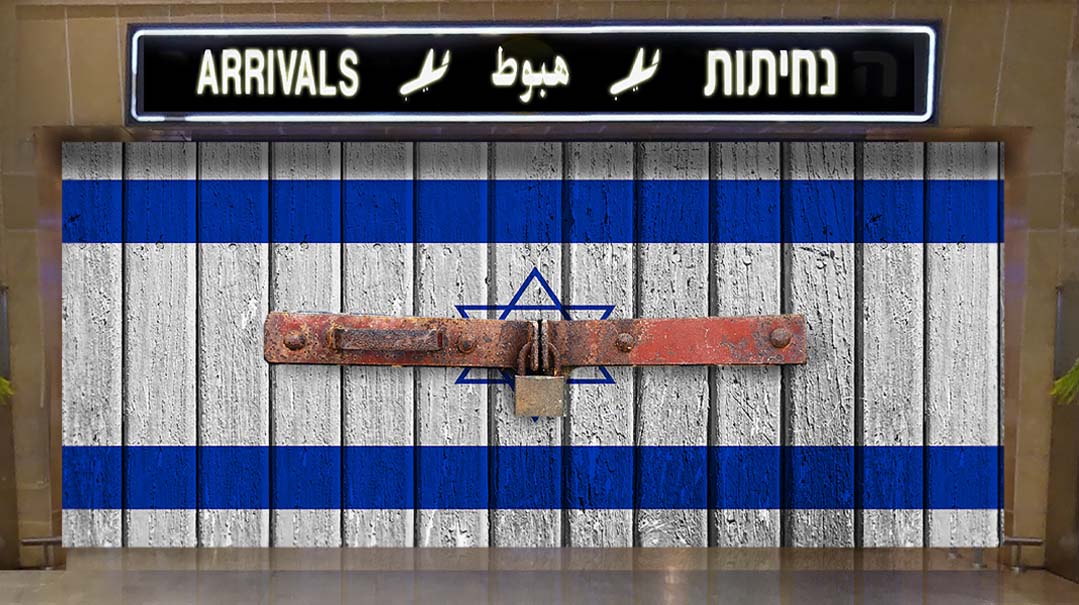

Closed Borders, Closed Ears

Why is Israel ignoring the pleas of Jews cut off from their families?

With reporting by Ariella Schiller and Eliezer Shulman

Almost two years after becoming the first state to wall itself off from the world as Covid burst out of China, Israel is once again the country that dwells alone.

“The Omicron strain is here, doubling infections every two to three days, and the fifth wave has begun,” warned Naftali Bennett in a Sunday night press conference, urging masks, social distancing and a vaccine booster campaign on a weary public.

For tens of thousands of families both in Israel and worldwide for whom Covid has normalized a once-unthinkable separation from friends and loved ones, the die was cast a day later. Ministers added a slew of Western countries including Belgium, Canada — and for the first time since the onset of the pandemic, the United States — to a no-travel “red” list that already featured England and France.

But as Israel walls itself off from almost the entire Jewish Diaspora, a mix of anger and despair at the latest draconian travel ban is growing among the hundreds of thousands of people affected. From Jerusalem’s English-speaking chareidi community to French olim, lone soldiers, and secular immigrants up and down the country — all suffering from family absent at special occasions or the sight of grandparents — the same refrain is heard.

“Of course, Israel needs to take precautions because of Covid, but what’s going on here is a chutzpah,” says former Shas MK Yossi Tayb. “I get dozens of calls a day from people who have been turned away from the Exceptions Committee with no reason given. A man whose daughter had a first child after 12 years applied to come from America and was refused. A family whose son is getting married was turned away with the same answer: ‘You don’t fulfill the criteria.’ There’s no one to talk to.”

Every previous round of entry restrictions stirred resentment and debate about the balance of public health measures and normal life. But as the Omicron variant spreads with alarming speed across Israel’s population, it’s not just the health policies that are under fire, but the oblivion to olim’s needs that seems to underpin it.

