Canceling the Calendar

| September 13, 2022In the 1920s, a novel proposal known as the International Fixed Calendar threatened to upend Jewish tradition

Title: Canceling the Calendar

Location: Washington, D.C.

Document: Jewish Telegraphic Agency

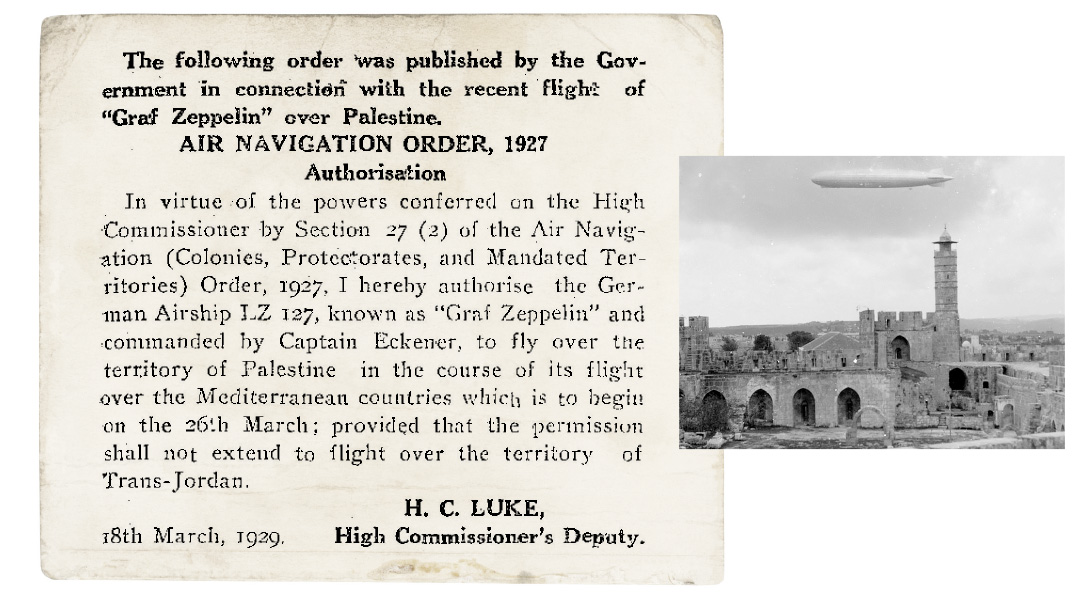

Time: 1929

Jewish observance has always revolved around the calendar. Though the Jewish year follows a combined lunar-solar calendar, the Gregorian calendar, which tracks the solar year on a seven-day week, is significant in Jewish life as well.

In the 1920s, a novel proposal known as the International Fixed Calendar threatened to upend Jewish tradition. A British accountant named Moses Cotworth found that monthly accounting was greatly complicated by the fact that months did not divide evenly into weeks, and he devised a solar calendar of 364 days, divided into 13 months of 28 days each. Each month would be exactly four weeks. Each date of the month would fall on the same weekday every month, and every year would have exactly 52 weeks.

In addition to the simplicity this would create for scheduling, this new calendar would be of great benefit to the business world, which would now have four equal-length quarters of 91 days, 13 weeks, or 3.25 months long. The proposal had benefits for general society as well. Because this was a perennial calendar, movable holidays such as Thanksgiving Day could now have a fixed date while keeping their traditional weekday.

The calendar proposal gained traction in 1924, due to the advocacy of George Eastman, founder of the Eastman Kodak Company. For observant Jews across the world, this proposal caused alarm. The new calendar’s structure of 13 months of 28 days each resulted in 364 days. The solar year lasts 365 days; to bring the calendar into balance, an extra day, dubbed “Year Day,” would be added. This holiday would not be assigned to a specific day of the week. If the day preceding Year Day was Saturday, Year Day would not itself be called Sunday, but rather would be followed the next day by Sunday. For Jews, this would necessitate that Shabbos be observed on a different weekday every year.

As the League of Nations and US Congress debated the measure, American Jewry united and created the League for Safeguarding the Fixity of the Sabbath, which urged American Jewry to petition Congress against destroying the fixity of the Holy Days.

