Deri’s Day in Court

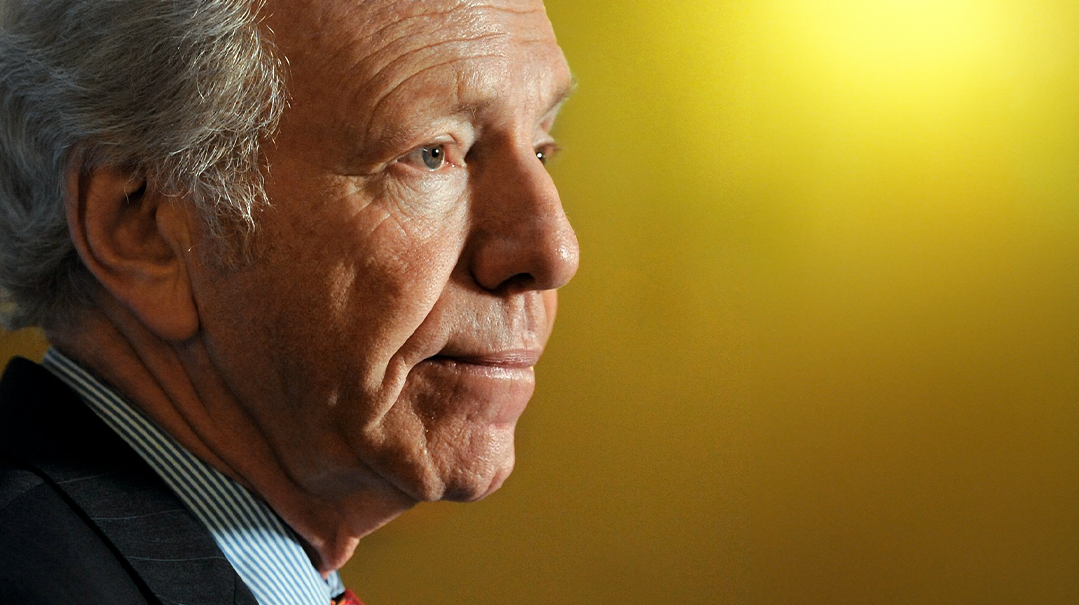

As the efforts to cut the courts down to size get underway, is this the last of Minister Aryeh Deri?

Photos: Flash90

The High-Court’s move to ban Aryeh Deri from ministerial office has opened up a new front in the seething feud between Israel’s right wing and the justice system. But as the efforts to cut the courts down to size get underway, is this the last of Minister Deri?

Judges Hit Back

By Avi Blum Esq.

1.

Twenty-four years ago it was Rav Ovadiah Yosef who rushed to Aryeh Deri’s house after a High Court ruling against the Shas movement’s founder, famously crying, “By law he’s innocent.”

This time it was Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu who showed up at Deri’s house for an extended talk after the High Court ruled that the Shas leader must leave the government.

“When my brother’s in trouble, I’m there,” Netanyahu said.

As the most seasoned politician in the country, Bibi was looking after himself as much as his brother.

In 1999, Deri was at the height of his career, having led Shas to a record 17 seats. Deri was at the gates of the promised land, but was denied entrance after a conviction in his trial sent him behind bars.

Twenty-four years later, Deri is back. Under his leadership, Shas garnered 400,000 votes at the last election and scored a double-digit number of seats for the first time since Rav Ovadiah’s passing. The right-wing bloc he nursed almost singlehandedly through a year and a half in the opposition won a stunning victory, making Deri the strongest man in the government after Netanyahu.

And that’s just where history repeated itself. Having been burned in his thirties, Deri wasn’t eager to relive the experience in his sixties. Last year, as a rank-and-file MK, Deri ended six years of investigations by signing a plea deal to avoid the drawn-out agony of another indictment, trial, and conviction. But by the end, the only charge remaining from a slew of grave accusations, including bribery and breach of trust, was a tax offense. As then attorney general Avichai Mandelblit put it, “The proverbial mountain didn’t even give birth to a mouse.”

Only one thing was left unsettled in Deri’s plea deal, which saw him receive a suspended prison sentence and resigning from the Knesset in exchange for the charges being dropped — “moral turpitude,” a vaguely defined legal concept that can be imposed on a convict by the Court or the chairman of the Central Elections Committee. In the out-of-court compromise between Deri’s legal counsel and state prosecutors, the two parties decided to push off a decision on the matter until Deri was up for a ministerial appointment.

But that moment came earlier than expected, with the change government’s premature collapse and the formation of a fully right-wing government with Deri at its center. Appeals against Deri’s appointment as interior and health minister were not long in coming. To Deri’s luck, Justice Minister Yariv Levin chose to announce the launch of a judicial revolution aiming to uproot the High Court’s power just before it heard the appeals against Deri’s appointment. Deri found himself a pawn in a much wider struggle.

2.

Ahead of the government’s swearing in, the coalition amended the Basic Law to enable Deri to serve as minister despite having received a suspended prison sentence as part of his plea deal last year. This clearly signaled their intention to circumvent any High Court ruling disqualifying Deri from joining the government. In retrospect, this was a mistake, giving the High Court two weeks to work on making its ruling on Deri’s appointment virtually unassailable.