“This is a country of immigrants,” says Michal Cotler-Wunsh, who served as an MK for the Blue and White party in the last Knesset. “We left everything behind on the assumption that we are just a flight away from our families. So two years into Covid, entry for first-degree relatives should not be on a humanitarian case-by-case basis, but rather should be recognized and prioritized as the rule, subject to public health requirements.”

And for Rabbi Nechemya Malinowitz, co-founder of the Igud, a body formed to represent foreign yeshivah and seminary students in Israel, the emphasis on citizens doesn’t take into account Israel’s unique place in global Jewry.

“Every single Jew has a connection to this land,” he says. “It can be immediate — their married children live here, their spouse is buried here, they’ve been coming every January for the past 30 years. And for others, the connection is a spiritual one. Either way, that’s the key factor the government is missing. They’re creating policy as if Israel is just another country.”

Where’s the Logic?

When former prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu first enacted a global travel ban in March 2020, the yeshivah and seminary year became a flashpoint issue.

“When I heard that they would not be letting seminary and yeshivah students into Israel, but that MASA programs would be allowed in, I knew I had to do something,” says Rabbi Malinowitz, who’s also the director of Eretz Hakodesh, a chareidi slate in the World Zionist Organization. “I reached out to then–interior minister Aryeh Deri and he responded that they couldn’t deal with the yeshivos and seminaries because there was no one taking responsibility for their Covid policies. So I approached Rabbi Zecharia Greenwald, principal of Meohr seminary, and we created Igud Hayeshivos. Every single seminary and yeshivah program in Israel — from Modern Orthodox to chassidic and litvish — is under Igud Hayeshivos.”

In a story that was covered extensively in these pages at the time, the creation of the Igud enabled the entry of 16,000 students last year, and the original impetus remains true for the current wave of restrictions.

“We can’t have our students shut out of Eretz Yisrael,” Rabbi Malinowitz says. “This year will never happen again. This isn’t a vacation that can be postponed until ‘things calm down.’ This is these students’ year to grow, to learn, to find themselves.”

If the student population was the most visible group of those locked out the country, families were an immediate casualty of the closures.

“You can’t imagine the number of calls we received from families split up,” says Rabbi Paysach Freedman, CEO of Chaim V’Chessed, which advocates for English speakers in Israel. “Husbands who went to America for simchahs and couldn’t get back, mothers who were separated from children. It was a nightmare.”

Chaim V’Chessed provides guidance and advocacy at every level of interaction with authorities, from the Interior Ministry to negotiating for special-needs care, and navigating medical bureaucracy. With Israel opening and shutting like an accordion, the share of travel-related questions has ballooned. Of the 4,700 cases opened this year, 2,700 of them involved Covid travel restrictions from student visas to families stuck overseas.

A country has the right to decide who will enter its borders and who won’t, acknowledges Rabbi Freedman, but Israel is different. “The entire Jewish world has a connection with Israel. No one is trying to have their dead buried in France. It’s only here that we’re dealing with allowing meisim in. The government seems to have forgotten this.”

At the root of the problems regarding entry to the country, says Rabbi Freedman, is an often-thoughtless policy-making approach that has terrible real-world consequences.

“Just a month ago, we succeeded in convincing the policy makers that if a baby’s parents are vaccinated and their center of life is in Israel, they should be allowed in. Because before that, if you wanted to leave, your baby had to remain here without you. Does that make any sense? And is it logical that if you’re recovered and the doctor won’t give you a booster, then you can’t come in? There has to be a logic behind the red tape.”

The Exceptions Committee, or “Vaadat Hacharigim” as it’s known in Hebrew, is a case in point. Tasked with reviewing entry and exit requests at different points in the pandemic, it scrutinizes cases classified as humanitarian — such as being by the bedside of a loved one about to pass away, or even attending a family simchah.

“I saw the Exceptions Committee operating,” Rabbi Freedman says. “They were just a group of young people, barely out of their teens. How can they be expect to pore over medical documents and tell someone if they can be by their dying mother’s bedside?”

In the information vacuum that has characterized the pandemic, another go-to source for Americans regarding changing government regulations has been Zvi Gluck, CEO of Amudim, an organization dedicated to helping abuse victims and those suffering from addiction within the Jewish community.

