Between the Lines

Scientists know how to teach kids to read. But are our schools using their methods?

T

zippy remembers exactly when she realized Chaim was going to struggle with reading. They were sitting at the kitchen table, a worksheet in front of them. Chaim was supposed to identify the letters of the alphabet and their accompanying sounds.

“He got maybe 20 percent of it right,” Tzippy recalls.

She brushed her concerns aside. After all, he was only in kindergarten, and the school year had just begun. But the year progressed, and he made little progress. Then Covid hit. Chaim’s school closed and shifted to remote learning.

“Chaim’s reading got worse,” Tzippy says, “but I thought it was because he was learning over Zoom.”

Tzippy assumed Chaim’s reading would pick up once he was back in the classroom, but as a precaution, she arranged for him to be in a smaller class for first grade.

Initially, things seemed to improve. Chaim was finally able to make sense of letters and sounds, and he’d bring home books to read aloud for homework. While his reading was halting and reluctant, Tzippy focused on his improvement from the year before.

Then, one afternoon, Chaim had a friend over, and Tzippy overheard him reading.

“His friend flew through the words,” she remembers. “And it was a book I never imagined could be at Chaim’s grade level.”

She felt unease deep in the pit of her stomach and called Chaim’s teacher. The teacher wasn’t worried, though.

“Just practice,” she said. “Every child learns at his own pace.”

The teacher explained to Tzippy how she tracked the students’ progress: The students were separated into groups in which they read at their own levels, starting from A and progressing to G. Now Tzippy had a way to gauge Chaim’s progress — and she was very disturbed by what she discovered.

“He was stalled at the same level all year,” Tzippy says.

Tzippy started practicing reading with Chaim every night, but nothing changed. His reading was painful to listen to — he stumbled over the words and read with little expression — and his frustration was rising. Sometimes he refused to do his homework.

Tzippy consulted with the teacher several more times throughout the year. Each time, she got the same response: “Just be patient,” she’d tell her. “It takes some kids longer to catch on.”

By this point, Tzippy decided it was time to seek answers outside of school. She called Malky, her childhood friend who still lived back home in New York and was now a reading specialist.

Malky listened to Tzippy’s description of Chaim’s reading issues, then told her that maybe Chaim needed to learn to read a different way.

“Use the Orton-Gillingham Method,” she advised.

Tzippy had no idea what that was, but she assumed Chaim’s teacher would know. However, when she asked her about it, his teacher had never heard of it either.

The Reading Wars

English is a complicated language to decode, and there’s always been debate about the best way to teach children to read. Over the years, the two primary methods, phonics and whole language, have waxed and waned in popularity.

Phonics advocates teaching the relationship between letters and sounds and encourages readers to sound out unfamiliar words.

Whole language, which became popular in the 1980s, teaches kids to read by recognizing words as whole pieces of language. This approach is based on the belief that children learn to read using visual memory. If students are exposed to a word enough times, they learn to store the word as a picture in their brain, and recognize it when it appears in a text.

In the whole language approach, teachers rely on the three-cueing method to help budding readers identify unfamiliar words. Readers are encouraged to read an unfamiliar word using one of three prompts: context of surrounding text or accompanying pictures, sentence context (what word would make sense here), and visual information, which means using the letters within the word as hints to guess what the word might be.

When teachers began to notice that many children had trouble decoding words using whole language, they added phonics back into the curriculum. This combination of both approaches, called balanced literacy, advised that phonics be used when the three cues failed to produce desired results. Today, a large number of schools use a balanced literacy reading curriculum. Its supporters claim it allows children to interact with language naturally, that we’re all born with the ability to read much in the same way, that we’re all born with the ability to speak, and that teachers only need to activate the ability.

The Science of Reading

As whole language became the darling of school curriculums across the country, cognitive scientists were making great strides in understanding how our brains decode words — and their findings were in direct opposition to the basic premises underlying whole language and balanced literacy.

Over the last five decades, scientists across the world and across multiple disciplines, including cognitive and developmental psychologists, neuroscientists, and linguistics experts, have performed extensive research on reading and reading-related issues. Their collection of findings, coined the science of reading, offers insight as to why some children face difficulty when they learn to read, and outlines steps that could improve student outcome and prevent difficulties from developing in the first place.

One of the most interesting takeaways from this body of research is that all children — including children with dyslexia — learn to read the same way: by making the connections between sounds and words and the letters that represent those sounds on the page.

“We teach reading in different ways; they learn to read proficiently in only one way,” says David Kilpatrick, professor of psychology at New York College and author of Equipped for Reading Success.