The High Court’s 10-1 ruling disqualifying Deri was based on two key legal doctrines. The first legal doctrine cited in the ruling was that of “reasonability.” High Court President Esther Chayut, now leading the resistance against the government’s judicial reform agenda in her last year on the job, cited Deri’s history to establish that under the circumstances, his appointment as minister borders on “unreasonable in the extreme.”

But the High Court justices did their homework, appending another argument to their ruling. They quoted Deri’s words at his plea deal hearing to argue that he had misled the court at the time by suggesting he intended to retire from political life altogether. The doctrine of juridical estoppel prevents a defendant from pleading two contradictory arguments in different cases and winning both of them. Without going too deeply into the ins and outs of the legal system, the multilayered ruling is akin to locking the door and swallowing the key.

Attorney Michael Ravillo, Netanyahu’s legal counsel during the political negotiations, gave his opinion that all the options discussed ahead of time for circumventing the High Court’s ruling have been rendered moot. The coalition’s prior plan of action — eliminating the reasonability doctrine — won’t be enough in light of the additional arguments cited in the ruling.

Another option being floated is for Deri to be appointed alternate prime minister in the same framework as the Netanyahu-Gantz and Bennett-Lapid governments, except that this time, Deri would only serve as prime minister for one month at the end of the term. But even that option, which would require the government to dissolve itself and be sworn in anew, won’t necessarily stand the test of the High Court. Prime ministers are better protected than ministers against the legal system, which is why Netanyahu is able to serve despite the standing indictments against him, but the arguments the justices cited could be enough to disqualify Deri from serving as alternate prime minister, as well.

Deri refuses to give up. Another trial balloon being floated is legislation that would make political appointments immune from judicial oversight. But Deri also understands that in the new reality, any plan to bring him back to the government table will take many weeks and could still fail the test of the High Court, which is sure to strike again after whatever legislation the coalition passes.

Before Netanyahu could formally fire Deri at the government meeting on Sunday, Attorney General Gali Baharav-Miara sent Netanyahu a letter ordering him to dismiss Deri while adding a swipe at Netanyahu, pointing out that he can’t hold Deri’s portfolios either as he’s also under indictment. It seems like the legal system did everything in its power to cut off every avenue for Deri’s return to the government table.

3.

The High Court justices sent two messages with one ruling. The first message was aimed at Justice Minister Yariv Levin and his ally Simcha Rothman, chair of the Constitution, Law, and Justice Committee, who would like to go ever further than Levin has. That message could be summed up as: We’re right here — do your worst.

The second message was directed at the Israeli public. Before the ruling, Levin was defining the parameters of the struggle, outlining one case after another in which the High Court overreached its authority — but now the justices could demonstrate concretely to the public what they were fighting for. They took abstract principles such as the reasonableness doctrine and concretized them in the Deri case, fully conscious that a broad swath of the Israeli public would sympathize with the principle of keeping a convict away from the government table.

It’s no accident that the coalition leaders’ first decision after the ruling was to try to distinguish between Deri’s woes and the judicial reform plan. To judge by the media and public reaction, that attempt has been a resounding failure.

At the same time, the High Court justices have made a powerful enemy. Deri has no intention of retiring from the scene, and even if he doesn’t return to the government table, he’ll remain the dominant leader of a political party controlling 11 seats in the Knesset. Deri has already been in this situation before, having remained outside the cabinet during Netanyahu’s first government in 1996 due to the standing indictments against him at the time.

In legal terms, the court’s decision by a panel of 11 judges is a last word from which there’s no appeal. Once the High Court justice has risen from his seat, there’s no one else to appeal to. But this game, as political as it is legal, is still in the opening phase. Levin fired the opening salvo, the High Court responded with a bombardment of its own, and now the heavy guns will start roaring.

Shas's partnership with the left in the 1990s gave way to a firm embrace of Bibi and the right

Court of Public Opinion

By Gedalia Guttentag

“B

elieve nothing you read and only half of what you see,” is a piece of sage advice dispensed by Edgar Allen Poe that comes to mind when thinking about the ever-shifting sands and desert mirages of Israeli politics where things are rarely as they seem at first sight.

That’s doubly true of the High Court’s show-stopping decision last week to bar Shas founder Aryeh Deri from holding office as a government minister.

To Deri’s political opponents on the left, the case is open-and-shut: As part of a plea bargain to drop tax charges against him, the political veteran had told a court six months ago that he was retiring from public life.

The fact that 400,000 voters subsequently voted for him was immaterial — Israel’s highest court had spoken, and Deri had no place in Israel’s top decision-making forum any more.

The view on the right side of the political map is that the Court’s decision was not a legal ruling taken in a vacuum, but part of a wider political game. With the preeminence of the High Court threatened by legislation from Netanyahu’s coalition, the ruling was a shot across the bows warning the government not to touch the country’s judicial status quo.

With the Deri saga set to bedevil the latest Netanyahu government, understanding the underlying issues is crucial to following the next steps in Israel’s politics. Here are five takeaways.