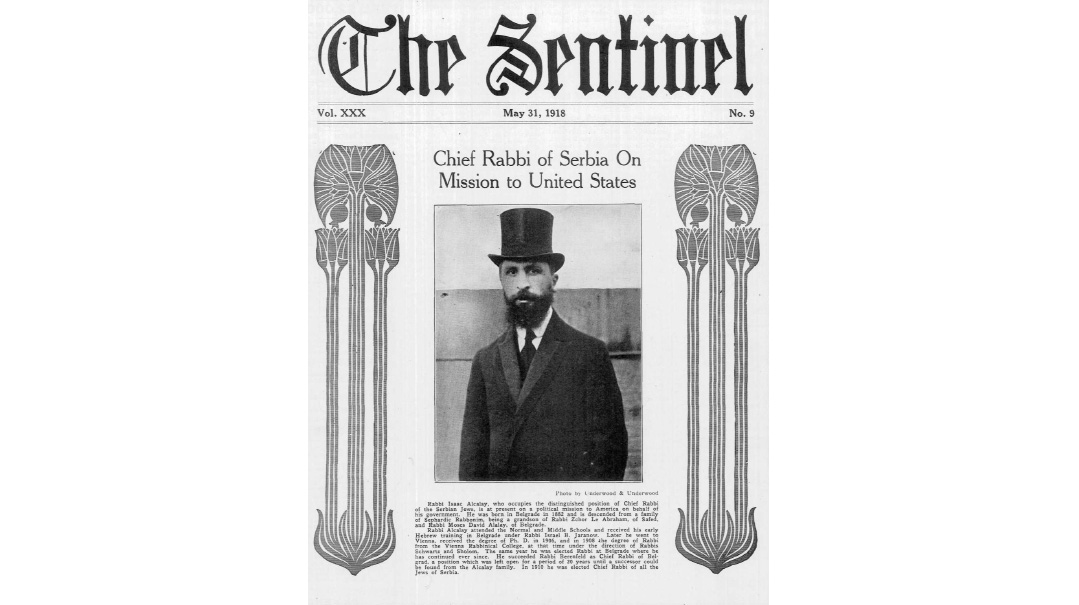

The group found its savior in New York’s Congressman Sol Bloom. While Bloom was a secular Jew who was hardly renowned for his defense of Jewish causes (especially his support for Roosevelt administration policies during the Holocaust), he declared this proposal an attack on “all organized religion,” and accused its propagators of “putting business before G-d,” deeming it a violation of the First Amendment.

Bloom also argued that the addition of a 13th month would mean that tenants needed to pay an additional month’s rent, while employers would be slow to raise salaries. If the issues at stake were primarily business concerns, then businesses were free to use simplified calendars internally on their own volition.

“I sincerely believe that every businessman can utilize the 13-month plan without making it necessary to have Congress... foist this new scheme on an unwilling and unprepared world,” Bloom said.

Bloom’s battle thwarted Eastman’s quest to get the bill passed in Congress, and the League of Nations soon abandoned it as well. Bloom later related in his memoirs, “Ordinarily I would have been completely satisfied with the quiet demise of a bill I had opposed, but in this case I wanted a state funeral — so that a permanent monument would be erected to warn future calendar reformers.”

More Than a Kodak Moment

While George Eastman made his mark on the world as the man responsible for bringing the photographic use of roll film into the mainstream, he devoted his final years to trying to bring his calendar proposal to fruition, spending a small fortune to push the plan in any way possible, even creating new publications that propagated the plan’s virtues. Incredibly, the Kodak Company, which adopted the use of the 13-month-calendar in 1928, didn’t abandon its use until 1989.

Calendar Revolution

The early Romans instituted an eight-day week, which included a day of the week designated for shopping. During the French Revolution, efforts were made by the Jacobins to rid society of all royalist and religious influences. The Gregorian calendar was discarded in 1793 and replaced with a new one containing 12 months, each containing three weeks of ten days, with complementary days added to complete the solar year. Each day was divided into ten hours, an hour was 100 minutes, and each decimal minute into 100 seconds. The calendar lasted slightly more than a decade, but seeing how the confusion it generated hurt trade opportunities with neighboring countries, Napoleon abolished the revolutionary calendar in 1905.

Works by Elliot Resnick, Rabbi Dr. Sidney Hoenig, and the Kodak Archives were referenced in the production of this article.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 928)

Oops! We could not locate your form.