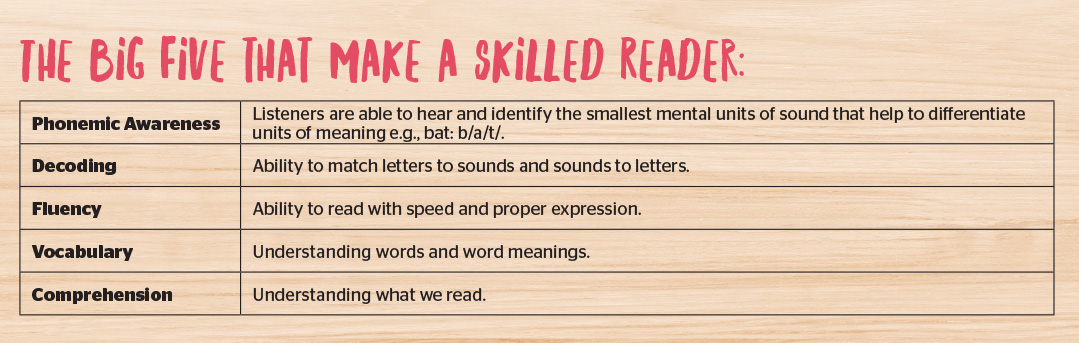

In 1997, Congress established the National Reading Panel to investigate this collection of findings. Their conclusions, issued in 2000, stated that good readers need what is known as the Big Five: phonemic awareness, decoding, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. This approach is called structured literacy.

Outside Help

On a hot summer day, with golden sunshine and temperatures in the high eighties, Tzippy gathered pool toys into a tote, while her children waited impatiently at the door. They were off to the pool.

All except Chaim. He had a tutoring session.

As first grade drew to a close, and Chaim’s reading lagged well below grade level, his teacher finally conceded he needed extra help. The school referred them to a teacher who worked in the school’s resource room, and suggested they use the summer months to help Chaim improve his reading.

Chaim was not happy about the arrangement.

“He was missing so much summer downtime,” Tzippy remembers. “He just wanted to go out and play, and instead, he was cooped up with a tutor.”

Still, it seemed a worthwhile investment of time — reading is crucial for success in school — and she encouraged Chaim, telling him that the upcoming school year would be much easier for him if he’d just work with his tutor.

When chatting with Malky, Tzippy mentioned that the school suggested a tutor for Chaim.

“Make sure she has the proper training,” Malky told her.

Tzippy was unconcerned. “Of course she has proper training — the school recommended her!”

Then summer ended. After their final session, when she reviewed their work, the tutor admitted that she’d seen little improvement.

Tzippy was devastated.

“I cried,” she says. “All I could think of was how hard Chaim had worked, and how much money we invested, and in the end, there was nothing to show for it.”

At a loss, she called the director of school’s resource room.

“Maybe try Orton,” the director told her, echoing Malky’s words from months before.

Tzippy still didn’t know what Orton was, but she was open to learning. She finally realized that Chaim’s tutor had been using the same method his teacher used in the classroom. It wasn’t surprising she’d gotten the same dismal results.

Phonics Matters

Supporters of balanced literacy say their approach fosters a love of language and reading. They admit phonics are necessary for reading, but they resist phonics drilling, saying that rote learning doesn’t create lifelong readers.

But studies have shown that by teaching the three-cueing system to new readers, educators were actually creating poorer readers. When children use a picture or guess when they come to a difficult word, it shifts their focus away from the word itself, decreasing the chances they’ll recognize the word the next time they see it.

Also of concern is balanced literacy’s lack of attention to phonics. Balanced literacy doesn’t ignore phonics, but uses it as a remedy when a child seems unable to read a word. If a teacher sees the three-cueing method doesn’t work, she’ll encourage the child to “sound out” the word.

But decades of study show that phonemic awareness and decoding are integral in learning to read; phonics should be foundational, not a backup option.

Another problem is the insistence of whole language proponents that reading is an innate ability much as speaking. This attitude gives rise to the “wait-and-see” model.

In reality, though, reading is a skill that needs to be taught. Waiting to intervene creates a larger problem. It’s harder for kids to pick up reading at a later age, the methods become less effective, and many children will have developed additional problems such as anxiety and self-esteem issues. Reading researcher Keith Stanovich points out that with the whole language model, the rich get richer, the poor get poorer — i.e., those who start reading well continue to do so, while those who don’t are unlikely to catch up. Children who lag may develop many secondary learning issues such as less exposure to background knowledge, less-developed vocabulary, more limited comprehension strategies, and poorer writing skills.

As a reading specialist, Malky was aware of balanced literacy’s pitfalls. The Orton-Gillingham method she recommended to Tzippy eschews the three-cueing method. It’s a multisensory approach, built upon previous lessons, and heavily focused on phonemic awareness.