“A government has the right to make rules,” he told Arutz Sheva. “We have to respect those rules. The issue is that certain rules don’t make sense. Why can’t those recovered with monoclonal antibodies be allowed to enter? There has to be criteria that make sense. We do appreciate that for emergencies, the government is bending over backward. But Israel is our home, and we want to be able to visit when we can. We hope they can ease the pain and make it easier for everybody.”

First-degree Pain

In the carousel that is Israel’s ever-changing restrictions, it’s hard for anyone to keep up, as a surprised Health Ministry official discovered in the Knesset this week, when lawmakers struggled with basics of pandemic policy such as quarantine length for those infected with the virus.

But one thing is clear: Israel’s rules have tightened to exclude olim’s first-degree relatives — something that hasn’t been the case since the early days of the pandemic.

“In the 23rd Knesset, I initiated an emergency session in the Absorption Committee to debate whether first-degree relatives — parents and siblings — of citizens should be allowed in,” says former MK Yossi Tayb.

“In the end, committee chairman David Bitan passed the law that for immigrants within ten years of coming to Israel, their relatives could enter. You have to remember that that was even before there was a vaccine. So why with all our vaccines and boosters are they rolling that back?”

At the root of these measures, says Tayb, is a lack of understanding about the nature of aliyah. “The government spends millions encouraging immigration to Israel — we’re meant to be an immigrant country — and then they close the door in your face.

“The government has to understand that for the last decade, people have moved to Israel because of love of the country, but they have alternatives. They’re not fleeing Morocco or the USSR. Many have good lives, and they’re willing to give it up. But now you’re asking them to come, and not to see their families?”

Although she’s no longer a Knesset member, Michal Cotler-Wunsh, an immigrant from Canada, is still an address for dozens of weekly pleas for help with family denied entry to Israel.

At a hearing of the Knesset Law Committee this week, she told MKs about some of the tragic consequences of the border policies. “A recent case was so painful, involving a mother whose three children live in America, while she is in an old-age home here. The children were denied entry to be with her in her final hours, and so she died alone. Yet despite Covid health concerns, the rules permitted them to come days later for her funeral.”

Tragic absurdities like that, says the former lawmaker, are what a blanket entrance permit for first-degree family members would avoid. “I was just involved in a painful case involving non-citizens — parents whose child had been murdered in a terror incident here — and had to fight for their entry to inaugurate their child’s memorial.”

The first-degree policy that the previous government enacted — and was cancelled thereafter — was something that Cotler-Wunsh strongly advocated in her time in the Knesset. It was based on a model she was aware of from back home.

“I’m from Canada, and that country allows everyone who can prove a first-degree relationship with a citizen to enter.

“I believe that in a 73-years-young and miraculous country of olim that values and encourages aliyah as the ultimate realization of its vision, mission, and values, there are considerations that must be factored in as part of decision-making processes in advance, not in retrospect and in individual, reactive, ‘exceptional’ cases. There must be a separate category, with holistic, clear, and transparent policies and consistent implementation. Families of olim are not tourists or exceptions, they are the rule.

“The exceptions that I fought for in the last Knesset,” she continues, “were for families of lone soldiers, of girls doing sherut leumi, of those who gave birth, and so forth. The demand for a holistic approach to first-degree family members, subject to Health Ministry restrictions, are the first step in a paradigm shift I believe is necessary on so many levels when it comes to olim.”

Playing Politics

The irony of this latest total shutdown is that it’s been enacted by Naftali Bennett’s so-called “change government,” which famously declared its opposition to the strict Covid policies of its predecessor, as well as seeking to rebuild the breakdown in Diaspora-Israel relations.

So it’s no surprise that in seeking comment for the abrupt reversals in policy, government representatives proved difficult to pin down. Interior Minister Ayelet Shaked, responsible for borders and immigration, declined to comment.

According to political analyst Shalom Yerushalmi, voices of dissent were raised around the Cabinet table.

“Why are you closing the borders when Omicron is already here?” asked one minister. “Be more logical, make strong entrance requirements. But to send thousands of people who just want to travel to Europe to the Exceptions Committee?”