Accompanies by a crowd convinced that the justice system had attempted to bring Shas down, Deri enters Ma'asiyahu prison in September 2000

Politicized Court

The key to understanding the Deri ruling, charges Nissim Ze’ev, who founded the Shas party back in 1982 and served as an MK for many years, is that the Court was acting in a political sense, not a judicial one.

“The High Court lost its credibility long ago,” he says. “It’s politicized and dominated by left-wing values. For example, in my time in the Knesset, an MK from the Balad Arab nationalist party, Azmi Bishara, was suspected of undermining Israel’s security. The Shabak testified to the court to that effect — charges that were indeed later proven when Bishara fled the country — but the Court ruled in his favor.

“The same was true regarding demolishing terrorists’ houses: the High Court intervened again and again against the policy.

“The Court overturned the Knesset’s law limiting illegal migration three times. The same for the recent move to allow chometz in hospitals on Pesach. It’s clear that the Court has an ideology which is left-wing and anti-halachah.”

Identity Wars

In the clash between two competing versions of Israel — one secular and liberal, the other traditional and Jewish — the court comes down on the secular side.

“Deri was caught in the crossfire over the battle for the country’s identity,” says Ze’ev, “because reforming the justice system as this government wants to do will end the attacks on halachah and the undermining of Jewish security that the Court enables. So, he paid the price — it was clear that the Court was going to rule against him, because he is a linchpin of Bibi’s government.”

The idea that in the Deri ruling the Court acted with more than the dry legal facts in mind is widely accepted across Israel’s right.

Amit Segal, a high-profile political analyst, tweeted that “what the last few weeks prove is the absolute control that one sector has in all the real centers of power in the country, with the exception of the Knesset. In such a situation, the question of who is in power is almost irrelevant. He will be washed away, and the agenda will be set by others.”

Crime and Punishment

Central to the right-wing case is the fact that unlike in 1999 when he was imprisoned for corruption, this time around Deri’s crime was a minor infraction, by any account.

When police investigations of Deri’s business dealings were announced back in 2015, they were for major crimes of corruption. But after an unprecedented seven-years-long investigation, the results were embarrassingly meager.

Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit expressed his disbelief at the judicial hounding that the justice system had subjected Deri to, saying that “the mountain didn’t even give birth to a mouse.”

“If the Justice Ministry thought that there was a chance of convicting Deri, would they have let him get away with a plea bargain?” asks Nissim Ze’ev.

“It was simply to save the system from embarrassment that they wanted to prevent this from going to court.”

Smoking Gun

For evidence that the Deri decision was about deterring the government’s moves against the Court itself, many on the right point to the convenient timing of the ruling.

Aryeh Deri’s continued involvement in public life was a fact the day after his plea bargain was signed. He carried on as head of the Shas party, entering the Knesset plenum as an advisor. That was well-known, and yet the Movement for Quality Government in Israel, a left-wing NGO that is a sworn foe of Deri’s, only brought the case to the High Court after Bibi’s return to power.

The reason, Deri’s supporters say, is clear. Until Bibi’s victory — masterminded by Deri himself — left-wing parties still hoped that Deri would abandon Bibi and form a government with the left.

While that, to Deri himself, was delusional, it was the main policy platform of Benny Gantz, one of the opposition heads.

Had Deri joined a left-wing coalition, his advocates say, there is no way the case would have been brought to court; and if it had, the result would have been in Deri’s favor.

"Bibi needs a strong Aryeh" remained the theme of Shas's campaign for five long election cycles

Bibi’s Brain

The judicial blow came as Deri basked in the triumph of Bibi’s return to power. Deri’s decision at the beginning of the cycle of back-to-back elections to hug Bibi and the Likud tight paid off as Deri became the acknowledged elder in the room of the Bibi bloc, responsible for holding it together during the year-and-a-half of exile in opposition.

From a nadir of seven seats in the 2015 election, when Shas was widely eulogized for its descent from national prominence to the status of Sephardi chareidi party, Deri rebuilt Shas into a cross-sectoral force, uniting traditional Sephardi Jews — many of whom had drifted to Likud over the years.

To have rebuilt from the ashes and then lose his seat at the top political table leaves a bitter taste — one that was obvious on Deri’s face in the wake of the High Court ruling.

Puppet Master

Where does Aryeh Deri go from here? While it’s clear that he would like to find a legal route back to the top by way of government legislation, he’ll remain a top player even from the Shas offices in Jerusalem’s Har Hotzvim business park.

Yossi Elituv, editor of Mishpacha’s Hebrew edition and a longtime observer of both Deri and Shas, says that Deri is in an unrivaled position of strength despite the blow from the Court.

“If someone had said to him back in 2015 that he would be able to close the legal investigations against him and retire from the Knesset while being the de facto prime minister, he would have grabbed the deal with both hands.

“With Bibi in need of his 11 seats — essentially captive to him — and Shas in unprecedented power with key ministries in hand, he’s in that position.”

Deri, says Elituv, isn’t going anywhere. “He has no political rivals within Shas. He is the only one who can manage the movement, and he will continue to do so from outside the Knesset.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 946)

Oops! We could not locate your form.