It’s All About Structure

Sara Gross, founder of ReadBright, is a reading consultant in Lakewood, New Jersey, with over 30 years of experience and clients across the country. She has seen many schools switch their reading programs to a structured literacy program or add it to existing programs.

Forty years of extensive research supports the switch, she says. She also notes that one of the leaders of balanced literacy, Lucy Calkins, has added phonics back into her curriculum. (Lucy Calkins made the phonics adjustment after numerous states banned balanced literacy curriculums.) Sara Gross’s own experience in the field backs this up.

“I tried every approach over the years,” Sara says. “The best way to teach children to read is with systematic, explicit phonics instruction.”

Balanced literacy emphasizes comprehension first, she says, but children need to learn to decode first, and comprehension can be tackled through teacher read-aloud selections. For teachers, balanced literacy may be more exciting to teach, but statistics show it isn’t effective across the classroom.

“In any class, 30 percent of students will grasp reading no matter which method is taught,” says Sara. “However, when balanced literacy is the teaching method, many students will need additional instruction. Seventy percent of students will benefit from structured literacy.”

Louisa Moats, who is at the forefront of reading research and author of many books on literacy instruction, puts that number even higher. In a now-famous article, “Reading Is Not Rocket Science,” she says that with structured literacy, “ninety five percent of children can be taught to read by the end of first grade.”

That isn’t to say that structured literacy is a panacea. In any class, a possible 15 to 20 percent of children will need more direct instruction, but those students likely have additional learning differences. “We shouldn’t blame the teacher or the program,” Sara says. “There are always children who will need direct and more specialized instruction.”

However, when in a balanced literacy curriculum, there will be more children who will need additional instruction, she says, while structured literacy will help most students.

“Not every child needs structured literacy,” she says, “but it will help the largest number of students.”

Esther Baila Merenstein is a reading specialist from Waterbury with 20 years of experience as a first-grade teacher. She decided to become a reading specialist when a close family member was struggling with reading, and she took a six-month course with the Dyslexia Institute. She calls Orton-Gillingham her playground.

Esther Baila believes that much of the difficulty frum kids experience with learning to read is based on the way our school systems are set up.

“Our yeshivos are doing the best they can,” she says. “When there’s Hebrew in the morning and English in the afternoon, children are being presented with a lot of material at once. When the focus is on everything at once, children won’t become proficient readers.

“A significant portion of children will learn how to read through balanced literacy, through exposure. But that doesn’t mean I’m a fan of it,” Esther Baila says. She explains that children still need a structured literacy program to help them advance their reading skills and become proficient readers. “However, since many kids will learn regardless of the method, why shouldn’t we gear the classroom setting toward the kids who need it, to give them a leg up? Everybody benefits from a structured program. Every good Orton-Gillingham-based curriculum has a great fluency component, a rich vocabulary component, a great comprehension program. Why go with the balanced literacy? For who? For kids who will learn how to read anyway? They’ll learn through a structured program just as well, get everything they need, and this way, you help the kids who really need it.”

Still, she cautions, there will always be children who struggle.

“Sometimes children who have a reading issue also struggle for variety of reasons — dyslexia, an auditory processing disorder, ADHD,” Esther Baila says. “A combination of any two makes it even more challenging.”

Those children will need more intense instruction, either increasing the time spent on reading, varying the modalities, or reducing student-teacher ratio, as well as a structured literacy program like Orton-Gillingham.

Esther Baila also points out that the bulk of formal reading instruction ends in second grade, when the curriculum shifts from learning to read to reading to learn. Some children need reading instruction for longer.