Whether or not he was the one who used those words, Diaspora Affairs Minister Nachman Shai told Mishpacha that he’d personally voted against the new travel policy — but that the government’s policy was based on the health experts’ decision.

“There are 600,000 Israelis not vaccinated, and 1.2 million who haven’t taken a booster, and this is a terrible disease that could overwhelm our hospitals. We’re trying to bring down to zero the number of people who come in, so that we don’t end up shutting down our economy or schools.”

Asked about the unspoken contract between immigrants and the government, and the possibility of enforcing strict health requirements on visitors, he pushed back. “Who’s disconnected you from your family? This is only a health policy to try to stop Omicron going viral, and it probably won’t last long because it’s too late.”

Based on her comments, another dissenter was likely Absorption Minister Pninah Tamano-Shata. According to her spokesman, the minister had pushed both in this government and the previous one for first-degree relatives’ entry permits.

“That’s due to an understanding of the need to maintain public health, yet also understanding the difficult place in which Israeli citizens, and specifically olim, are away from their families and support networks during the most important and significant moments, and in order to ensure that aliyah does not stop at any point in spite of the global pandemic.”

Israel’s political divide has also played a part in the new entry difficulties, says Yossi Tayb. “When Shas headed the Interior Ministry, I could talk to the ministry’s CEO, to help smooth out difficulties. Now we have no access because of the breakdown in relations between the opposition and the government.

“But really, that’s beside the point,” Tayb continues. “We need a system which works and doesn’t need protektziya. Why is there no parliamentary oversight of the Exceptions Committee? How can such a body that makes decisions for so many people be unaccountable to the Knesset?”

But as Israel’s borders slam shut once again, and Ben-Gurion Airport staff prepare to return to the dark days of a closure that may not be lifted so quickly, the only people who matter have decided on a harsh dose of public health medicine.

For hundreds of thousands left on either side of Israel’s sealed borders, Michal Cotler-Wunsh’s comments this week in the Knesset sum up the feeling of reaching a dead end.

“After two years of the pandemic, we cannot go back to square one.”

Waiting for Her Children

She never complained, at least not to me. But Savta wasn’t the complaining sort — she was so full of faith that Hashem has a plan.

I’m lucky enough live in Eretz Yisrael, the place she called home for the last decade of her life. Throughout the past two years, there were ups and downs, periods we could visit her in a chilly courtyard in her assisted-living facility, and times we were barred from entry. My ever-devoted aunt and uncle — the only couple of her five beloved children who live here in Eretz Yisrael — were allowed in the building when the Covid numbers were down. But never were her young great-grandchildren, the little glowing lights of her life, permitted to be brought into the facility.

We stood behind windows waving with signs, my little girls did dances for her behind a glass door. Once I took my children outside the building and stood so far away we had to yell.

Her devoted aide snuck her outside, and I screamed, “Hi, Savta, it’s me, Rachael!”

And she yelled back, in a weak voice, “I would recognize you anywhere, love.”

And for that fleeting moment, there was comfort; we were under the same patch of sky at least.

Before Covid, her ever-loving, ever-devoted children flew in constantly to be at her side, to brighten her spirits while her vision deteriorated in one eye and her 90-plus-year-old body weakened until she could no longer walk, her fingers gnarled until they could no longer sew or create or cook or tidy up.

During Covid, my parents, aunts, and uncles did everything they could to visit. My uncle on this side of the ocean worked hard cutting through seemingly endless red tape on behalf of his siblings, while they all worked on their end in the US. And there were times they could visit. But for the most part, they were barred, their visits relegated to fuzzy Zoom meetings.

I can’t even type these words without crying, thinking that for the most part of the last two years, my regal, wonderful, loving, constantly giving Savta was alone in her apartment with no one but her caring — but not blood-related — foreign aide.

When her health deteriorated to the point that she was on her deathbed, her children were granted permission to come in. But by the time they were cleared to come, her eyes were already closed, and wouldn’t open again — even for her precious children — while she hovered between life and death over the next few weeks. I’d like to think she knew they were there, as she bid farewell to this earth.

