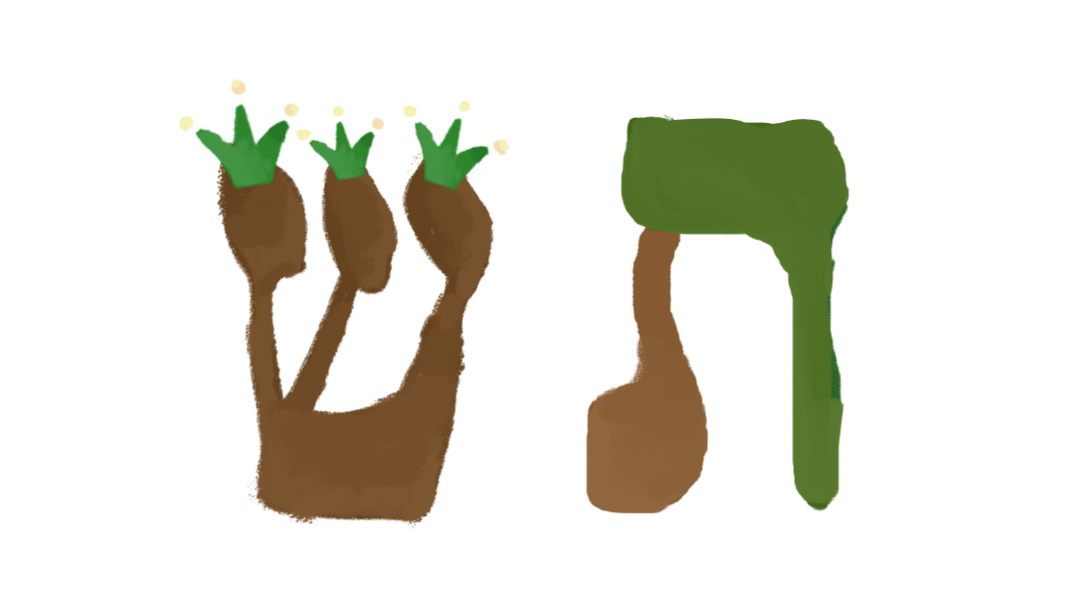

Gimmel

Name: Gimmel from the word gomel, meaning to give

Gematria: Three

Shape: Looks like a person — has a head, a back, and two legs

Middah: Giving

Alef represents the Source of all, and beis signifies the creation of this world. Gimmel is the next step in the process. It’s about turning potential into action.

The root gimmel-mem-lamed can spell gomel — to give. A core purpose of man’s existence is to emulate Hashem in being a selfless provider. For this reason, the gimmel is in the shape of a human being (Shabbos 104a).

We see the same root in gamal, a camel. Camels have incredible endurance; they can go for long periods of time, sustaining themselves through a harsh desert — once they fill themselves up, that is (Rav Shimshon Raphael Hirsch, Bereishis 21:8).

If we want to be givers, we need to nourish ourselves first. Once we’ve developed our own resources, then we can support people through their own challenge-filled deserts. We can be gemalim who are gomlim.

Looking at the shape of the gimmel, one part splits off into two, just like an act of giving, which branches out endlessly. Think of how many organizations and movements were started with a seed planted by one person!

Giving doesn’t only have to effect massive change in society. My bright smile to a friend can make that woman a happier mom, her children happier kids, their friends happier people… We can’t underestimate the potential of one little act.

From a different angle, we see that the two legs at the bottom of a gimmel combine to create one. Huge corporations are the fusion of many talented individuals. According to the Maharal (Tiferes Yisrael 18), the number three, which is the gematria of gimmel, is the number of integration. This world is a place where two opposing forces, G-dliness and physicality, converge into one reality. Three creates flexibility. When my idea is at odds with yours, we’re stuck. But maybe there’s a way to compromise? Maybe there’s a third creative option we didn’t yet discover that integrates both perspectives?

We learn in Koheles (4:12) “Chut hameshulash lo bimheirah yinatek — a cord of three strands will not easily break.” Shlomo Hamelech is saying that three is also the number of stability. Three legs are the minimum required to keep a table standing. The mishnah in Pirkei Avos (1:2) tells us that the world stands on three things: Torah, avodah, and gemilus chasadim.