Red Flags

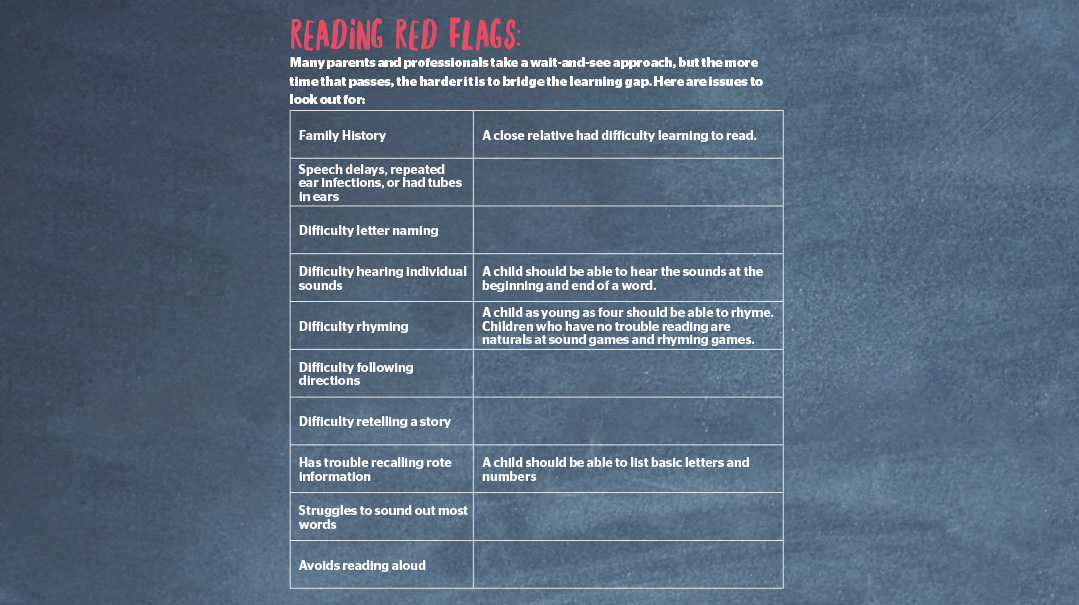

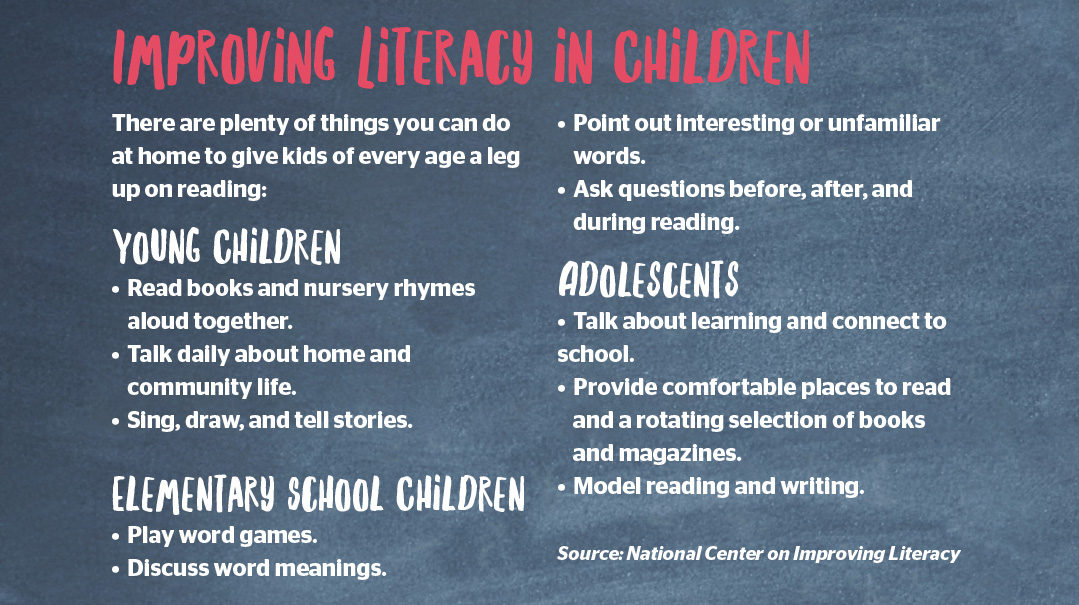

It’s never too early to address a reading problem, especially because the more time passes, the harder it is to close the learning gap. In larger classes, teachers may not pick up on a child’s reading difficulties right away, so it’s important for parents to be on the lookout, even as early as kindergarten, when alef-beis instruction and kriah begin, for any potential red flags (see sidebar).

Meanwhile, the science of reading is making its way into the classroom. Many states have issued legislation mandating schools return to a phonics-based approach to literacy. In New York City, Eric Adams (who struggled with undiagnosed dyslexia as a student) unveiled a plan to turn around the literacy crisis in New York.

But shifting reading curriculums to structured literacy, while helpful, will not be fully effective without adequate teacher training. Most teachers are likely to revert to the methods they’re familiar with. The reading debate is also contentious, and many educators are devoted to either one method or the other.

Still, an honest look at recent data is sobering — only 37 percent of high school seniors are proficient in reading — and may provide the impetus to switch to the program borne out by decades of research.

Chaim finally got the help he needed at the start of second grade. He’s been seeing a private tutor who uses the Orton-Gillingham program, and Tzippy says it seems to be working.

“He’s never been officially diagnosed, but he has learning issues,” she says. “He still struggles. He can’t read instructions for games, and I have to sit and help him through it. Reading is so hard for him.”

Looking back, she questions her experience.

“How could the staff not have been trained to recognize a problem and guide me?” she asks.

At the same time, she acknowledges that some parents resist when educators call to discuss a child’s potential learning issues.

“Either way, we lose,” she said.

Tzippy is grateful that Chaim is finally making progress, but pained by how much time it took them to get there. “We could have spared Chaim so much time and frustration if only we’d gotten the right help sooner.”

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 808)

Oops! We could not locate your form.