Savta had covered her entire apartment, every single inch of wall space, with photos of her offspring over the decade she lived here. I hope those hundreds and hundreds of photos gave her some comfort during the last two years. But at the end of the day, photos are only reminders of the family she created, a pale stand-in for the real thing.

Hashem has a plan, she would say. I know. It’s true. But for now, I grieve. I think it’s less about a life so beautifully lived coming to an end and more about the loneliness she suffered at the end.

For those of us fortunate to live here far away from our closest family, Covid has torn away something invaluable. It’s the weddings, the bar mitzvahs, the life events, the kisses and hugs and nachas and the underestimated but oh-so-powerful warmth of extended family. And I’d venture to say there’s not one of us living here who doesn’t feel it in one way or another.

I understand the decision of our government to enact precautions in the face of a deadly virus, but to what end? I think of Savta, surrounded by two-dimensional photos while waiting fruitlessly to see her children in the flesh, and I wonder: to what end.

—Rachael Lavon

Sky’s the Limit

For the past 30 years, my widowed mother has lived on her own in her beloved Jerusalem. She’d made aliyah a decade earlier with my father, yet after his petirah, she wouldn’t even consider joining any of her children around the world. She was determined to live out her golden years in the Holy Land. Until several years ago, she was completely independent and led a vibrant, active life. She was well into her nineties, but still volunteering, exercising regularly, traveling to visit relatives around the world, and regularly hosting those who came for yeshivah and seminary.

Over the past few years, she’s grown increasingly housebound and dependent on others for her daily functioning, and we children arranged our schedules so that she’d have a visit from one of us each month plus Yamim Tovim. These visits kept her going — but it all ground to a halt in March 2020, when the borders snapped shut and the world hunkered down under the onslaught of Covid. My mother could not understand what was happening — the children scheduled to come for Pesach had to cancel their plans, and her regular visitors were staying away. She was left mostly on her own, save for the few neighbors and relatives who took care of her needs, with all the necessary precautions.

Difficult as this was for her and for us, there was little we could do about it. The virus was raging, people were dying, and we had to sit tight and wait it out — for the next 15 months. As the borders slowly started opening earlier this year, we all made it a priority to do whatever possible to become eligible for entry into Israel: vaccinating, bureaucratic applications, you name it. And gradually, the visits began again — not as frequently as pre-Covid, of course, and planning was always up in the air, but she enjoyed several visits over the summer, and was thrilled to host one of her children for Succos.

I was up to visit next, in early November, and made sure to stay up to date on the constantly changing guidelines. I had a valid green pass from my July visit, based on my recovered/vaccinated status, and booked my flight with confidence. But just days before my scheduled departure, the regulations changed: I was notified that my green pass, and the entry permit that came along with it, was no longer valid, and I needed to have another vaccine in order to be granted entry. But I wasn’t yet eligible for that booster in my home country! And even if my doctor could get authorization, I would still need to wait two weeks after the vaccine.

Around this time, my mother’s health took a drastic turn for the worse, and I frantically reached out to every possible resource for advice. One of my siblings was able to gain entry during this time and rearranged her schedule to travel, so I got the second vaccine and booked tickets for early December.

And then — Israel closed the skies to non-citizens days before my scheduled flight. I felt utterly trapped between increasingly worrying updates from Israel and an intransigent system that kept pulling my access to my mother just beyond my grasp.

When I turned to Chaim v’Chessed for information, they were so gracious and helpful, but also quite frank: With all due respect to a 98-year-old with failing health, there was no specific crisis designating this as a “medical emergency” that would qualify me for an entry permit. (In fact, I was told, it would be easier to arrange entry in the case of a levayah, chas v’shalom. Apparently, they told me, the committee feels that the chutznikim want to have everything their way, even though the country has every right to make the laws that they deem safe for their citizens. I’m all for safety precautions, but it’s hard for me to believe that a recovered-and-vaccinated non-citizen will pose more of a threat than the Miss Universe candidates.) Still, they took on my case for a “charig” request. Two harrowing days later — during which time my mother’s condition continued to spiral downward — the organization actually came through with an “ishur charig” — that coveted special entry permit. Bless them!