Our nation stems from the three Avos, who each embody a particular middah. Avraham Avinu is the epitome of chesed. This parallels the gemilus chasadim referenced in the above mishnah.

Yitzchak Avinu embodies gevurah — strength. It takes strength to have self-control, to set boundaries, to stand up for what you believe in. This is the avodah Pirkei Avos refers to. What’s the connection between gevurah and avodah? Generally, avodah refers to korbanos, or our substitute today — tefillah. Both of these take discipline to perform properly.

The traits of chesed and gevurah are contradictory. If you keep giving, you may become depleted. If you’re constantly setting boundaries and acting stringently, how can you be kind?

Yaakov Avinu is the embodiment of the middah of emes (which is parallel to Torah in the mishnah). Torah is emes — it’s not weighted toward chesed or gevurah; it’s the beautiful synthesis of the two. For this reason, emes is also known as tiferes, beauty. What’s beautiful is what’s perfectly symmetrical. When we can look at a situation with a true Torah perspective, we can see whether it requires a chesed- or gevurah-type response.

Gimmel also shares a root with the word gomel, to wean. The highest level of tzedakah is to help a person become self-sufficient, to be able to stand on his own, to wean him off of the need for help. This alone requires the setting of boundaries, placing a limit upon the chesed we do so that it’s the greatest form of giving.

Dalet

Name: Dal - poor / downtrodden

Deles - doorway

Shape of the Letter: A man who is bent over, or a doorway with one side missing

Gematria: Four

Middah: Receiving

Most people in modern society don’t aim to be “takers.” It’s considered a maalah to be independent. But we’re never truly self-sufficient. There’s always a vertical direction of acceptance — of receiving gifts from Hashem. The Gemara (Shabbos 104a) explains that the foot of the dalet reaches back toward the gimmel because we all need to be able to receive.

The “doorway” of the dalet represents the passage of giving and receiving, of connection. When you’re in need, I open my door to help you. When I’m the one in need, you open yours. This doorway has only two parts showing, because there’s an open and obvious aspect to the flow of giving, but there’s a hidden one as well. I go for a lonely walk late at night, wishing I had a companion. Along the way, a stranger asks me for directions. Instead of just pointing out the right route, I walk my new friend all the way to her destination. She thanks me, and I thank her. Who is the giver and who is the receiver? It’s unclear — all are contained in the hidden and revealed aspects of the dalet.

The number four often relates to foundational aspects of the world: the four directions, the four basic elements (earth, air, fire, and water), and the four rivers of Gan Eden that flowed out to create the rest of the world. There were four Imahos and four mothers of the Shevatim. This tells us that the middah of four, of the dalet, of receiving, was built into the very fabric of creation. Hashem gives to us and we receive. We give to others and they receive.

In that vein, we need to learn to receive in a horizontal direction as well — from our peers. The aim is not to be takers, looking to get as much as we can out of others, but rather to be receivers — to recognize that we’re actually dependent upon the help of others. We’re all “dal” — poor — in some way.

Rav Dessler (Michtav MeEliyahu, Kuntrus Hachesed) describes a kind of giving that can actually be taking, when we give for selfish reasons. And there is a kind of taking that is actually giving, because one takes so that another can give. It’s an art to receive gracefully, and in doing so, to actually become a giver.

Gimmel and Dalet Together

Gimmel is the gomel, the giver. Dalet is the poor one in need. The foot of the gimmel reaches out to the dalet, to give to it. A tiny piece of the dalet sticks out of the “doorway” on top. People don’t always indicate that they’re in need, but as givers, we can still be attuned to the hints.

At the same time, we can’t enter the doorway without knocking. People don’t want to feel they’re your chesed case. For this reason, the dalet faces away from the gimmel (Shabbos 104a). A creative gimmel finds ways to help that preserve the dignity of the dalet by giving secretly, subtly, or even giving the taker an opportunity to be a giver herself.

Mindel Kassorla is a teacher, graphic designer, shadchan, and Mishpacha contributor. Her older sister, Cindy Landesman, is the head mechaneches of Shearim Torah High School for girls in Phoenix, AZ and the director of its Shaarei Bina adult women's education program.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 825)

Oops! We could not locate your form.