I got on a flight hours after receiving the blessed permit, and not a moment too soon. My visit is a rotation of doctors, nurses, and remote-ER medical testing, coming through the door of my mother’s house. Meanwhile, I’m davening this doesn’t escalate into the “emergency” that the vaadah demands.

—Dina Silverstein

A World Away

I live in Israel with my husband and seven children. We all hold student visas, which didn’t affect us much. Then Covid struck. We realized that we wouldn’t be able to see our extended family for a while. We learned what it’s like to make a bar mitzvah without grandparents or close relatives in attendance. But we didn’t realize that the government’s Covid policies would actually separate me from my own children.

Last year, my parents, who live in Belgium, fell ill with Covid. Three weeks later, they had recovered but still felt very weak. I decided it was high time I visit them. I packed up my eight-month-old baby and left the other children in my husband’s care. The plan was for me to stay from Thursday till Tuesday; after all, there was no way I could leave my kids for longer than that.

On Sunday, while I was in Belgium, the news came — within 24 hours, Israel was closing its borders indefinitely. Since I’m not a citizen, I would not be allowed back in.

My husband scrambled to get me an “ishur” — the necessary approval to return — but by the time it arrived, I no longer had any flight options.

There I was, a mother of small children, the oldest just 13, stuck in a different country, on a different continent, with no way to return to my family. Every day my husband tried some other way — more phone calls, more pleading — to no avail.

Days passed. Weeks passed. And I was still separated from my family by a government that couldn’t or wouldn’t provide the requisite approval for a mother to return home.

Finally, after three desperate and fruitless weeks had passed, my husband heard of a “rescue flight” leaving Frankfurt. I needed a special ishur from an exemption committee to board that flight, but the committee seemed to be nonexistent because despite all my husband’s efforts, there was no one to talk to. Finally, my husband was put in touch with the deputy transportation minister, who emailed him the precious ishur.

I traveled four hours to Frankfurt by taxi (400 euros, no flights available). After I checked in, I was told to my utter dismay that my ishur had been revoked because I wasn’t an Israeli citizen. I left my parents’ home at 8 a.m. and arrived back at their doorstep at 9 p.m. that evening, exhausted, disappointed, and longing to be elsewhere.

After about a zillion emails, phone calls, help from Chaim V’Chessed and about 100 other askanim, including a proffered (though declined) interview from Radio Kol Chai to publicize my plight, somebody connected me to the boss of Israir Airlines, who personally assured me I’d make it on the following week’s rescue flight from Frankfurt.

The long-awaited day arrived. After a four-hour delay in the airport, I was finally, finally sitting on the plane winging its way back to my family. After we disembarked and got through passport control, border police surrounded us on all sides and informed us we were to board buses for a two-week stay at a quarantine hotel. This was too much to bear. How long could I be separated from my children?

I sat down on the floor and said, “I had Covid, for goodness’ sake! I have antibodies! I’m not going anywhere but home!” and to everybody’s surprise, including myself, vomited.

“Kulam osim oto hatzagah [Everybody puts on the same performance],” one of the soldiers callously mocked me.

I phoned up my husband in tears.

“Ask for Mrs. So and So!” he told me.

I don’t remember her name — in my mind she will always be Mrs. Eliyahu Hanavi. She turned up and said the magic words — “What’s the problem? She can quarantine at home.”

I was handed a red paper wristband that would allow me exit from the terminal.

When I got to the exit, I showed the guard my wristband, impatient to make that final sprint out of the terminal doors and into the fresh winter Tel Aviv air.

“Just a minute,” he said, and searched my baby’s hand for her wristband. “Geveret, your baby can’t leave the terminal without a wristband. She needs to be quarantined at the hotel…”

I took my baby out of her Doona, plunked her into his hands and said, “I need to see my other children! You can watch her in the hotel for two weeks!”

Then, coming to my senses, I insisted that he summon my savior, Mrs. E. Navi. Once again, she came to the rescue and allowed me to leave together with my baby, with strict instructions that we quarantine at home.

She needn’t have worried. I was so thrilled to be back home, I was more than happy to stay put for as long as her heart desired.

—As told to P. Diamond

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 891)

Oops! We could not locate your form.